African countries are embracing renewables to accelerate energy access, but funding remains a challenge

In most of the world, energy demand continues to increase, but hundreds of millions of people in Africa lack basic access to electricity and cook using dirty fuels. According to a 2019 report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) 770 million people have no electricity—75 percent of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa—and 900 million lack access to clean cooking in the region. This can limit educational and business opportunities, as well as people’s economic prospects and well-being.

Missing the mark

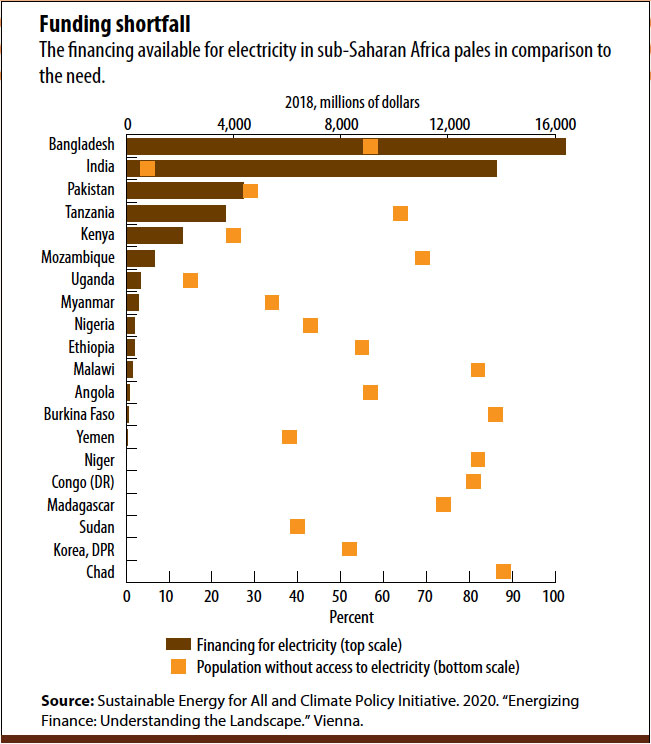

Closing the energy access gap in sub-Saharan African countries will require an estimated annual investment of $28 billion up to 2030, according to the IEA. This includes about $13 billion for mini-grids; another $7.5 billion is needed for grid and $6.5 billion for off-grid investments. Current financing commitments fall far short, with major gaps in countries such as Chad, Ethiopia, and Nigeria—all major population growth hubs. Similarly, the $131 million committed for clean cooking is just a fraction of the $4.5 billion needed by 2030. Countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ethiopia, where 95 percent of the population lacks access to clean cooking, receive less than 1 percent of the annual investment.

Significant financial commitments are needed to close this gap. However, challenges persist, including political instability, macroeconomic uncertainty (because of inflation and exchange rates), policy and regulatory issues, institutional weaknesses, and lack of transparency. All these make for a less favorable investment climate, alongside market failures and lack of aid to channel financing where it is needed most (see chart).

Several developed economies have already failed to deliver on their pledge of $100 billion annually in climate finance and are cutting foreign aid, at a time when investment needs to be doubled. The UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) and the Energy Transition Council should play a central role in driving urgent mobilization of capital for clean energy investment in the region.

Despite these challenges, there are successful initiatives that, if replicated, could help mobilize needed capital. For example, the Sustainable Use of Natural Resources and Energy Finance initiative—a French Development Agency facility—catalyzes commercial lending to the clean energy sector and has helped finance more than 60 projects in both commercial and industrial sectors, as well as on-grid projects across Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. It offers an integrated approach that provides banks and their clients with structured financing. It also offers technical assistance and support for companies in structuring their investments. The facility shares—through guarantee mechanisms—some credit risks borne by banks seeking to develop finance portfolios in renewable energy.

The Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa—a multi-donor fund established in 2011 and managed by the African Development Bank (AfDB)—has provided finance to unlock private sector investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency. Its technical assistance, as well as concessional and catalytic financing instruments, aim to de-risk investments in the sector and is targeted at green baseload power, green mini-grids, and energy efficiency. The fund facilitated the AfDB’s first two scale-up programs in Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of the Congo and played a key role in the development of energy blended finance initiatives. These initiatives include the Africa Renewable Energy Fund, which has catalyzed private sector funding through investments—for example, in Frontier Energy. Frontier Energy has invested over $1.8 billion in more than 45 renewable energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa, with a total capacity of more than 750 megawatts.

In 2020, the AfDB, through the Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa, committed $5 million to investment firms Enabling Qapital and Spark+ to raise equity for clean cooking companies in the region. This funding, together with €10 million from the European Union through its blending facility, has attracted many investors, helping to mobilize capital for investment in clean cooking.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.