Published on June 28, 2022

Credibility is essential for sound fiscal policies

In response to COVID-19, both advanced and emerging market economies have implemented large fiscal stimulus programs that have pushed public debt to historically high levels. The combination of higher debt and challenging economic conditions has elevated default risks, tightened borrowing constraints, and triggered a wave of debt downgrades, especially in emerging market economies. These developments have heightened the need to plan for future debt reduction strategies, or deleveraging plans as they are commonly known.

Deleveraging plans are often centered on fiscal rules that constrain public spending. The IMF Fiscal Monitor (October 2021) highlighted the value of credible commitment to fiscal sustainability to improve market access conditions and thereby reduce the burden of debt. It encouraged governments to signal such commitment by improving their compliance with fiscal rules, entering IMF-supported programs, or legislating fiscal policy changes before tightening public finances (for example, in 2021 the United Kingdom legislated an increase in corporate tax rates for large companies that was to begin two years later). More broadly, a government can be considered to demonstrate a high level of commitment to fiscal policy if it can anchor the public’s expectations around the government’s fiscal targets. The government can gain fiscal credibility through clear communication, political will, strong fiscal frameworks, and building reputation over time by establishing a strong track record of meeting its announced objectives.

In this vein, David, Guajardo, and Yepez (2022) show that successful fiscal consolidation episodes—as measured by the decline in sovereign spreads (the difference between the interest rate on a US Treasury issue and a similar issue of another government)—have tended to be accompanied by IMF-supported programs. Similarly, End and Hong (2022) show that yields—returns on government debt—react more to fiscal consolidation announcements in countries with more credible fiscal reputations. Yet since there is little formal analysis regarding desirable debt paths during deleveraging and the role of commitment, in our new paper we compute optimal borrowing paths for governments facing default risk (Hatchondo, Martinez, and Roch 2022). We thus provide a benchmark to inform the design of deleveraging plans for highly indebted countries, and against which to compare simpler policies to enhance fiscal discipline.

Default risk

Eaton and Gersovitz (1981) developed a standard model of endogenous sovereign default (default risk is determined within the model and depends on domestic fundamentals) that was extended by Aguiar and Gopinath (2006) and has been widely used in studies of fiscal policy for countries with default risk. When a government lacks commitment to future fiscal policies (the standard assumption in this literature), the standard model features a debt dilution problem that generates a deficit bias and, thus, inefficient borrowing. Debt dilution refers to the reduction in the value of existing debt triggered by the issuance of new debt. A deficit bias refers to the tendency of governments to allow deficit and public debt levels to increase.

Rational investors anticipate that higher future fiscal deficits will increase the risk of default on debt issued by governments in the present and, therefore, they ask for a higher spread. The inability of governments to commit to lower future deficits reduces their ability to borrow today. Our model is calibrated to capture the historical relationship between the levels of aggregate income, sovereign debt, and spreads in economies facing default risk. Thus, model predictions match the average levels of sovereign debt and spread, the countercyclicality of spreads (default risk increases during recessions and decreases during booms), and the implied procyclicality of fiscal policy in emerging market economies (primary deficits tend to rise during economic expansions).

Our main contribution is to consider within this framework a government that has a credible commitment to future borrowing plans, which allows us to measure the value of commitment for the design of fiscal policy. The government with commitment improves welfare because it internalizes the debt dilution problem explained above when choosing its borrowing plan.

Value of commitment

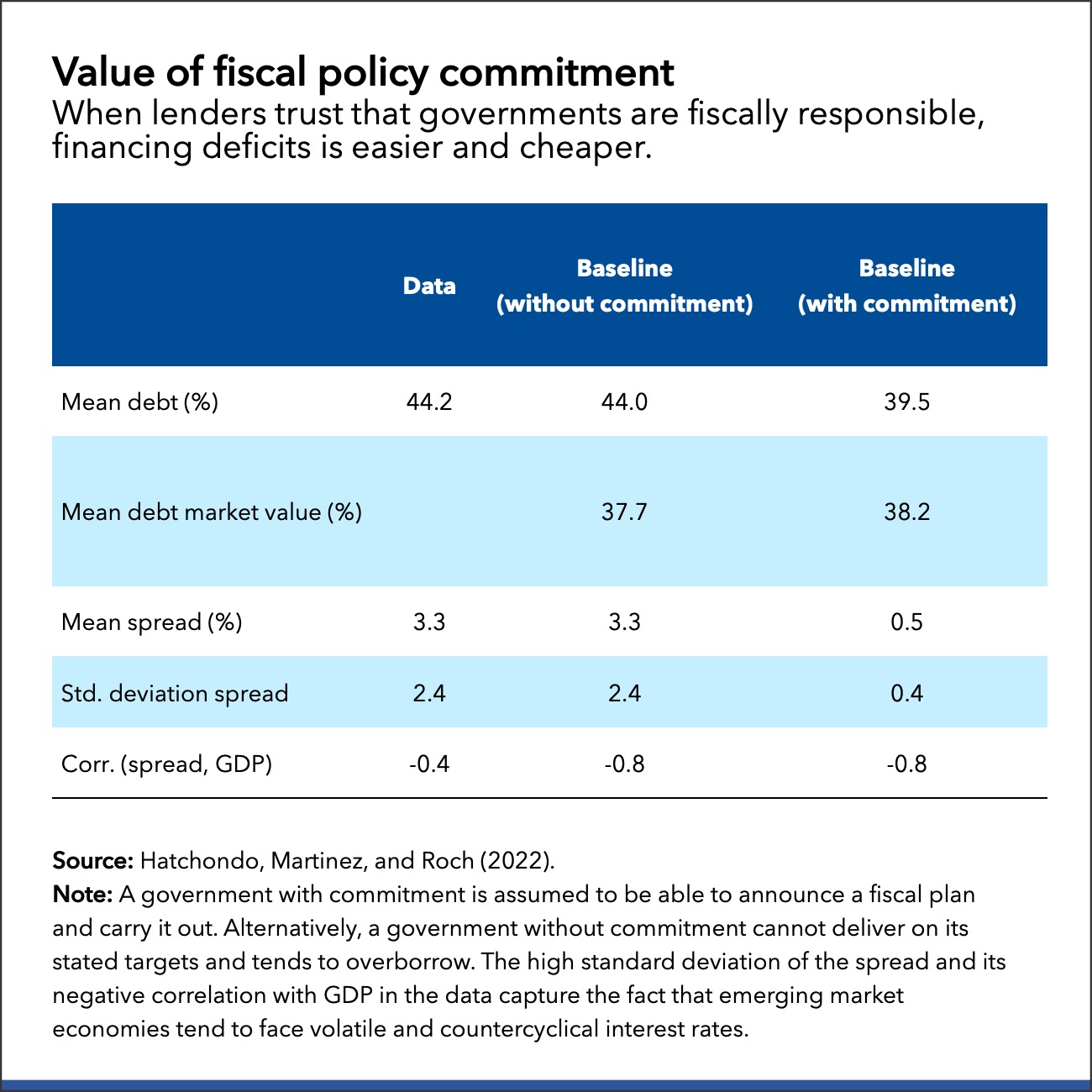

The table shows simulations from the model for governments with and without commitment. A government with commitment is deemed to carry out its announced fiscal plans, while a government without commitment would deviate from the plan and overborrow. The table shows that when lenders trust that governments are fiscally responsible, financing deficits is easier and cheaper. Transitioning from without to with commitment eliminates more than 80 percent of both the average level and the volatility of the spread. While the mean debt level is lower for the government with commitment, the mean market value of debt claims is higher, indicating that it does not borrow less on average to lower default risk.

We also quantify the importance of credible commitment to a deleveraging plan. We show that starting from a high debt level, a government with commitment has a higher probability of completing a successful deleveraging (without defaults). Our simulations suggest that

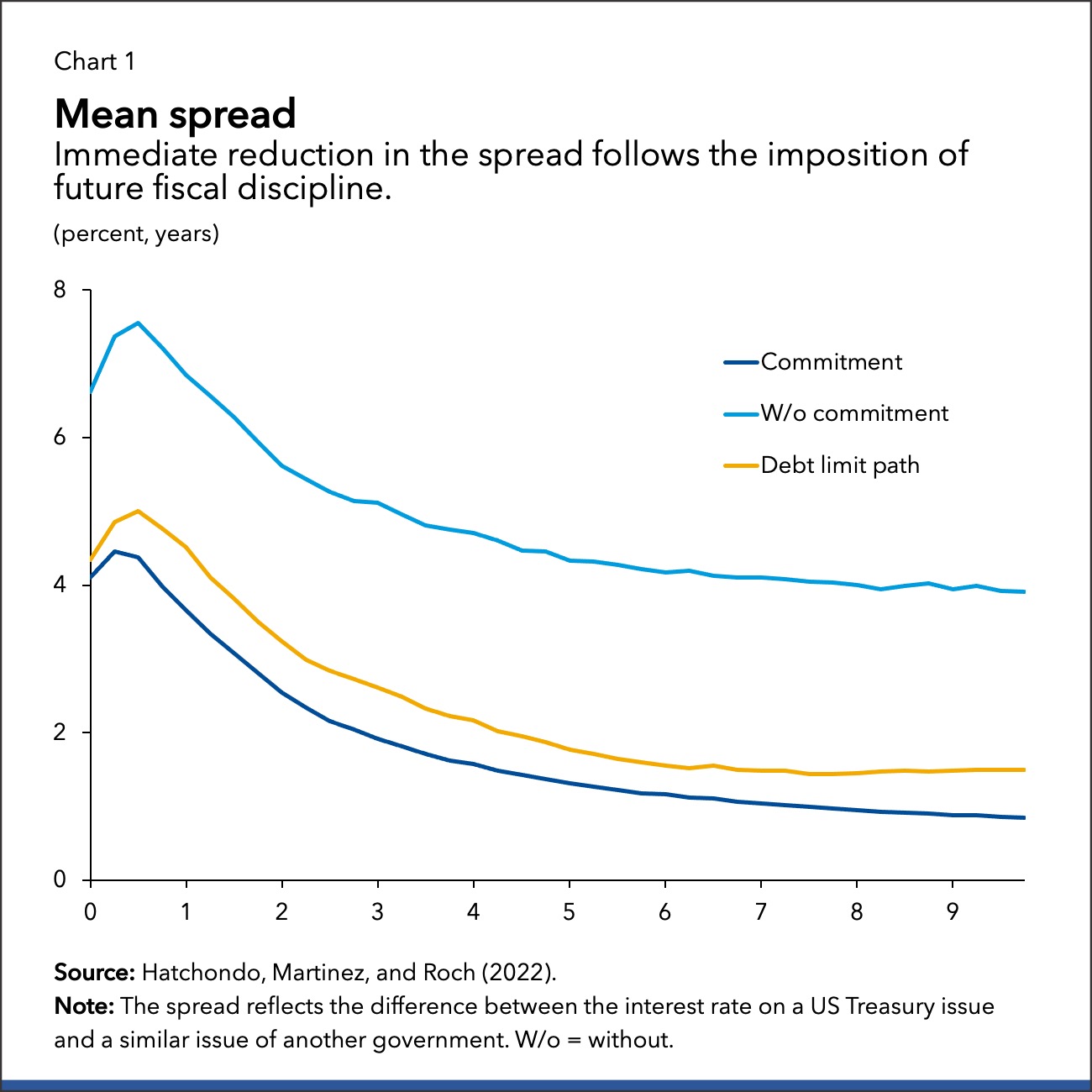

- Implementing the optimal plan with commitment cuts in half the probability of default within 10 years of the consolidation episode’s start. The lower probability of default with deleveraging under commitment is reflected immediately by lower sovereign spreads (Chart 1). Furthermore, we do not find any instance in which a high-commitment government would choose to default or a low-commitment government would choose to repay.

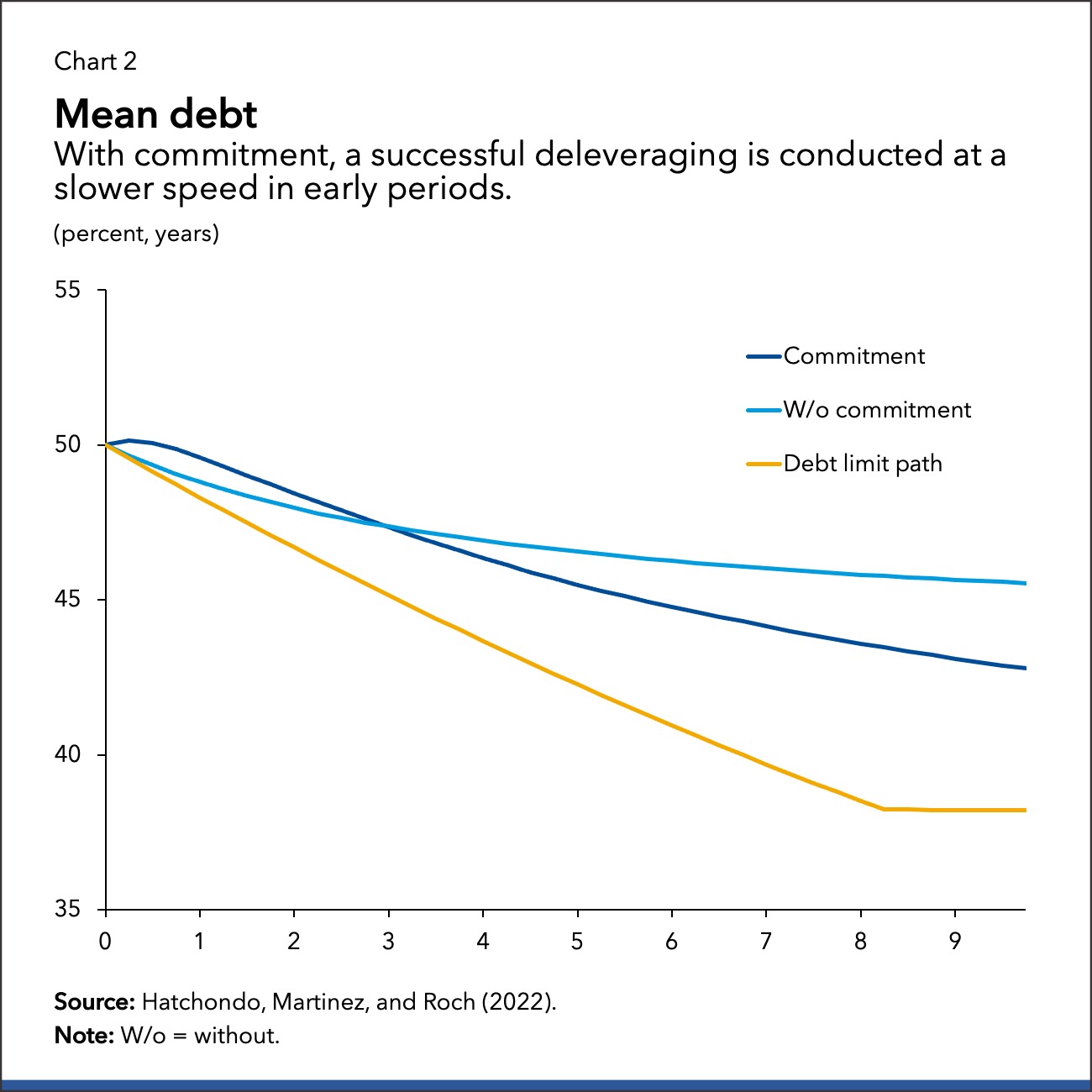

- By effectively reducing future default risk, a high-commitment government can afford to smooth the initial adjustment during the deleveraging path compared with the low-commitment government (Chart 2): it chooses slower deleveraging during the first year and reduces debt at a faster pace from the second year onward.

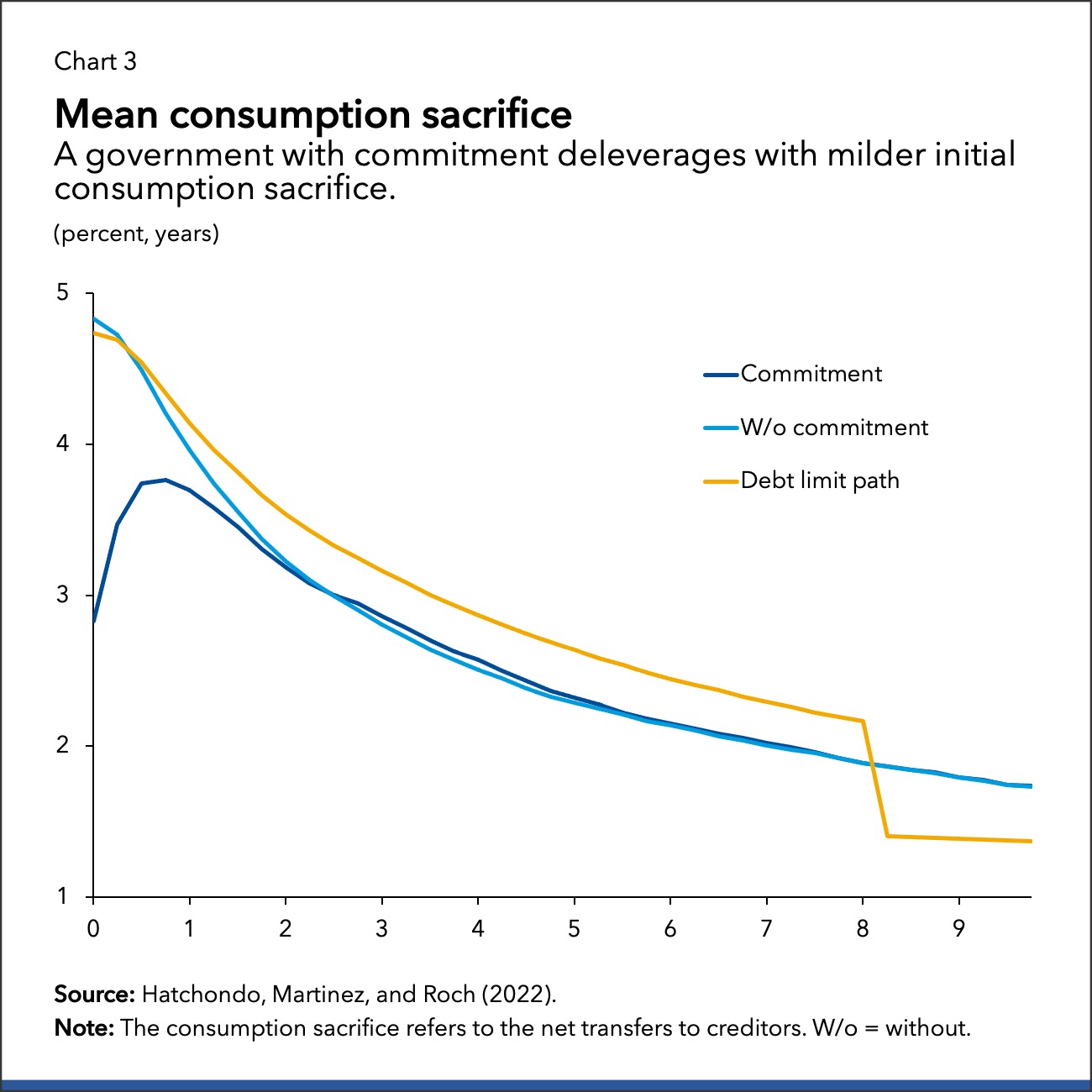

- The lower spreads allow the high-commitment government to implement a more successful deleveraging plan with less fiscal austerity (Chart 3). During the first six years of deleveraging, although the low-commitment government starts with a median saving ratio (the ratio of savings to income) of 5 percent that is eventually reduced to 3 percent, the high-commitment government starts with a median saving ratio of about 3 percent that is reduced only slightly over time.

A common practice in deleveraging plans, with the assistance of international financial institutions, is to set out goals for fiscal targets such as the primary deficit or debt. We approximate these policies considering a government constrained by a path of debt targets. For this, we envision a government that would not be committed to fiscal responsibility when unconstrained (a government without commitment) but that must comply with a long-lasting fiscal constraint (for instance, in the context of an IMF-supported program). In this scenario we consider a debt limit path that consists of an optimal long-term debt ceiling and a sequence of debt ceilings during the transition toward the long-term target.

We find that the constrained government imposes excessive austerity relative to the optimal plan chosen by the high-commitment government (Chart 3). The latter imposes austerity only when economic conditions are such that spreads are most sensitive to austerity, while placing milder constraints otherwise. In contrast, a debt limit constrains borrowing in almost all periods, even when not fully necessary. Consequently, it deleverages much faster (Chart 2).

The high-commitment government is more successful in reducing the spread than the constrained government (Chart 1), in line with the results in David, Guajardo, and Yepez (2022) and End and Hong (2022). The inability to fine-tune when stronger austerity should be imposed leads to a lower welfare gain than with a high-commitment government: the optimal deleveraging with debt limits achieves 60 percent of the welfare gains achieved by the optimal plan.

Overall, these results are indicative of the quantitative importance of enhancing long-term fiscal discipline to reduce sovereign risk and for the success of fiscal programs aiming at reducing debt levels. Following End and Hong (2022), a medium-term fiscal consolidation plan is deemed credible when the public expects the government will achieve its objectives (for example, when private forecasts are aligned with official announcements). Clear communication, strong fiscal institutions (for example, fiscal rules and fiscal councils), a good track record on past fiscal performances, and political will are all required to enhance fiscal credibility.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Aguiar, M., and G. Gopinath. 2006. “Defaultable Debt, Interest Rates, and the Current Account.” Journal of International Economics 69 (1): 64–83.

David, A., J. Guajardo, and J. Yepez. 2022. “The Rewards of Fiscal Consolidations: Sovereign Spreads and Confidence Effects.” Journal of International Money and Finance 123 (May): 102602.

Eaton, J., and M. Gersovitz. 1981. “Debt with Potential Repudiation: Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Review of Economic Studies 48 (2): 289–309.

End, N., and G. Hong. 2022. “Trust What You Hear: Policy Communication and Fiscal Credibility.” Unpublished.

Hatchondo, J., L. Martinez, and F. Roch. 2022. “Constrained Efficient Borrowing with Sovereign Default Risk.” Unpublished.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2021. “Strengthening the Credibility of Public Finances.” Fiscal Monitor, Washington, DC, October.