Building Bridges to Future Growth

October 5, 2023

As prepared for delivery

Your Excellency, Monsieur le Président Alassane Ouattara,

Monsieur Adama Coulibaly,

Ministers,

Members of Parliament,

Members of the diplomatic community,

Leaders of international organizations,

Honorable guests,

Mesdames et messieurs, good afternoon and thank you for your warm welcome here in Abidjan.

Earlier today, I had the opportunity to cross the beautiful Alassane Ouattara Bridge. This new transport connection is not just critical for this city. It symbolizes the transformation of Côte D’Ivoire—from a conflict-affected and fragile economy more than a decade ago to one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa. We need this spirit of optimism everywhere!

I am here because of another important connection—between Africa and the IMF.

Next week our Annual Meetings will be held in Marrakech, bringing together finance ministers and central bank governors from 190 countries. They will mark an important anniversary: half a century since the Meetings were last held in Africa—in Nairobi in 1973. Just weeks after a terrible earthquake, Morocco will bring the international community together in a spirit of solidarity and commitment to overcome the challenges we face. I want to express my heartfelt sympathy to the Moroccan people and my gratitude for generously hosting our meetings.

In the fifty years since our last meetings in Africa, the world has transformed in so many ways—life expectancy is up, globally poverty has declined, the international monetary system has adapted to a flexible exchange-rate regime, and technology has transformed the way we work, entertain and communicate. But inequalities within and across countries have increased and we are facing an existential climate crisis. And growth has been on a declining path over the last decade.

This demands actions to pave the way to the next 50 years. Our goal must be to build bridges to strong future growth that is both sustainable and inclusive.

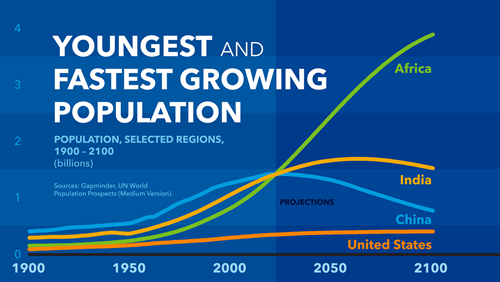

This will be the focus of my remarks today. Being here, in Abidjan, on African soil, I take inspiration from Africa. On this continent we can see, as under a magnifying glass, the challenges facing the world. But we also see its great potential. Africa has abundant resources, and boundless creativity and energy. And it is home to the world’s youngest and fastest-growing population .

To put it simply, a prosperous world economy in the 21st century requires a prosperous Africa. Advanced economies are rapidly ageing, but they have abundant capital. The key will be to better connect that capital to Africa’s abundant human resources—to inject more dynamism into the current anemic global growth outlook.

Africa also makes the strongest case for building economic resilience. The COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine, climate disasters, the cost-of-living crisis, political instability: these are the many faces of a shock-prone world. Their impact is most fully on display in Africa, as is the overwhelming necessity to better prepare ourselves for that world.

And a prosperous Africa requires maintaining the most important bridge of all, the bridge that connects all countries—that of international cooperation.

As people in Abidjan would say: “On est ensemble”—“We are together”. During the meetings we will make coming together meaningful for the people in our member countries.

Global Outlook: The Economy Is Resilient, But Challenged By Weak Growth and Deepening Divergence

Let us start with the economic outlook. The world economy has shown remarkable resilience, and the first half of 2023 has brought some good news, largely because of stronger-than-expected demand for services and tangible progress in the fight against inflation.

This increases the chances for a soft landing for the global economy. But we can’t let our guard down.

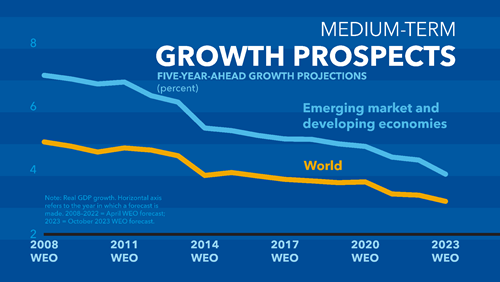

While the recovery from the shocks of the past few years continues, it is slow and uneven. As you will see from our updated forecast next week, the current pace of global growth remains quite weak, well below the 3.8 percent average in the two decades before the pandemic. And looking ahead over the medium term, growth prospects have weakened further.

Yet, there are stark differences in growth dynamics. Stronger momentum comes from the United States. India and several other emerging economies, including Côte d’Ivoire, are bright spots. But most advanced economies are slowing down. And in China economic activity is below expectation, and many countries struggle with anemic growth. Economic fragmentation threatens to further undermine growth prospects, especially for emerging and developing economies, including right here in Africa.

This results in deepening divergence in economic fortunes between and within different country groups. Part of it comes from “economic scarring”. We estimate that the cumulative global output loss from successive shocks since 2020 amounts to $3.6 trillion as of 2023.

This loss is unevenly distributed across countries. The U.S. is the only major economy where output has returned to its pre-pandemic path. The rest of the world is still below trend, with low-income countries being hit the hardest. Why? Because they have had extremely limited capacity to buffer their economies and support the most vulnerable.

Divergence is also driven by differences in policy space and macroeconomic fundamentals, in the extent of dependency on fuel and food imports, in the share of goods versus services in the economy, the role of trade, reform momentum, and the pace of the fight against inflation—all those affect both countries’ policy choices and their economic performance. What this leads to is countries increasingly marching to their own tune.

Policies for Stronger Future Growth

Given these diverging trends, the Fund has an important role to play to help countries identify policy choices and pursue successful growth strategies. Three policy priorities stand out.

First, reinforce economic and financial stability.

Fighting inflation is the number one priority. Thanks to the decisive actions of central banks and responsible fiscal policies inflation in most countries is going down, but is likely to remain above target, for some countries all the way until 2025. High inflation undermines consumer and investor confidence, erodes the foundation for growth, and above all hurts the poorest people in society the most.

Winning the fight against inflation requires interest rates to remain higher for longer. It is paramount to avoid a premature easing of policy, given the risk of resurging inflation. New IMF analysis shows the growing importance of inflation expectations as a driver for price increases. [i] To help shape people’s views of inflation, policymakers need to clearly communicate their goals.

They also need to safeguard financial stability. Expectations of a “soft landing” helped boost various asset prices. But a rapid reassessment of this outlook—with inflation suddenly resurging—could lead to a sharp tightening of financial conditions, hitting markets and economies hard.

Tighter credit is already putting pressure on many borrowers, such as commercial real estate firms in the U.S. and Europe. In China, continued stress in the property sector is a cause for concern. So, too, is high leverage in parts of the non-bank sector.

Banks are also facing pressures, as you will see in the Global Financial Stability Report next week. [ii]

And we now face significant risks on the fiscal side. To prepare for tomorrow’s shocks and make vital investments, countries must rebuild their budgetary room for maneuver. In most cases, this means tighter fiscal policy—which can also support monetary policy where inflation pressures are still strong.

The stakes are high, because the shocks of the past few years have caused a further rise in debt burdens in many countries, including in Africa. With little or no fiscal space left—and with rising debt servicing costs—many governments are facing tough decisions. It means prioritizing spending and communicating clear medium-term fiscal plans to build credibility and reduce debt levels.

Some countries in Africa are reforming their energy subsidies to create space for development spending. Nigeria, for example, recently removed fuel subsidies that cost about $10 billion last year—four times the amount spent on health.

Many countries also need to generate higher and more reliable domestic revenue. This is an area where the IMF has supported about 150member countries over the past two years alone—helping to improve the design and administration of taxes and strengthening tax-related institutions and develop local capital markets. Countries such as Mozambique, Nepal, and Rwanda have shown that large revenue increases are possible.

This brings me to my second policy priority: laying the foundations for inclusive, sustainable growth through transformational reforms and building strong state institutions.

History teaches us that poor countries become richer by educating people , putting in place good infrastructure, and ensuring effective governance with respect for the rule of law. These elements aren’t static: skills requirements change; infrastructure today includes digital connectivity and sophisticated trade channels; and institutions are evolving. All the same, these remain the three key pillars for growth and prosperity — for all countries, especially where the need to create jobs for fast-growing populations is most pressing.

Let me elaborate on these three pillars.

First and foremost is the need to invest in people. For Africa, this means expanding high-quality education at all levels, so that young people can seize the job opportunities of tomorrow. It also means scaling up investment in healthcare. Right here in Côte D’Ivoire, the government is stepping up investments in young people while taking measures to further diversify its economy.

Second, is the need to address infrastructure gaps—old and new. This of course means core physical infrastructure, as in the case of the new bridges here in Abidjan. But also, much needed rural road networks, extended electricity coverage and the like.

And these investments must embed the requirements of the green transition. This requires smart investments in adaptation, infrastructure, and technology, such as better irrigation systems. And there are strong growth opportunities in the energy transition.

Digital also falls into the infrastructure bucket. Much in the same way that electricity underpinned economic progress in 20th century, digitalization can propel progress in the 21 st century. It offers African countries the greatest chance to catch up.

And we already see many examples at work in the region in recent years. Kenya’s mobile payment service, M-PESA, expanded to six other countries in Africa, for higher payment efficiency and financial inclusion. Or take “Hello Tractor” , a platform that operates in several countries in sub-Saharan Africa and allows farmers to rent tractors by text message, creating new opportunities for more people.

African startups impress with their innovations. More investment in internet access will unlock the continent’s creativity and improve public services. During the pandemic, Togo rolled out a digital-payment program called Novissi, which delivered emergency cash transfers to populations in need.

The third pillar is the required improvement in governance and state capacity to foster inclusive growth. New IMF analysis [iii] shows what could be achieved across emerging and developing countries. A package of reforms focusing on cutting red tape, improving governance, and reducing trade restrictions, could lift their output by 8 percent in four years.

I would put the reforms required to realize the full potential of the African Continental Free Trade Area in this category. Removing trade barriers and improving the broader trade environment will push per capita income of the median African country up by more than 10 percent. Fully implemented, it will make Africa transform itself into the world’s largest free-trade area—delivering a big lift to living standards.

This brings me to the third policy priority—boosting collective resilience through international cooperation.

At the very time when we need it most, cooperation is weakening. The bridges that connect countries are corroding as trade and investment barriers are rising.

A fragmented world is especially challenging for emerging and developing countries, because of their greater reliance on trade and their more limited policy space. Compared with other regions, the African continent stands to suffer the biggest economic losses from severe fragmentation.

This is a challenge we must confront together.

In no other area is the need for international cooperation as evident as in addressing the existential threat of climate change. The world has a responsibility to stand with vulnerable countries as they deal with shocks they have not caused.

This is why we at the IMF created the new $40 billion strong Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST). It provides longer-term affordable financing to help lower-income and vulnerable emerging market economies to undertake climate reforms. We have already approved eleven programs, six of them in Africa, with many more to follow over the next year or two.

We also need to work together to help countries deal with debt challenges. One-fifth of emerging economies and more than half of low-income countries remain at high risk of debt distress.

Here, we have made significant progress in recent months. The Common Framework is starting to deliver, even if still too slowly. Together with the Indian G20 presidency and World Bank, we have set up the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, which brings together public and private creditors and debtor countries. For example, it took Chad 11 months to move from a staff-level agreement with the IMF to secure the creditor assurances needed for approval of the program; it then took 9 months for Zambia to reach this milestone, 6 months for Sri Lanka, and 5 months for Ghana. We would still like to see faster progress, but we’re moving in the right direction!

Even so, more needs to be done to support vulnerable emerging and developing countries. This is why we urgently need to strengthen the global financial safety net.

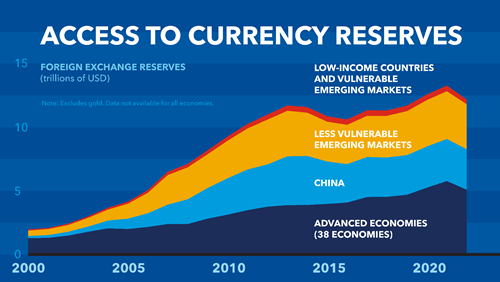

Currency reserves, central-bank swap lines, and regional financial arrangements offer some insurance against financial crises. But about 100 vulnerable emerging and low-income countries, including most countries in Africa, lack sufficient reserves and access to swap lines.

So, it is not surprising that they rely on support from the IMF, which stands at the center of the global safety net. In many cases, the IMF is the “insurer of the uninsured.”

Since the pandemic, we have deployed $1 trillion in global liquidity and reserves through our lending and the allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). We have provided around $320 billion in financing to 96 countries. We have increased five-fold our interest-free financing to 56 low-income countries through our Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT). And we have worked with economically stronger members to channel a significant share of their SDRs to more vulnerable countries, generating around $100 billion in new financing through IMF Trusts such as the PRGT and RST.

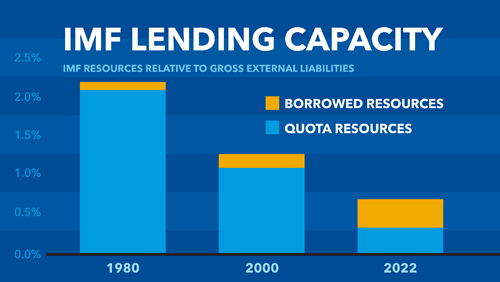

And yet the IMF’s lending capacity as a share of global external liabilities has diminished over the past few decades as financial markets have expanded. And the share of borrowed resources has gradually increased.

To strengthen this core of the global safety net, we are thus calling on our member countries to bolster the IMF’s quota resources.

We are also encouraging our stronger members to step in with more financing for the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, as well as our Resilience and Sustainability Trust, to ensure support for our vulnerable members.

A strong and adequately resourced IMF also means an IMF that is more responsive to the needs of emerging and developing economies. We have already taken strong actions in response to recent shocks, but we will continue to further strengthen our toolkit, including for our precautionary facilities.

The Fund, with its near-universal membership, plays a vital role in bringing countries together. This means also expanding the voice of emerging and developing countries. I am looking forward to our members agreeing to a third African Chair at our Executive Board.

We continue to tailor Fund support to each member’s particular conditions, and have increased our presence on the ground with a large networks of Resident Representative offices and Regional Capacity Development Centers, including right here in Abidjan.

Conclusion

Let me conclude by returning to 1973, the last time the Annual Meetings were held in Africa. Back then, delegates faced many of the same challenges we face now: high inflation, conflicts, and fundamental economic shifts.

In his speech at the Annual Meetings, Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta declared the “need for effective cooperation has never been greater.” And he finished with one word: “Harambee,” meaning “pulling together in full cooperation.”

With the right policies—and Harambee—we can build a bridge to a more prosperous and peaceful future. We can lay the groundwork for a half century even more impressive than the last.

On est ensemble!

Thank you.

[i] October 2023 World Economic Outlook, Chapter 2: “Managing Expectations: Inflation and Monetary Policy.”

[ii] October 2023 Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 2: “Identifying Weak Banks: A New Analytical

Approach.”

[iii] IMF Staff Discussion Note: Structural Reforms to Accelerate Growth, Ease Policy Trade-offs, and Support the Green Transition in Emerging Market and Developing Economies

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER: Tatiana Mossot

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org