Global institutions must coordinate to preserve the goods that benefit us all

The COVID-19 pandemic, refugee crises, climate change—these global problems have exposed the need for public goods that are likewise global. What are public goods, and how can they be supplied globally?

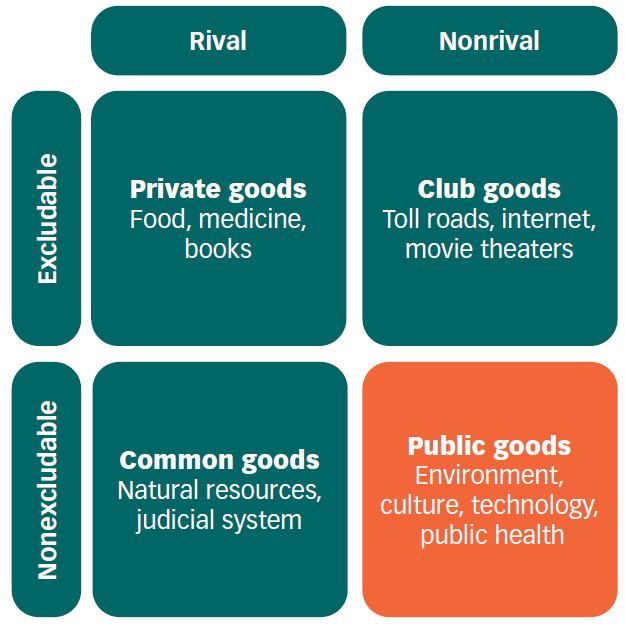

Public goods are those that are available to all (“nonexcludable”) and that can be enjoyed over and over again by anyone without diminishing the benefits they deliver to others (“nonrival”). The scope of public goods can be local, national, or global. Public fireworks are a local public good, as anyone within eyeshot can enjoy the show. National defense is a national public good, as its benefits are enjoyed by citizens of the state. Global public goods are those whose benefits affect all citizens of the world. They encompass many aspects of our lives: from our natural environment, our histories and cultures, and technological progress down to everyday devices such as the metric system.

No one can be prevented from using the metric system, and whenever someone uses it its usefulness to others is not diminished. The nature of their benefits sets public goods apart from the private goods we see in the store or the club goods we can pay a fee to access, but this also means they cannot be found in a store nor accessed via a simple fee. Creating public goods is much more difficult than supplying private goods, and providing global public goods poses a unique challenge.

Why are public goods undersupplied?

Simply put, incentives are lacking. For a profit-seeking individual to supply a public good, the expected benefit to that individual must exceed the cost. For public goods, the opposite typically applies for several reasons:

- Individuals cannot be charged for their use. Because of the nature of public goods, the supplier cannot prevent individuals from using them. Once supplied, all people can use a public good whether or not they contributed to its provision. This is known as the “free rider problem.”

- For most public goods, the benefit to each individual is small. This is often the case when one person’s use of a good affects others. These “spillovers” or “externalities” can render the benefit for any single individual too small (if the spillovers are positive) or too large (if the spillovers are negative). This is the case for goods such as global health—by choosing to be vaccinated, a person stays healthy (individual benefit that may be small for those not at risk) and prevents others from getting sick (a large positive spillover).

- For many public goods, the benefits are realized far in the future while the costs are realized today. People tend to overvalue the present relative to the future. This short-sightedness can distort the costs and benefits from goods such as education (the cost of schools is paid today, while the benefit is realized when the students become adults) and the natural environment (the cost of mitigating climate change is paid today, while the benefit is mostly for future generations).

For these reasons, public goods will tend to be undersupplied if left to the private sector.

To date, the solution to the problem of providing public goods has been coordination, which ensures that everyone contributes to the provision of a public good and that the costs and benefits are weighed without distortion. Formal institutions, notably governments, are the main coordinators in the provision of local and national public goods.

Governments are most successful in providing public goods when they have strong institutions. By enforcing regulation and taxation, governments mobilize resources to provide public goods and eliminate the free rider problem. An inclusive government values the welfare of all its citizens—those within its borders and across generations. Such governments are able to realize the full societal benefit of public goods (the sum of individual benefits as well as the spillovers) and to balance the needs of present and future citizens.

Are global public goods different?

Theoretically, global public goods are no different from local or national public goods. They are nonexcludable and nonrival. They are characterized by free rider problems, spillovers, and short time horizons. Why, then, are more local and national public goods provided than global public goods? Why is there more funding for national defense than for combating global climate change?

The failures of governments that underprovide public goods are amplified when it comes to global public goods. Global institutions—where they exist—often lack the legal authority to enforce regulation and taxation or the institutional capacity to coordinate the needs of all citizens in the world and across generations. The coordination challenge is also bigger. Global institutions deal with national governments, as opposed to individual citizens. National governments have very different incentives from individual citizens, both economic and political, and many struggle to provide public goods even within their own countries.

The ratification of the Paris Agreement was both a success and a testament to the limitations of international coordination. By making allowances for countries’ different needs and responsibilities, the agreement takes into account the welfare of each country. The commitment by developed economies to provide $100 billion in climate financing each year mobilized resources for emerging market and developing economies. However, the withdrawal of the United States in 2020 and the chronic underprovision of climate financing highlight the agreement’s limited ability to enforce contributions and to eliminate the free rider problem.

Supply and demand

It is not inevitable, however, that the world will continue to fail to provide global public goods. Many institutions that provide public goods today did not appear on their own, but formed in response to demand. Public education in the United States developed in response to citizen demands in a technologically advancing world. The IMF was established after the Great Depression and World War II as countries recognized the need to promote global financial stability.

Note: Goods listed are examples; this is not an exhaustive list.

There is reason to believe that the demand for global public goods is growing. Whether it is trade, capital flows, or migration, the world is far more interconnected now than it was in 1945, when many global institutions such as the United Nations, IMF, World Bank, and World Health Organization were founded. The importance of global public goods in our everyday lives becomes more salient with each new crisis—COVID-19 has increased demand for global public health, refugee crises for global peace, climate change for sustaining the global environment. These crises require a global framework that recognizes a shared obligation, clearly delineates each country’s responsibility, and enforces these commitments. For global institutions to foster coordination, they need comprehensive governance structures to ensure that decisions are legitimate and represent all present and future citizens of the world. If the momentum that is building today can be harnessed and mobilized to build this global framework, the provision of global public goods may become a reality.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.