Sellers and buyers in an outdoor bazaar in Egypt. COVID-19 will leave an indelible imprint on countries in the Middle East and Central Asia. (photo: Aleksej Sarifulin iStock by Getty Images)

How the Middle East and Central Asia Can Limit Economic Scarring in the Wake of COVID-19

November 19, 2020

The economic crisis stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic is the largest and deepest shock of its kind in recent history and could do lasting damage to economies in the Middle East and Central Asia.

In the recently released Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia, IMF staff explore this prospect and how countries can take steps to avoid economic scarring and improve their resilience.

Intuitively, economic scarring occurs when a crisis causes persistently lower production or weaker demand. The severity of scarring depends on a country’s preexisting conditions when a crisis hits and how a country subsequently responds. The global financial crisis, for example, led to significant scarring in the region. In fact, by the end of 2019, one-third of the countries in the region had not returned to their pre-crisis output trends, and for those who did, it took more than five years.

Why scarring is a threat now

Given the unprecedented nature of the current challenges and the already elevated fiscal and external vulnerabilities before the pandemic hit, countries in the Middle East and Central Asia face the daunting possibility that the impact of this crisis will linger for even longer than the global financial crisis. Our economic outlook estimates that, five years from now, countries in the region could be 12 percent below the GDP level suggested by pre-crisis trends—compared with 9 percent for emerging markets and developing economies. What’s more, a return to the pre-crisis trend could take more than a decade.

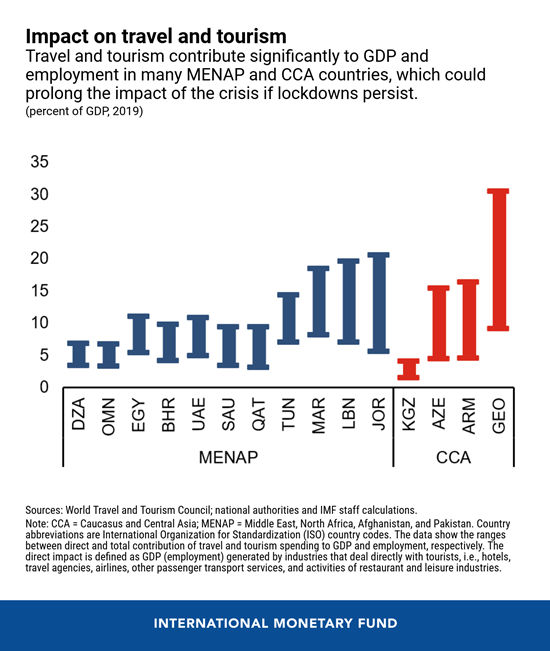

Scarring in the region could occur in a few key areas. First, continued containment measures expose services, especially travel and tourism, to severe disruptions and losses. In fact, for tourism-reliant countries—such as Georgia, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco—we project that baseline GDP and employment growth could go down by 5 percentage points each in 2020, with lingering effects for as many as five years.

Second, with higher leverage and lower profitability, corporates in the region entered the crisis in a weaker position than in past crises. Data from the first half of 2020 show corporate revenues dipped by 7 percent, and many sectors, like energy, manufacturing, and services, had double-digit drops. The damage to corporates in the region will likely take years to undo, raising the risks of corporate default in the medium term.

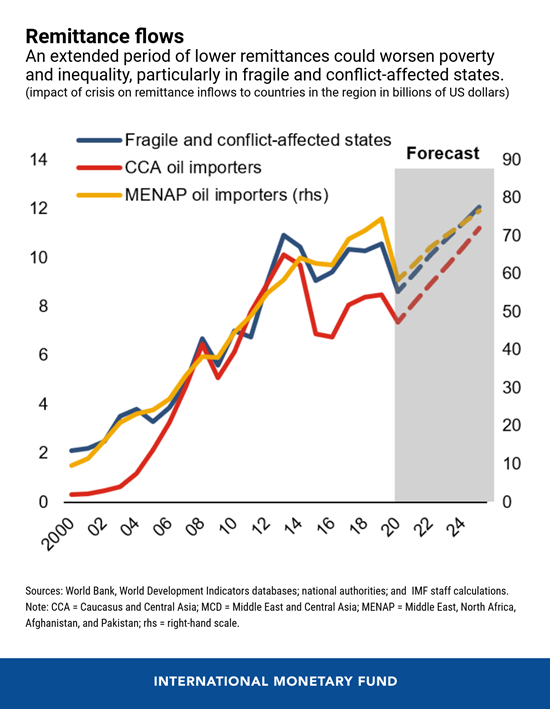

Third, remittances are estimated to have contracted by 23 percent on average during the first half of 2020. Persistently lower remittances will soften private demand and worsen poverty and inequality. Fragile and conflict-affected states, like Yemen and Sudan, and other remittance-dependent countries, such as Egypt, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan, could collectively see up to 1.3 million more people living in extreme poverty in 2020.

Finally, countries were beset by high unemployment even before COVID-19 spread, and the region’s limited ability to work from home and high degree of informality only worsened the impact of lockdowns on labor outcomes. Evidence from past shocks suggests that downturns in the region typically have long-lasting effects on the labor market, and unemployment spells can have enduring, damaging effects on an individual’s employment prospects.

Tackling the challenges ahead

All these factors point to a difficult path forward for the Middle East and Central Asia region. Fortunately, though, widespread scarring can still be avoided if authorities take swift and decisive action.

It will be essential to promote economic recovery without creating “zombie” sectors that are dependent upon government support. That means policies should only support viable businesses, while facilitating the retraining and reallocation of labor and capital away from sectors in permanent decline.

Measures such as temporary support for wages, interest subsidies, and tax deferrals will be essential to ensure that businesses have sufficient liquidity. If solvency pressures do arise, strong insolvency frameworks should be put in place for swift resolution to minimize adverse impacts on financial stability.

Throughout all this, the most vulnerable must be prioritized and protected. Spending on health, education, and social assistance should be protected, and innovative digital solutions to improve targeting and expand coverage should be explored. For countries with fiscal space and weak social safety nets, unconditional cash transfers could be considered on a temporary basis as better targeting is developed. Reequipping workers in the worst-affected sectors with skills needed elsewhere will be key to staving off prolonged unemployment. For expatriate workers, countries should encourage greater internal mobility, support employment retention, and bolster job-matching and search programs. Countries should also improve their digital platforms, which will boost labor market resilience and allow countries to harness the value of the digital economy.

COVID-19 will leave an indelible imprint on 2020 and beyond, with an unimaginable human and economic cost. However, with effective policies and determined action, countries in the Middle East and Central Asia can avoid a lost decade and emerge from the pandemic with strong prospects for a prosperous, inclusive, and more resilient future.