Sharply higher borrowing costs, especially for housing, fueled a disconnect between inflation statistics and consumer sentiment

Americans are, at last, starting to feel more cheerful about the economy. Consumer sentiment, as measured by the University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment, rose in March to the highest level in almost three years. Sentiment has softened since, but consumers for the most part seem to think that their fortunes are on the up.

It’s about time. Americans have been unremittingly miserable about the state of the economy since the pandemic. Consumer sentiment sank to the lowest level on record as inflation surged to a 40-year high in mid-2022. It stayed stubbornly down in the depths for much of 2023 despite a slew of indicators pointing toward a broader economic recovery, including stronger growth, rising employment, and slackening inflation.

Economists have puzzled over this apparent paradox: their predictions of how people would respond to positive economic news didn’t square with the persistent broadly negative consumer sentiment. Some argued that it takes time for people to benefit from slower inflation, others spoke of bad vibes, while still others pointed to high prices for the goods consumers value most, such as gasoline and groceries. Researchers have bundled these theories and others into the “referred pain” hypothesis. It suggests that noneconomic concerns may now drive economic sentiment.

We don’t dismiss any of these arguments. But in a recent paper with Harvard’s Karl Oskar Schulz we argue that this explanation overlooks a crucial mechanism that economists and policymakers appreciated more in the past: the rising cost of money.

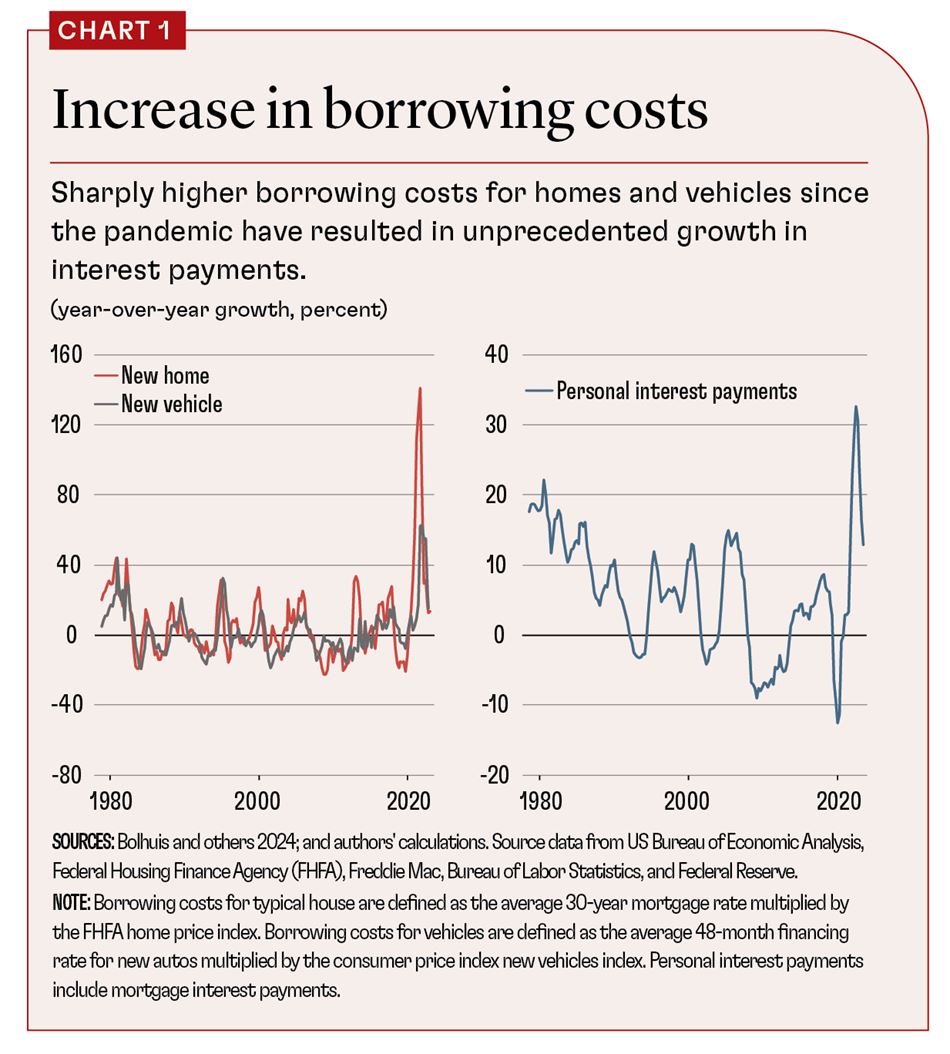

For consumers, the cost of money is part of the cost of living. Thus, as interest rates leapt to 20-year highs in the second half of 2023, consumers felt the financial squeeze. Home prices in the US are still up more than 50 percent since the start of the pandemic, and mortgage rates have roughly doubled. The interest payment on a new 30-year mortgage for the average house is up almost threefold since the end of 2019. The payment on a new car loan has nearly doubled. As a result, households’ interest payments grew by about 30 percent in 2023, the fastest rate on record (see Chart 1).

None of these increases, however, are captured directly by the consumer price index (CPI). This was not always the case. When Arthur Okun introduced his “misery index” in the 1970s, which combined inflation and unemployment, the Bureau of Labor Statistics included mortgage rates and car financing rates in the CPI. It removed these two components in 1983 and 1998, respectively. Today’s misery index, therefore, misses key components of consumer spending.

The statistics bureau took mortgage rates and car financing rates out of its index for good reasons, and we don’t think it should restore them. But we do believe that this gap in the current measure is crucial to understanding the state of the American consumer. Once this change is addressed, it’s possible to test the other hypotheses.

Missing money

We make our argument in three steps. First, we show that variation in the University of Michigan consumer sentiment index that cannot be explained by inflation and unemployment has historically shown a strong correlation with proxies for higher consumer borrowing costs.

It’s possible to group underlying data in the university’s survey into concerns about income and concerns about the cost of living. Income concerns reached a low comparable to the prepandemic level in 2023. Such worries were thus consistent with an environment of low unemployment and do not explain the consumer anomaly.

Concerns about the cost of living tend to correlate strongly with official inflation. They peaked during the inflationary cycle of the early 1980s, the early 1990s, the late 2010s, and the recent post-COVID period. The share of cost-of-living concerns that cannot be explained by variations in official inflation has increased sharply during this cycle, however. This unexplained piece correlates strongly with both the real growth of interest expenses for mortgages and the banks’ willingness to make consumer installment loans. These results suggest that excluding the cost of money from official measures explains a lot about the gap between consumers’ level of concern and official inflation rates.

Borrowing costs

In addition, we show that other questions in the survey offer direct evidence that consumers’ worries about borrowing costs reached record highs in 2023, surpassed only during Paul Volcker’s chairmanship of the Federal Reserve from 1979 until 1987. We construct an index that summarizes variations in answers to questions about borrowing costs for durable goods, vehicles, and homes.

Consumer concerns over interest rates show two clear peaks. The first is during the Volcker era, when the federal funds rate and mortgage rates spiked above 15 percent. Concerns dropped sharply after the Fed eased policy in 1982. The second peak in consumer concern occurred in 2023. As interest rates begin to come down, this measure should improve.

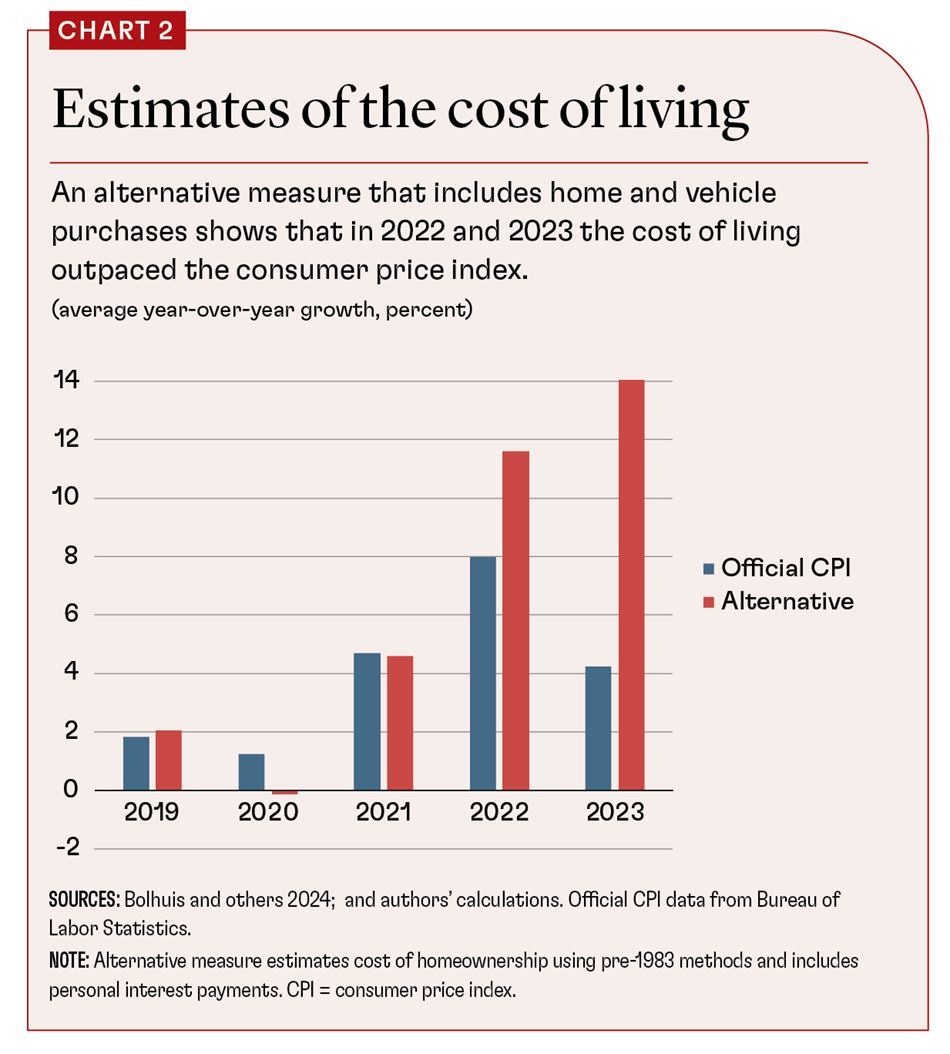

Finally, we present alternative measures of the cost of living that explicitly incorporate the cost of money. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ current methodology relies solely on the rental market to explain changes in owners’ equivalent rent (Bolhuis, Cramer, and Summers 2022). Before 1983, the CPI included a measure of the cost of homeownership that reflected mortgage rates and home prices. Similarly, the official statistics exclude borrowing costs for vehicles and other personal interest payments (credit card debt, for example) that better reflect actual costs borne by consumers.

With these points established, we present alternative CPI measures that reflect mortgage interest payments, personal interest payments for car loans and other nonhousing consumption, and vehicle lease costs. Our main alternative inflation measure reconstructs the pre-1983 CPI measure and expands it using the costs of homeownership and personal interest payments. These alternative measures show both a much higher peak and continued high inflation throughout 2023 (Chart 2).

Our alternative methodology for CPI inflation does much to solve the puzzle of continued depressed consumer sentiment in an environment of low unemployment and falling official inflation. Throughout 2023, the consumer sentiment gap, after accounting for unemployment, official CPI inflation, and growth in the US stock market, was at record levels. Accounting for the costs of homeownership and personal interest payments closes more than two-thirds of this gap for 2023.

Since the release of our paper, some scholars have suggested that the factors that most affect consumer sentiment are gasoline and grocery prices rather than borrowing costs. We find, however, that the gap is practically unchanged, even after we account for changes in grocery and gas prices.

Tangible explanation

The gap between economists’ measurements of economic well-being and what consumers actually said they were feeling puzzled many researchers. Commentators spoke of a “vibecession”—a recession experienced not in rising costs of living or growing unemployment but in “vibes”—by the middle of 2023. Did poor consumer sentiment—which should have been overwhelmingly positive given strong GDP growth, declining prices, and continued job creation in 2023—presage a recession? Would everything turn around if gasoline and grocery prices fell back to more normal levels?

We present a more tangible explanation for the departure of consumer sentiment from economic fundamentals: how consumers feel about their own economic well-being includes the cost of money. Economists and official measures miss this crucial component.

The sentiment gap seen in 2023 was not unique to the US or to this cycle, our work shows. Consumers worldwide digested economic data in a way consistent with consumer sentiment during previous bursts of high inflation and rising interest rates. Evidence across countries confirms that consumers around the world care about the cost of money: the countries that saw the largest spikes in borrowing costs were usually those where consumer sentiment undershot fundamentals the most. We found little evidence that the US—despite rising partisanship, social distrust, and extensive reports of overall “referred pain”—differed meaningfully from other Western democracies.

Since the release of our paper, there has been greater recognition that housing costs are a leading concern for consumers in rich countries (Romei and Fleming 2024). Lower interest rates are not a panacea for the sclerotic housing market in the US and beyond, but they could help lift consumer sentiment if more housing is built and people have better access to affordable financing. If the housing supply remains depressed and lower interest rates only inflate prices, consumers may wind up even more pessimistic than the misery index suggests.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Bolhuis, M. A., J. N. Cramer, and L. H. Summers. 2022. “Comparing Past and Present Inflation.”, Review of Finance 26 (5): 1073–100.

Bolhuis, M. A., J. N. Cramer, K. O. Schulz, and L. H. Summers. 2024. “The Cost of Money Is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly.” NBER Working Paper 32163, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Romei, V., and S. Fleming. 2024. “Concern over Housing Costs Hits Record High across Rich Nations.” Financial Times, September 2.