Surveys show household inflation expectations are less stable than we thought

Prices reflect what people expect them to be—at least in part. That’s why monetary authorities watch inflation expectations closely. They affect people’s behavior in the present.

However, very little is understood about how people form expectations. Central banks typically focus on professional forecasters and financial markets, not households, because economists tend to assume that the inflation expectations of households are well anchored (they don’t change in response to short-term developments). Yet, when we asked 25,000 Americans in 2018 what they thought the average inflation rate in the US was, fewer than 20 percent of survey participants answered, “about 2 percent.” Almost 40 percent reported a number higher than 10 percent (Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Weber 2022).

Not only do most households not have well-anchored expectations, they also tend to overestimate future inflation. Using data from the New York Federal Reserve survey of consumer expectations we find that between 2011 and 2018 men on average expected inflation to rise to about 4 percent over 12 months, while women expected a rate of 6 percent (a difference that holds regardless of financial literacy). Inflation in fact averaged below 2 percent (D’Acunto, Malmendier, and Weber 2021).

This suggests there might be a “gender gap” in inflation expectations. We spoke to both male and female household heads who record their grocery purchases to confirm whether that’s the case. On average, women expect higher inflation than men, but that holds only for “traditional households,” where women do all the grocery shopping. In families where the male household head occasionally shops, the gap disappears.

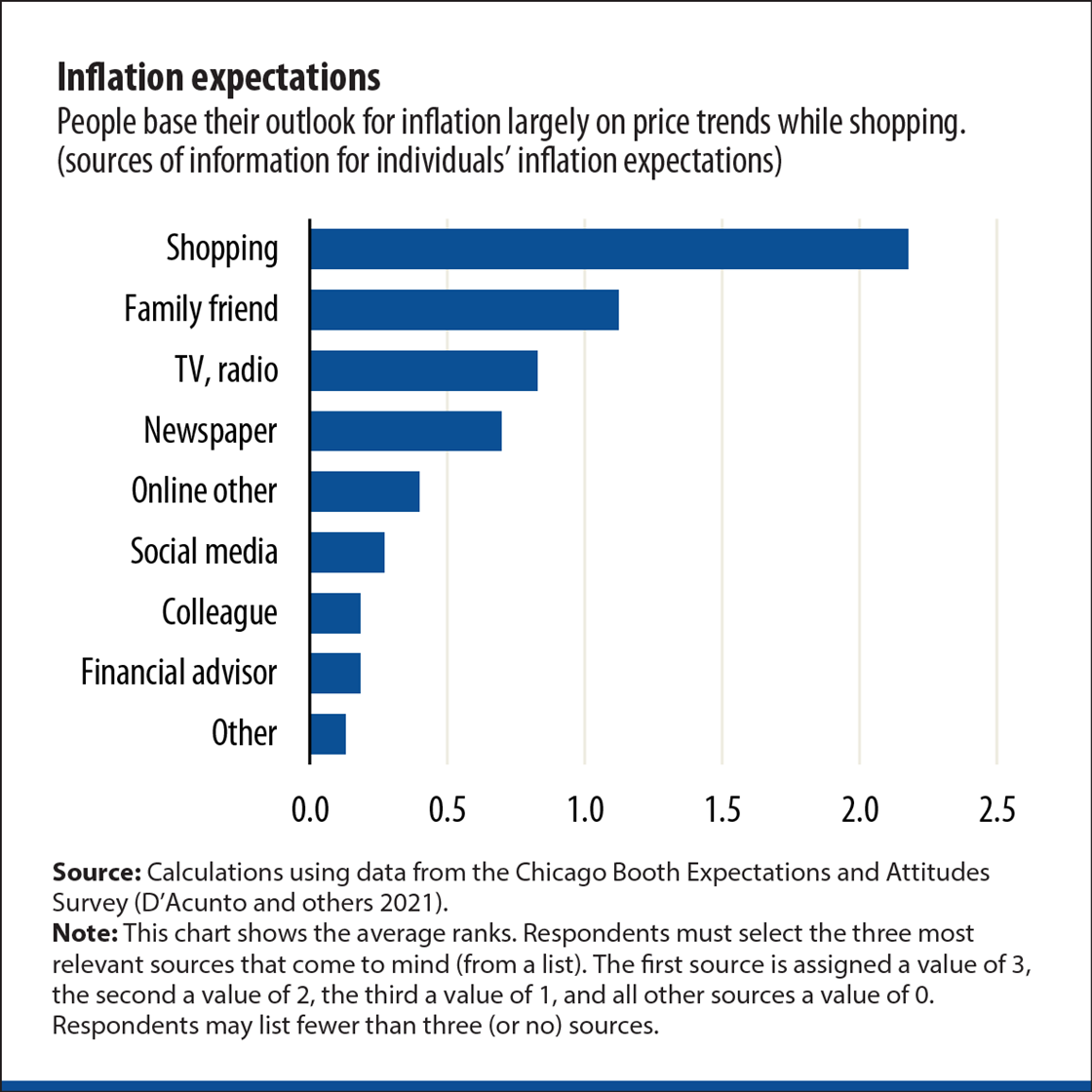

To better understand how exposure to price changes shapes expectations, we fielded another survey in which we asked participants directly which sources of information were most important to them when gauging inflation (D’Acunto and others 2021). It turns out that households rank grocery shopping as the most relevant source of information.

To test this further, we leveraged data from the 50,000 households that participate in the NielsenIQ Homescan panel. With information on what families buy, where they shop, and what they pay, we crafted a household-specific price index and found that families hit hardest by inflation expected an inflation rate 0.7 percentage point higher than other households, on average.

Not all price changes matter equally, however. If they occur in categories that are important to, or used more regularly by consumers—such as milk and eggs—we see immediate increases in overall inflation expectations, both in times of low and high inflation. Households also tend to pay more attention to price hikes than cuts. These factors explain why families updated their inflation expectations in the summer of 2021, when most central banks continued to preach the gospel of temporary inflationary pressures—prices rose in the categories consumers cared about most. More important, these findings imply that even if central banks were successful in curbing inflation in the near term, household inflation expectations would take time to come back down.

Keep it simple

There’s another factor that contributes to household inflation expectations: messaging. More complex policies are more difficult to explain and therefore less likely to shape expectations. In D’Acunto and others (2020), we compare the impact of preannounced future consumption tax increases with forward guidance (a statement that signals the likely future path of monetary policy). Through the lens of the New Keynesian model, both policies should have the same effect on inflation expectations. But they differ quite substantially in their complexity and required understanding of economics.

Data confirms this. Using the German version of the European Commission consumer survey, we find that Germans altered their inflation expectations and spending plans only after the November 2005 announcement by then-Chancellor Angela Merkel that consumption taxes would increase by 3 percentage points in January 2007. By contrast, the announcement in the summer of 2013 by then-European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi that interest rates would stay at current levels or fall (the first time the ECB explicitly used forward guidance as a policy tool) had no impact at all on household inflation expectations or spending patterns in Germany.

Given these findings, we conducted a series of surveys on how central banks could communicate more effectively. For example, we asked thousands of individuals in Finland (D’Acunto and others 2020) questions about their income change expectations and sociodemographic characteristics and then split the sample into three groups: a control group that did not receive any additional information and two treatment groups. We gave these groups truthful information about policy actions taken by the ECB in the spring of 2020, using tweets from the official Twitter account of Olli Rehn, governor of the Finnish central bank. But the content varied between groups. One group received a “target” communication, that is, a message that specifies the aim of a policy without detailing which measures the central bank would implement to achieve it. Another group received information about the “instrument,” the specific policy that was implemented to achieve the goal. All survey participants were again asked the same questions. Our results show that only the target communication effectively improves individuals’ income expectations.

In Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Weber (2022), we focus on the medium of the message. We find that using simple terms like “current inflation,” the “inflation target,” or “inflation forecast” is most effective in managing individuals’ inflation expectations. But the source matters. Newspaper coverage of the Federal Reserve, though simpler to read, has less impact on expectations than official Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) statements. This is because of how households in the US rate the credibility of different news sources. When it comes to information about the economy, newspapers on average rank low, whereas social media and Twitter rank high. These findings suggest that central banks cannot rely on the media alone to transmit monetary policy announcements to households.

The identity of the sender of the message also influences the effectiveness of monetary policy communications. In D’Acunto, Fuster, and Weber (2021), we find that even when the message and forecasts remain constant, women and Black survey respondents are substantially more likely to revise their expectations when the message comes from either Mary Daly or Raphael Bostic, a female and a Black male regional Fed president, rather than from Thomas Barkin, a white male regional Fed president. Emphasis on the female or Black male presence on the FOMC increases women and Black survey participants’ trust in the Federal Reserve and piques their desire for information about monetary policy.

Taking stock

Taken together, these results show that individuals in general do not have well-anchored inflation expectations. People focus on the price changes of relevant individual goods and pay more attention to price increases than cuts.

Central banks could manage the expectations of households if they use simple messages. But the medium that transmits the message and the identity of the messenger matter. Reaching ordinary families, which typically do not follow official releases, remains the biggest challenge for central banks. Creative and clear communications could fill the gap.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Coibion, Olivier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Michael Weber. 2022. “Monetary Policy Communications and their Effects on Household Inflation Expectations.” Journal of Political Economy 130 (6): 1537–584.

D’Acunto, Francesco, Daniel Hoang, Maritta Paloviita, and Michael Weber. 2020. “Effective Policy Communication: Targets versus Instruments.” BFI Working Paper, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, University of Chicago.

D’Acunto, Francesco, Ulrike Malmendier, and Michael Weber. 2021. “Gender Roles Produce Divergent Economic Expectations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (21): 1–10.

D’Acunto, Francesco, Ulrike Malmendier, Juan Ospina, and Michael Weber. 2021. “Exposure to Grocery Prices and Inflation Expectations.” Journal of Political Economy 129 (5): 1615–639.

D’Acunto, Francesco, Andreas Fuster, and Michael Weber. 2021. “Diverse Policy Committees Can Reach Underrepresented Groups.” BFI Working Paper, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, University of Chicago.