Streaming video offers emerging markets an avenue for content at home and around the world

She is a beautiful Nigerian attorney. He is a dashing Indian investment banker. Just as their romance spans the international divide, the movie that immortalizes it is equally cross-cultural: filmed and produced in Nigeria, edited in India, and released by Netflix to a global audience.

Beyond a plotline of disapproving parents and saccharine-sweet dance numbers, the merging of Nigeria’s Nollywood and India’s Bollywood with the release of Namaste Wahala (“Hello trouble” in Hindi and Nigerian pidgin) represents how small the world of entertainment has become in a new age of streaming video.

Streaming giants like Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon are growing new audiences and overlapping markets in ways never seen before. In doing so, they’ve opened burgeoning film and television industries in some of the most vibrant emerging markets to new possibilities, changing the economic calculation for producing films and redefining what can be a hit.

“What’s beautiful about it is we’re sitting on the same platform. That’s what’s exciting—being a Nollywood movie—where it’s going, what we’re sitting next to in terms of Hollywood production and it being received in that way,” said Hamisha Daryani Ahuja, a third-generation Nigerian with Indian roots who created, directed, produced, and acted in the movie that Netflix released on Valentine’s Day.

Ahuja’s romantic comedy broke into Netflix’s top 10 list in the United States for a short period, generating buzz for the streaming company’s recent expansion into African content.

The growth of streaming services has only enhanced the entertainment industry as a driver of economic activity in large emerging markets like India, where by some estimates the sector accounts for 1 percent of GDP; Nigeria, where more than a million people work directly or indirectly for Nollywood—the second-highest employer after agriculture; and China, which overtook the United States in box office sales last year. Even though the pandemic has had an unavoidable impact, people’s desire to be entertained remains a constant, and the digitization of content is changing the rules of the game.

“I think right now we are at the beginning of a huge wave of international content and more investment in international content than we’ve ever seen,” said Stefan Hall, project lead for media, entertainment, and culture at the World Economic Forum.

Infrastructure is king

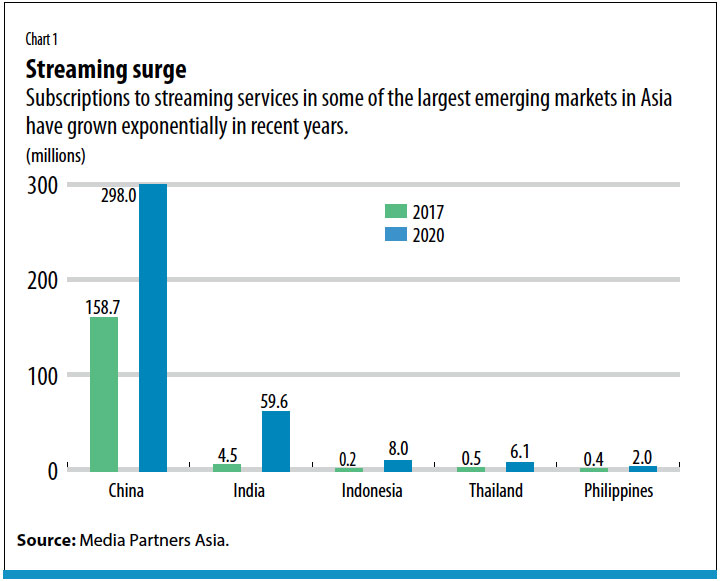

In Asia’s largest emerging markets, the growth of streaming services has exploded (see Chart 1). Subscriptions to video streaming services in India grew from 4.5 million in 2017 to 59.6 million in 2020. Indonesia saw growth increase from 200,000 subscribers in 2017 to 8 million in 2020. Thailand and the Philippines saw growth in the same period of 130 percent and 71 percent, respectively, according to Media Partners Asia, an independent research and consulting firm.

“In the last three to four years, there has been a mobile revolution in those markets, particularly in India, where you just had a massive data spike,” said Vivek Couto, the Singapore-based executive director of Media Partners Asia. “The landscape from an infrastructure perspective has multiplied.”

In India, rapid expansion in internet access has fueled fierce competition between the country’s largest telecommunications providers, which has driven down data prices to some of the lowest in the world. Most people access streaming video services on their smartphones, and India has some of the highest data usage per smartphone in the world.

In 2019, Netflix in India launched a mobile-only plan that would allow users to stream content to their smartphones or tablets for less than $3 a month. Netflix rolled out a similar plan in Malaysia. On the other side of the world, Spain-based Telefónica, one of the largest providers of telecommunications services in Latin America, announced in 2018 a multiyear partnership that would allow subscribers to seamlessly sign up for Netflix on its platforms across the region. In Africa, where internet service poses more of a challenge, the streaming service is working with telecommunications operators to make it easier for potential subscribers to make payments.

The trend has only accelerated with the COVID-19 pandemic. An annual survey of thousands of viewers from 10 advanced and emerging market economies found that nearly half of those surveyed subscribed to streaming services in the first half of 2020, with spending more time at home as the main reason.

This new level of connectivity in many countries has eased the entry of major streaming players, which has in turn redefined the possibilities and increased competition in the area of content creation.

While streaming services have made it easier for content to travel beyond a country’s borders to a regional market or a global audience, enticing and retaining subscribers who seek more options from their own countries remain a key focus.

In 2019, Disney+ acquired Hotstar, India’s leading streaming service, which now comprises 30 percent of the streaming service’s subscriber base. Netflix is steadily ramping up investment in the creation of local content in new parts of the world, including a new push into Africa last year with more original content. The streaming titan that started as a mail-order DVD rental service gained 36.6 million customers in 2020, its largest annual gain, and now boasts more than 200 million subscribers worldwide. After making a rare public apology in India in 2019 for a TV series deemed offensive to Hindus, Amazon gave no sign of retreating from the market after announcing in March that it would move beyond television shows and co-produce its first big Bollywood feature.

While US-based companies face some competition from domestic streaming services, they have come to dominate through a willingness to use their deep pockets to finance local content.

“The local content ecosystem is important,” said Couto. “As the big internet giants (Netflix and Amazon) and Disney grow within these big local geographies, their commitment to invest locally and grow the creative economy is critical because otherwise there will be a greater degree of hostility against them.”

A two-way street

Trade in cultural goods such as movies and music has always been fraught with cultural and political sensitivities. It still is.

European countries have long mandated that a certain portion of content broadcast, and now streamed, be locally produced. China has fashioned a landscape where foreign content is carefully monitored, giving rise to robust streaming dominated by Chinese players Tencent and iQiyi. Cultural sensitivities in India have forced large US companies to make course corrections to keep business growing.

But in markets where US-based giants like Netflix and Amazon operate, they’ve acted more as facilitators of free trade than cultural hegemons, said Joel Waldfogel, a professor of economics at the University of Minnesota.

“The happy surprise here is that this trade is a two-way street. So now it’s a horse race,” said Waldfogel, who studies how digitization of content has affected creative economies. “What we’ve seen in even the slightly longer run is the costs of producing things have fallen so much that there has been an explosion in creation in music and movies.”

Waldfogel argues in his 2018 book Digital Renaissance that digitization of content is ushering in a golden age of popular culture.

New technologies have put filmmaking capabilities into more hands. The internet, meanwhile, has expanded distribution channels. For movies that means bypassing traditional theaters and box office releases. Amid the pandemic, this trend has accelerated even in markets like India, where straight to streaming has lagged behind the United States.

Streaming services have elevated lower-budget productions and glossy high-dollar films to the same platform.

“Cultural products are extreme examples of products where it’s very hard to predict what will be good, meaning appealing to consumers at the time the investment decision gets made,” said Waldfogel. “There’s an expression in Hollywood, ‘nobody knows anything.’”

However, the rise of streaming services has taken some of the guesswork out of film production. In economic terms, the internet has created economies of scale and scope, meaning there is more supply and demand for greater quantity and variety of creative content. By matching viewers more easily with what they want to see, it has created a more efficient business model that can be adapted almost anywhere in the world.

That’s been good news for emerging markets with large captive audiences and the capacity to produce content. Streaming services from Netflix and Amazon have played a key role in providing another avenue for TV and film industries in these markets and increasing competition with domestic broadcasters.

“For a producer, there’s nothing more than to be seen beyond your natural geographic reach,” said Couto, of Media Partners Asia. “For the cultural entities of a country, whether they are governments or institutions, to have a story that showcases your country, that has those values and gives a global name to your content—that’s huge as well, because it all comes back in economic contribution.”

For Ahuja, the creator of Namaste Wahala, the opportunity came with an invite to a launch event with Netflix executives in Lagos in February 2020. Pre-release promotion of her movie had garnered attention. The movie was set to release in Nigerian cinemas in April 2020, but then the pandemic hit. The streaming giant provided an opportunity.

“I feel like this is a content market right now,” she says. “I don’t think there’s a limit on how much content can be put out there.”

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF and its Executive Board, or IMF policy.