The public and private sectors need to work together to promote gender equality

The responsibility for unpaid care work worldwide falls disproportionately on women and girls, leaving them less time for education, leisure, political participation, paid work, and other economic activities. Much of this work is devoted to caring for household members and doing domestic chores. Care work takes up a significant amount of time in most countries, especially where infrastructure is poor and publicly provided services are limited or absent (Samman, Presler-Marshall, and Jones 2016). The burden of care work is particularly acute in rural settings and in aging societies. This burden can limit women’s engagement in market activities and lead them to concentrate in low-paid, informal, or home-based work as a means of balancing unpaid care work and paid employment.

The disproportionate representation of women in low-paid and informal work contributes to gender wage gaps that undervalue women’s labor and inflate the numbers of the working poor. Securing a pathway to decent work and addressing unpaid care work are therefore fundamental to women’s economic empowerment.

To address these issues, the International Center for Research on Women has been working with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to explore how investing in care services and reducing care burdens can potentially increase women’s labor force participation. The goal of the project is to explore whether and how the private sector identifies and addresses care needs and responsibilities as important factors that limit their ability to hire, retain, and promote women. Part of this work includes forecasting how women’s labor force participation would be affected if care needs were resolved more effectively by the private and public sectors.

We know that men’s labor force participation is higher than women’s in all the countries where the EBRD works, with an average gap of 21 percent. The average gap in southern and eastern Mediterranean countries is higher, at 49 percent.

Drawing on recent country-specific studies that explore how women’s labor force participation changes with the price of childcare, we can estimate the impact of investing in this service (Gong, Breunig, and King 2010; Kalb 2009; Lokshin 2000). Harnessing these studies, we can hypothesize that if the price of childcare were reduced by 50 percent, the labor supply of mothers would rise on the order of 6 to 10 percent.

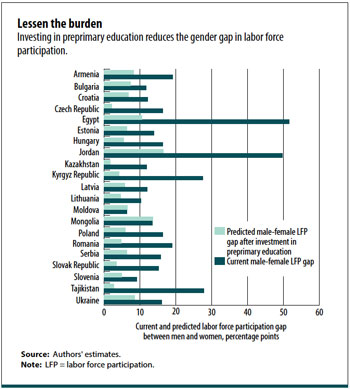

We developed a cross-country regression to estimate the labor force participation gap with respect to the cost of care in EBRD countries, and our estimates show that on average, increasing the share of government expenditure on preprimary education (as a percentage of GDP) by 1 percentage point can reduce the labor force participation gap by about 10 points.

Using this relationship, we forecast each EBRD country’s labor force participation gap after a 1.5 percent of total GDP increase in expenditure on preprimary education, the highest level of investment in the EBRD region (see chart). Doing so would bring down the average labor force participation gap from 21 to 6.5 percentage points. The biggest gains in women’s labor force participation are in countries such as Egypt, Jordan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan, where the average gap falls to 13.5 percentage points from 49 percentage points.

The role of the private sector

Exactly how we close the gap in women’s labor force participation by investing in childcare services, and who pays, depends very much on the constellation of actors who are affected. Our project with the EBRD focuses on Egypt, Kazakhstan, Romania, and Turkey and seeks to explore whether the private sector recognizes that failing to resolve care needs affects its ability to recruit, retain, and promote women. We explored the prevailing gender gaps in time dedicated to paid and unpaid work and dug deeper into the social norms and customs as they relate to the issue of care—who performs it, who should perform it, and the role of men.

We also examined the legislation, policies, and regulations that underpin the care options available in these four countries. The care policies considered ranged from direct provision of care services and care-related infrastructure to subsidies, tax credits, and care credits that can potentially expand the supply of child and dependent care and increase its affordability. We also looked at labor policies and regulations, such as leave policies and other family-friendly working arrangements, education and health sector policies, and macroeconomic policies that shape the fiscal space for care provision. Given the private sector lens of the research, the analysis paid specific attention to whether and how existing legislation regulated the private sector’s care practices and incentivized or reduced private sector involvement in care provision.

After interviewing managers, workers, and human resources staff, we found that even small companies experience costs from staff turnover associated with the failure to provide the kinds of care options that enable women to stay in the labor market after having children.

The case of Turkey

We found that in a medium-sized agribusiness company in Turkey of about 800 employees, more than 70 percent of whom are women, turnover posed a meaningful cost to the employer. The women employed in this agribusiness are mostly seasonal workers and are disproportionately represented in lower-skill and manual labor positions. The company provides maternity benefits in accordance with the law, including 16 weeks of paid maternity leave with provisions for another six months of unpaid leave. Breastfeeding mothers can take an hour and a half daily to nurse a child up to a year old. Fathers receive five days of paid paternity leave. The company does not provide childcare services or subsidies.

Employees in Turkey generally depend on family members, including older children at home, for childcare. Public childcare and education are available for children five and older. However, school hours are generally shorter than work hours, so family members must still help with drop-off and pickup. Where these support mechanisms are not available, women may quit their jobs to take care of their children.

In 2017, the company faced a turnover rate of over 26 percent of all women employees. Data from the human resources department and our interviews with workers and managers showed that 91 women quit every year for care-related reasons. The direct cost of recruitment and training, and the lost productivity as workers gradually learned all the skills required, came to almost $1 million a year—representing 14 percent of the company’s annual revenue. The average yearly cost of childcare for a child six months to three years old is $1,100, which means that the cost of childcare is lower than the total cost to firms of turnover and lost productivity. In another example, a small textile firm we worked with spends $258,000 a year on childcare for its employees but saves more than $800,000 as a result of lower women’s turnover.

Moving forward

The EBRD operates in many countries that currently don’t have enough public investment in care provision. The private sector can help fill in some of these gaps by either providing care services for employees or subsidizing access to these services. This can complement and reinforce existing public sector programs.

The provision of childcare can include a mix of solutions ranging from on-site care to subsidies. The extent to which this cost is shared between the private and public sectors is a matter of choice in each country. But as long as resolving care needs falls on individual households, the cost to firms will not be trivial, and they have a substantial stake in the resolution of these care deficits.

More broadly, this ongoing research highlights how lack of care and family-friendly workplace policies affects the company, community, and economy.

At the firm level it is evident that many companies need guidance about how to track the full costs of failing to address care needs and how best to accommodate more work-life balance policies. Many of the companies we engaged with had a particularly hard time calculating the costs of turnover or demonstrating the benefits of longevity and retention. They were even more challenged when asked about tracking measures of individual and collective productivity. At the community level, more research should look at the costs and benefits of greater access to care and improved functioning of labor markets. And at the macro level, we should calculate the benefits of investing in care in terms of the jobs and fiscal space created.

It is only by making the economic costs and benefits of care provision more visible that we will be able to change the dialogue around investing in care, and around redistributing roles and responsibilities between the market, the state, and the household with the goal of supporting universal access to quality care. Demonstrating that the failure to resolve care deficits affects the private sector as well may also be fundamental to ensuring the design of more holistic solutions that include taxation and subsidies to complement the public provision of care.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Gong, Xiaodong, Robert Breunig, and Anthony King. 2010. “How Responsive Is Female Labour Supply to Child Care Costs? New Australian Estimates.” IZA Discussion Paper 5119, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

Kalb, Guyonne. 2009. “Children, Labour Supply and Child Care: Challenges for Empirical Analysis.” Australian Economic Review 42 (3): 276–99.

Lokshin, Michael M. 2000. “Effects of Child Care Prices on Women’s Labor Force Participation in Russia.” Policy Research Report on Gender and Development Working Paper 10, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Samman, Emma, Elizabeth Presler-Marshall, and Nicola Jones. 2016. “Women´s Work: Mothers, Children and the Global Childcare Crisis.” Overseas Development Institute, London.