The Global Economy and Financial Crisis, Speech by John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director, International Monetary Fund, At the UCLA Economic Forecasting Conference

September 24, 2008

Speech by John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director,International Monetary Fund

At the UCLA Economic Forecasting Conference

September 24, 2008

| Download the presentation (564 kb PDF) |

As Prepared for Delivery

Introduction

The past few weeks included momentous and almost unimaginable financial sector developments. What began more than a year ago with market turmoil surrounding U.S. subprime mortgages, last week became a financial storm of historic proportions—engulfing the largest US insurance company and encompassing the largest US bankruptcy. Following their intervention in the two mortgage giants—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—U.S. officials announced sweeping actions to head off wider market disruptions, including plans to purchase distressed mortgage-related securities on a massive scale, as well as a one-year guaranty of money market mutual funds. Finally, the two largest stand-alone investment banks announced that they were converting themselves into bank holding companies. Thus, before our eyes, financial tectonic plates shifted, wiping away an institutional form—the large, independent investment bank—that as recently as mid-2007 were viewed popularly as financial giants reaping huge profits. Other countries also have experienced serious turmoil in their financial systems, albeit not on the scale seen in the U.S.

Against this backdrop, I will address two basic issues:

• First, what are the macroeconomic implications of this financial storm for the global economy, in combination with the major commodity market shocks of the past year, and the housing downturns emerging in several advanced economies? There is a consensus today that the global economy is set to weaken further. Already, growth is slowing in both advanced and emerging economies. Looking forward, a key issue is whether the slowdown will be shallow and will be followed by a gradual recovery, or whether the downturn will be deep and protracted.

• Second, what can policies do to help to navigate the storm and to chart a course that would restore the financial system and support economic activity, while keeping inflation at bay ? The challenges are daunting. As recent developments suggest, many of the policy actions taken previously in the event were not sufficient to achieve these basic goals.

Notwithstanding the very real risks and concerns, my message today is, on balance, positive. According to IMF analysis, the latest challenges have not altered our core expectation of a gradual 2009 growth recovery. In particular, a global recession can be avoided, provided that coherent and effective policy responses are implemented around the world.

• Policymakers' first priority in the affected economies must continue to be the restoration of market functioning, forestalling the spiraling crisis of confidence among financial market participants. The unprecedented policy responses of the past few days—principally, but not exclusively, in the United States—have demonstrated that monetary and fiscal authorities are willing to implement innovative and unorthodox measures when they perceive that they are necessary.

• Of course, the recent financial turmoil has justified a modest reduction in our baseline forecast for global growth, but will not by itself prevent a gradual recovery beginning in 2009. Financial sector strains will weigh on credit growth and notably dampen the recovery's pace. At the same time, energy and commodity prices have receded, and inflation pressures should begin to ease—increasing the scope for future monetary policy moves in several advanced economies. Moreover, non-financial corporate sectors in many key economies—especially outside the automotive and housing sectors—have entered this difficult period in a relatively strong financial position, and appear to be able to withstand a period of tight credit markets.

In my presentation today, I will summarize our view of the global outlook, and then turn to the policy measures that we see as necessary to keep the global economy advancing, while avoiding the risks of either a sharp downturn or meaningful deterioration in inflation prospects.

Global Conjuncture

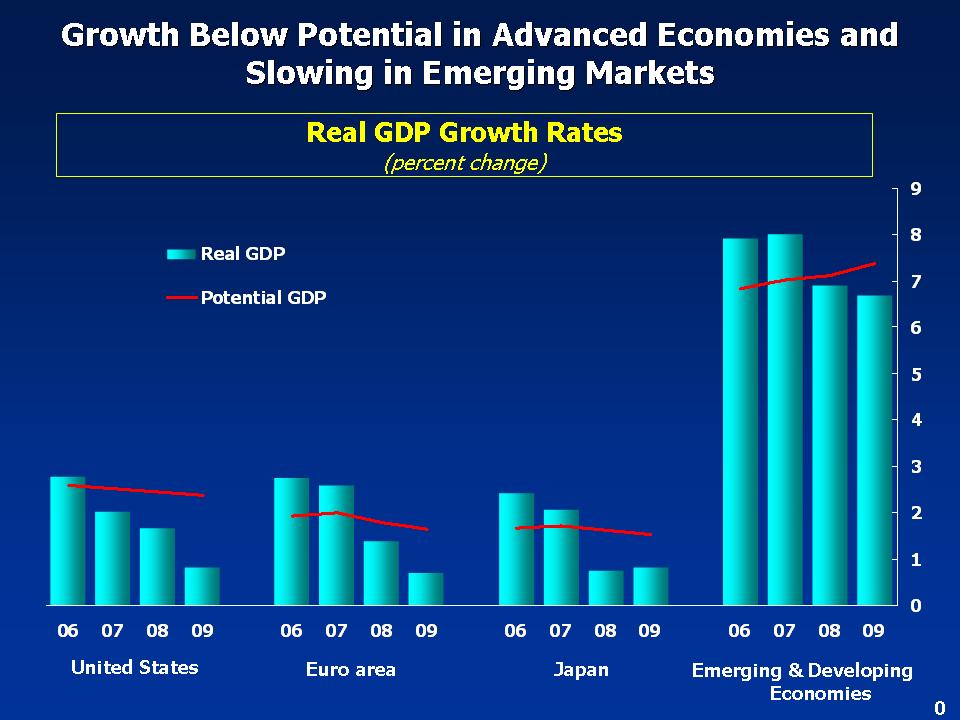

Advanced and emerging economies are moving in the same direction—that is, growth is slowing everywhere—effectively ending earlier hopes of a growth decoupling. The marked slowdown in global activity is being led by major advanced economies, which are either close to recession or experiencing growth far below potential.

• In the United States, housing and credit markets remain at the core of the slowdown.

• The growth slowdown has spread to Europe and Japan, amid weak business and consumer sentiment, terms of trade losses, weaker partner country growth, the impact of strong currencies on trade, and tightening credit conditions.

• Activity also is decelerating in emerging and developing economies, although growth in these regions remains high and close to trend, in large part reflecting the strength of domestic demand.

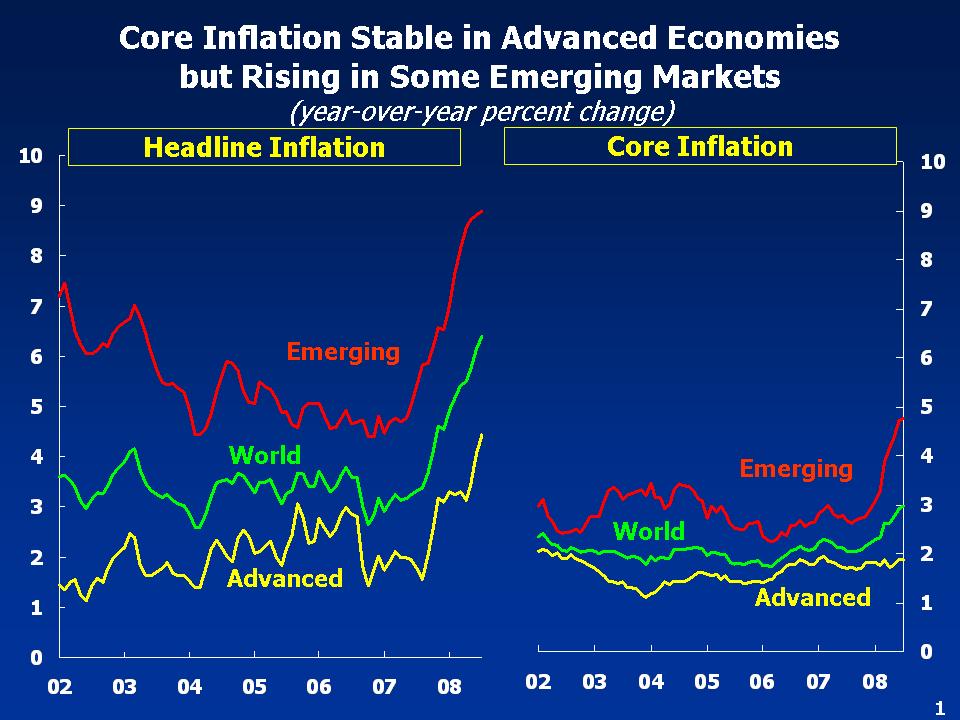

Despite weakening global growth prospects, inflation has risen around the world to the fastest pace since the 1990s.

In the advanced economies, headline inflation accelerated to around 4½ percent in July, driven mainly by oil price rises. However, underlying or core inflation has remained contained and, with commodity prices now in retreat, inflation is expected to moderate quickly, notwithstanding the recent—probably temporary—oil price increase.

The inflation resurgence has gone much further in emerging and developing economies, although risks have receded recently. Headline inflation climbed to about 9 percent in the aggregate by mid-year, and a wide range of countries are experiencing double-digit inflation. Underlying inflation has increased markedly in these economies, underscoring their less well anchored inflation expectations and the capacity pressures stemming from still-rapid growth. But the balance of risks between inflation and growth is shifting for many emerging economies—an issue to which I will come back later.

Global Shocks

This overall state of affairs in the global economy reflects the confluence of three major shocks: high commodity prices, the housing downturn affecting the United States and several other advanced economies, and the financial crisis. The interplay of these shocks has made policymaking much more difficult. Let me discuss how the shocks and their effects are unfolding.

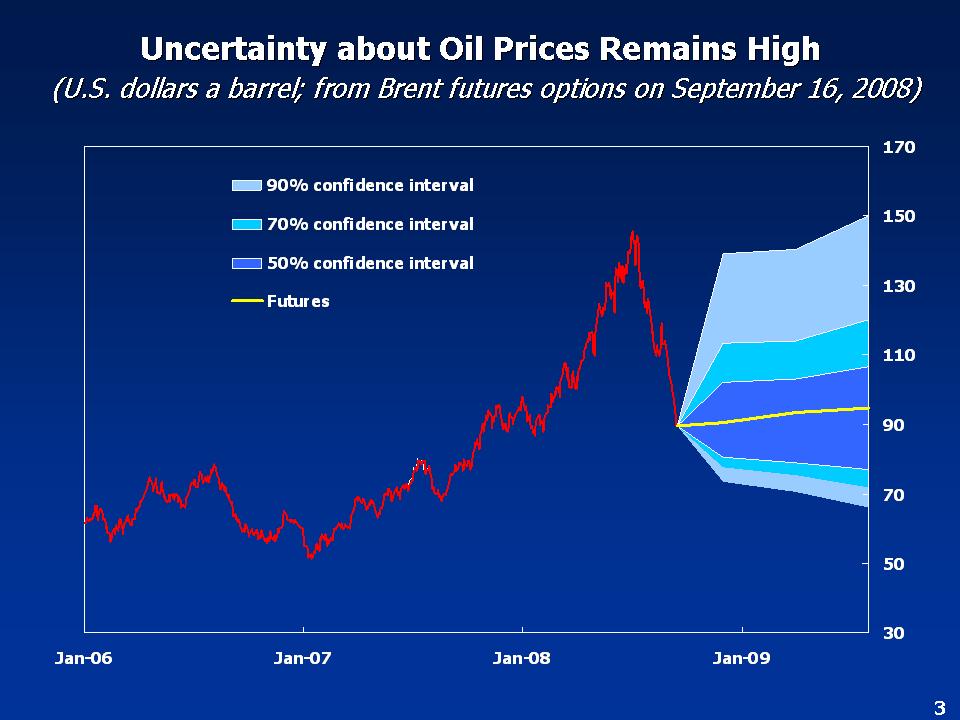

Commodity prices have retreated recently, but are expected to remain high and volatile. The prices of major agricultural commodities have moderated, although the pass-through to food prices may be more drawn out than for oil and energy prices. Nevertheless, if the trends in commodities prices are sustained, this would help create new space for countercyclical monetary, and in some cases, budgetary policies.

• Oil prices have moved off their highs, but uncertainty remains high. Crude oil prices have declined about 25 percent from the mid-July peak, but they are still about 10 percent higher, on average, than at the beginning of 2008 and oil prices have risen in recent days. Increasing signs of weaker global growth, indication of some demand response to higher oil prices, and improvements in supply conditions have led to the price decline. As for "speculation," our economic research finds very little hard evidence that would suggest this has been a driving factor systematically, although it is quite possible that shifting investor sentiment has amplified short-term oil price fluctuations.

• Nonetheless, market supply-demand balances remain tight. Strong demand growth—fueled by the acceleration of activity in resource-intensive emerging economies—sluggish supply responses, and declining inventories and spare capacity, are likely to keep prices high and volatile.

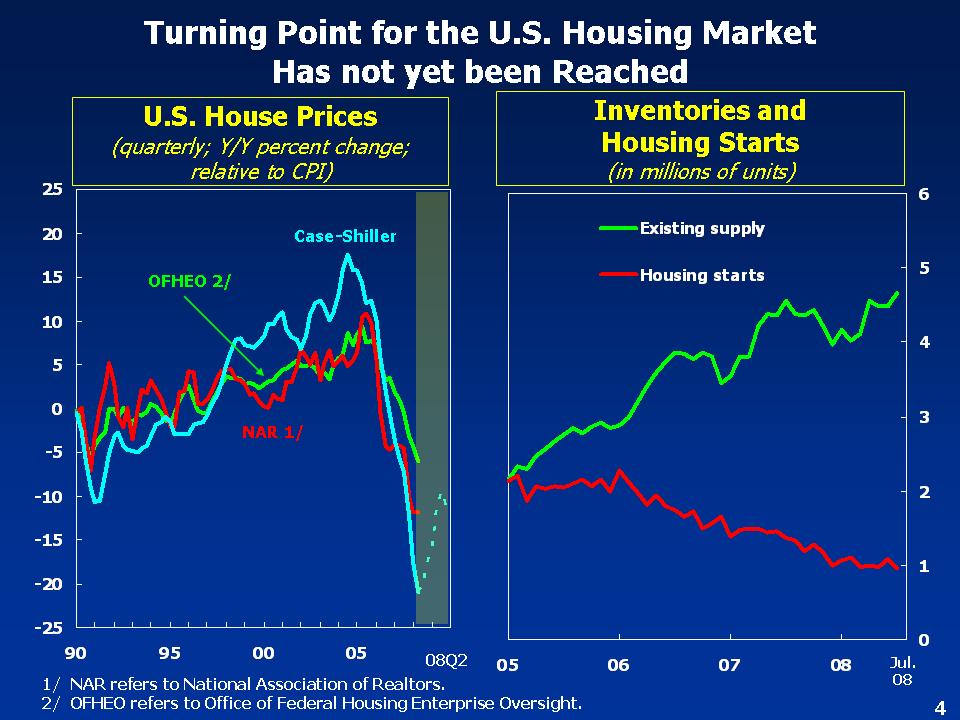

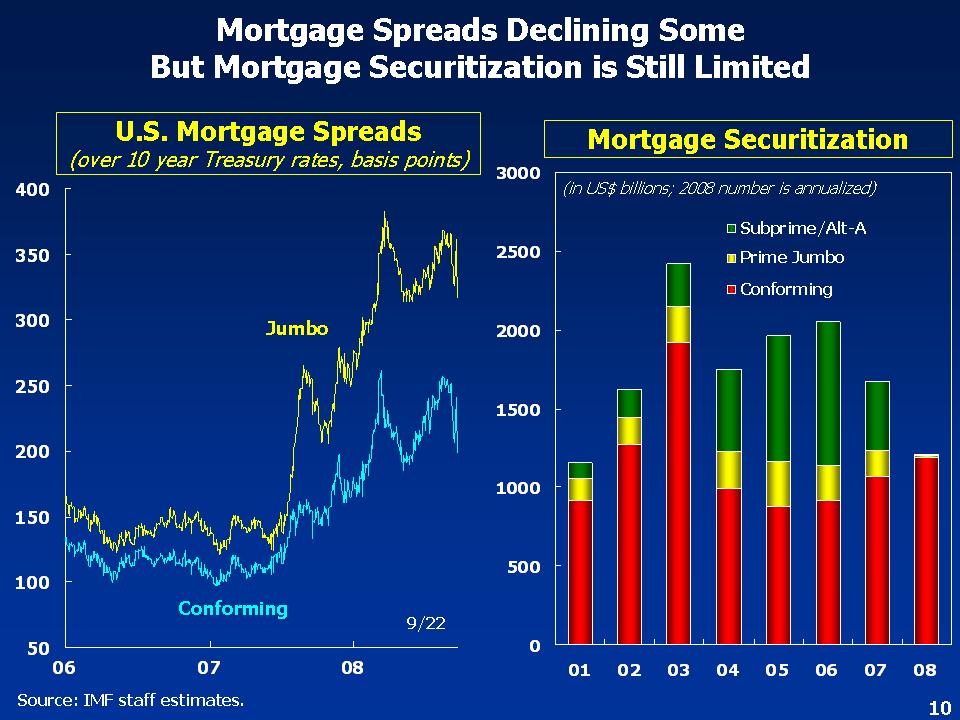

The housing downturn—the epicenter of the slowdown in the United States—is still unfolding. With a large glut of unsold homes, house prices—on a national basis—continue to fall and the negative equity (or level) problem is still growing, although futures data suggest some deceleration in the rate of price decline. As prices fall, however, the collateral value of housing is declining, adding to the financial market pressures. Despite this collateral effect, consumption has held up better than might have been expected, in part because the moderate drop in total US employment has not prevented a modest gain in disposable income, including the impact of the income tax rebates that were distributed at the end of the second quarter.

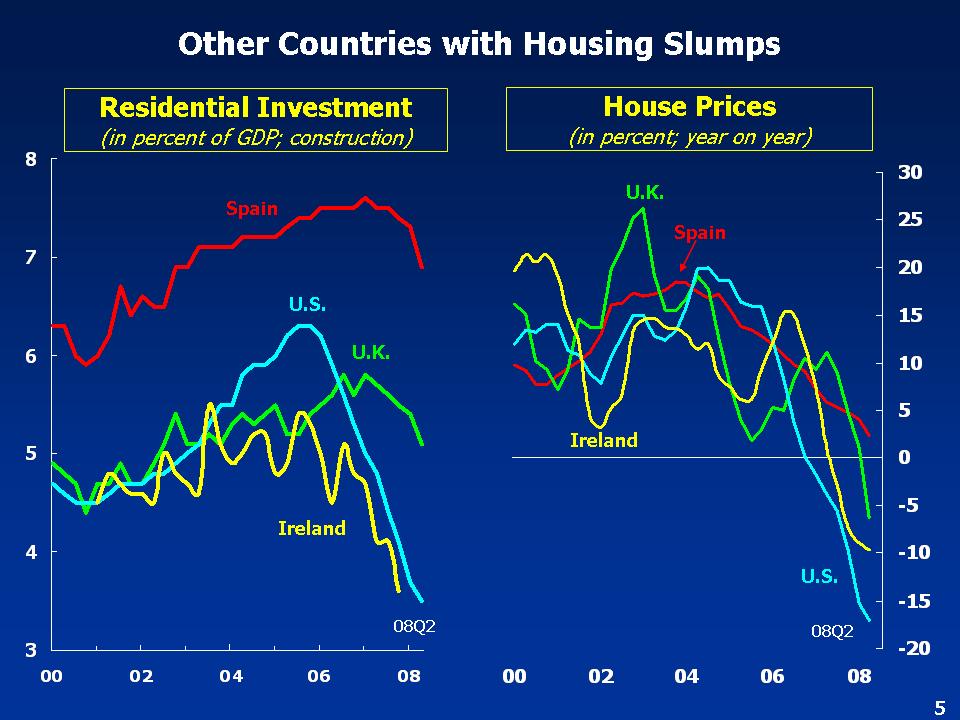

House price declines and sharp drops in residential construction also are underway in some economies outside the United States. As housing markets in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain turn down, concerns about feedback to the financial sector are mounting. Some key mortgage lenders in the United Kingdom are facing increasing losses, and in response policymakers there helped to arrange the sale of the country's fifth largest bank. Moreover, these weakening trends likely have some way to go before they stabilize.

Financial Strains

As is recognized widely, it is the intensified financial crisis that is dominating the near-term global outlook.

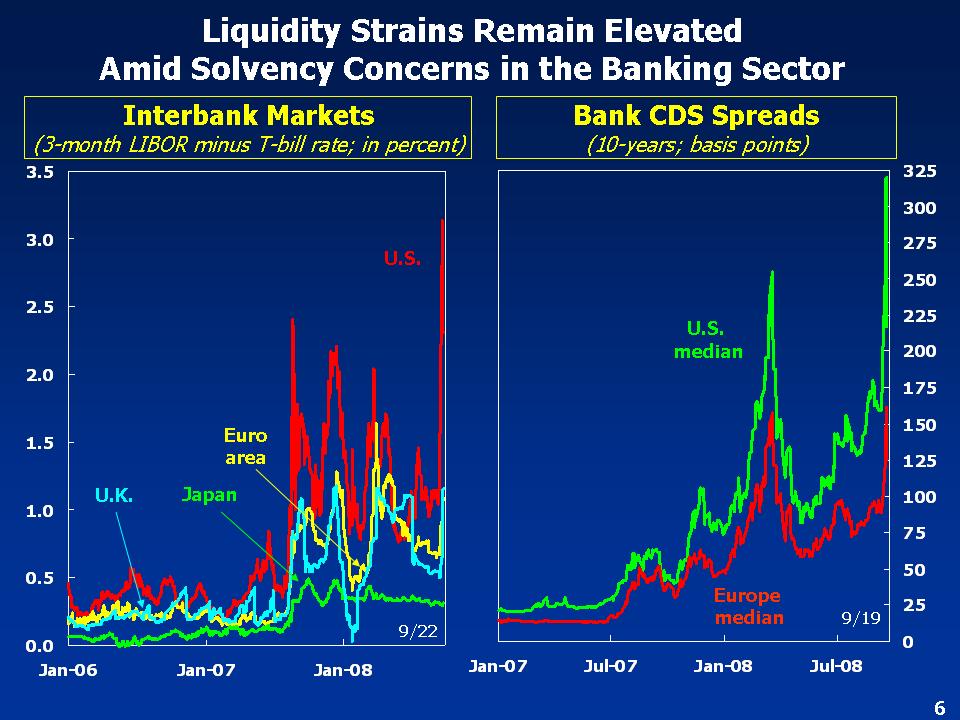

Notwithstanding extraordinary actions by major central banks, interbank spreads have widened sharply, underlining heightened risk aversion and uncertainty. Strains in term-funding markets increasingly reflect not only liquidity but serious credit risks and counterparty concerns. Elevated credit risks reflect the ongoing pressures on bank balance sheets, as well as signs of wider credit deterioration in the context of slower economic growth, particularly in areas exposed to the U.S. mortgage, construction, and commercial real estate markets. As a result, monetary and financial conditions have tightened further. Weaker share prices and wide spreads on mortgage and corporate debt have raised financing costs.

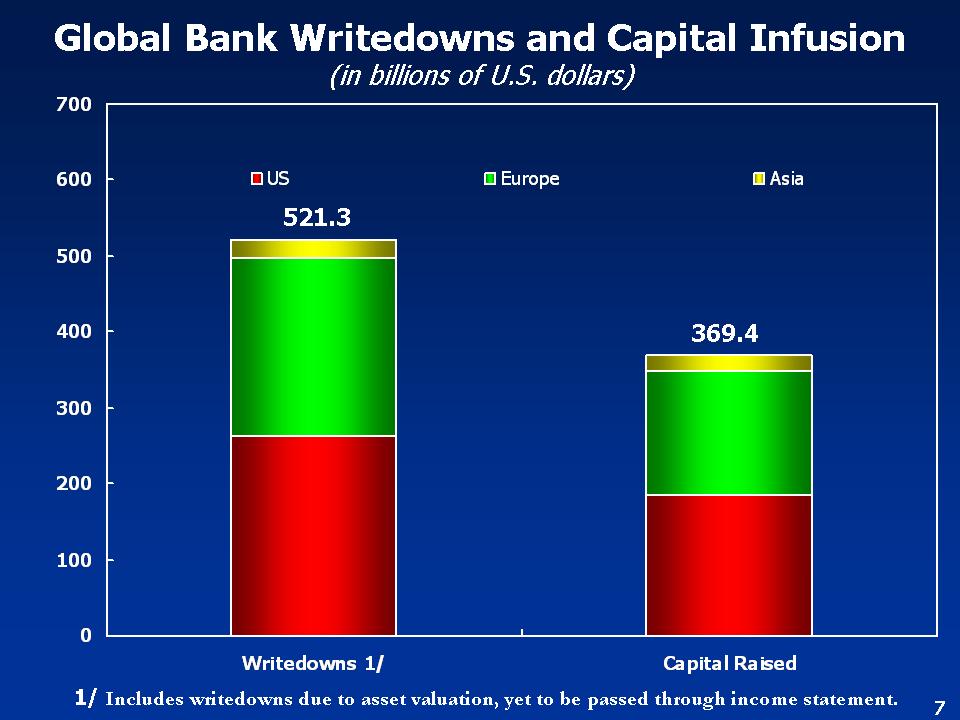

Progress has been made towards balance sheet adjustment, but the task of strengthening financial positions has become much more challenging. In both the United States and in Europe, banks have raised substantial amounts of capital while writing down about $520 billion (largely on U.S. based assets), compared to loss estimates of between $640-735 billion for banks and about $1.3 trillion for the entire global financial system. But the downturn in economic activity, falling share prices, rising funding costs and declining revenues from activities like securitization and leveraged buyouts are making adjustment more difficult. Ongoing deleveraging in the financial sector is likely to weigh on the pace of credit and economic growth for a considerable period of time.

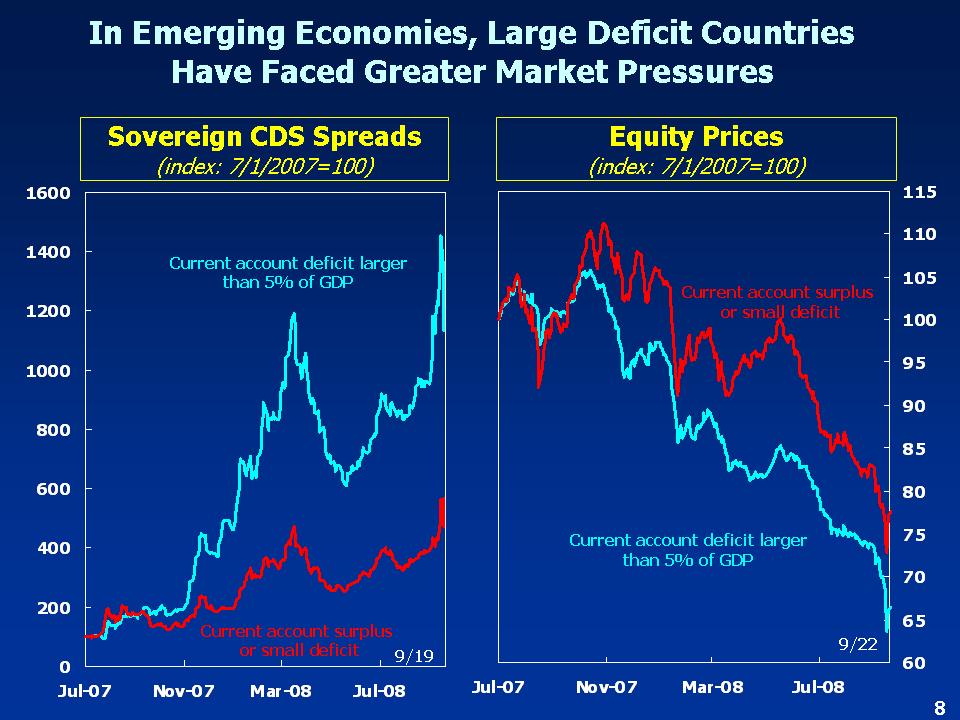

Emerging economies are also now being increasingly affected by the financial crisis. Equity prices have declined sharply and bond spreads have widened. Countries with larger external current account deficits have faced greater market pressures in both credit and equity markets, underscoring their greater vulnerability to spillovers from financial and economic stress in advanced economies.

Global Outlook

Looking forward, four principal factors underpin our view that a serious downturn can be avoided.

First, as noted earlier, oil prices have come down sharply from their highs. Notwithstanding some recent price increases, this is likely to reverse a significant portion of the adverse terms-of-trade effects arising from the more than 60 percent increase in oil prices during 2008 (at the peak) and the erosion in purchasing power and real wages being felt by most advanced economies, as well as emerging economies that are commodity importers.

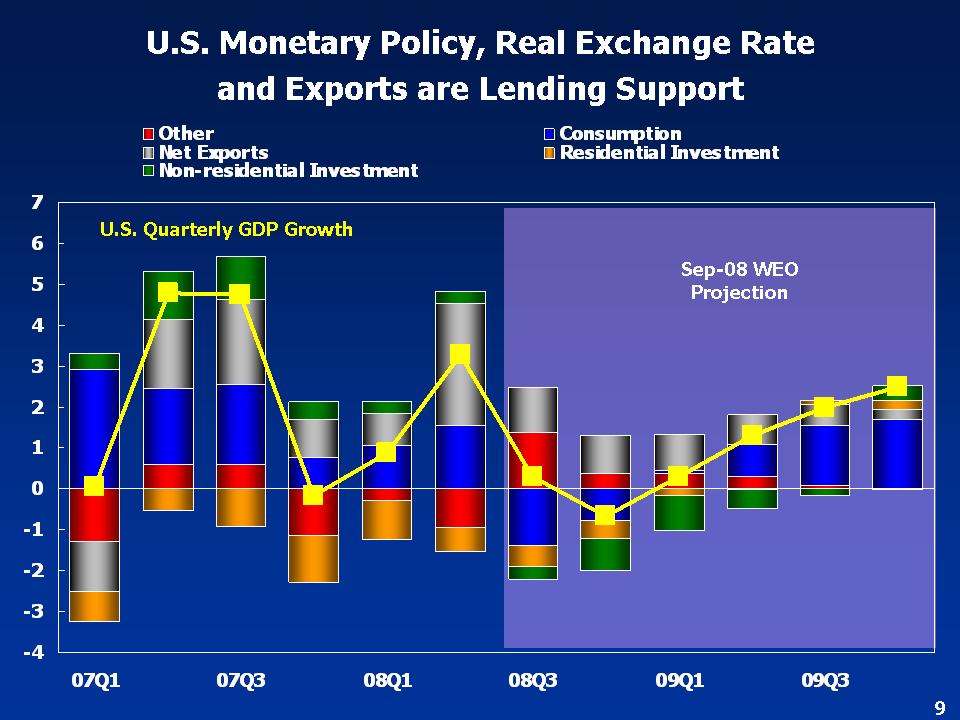

In the United States, if oil prices remain around current levels, the implied boost to real disposable incomes will rival the stimulus provided by the income tax rebates. Indeed, in our projections, we expect a modest rebound in consumption in the United States (and in the euro area) over the course of 2009.

Second, it is not unreasonable to anticipate that the U.S. housing market will find a bottom through the course 2009.

Affordability measures are gradually returning to levels more consistent with past experience, which should support housing demand. U.S. Treasury support for the GSEs, allowing these agencies to expand their balance sheets through 2009, should help in the supply of mortgages, while direct Treasury purchases of the GSEs mortgage-backed securities should help to keep mortgage costs down.

As the decline in home prices begins to level off, we would expect residential investment to find a floor; residential investment has been a considerable drag on overall activity—amounting to ¾ percent of GDP over the past two years.

Stabilization of house prices would also help contain mortgage-related losses in the financial sector.

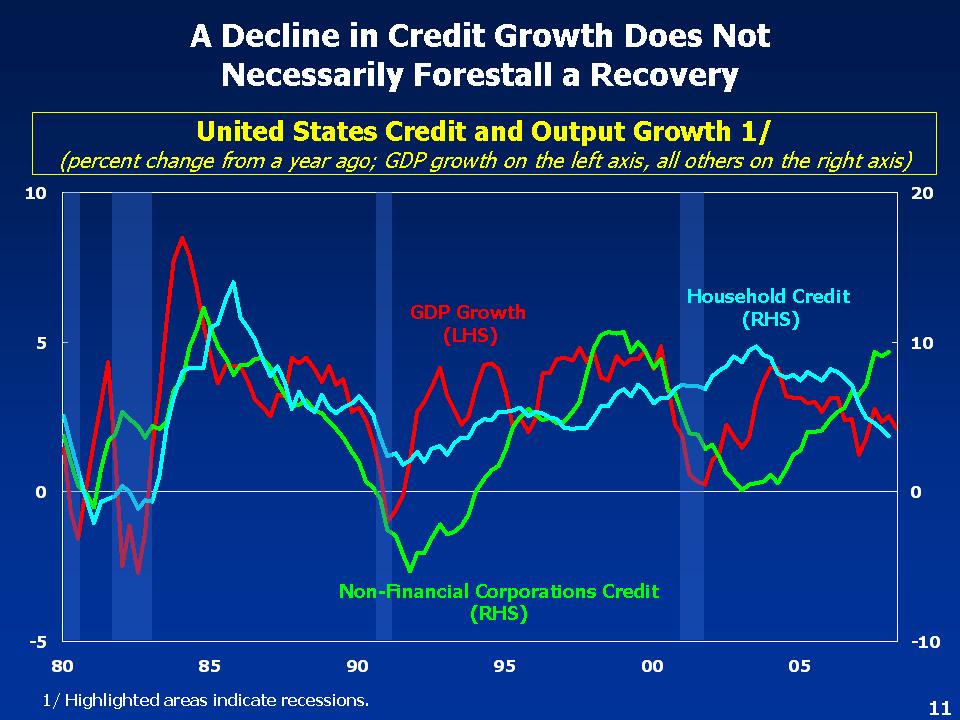

Third, while credit conditions have tightened in both the United States and Europe, growth can continue. Recent IMF analysis suggests that a slowdown in credit provision does not necessarily forestall an economic recovery. In the United States, for example, non-financial corporate balance sheets are relatively healthy. Productivity gains have helped to sustain profits. As in past U.S. downturns, internal funds help buffer against less provision of bank credit and market financing. Time-bound investment tax credits will also encourage corporate capital expenditures in the coming months.

Finally, we expect that relatively resilient domestic demand and growth in emerging economies would support global (and U.S.) growth. While the financial crisis is starting to spill over to emerging markets, strong internal momentum, very large reserves, and generally improved policy frameworks, should help these countries buffer the effects of external financial shocks. This should contribute significantly to global growth, where major emerging economies have taken center stage in recent years.

This should also help reduce global imbalances and support U.S. activity through its net exports, also given the past depreciation of the U.S. dollar. Based on our assessments, in fact, the real multilateral value of the U.S. dollar is much closer to its fundamental value than has been the case in many years.

In this context, however, I would note that the lack of adjustment in the currencies of several economies with inflexible exchange rate regimes and large external surpluses has not been supportive of global adjustment. These relatively faster growing economies—notably China—would benefit from some currency appreciation to help foster more balanced internal growth, relieve domestic price pressures, and, at the same time, support global growth and reduce imbalances.

On balance, we anticipate a further slowdown in global growth before a gradual recovery begins during the coming year . Nonetheless, the challenges facing the global economy and the financial system are formidable, and downside risks to the outlook have risen.

Risks and Policy Challenges

An overarching risk revolves around the potential negative feedback loop between continuing financial market strains and slowing economic activity. Despite aggressive policy actions aimed at alleviating liquidity strains and preventing systemic events, markets remain under severe stress. Beyond systemic events, a major concern is that rising losses, increasing difficulty raising capital, and more aggressive attempts to deleverage balance sheets could imply severe credit contraction, In addition, emerging market economies, that have so far been relatively insulated from the financial turmoil, potentially could be subject to capital flow reversals, with serious implications for economic activity.

The confluence of shocks has made policymaking more difficult, and resolving the financial crisis on a durable basis will require creative solutions across a range of policy instruments. The key challenges to restoring the financial system to full functionality are to insure adequate liquidity provision, to restore damaged balance sheets, and to rebuild capital where needed. An element that makes these policy challenges particularly difficult is that in many markets, the financial sector likely became outsized. Thus, restoring the sector to health will include further consolidation. To put it bluntly, not all institutions can or should be saved. Naturally, monetary and budget policies will be critical in meeting the policy challenges, but it is clear already that these alone will not be adequate to reach the goal of restoring balanced growth. The use of the public sector balance sheet to contain systemic financial risks—a third line of defense—no doubt will continue to be instrumental in addressing the problems.

The first line of defense in sustaining liquidity lies with monetary authorities. Monetary policy can play a critical role in helping individual economies find their footing, but the scope for policy easing ultimately will depend on each country's cyclical position.

In advanced economies, we expect the slowdown in activity to help contain inflation. Given the downside risks to growth and the ongoing strains of the financial crisis in advanced economies outside the United States, there could be scope to lower interest rates (including in the euro area and the United Kingdom) if activity slows and inflation moderates as we project. In addition, central banks have expanded the scope and duration of their liquidity support through rediscounting operations. In several cases, such as the UK's Special Liquidity Scheme, monetary authorities have developed innovative techniques to improve market liquidity.

In many emerging economies, the shifting balance of risks between inflation and growth suggests greater policy scope for countries with moderating inflation and policy credibility to take a "wait and see" approach. That said, inflation risks still remain serious in several countries where growth remains strong and where, given lags in pass-through, food and energy price increases are still in the pipeline and could feed into "second-round" effects. For these countries, monetary policy should still have a tightening bias.

Fiscal policy provides a second line of defense. It has played a role in the United States already and automatic stabilizers are appropriately providing support elsewhere in other advanced economies. In many emerging economies, fiscal policy will have to play a supportive role to monetary policy in helping to bring down inflation.

Fiscal policy is broadly appropriate across the advanced economies, but room for maneuver is limited given the need for medium-term fiscal consolidation in many of these countries. However, support for the financial sector inevitably will involve budgetary costs that must be taken into account in considering policy alternatives.

In emerging economies where inflation remains a problem, fiscal policy should play a more supportive role in restraining demand growth and easing inflation pressures. In particular, greater restraint on spending growth would be helpful as a complement to tighter monetary policy.

Direct intervention is the third line of defense. It has become obvious that direct fiscal intervention is going to be needed in the United States and elsewhere in order to attain the goals of removing distressed assets from financial institutions' balance sheets, and in recapitalizing the financial system where appropriate.

In this context, we welcomed the decisive actions taken by the U.S. authorities to shore up the GSEs, providing crucial support for the U.S. housing market, the banking system, and the broader economy. Over the longer term, a deep restructuring of the GSEs remains essential to restore market discipline, minimize fiscal costs, and limit systemic risks for the future. Ultimately the conflict of private ownership and public policy objectives within the GSEs' former business model needs to be resolved.

The challenge of removing distressed assets from financial institutions' balance sheets currently is front and center, with the US authorities' TARP proposal currently being examined by Congress. The discussions of the TARP have underscored the myriad difficult judgments that have to be made in order to make such a program a success. It is possible that similar challenges will be faced by other advanced economy authorities in the coming months. Earlier this year, the IMF proposed a solution based on long-term swaps of mortgage securities for government bonds. The advantage of such an approach is that it provides near-term relief for bank balance sheets, while ultimately leaving the underlying credit risk with the banks, rather than the taxpayers. In any case, the current discussions also have underscored the importance that moral hazard issues play in direct fiscal intervention in resolving financial sector crises.

More broadly, efforts aimed at alleviating systemic risks, including notably the provision of support to key financial institutions, will require sound judgment. For example, the current market strains to some degree reflect solvency risks. underscoring the need for a systematic and comprehensive approach to deal with distressed assets of failed institutions and in the financial sector more broadly.

In these circumstances, the key is to strike the right balance between safeguarding present financial stability and limiting future moral hazard. This task is by no means an easy one, but the consequences—either in the short- or longer-term—would be severe if the pendulum swings too far in either direction.

The reality of financial globalization means that policy interventions—including the longer-term issues of regulatory and supervisory reforms—need to be globally coherent and consistent in order to be effective. No doubt, new actions will be needed to cope successfully with the near-term challenges. In addition, the issue will have to be addressed eventually of how to prevent excessive risk-taking in the future, without stifling the powerfully positive potential of effective financial markets.

Thank you.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |