World Economic Outlook

New Setbacks, Further Policy Action Needed

July 2012

In the past three months, the global recovery, which was not strong to start with, has shown signs of further weakness. Financial market and sovereign stress in the euro area periphery have ratcheted up, close to end-2011 levels. Growth in a number of major emerging market economies has been lower than forecast. Partly because of a somewhat better-than-expected first quarter, the revised baseline projections in this WEO Update suggest that these developments will only result in a minor setback to the global outlook, with global growth at 3.5 percent in 2012 and 3.9 percent in 2013, marginally lower than in the April 2012 World Economic Outlook. These forecasts, however, are predicated on two important assumptions: that there will be sufficient policy action to allow financial conditions in the euro area periphery to ease gradually and that recent policy easing in emerging market economies will gain traction. Clearly, downside risks continue to loom large, importantly reflecting risks of delayed or insufficient policy action. In Europe, the measures announced at the European Union (EU) leaders' summit in June are steps in the right direction. The very recent, renewed deterioration of sovereign debt markets underscores that timely implementation of these measures, together with further progress on banking and fiscal union, must be a priority. In the United States, avoiding the fiscal cliff, promptly raising the debt ceiling, and developing a medium-term fiscal plan are of the essence. In emerging market economies, policymakers should be ready to cope with trade declines and the high volatility of capital flows.

A better Q1, a worse Q2

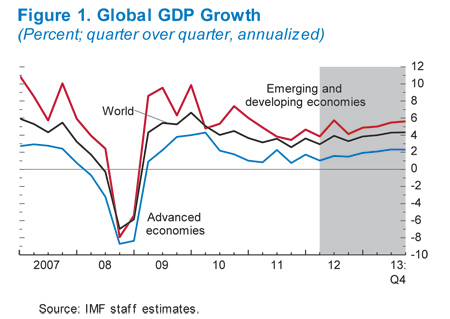

Global growth increased to 3.6 percent (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in the first quarter of 2012, surprising on the upside by some ¼ percentage point compared with the forecasts presented in the April 2012 World Economic Outlook (Figure 1: CSV|PDF, Table 1). The upward surprise was partly due to temporary factors, among them easing financial conditions and recovering confidence in response to the European Central Bank's (ECB's) longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs). Global trade rebounded in parallel with industrial production in the first quarter of 2012, which, in turn, benefited trade-oriented economies, notably Germany and those in Asia. For Asia, growth was also pulled up by a greater-than-anticipated rebound in industrial production, spurred by the restart of supply chains disrupted by the Thai floods in late 2011, and stronger-than-expected domestic demand in Japan.

| Table 1. Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections | |||||||||||

| (Percent change unless noted otherwise) | |||||||||||

| Year over Year | |||||||||||

| Projections | Difference from April 2012 WEO Projections | Q4 over Q4 | |||||||||

| Estimates | Projections | ||||||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2012 | 2013 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |||

| World Output 1/ | 5.3 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.9 | –0.1 | –0.2 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4.1 | ||

| Advanced Economies | 3.2 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.0 | –0.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.2 | ||

| United States | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.3 | –0.1 | –0.1 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.5 | ||

| Euro Area | 1.9 | 1.5 | –0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | –0.2 | 0.7 | –0.2 | 1.2 | ||

| Germany | 3.6 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.4 | –0.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.8 | ||

| France | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.8 | –0.1 | –0.2 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | ||

| Italy | 1.8 | 0.4 | –1.9 | –0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | –0.5 | –1.9 | 0.4 | ||

| Spain | –0.1 | 0.7 | –1.5 | –0.6 | 0.4 | –0.7 | 0.3 | –2.3 | 0.6 | ||

| Japan | 4.4 | –0.7 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.4 | –0.2 | –0.5 | 1.9 | 2.2 | ||

| United Kingdom | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.4 | –0.6 | –0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | ||

| Canada | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.1 | ||

| Other Advanced Economies 2/ | 5.8 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 3.4 | –0.2 | –0.1 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.3 | ||

| Newly Industrialized Asian Economies | 8.5 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 4.2 | –0.6 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 3.6 | ||

| Emerging and Developing Economies 3/ | 7.5 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 5.9 | –0.1 | –0.2 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6.5 | ||

| Central and Eastern Europe | 4.5 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 0.0 | –0.1 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 3.6 | ||

| Commonwealth of Independent States | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 0.0 | –0.1 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 4.5 | ||

| Russia | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 0.0 | –0.1 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 4.8 | ||

| Excluding Russia | 6.0 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | –0.1 | –0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Developing Asia | 9.7 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.5 | –0.3 | –0.4 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 7.6 | ||

| China | 10.4 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 8.5 | –0.2 | –0.3 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 8.4 | ||

| India | 10.8 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 6.5 | –0.7 | –0.7 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.4 | ||

| ASEAN-5 4/ | 7.0 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 0.0 | –0.1 | 2.6 | 7.5 | 6.4 | ||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 6.2 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 4.2 | –0.3 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 5.1 | ||

| Brazil | 7.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 4.6 | –0.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 4.0 | ||

| Mexico | 5.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.2 | ||

| Middle East and North Africa | 5.0 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.3 | –0.1 | 0.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| South Africa | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.3 | –0.1 | –0.1 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.7 | ||

| Memorandum | |||||||||||

| European Union | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | –0.3 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 1.5 | ||

| World Growth Based on Market Exchange Rates | 4.2 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 0.0 | –0.2 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 3.4 | ||

| World Trade Volume (goods and services) | 12.8 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 5.1 | –0.3 | –0.5 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Imports | |||||||||||

| Advanced Economies | 11.5 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Emerging and Developing Economies | 15.3 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 7.0 | –0.6 | –1.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Exports | |||||||||||

| Advanced Economies | 12.2 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 4.3 | 0.0 | –0.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Emerging and Developing Economies | 14.4 | 6.6 | 5.7 | 6.2 | –0.9 | –1.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Commodity Prices (U.S. dollars) | |||||||||||

| Oil 5/ | 27.9 | 31.6 | –2.1 | –7.5 | –12.4 | –3.4 | 20.8 | –7.7 | –2.1 | ||

| Nonfuel (average based on world commodity export weights) | 26.3 | 17.8 | –12.0 | –4.3 | –1.7 | –2.2 | –6.4 | –3.9 | –2.5 | ||

| Consumer Prices | |||||||||||

| Advanced Economies | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.1 | –0.1 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | ||

| Emerging and Developing Economies 3/ | 6.1 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 3.9 | ||

| London Interbank Offered Rate (percent) 6/ | |||||||||||

| On U.S. Dollar Deposits | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| On Euro Deposits | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | –0.1 | –0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| On Japanese Yen Deposits | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | –0.2 | 0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

| Note: These forecasts incorporate information received through Friday, July 6, 2012. Real effective exchange rates are assumed to remain constant at the levels prevailing during May 7–June 4, 2012. When economies are not listed alphabetically, they are ordered on the basis of economic size. The aggregated quarterly data are seasonally adjusted. | |||||||||||

| 1/The quarterly estimates and projections account for 90 percent of the world purchasing-power-parity weights. | |||||||||||

| 2/Excludes the G7 and euro area countries. | |||||||||||

| 3/The quarterly estimates and projections account for approximately 80 percent of the emerging and developing economies. | |||||||||||

| 4/Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. | |||||||||||

| 5/Simple average of prices of U.K. Brent, Dubai, and West Texas Intermediate crude oil. The average price of oil in U.S. dollars a barrel was $104.01 in 2011; the assumed price based on futures markets is $101.80 in 2012 and $94.16 in 2013. | |||||||||||

| 6/Six-month rate for the United States and Japan. Three-month rate for the euro area. | |||||||||||

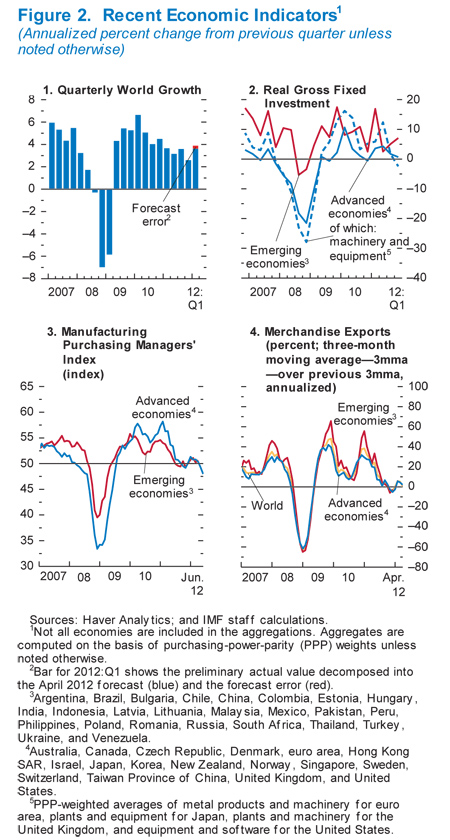

Developments during the second quarter, however, have been worse (Figure 2: CSV|PDF). Relatedly, job creation has been hampered, with unemployment remaining high in many advanced economies, especially among the young in the euro area periphery.

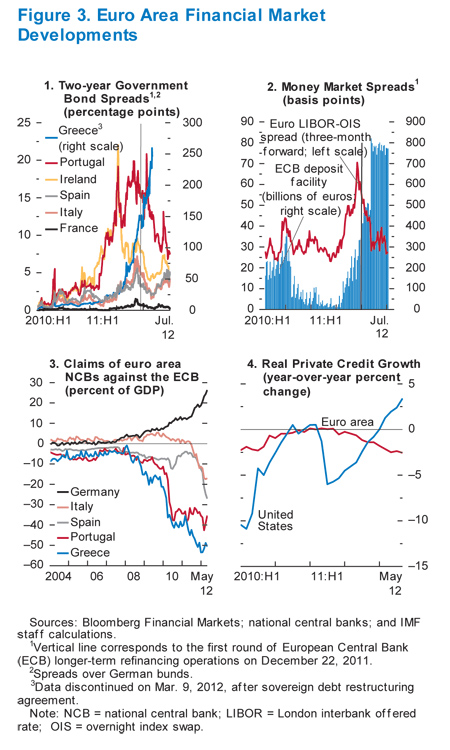

The euro area periphery has been at the epicenter of a further escalation in financial market stress, triggered by increased political and financial uncertainty in Greece, banking sector problems in Spain, and doubts about governments' ability to deliver on fiscal adjustment and reform as well as about the extent of partner countries' willingness to help. Escalating stress in periphery economies has manifested itself along lines familiar from earlier episodes, including capital outflows, a renewed surge in sovereign yields (Figure 3: CSV|PDF), adverse feedback loops between sovereign stresses and banking sector funding problems, increases in Target 2 liabilities of periphery central banks, further bank deleveraging, and contraction in credit to the private sector. The stabilizing effects of the ECB's LTROs in periphery financial markets have thus eroded. On the real side, leading economic indicators presage renewed contraction of activity in the euro area as a whole in the second quarter.

Incoming data for the United States also suggest less robust growth than forecast in April. While distortions to seasonal adjustment and payback from the unusually mild winter explain some of the softening, there also seems to be an underlying loss of momentum. Negative spillovers from the euro area, limited so far, have been partially offset by falling long-term yields due to safe haven flows (see below).

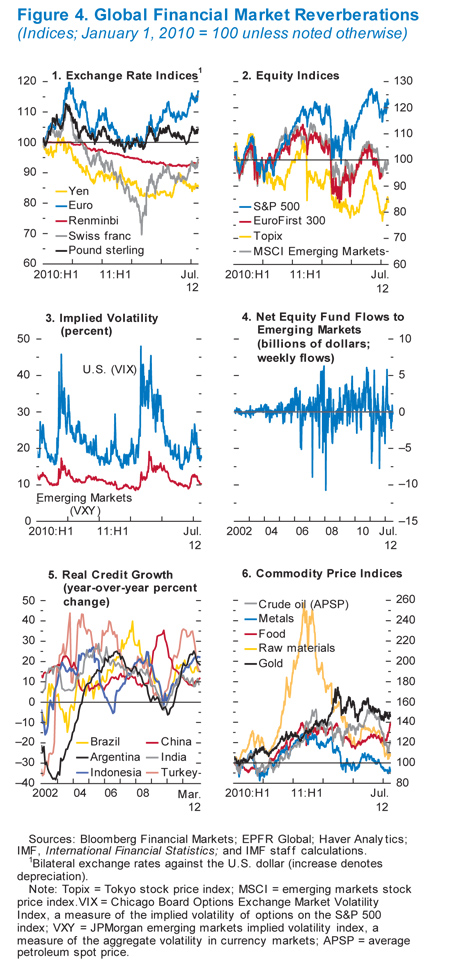

Growth momentum has also slowed in various emerging market economies, notably Brazil, China, and India. This partly reflects a weaker external environment, but domestic demand has also decelerated sharply in response to capacity constraints and policy tightening over the past year. Many emerging market economies have also been hit by increases in investor risk aversion and perceived growth uncertainty, which have led not only to equity price declines, but also to capital outflows and currency depreciation. In global financial markets (Figure 4: CSV|PDF), prices of risky assets declined during much of the second quarter, notably equity prices, while yields on safe haven bonds (Germany, Japan, Switzerland, and the United States) retreated to multidecade lows (see also the July 2012 Global Financial Stability Report Market Update). With some of the capital flows into perceived safe assets occurring within the euro area, the weakening of the euro has been limited. However, sovereign debt markets in the euro area periphery remain unsettled.

Commodity prices have also fallen. Among major commodities, prices of crude oil declined the most in the second quarter—at about $86 a barrel, they are some 25 percent below their mid-March highs—given the combined effects of weaker global demand prospects, easing concerns about Iran-related geopolitical oil supply risks, and continued above-quota production by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) members.

Global growth weak through 2012

The baseline projections in this WEO Update incorporate weaker growth through much of the second half of 2012 in both advanced and key emerging market economies, reflecting the setbacks to the global recovery discussed above. The near-term forecasts are based on the usual assumption of current policies, with two important qualifications:

- The projections assume that financial conditions in the euro area periphery will gradually ease through 2013 from the levels reached in June this year, predicated on the assumption that policymakers will follow up on the positive decisions agreed upon at the June EU leaders' summit and will take action as needed if conditions deteriorate further.

- The projections also assume that current legislation in the United States, which implies a mandatory sharp reduction in the federal budget deficit—the so-called fiscal cliff—will be modified so as to avoid a large fiscal contraction in the near term.

Overall, global growth is projected to moderate to 3.5 percent in 2012 and 3.9 percent in 2013, some 0.1 and 0.2 percentage point, respectively, lower than forecast in the April 2012 WEO (Table 1). In view of a stronger-than-expected first quarter outcome, weaker global growth in the second half of 2012 will primarily affect annual growth in 2013 through base effects.

Growth in advanced economies is projected to expand by 1.4 percent in 2012 and 1.9 percent in 2013, a downward revision of 0.2 percentage point for 2013 relative to the April 2012 WEO. The downward revision mostly reflects weaker activity in the euro area, especially in the periphery economies, where the dampening effects from uncertainty and tighter financial conditions will be strongest. Owing mainly to negative spillovers, including from uncertainty, growth in most other advanced economies will also be slightly weaker, although lower oil prices will likely dampen these adverse effects.

Growth in emerging and developing economies will moderate to 5.6 percent in 2012 before picking up to 5.9 percent in 2013, a downward revision of 0.1 and 0.2 percentage point in 2012 and 2013, respectively, relative to the April 2012 WEO. In the near term, activity in many emerging market economies is expected to be supported by the policy easing that began in late 2011 or early 2012 and, in net fuel importers, by lower oil prices, depending on the extent of the pass-through to domestic retail prices (which is often incomplete).

Growth is projected to remain relatively weaker than in 2011 in regions connected more closely with the euro area (Central and Eastern Europe in particular). In contrast with the broad trends, growth in the Middle East and North Africa will be stronger in 2012–13 relative to last year, as key oil exporters continue to boost oil production and domestic demand while activity in Libya is rebounding rapidly after the unrest in 2011. Similarly, growth in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to remain robust in 2012–13, helped by the region's relative insulation from external financial shocks, and revisions to the growth outlook since the April 2012 WEO are modest.

Global consumer price inflation is projected to ease as demand softens and commodity prices recede. Overall, headline inflation is expected to slip from 4½ percent in the last quarter of 2011 to 3–3½ percent in 2012–13.

The global recovery remains at risk

Downside risks to this weaker global outlook continue to loom large. The most immediate risk is still that delayed or insufficient policy action will further escalate the euro area crisis. In this regard, agreements reached at the EU leaders' summit are steps in the right direction. But further steps are needed, notwithstanding high implementation hurdles, as underscored by the very recent deterioration in sovereign debt markets. The situation in the euro area crisis economies will likely remain precarious until all policy action needed for a resolution of the crisis has been taken (see below). Other downside risks relate to fiscal policy in other advanced economies:

- In the short term, the main risk relates to the possibility of excessive fiscal tightening in the United States, given recent political gridlock. In the extreme, if policymakers fail to reach consensus on extending some temporary tax cuts and reversing deep automatic spending cuts, the U.S. structural fiscal deficit could decline by more than 4 percentage points of GDP in 2013. U.S. growth would then stall next year, with significant spillovers to the rest of the world. Moreover, delays in raising the federal debt ceiling could increase risks of financial market disruptions and a loss in consumer and business confidence.

- Another risk arises from insufficient progress in developing credible plans for medium-term fiscal consolidation in the United States and Japan—the flight to safety in global bond markets currently mitigates this risk. In the absence of policy action, medium-term public debt ratios would continue to move along unsustainable trajectories. As the global recovery advances, a lack of progress could trigger sharply higher sovereign borrowing costs in the United States and Japan as well as turbulence in the global bond and currency markets.

Downside risks to growth in emerging market and developing economies seem primarily related to external factors in the near term. The slowdown in emerging market growth since mid-2011 has been partly the result of policy tightening in response to signs of overheating. But policies have been eased since, and this easing should gain traction in the second half of 2012.

Nevertheless, concerns remain that potential growth in emerging market economies might be lower than expected. Growth in these economies has been above historical trends over the past decade or so, supported in part by financial deepening and rapid credit growth, which may well have generated overly optimistic expectations about potential growth. As a result, growth in emerging market economies could be lower than expected over the medium term, with a correspondingly smaller contribution to global growth. Also of concern are risks to financial stability after years of rapid credit growth in the current environment of weaker global growth, elevated risk aversion, and some signs of domestic strain. Among low-income countries, those dependent on aid face risks of lower-than-expected budget support from advanced economies, while commodity exporters are vulnerable to further erosion of commodity prices. In the medium term, there are tail risks of a hard landing in China, where investment spending could slow more sharply given overcapacity in a number of sectors.

On the positive side, oil price risks have abated in recent months, reflecting the interaction of changes in prospective market conditions and perceived geopolitical risks. Supply conditions have improved due to increased production in Saudi Arabia and other key exporters, while demand prospects have weakened and are subject to downside risks. With geopolitical risks to oil supply widely perceived to have declined, risks to oil price projections appear more evenly balanced now, while those around prices of non-oil commodities tilt downward.

Crisis management remains the top priority

The utmost priority is to resolve the crisis in the euro area. The recent agreements, if implemented in full, will help to break the adverse links between sovereigns and banks and create a banking union. In particular, once the agreed-upon single supervisory mechanism for euro area banks is established, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) would be able to recapitalize banks directly. Moreover, ESM assistance will not carry seniority status for Spain—an important step to support market confidence. In addition, the leaders re-affirmed a willingness to consider secondary purchases of sovereign bonds by the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the ESM.

But these measures must be complemented by more progress on banking and fiscal union. In addition, the periphery countries need to remain on track with their policy reform commitments, for which they need a supportive financial and growth environment that must be facilitated by the ECB and other euro-area-level facilities. These tasks require policy measures in several areas:

- A credible commitment toward a robust and complete monetary union. By setting in motion a process toward a unified supervisory framework, the European summit put in place the first building block of a banking union. But other necessary elements, including a pan-European deposit insurance guarantee scheme and bank resolution mechanism with common backstops, need to be added. In the shorter term, timely implementation will be essential, including through the ratification of the ESM by all members. In addition, these steps would usefully be complemented by plans for fiscal integration, as anticipated in the report of the “Four Presidents” submitted to the summit.

- The viability of the monetary union must also be supported by wide-ranging structural reforms throughout the euro area to raise growth and resolve intra-area current account imbalances.

- Demand support and crisis management are essential in the short term to cushion the impact of the region's adjustment efforts and maintain orderly market conditions (as assumed in the baseline projections).

- There is room for monetary policy in the euro area to ease further. In addition, the ECB should ensure that its monetary support is transmitted effectively across the region and should continue to provide ample liquidity support to banks under sufficiently lenient conditions. This might require nonstandard measures, such as reactivation of the Securities Market Programme, additional LTROs with lower collateral requirements, or the introduction of QE-style asset purchases.

- Fiscal consolidation plans in the euro area must be implemented. In general, attention should be paid to meeting structural fiscal targets, rather than nominal targets that will likely be affected by economic conditions. Automatic stabilizers should thus be allowed to operate fully in economies not subject to market pressure. Considering the large downside risks, economies with limited fiscal vulnerability should stand ready to implement fiscal contingency measures if such risks materialize.

In other major advanced economies, monetary policy also needs to respond effectively, including with further unconventional measures, to a much weaker near-term environment that will dampen price pressures. In view of somewhat weaker global growth, automatic stabilizers should be allowed to operate fully, while fiscal consolidation plans might need to be recalibrated if large downside risks materialize (see the July 2012 Fiscal Monitor Update). In the United States, it will be critical to reach transparent, bipartisan agreements to avoid a fiscal cliff in the near term and to raise the federal debt ceiling well ahead of the deadline (which will most likely be early in 2013). At the same time, both the United States and Japan need more credible plans to put medium-term government debt on a downward track. In Japan, a full Diet approval—after passage in the Lower House—of a gradual increase in the consumption tax rate is essential to maintain confidence in the authorities' resolve to put public debt on a sustainable trajectory.

In emerging and developing economies, policymakers should stand ready to adjust policies, given spillovers from weaker advanced economy prospects and slowing export growth and volatile capital flows. That said, the need for and the nature of the desirable policy response vary considerably across emerging market economies because of differences in their cyclical positions. In some, recent growth declines have primarily reflected normalization to trend, and policies must thus avoid rekindling overheating pressures, with due consideration of risks that potential growth could be lower than expected. However, in economies where inflation and credit pressures have already eased credibly or where inflation expectations remain firmly anchored, further cuts in policy rates could be considered to help alleviate weakening economic conditions. In economies where inflation and credit pressures have not eased significantly, targeted measures could be considered should bank liquidity or funding pressures arise in the context of the current unsettled global financial environment. Economies with sustainable public finances and market financing at sustainable rates should allow automatic stabilizers to play fully, while those with large fiscal and external surpluses could consider fiscal support. Finally, with growth slowing and after many years of rapid credit growth, enhanced risk-based prudential regulation and supervision and macroprudential measures that address financial risks should take top priority.