World Economic Outlook

Growing Pains

July 2013

Global growth is projected to remain subdued at slightly above 3 percent in 2013, the same as in 2012. This is less than forecast in the April 2013 World Economic Outlook (WEO), driven to a large extent by appreciably weaker domestic demand and slower growth in several key emerging market economies, as well as a more protracted recession in the euro area. Downside risks to global growth prospects still dominate: while old risks remain, new risks have emerged, including the possibility of a longer growth slowdown in emerging market economies, especially given risks of lower potential growth, slowing credit, and possibly tighter financial conditions if the anticipated unwinding of monetary policy stimulus in the United States leads to sustained capital flow reversals. Stronger global growth will require additional policy action. Specifically, major advanced economies should maintain a supportive macroeconomic policy mix, combined with credible plans for reaching medium-term debt sustainability and reforms to restore balance sheets and credit channels. Many emerging market and developing economies face a tradeoff between macroeconomic policies to support weak activity and those to contain capital outflows. Macroprudential and structural reforms can help make this tradeoff less stark.

Financial market volatility increased globally in May and June after a period of calm since last summer. In advanced economies, longer-term interest rate and financial market volatility have risen. Peripheral euro area sovereign spreads have widened again after a period of sustained declines. Emerging market economies have generally been hit hardest, as recent increases in advanced economy interest rates and asset price volatility, combined with weaker domestic activity (see below) have led to some capital outflows, equity price declines, rising local yields, and currency depreciation.

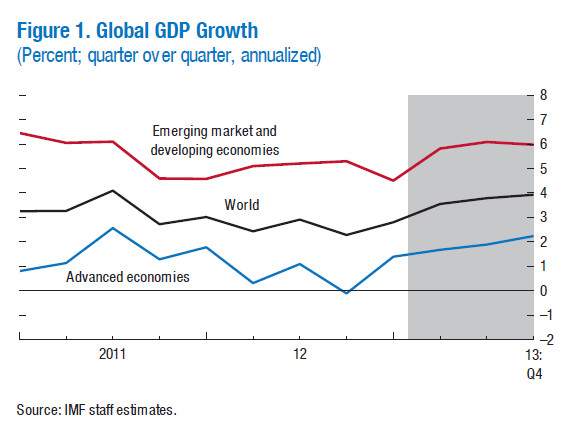

Global growth increased only slightly from an annualized rate of 2½ percent in the second half of 2012 to 2¾ percent in the first quarter of 2013 (Figure 1): CSV, instead of accelerating further as expected at the time of the April 2013 WEO. The underperformance was due to three factors. First, continuing growth disappointments in major emerging market economies, reflecting, to varying degrees, infrastructure bottlenecks and other capacity constraints, slower external demand growth, lower commodity prices, financial stability concerns, and, in some cases, weaker policy support. Second, a deeper recession in the euro area, as low demand, depressed confidence, and weak balance sheets interacted to exacerbate the effects on growth and the impact of tight fiscal and financial conditions. Third, the U.S. economy expanded at a weaker pace, as stronger fiscal contraction weighed on improving private demand. By contrast, growth was stronger than expected in Japan, driven by consumption and net exports—the latter helped by the 20 percent depreciation of the yen (in real effective terms) since late 2012.

Turning to forecasts, growth in the United States is projected to rise from 1¾ percent in 2013 to 2¾ percent in 2014 (Table 1). The projections assume that the sequestration will remain in place until 2014, longer than previously projected, although the pace of fiscal consolidation will still slow. Private demand should remain solid, given rising household wealth owing to the housing recovery, and still supportive financial conditions.

In Japan, growth will average 2 percent in 2013, moderating to about 1¼ percent in 2014. The stronger forecast for 2013 than previously projected reflects the effects of recent accommodative policies on confidence and private demand, while the somewhat softer forecast for 2014 reflects the weaker global environment.

The euro area will remain in recession in 2013, with activity contracting by over ½ percent. Growth will rise to just under 1 percent in 2014, weaker than previously projected, in part due to the persistent effects of the constraints discussed above and the expected delays in policy implementation in key areas, but also due to base effects from the delayed recovery in 2013.

| Table 1. Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections | |||||||||||||

| (Percent change unless noted otherwise) | |||||||||||||

| Year over Year | |||||||||||||

| Difference from April 2013 WEO Published | Q4 over Q4 | ||||||||||||

| Projections | Estimates | Projections | |||||||||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||||

|

World Output 1/ |

3.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.8 | –0.2 | –0.2 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 3.7 | ||||

| Advanced Economies | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.1 | –0.1 | –0.2 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 2.2 | ||||

|

|

United States | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.7 | –0.2 | –0.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 | |||

|

|

Euro Area | 1.5 | –0.6 | –0.6 | 0.9 | –0.2 | –0.1 | –1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | |||

|

Germany | 3.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.3 | –0.3 | –0.1 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | |||

|

|

France | 2.0 | 0.0 | –0.2 | 0.8 | –0.1 | 0.0 | –0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | |||

|

|

Italy | 0.4 | –2.4 | –1.8 | 0.7 | –0.3 | 0.2 | –2.8 | –0.9 | 1.4 | |||

|

|

Spain | 0.4 | –1.4 | –1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | –0.7 | –1.9 | –0.7 | 0.0 | |||

|

|

Japan | –0.6 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.5 | –0.3 | 0.4 | 3.5 | 0.2 | |||

|

|

United Kingdom | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.7 | |||

|

|

Canada | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.2 | –0.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.4 | |||

| Other Advanced Economies 2/ | 3.3 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 3.3 | –0.1 | –0.1 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | ||||

|

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies 3/ | 6.2 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | –0.3 | –0.3 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |||

|

|

Central and Eastern Europe | 5.4 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 3.6 | 2.5 | |||

|

|

Commonwealth of Independent States | 4.8 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.6 | –0.6 | –0.4 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 2.9 | |||

|

|

Russia | 4.3 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 3.3 | –0.9 | –0.5 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 2.5 | |||

|

|

Excluding Russia | 6.1 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 0.0 | –0.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

|

Developing Asia | 7.8 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.0 | –0.3 | –0.3 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 7.0 | |||

|

|

China | 9.3 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.7 | –0.3 | –0.6 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.6 | |||

|

|

India 4/ | 6.3 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 6.3 | –0.2 | –0.1 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 6.6 | |||

|

|

ASEAN-5 5/ | 4.5 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 5.7 | –0.3 | 0.2 | 9.1 | 5.5 | 5.1 | |||

|

|

Latin America and the Caribbean | 4.6 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | –0.4 | –0.5 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.5 | |||

|

|

Brazil | 2.7 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 3.2 | –0.5 | –0.8 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 3.5 | |||

|

|

Mexico | 3.9 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 3.2 | –0.5 | –0.2 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 2.4 | |||

|

|

Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 3.7 | –0.1 | 0.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa | 5.4 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.9 | –0.4 | –0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

|

South Africa | 3.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.9 | –0.8 | –0.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.0 | |||

|

|

Memorandum | ||||||||||||

|

|

European Union | 1.7 | –0.2 | –0.1 | 1.2 | –0.1 | –0.1 | –0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 | |||

|

|

Middle East and North Africa | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 3.7 | –0.1 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

|

World Growth Based on Market Exchange Rates | 2.9 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | –0.1 | –0.2 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.1 | |||

|

World Trade Volume (goods and services) |

6.0 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 5.4 | –0.5 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||||

|

Imports |

|||||||||||||

|

|

Advanced Economies | 4.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 4.3 | –0.8 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies | 8.7 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.3 | –0.2 | 0.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

Exports |

|||||||||||||

|

|

Advanced Economies | 5.6 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 4.7 | –0.4 | 0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies | 6.4 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 6.3 | –0.5 | –0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | |||

|

Commodity Prices (U.S. dollars) |

|||||||||||||

|

Oil 6/ |

31.6 | 1.0 | –4.7 | –4.7 | –2.4 | 0.2 | –1.2 | –4.1 | –3.8 | ||||

|

Nonfuel (average based on world commodity export weights) |

17.9 | –9.9 | –1.8 | –4.3 | –0.9 | 0.0 | 1.2 | –4.5 | –2.3 | ||||

|

Consumer Prices |

|||||||||||||

|

Advanced Economies |

2.7 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.9 | –0.1 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.1 | ||||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies 3/ |

7.1 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 0.1 | –0.1 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 4.9 | ||||

|

London Interbank Offered Rate (percent) 7/ |

|||||||||||||

|

On U.S. Dollar Deposits |

0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||||

|

On Euro Deposits |

1.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | –0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||||

|

On Japanese Yen Deposits |

0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||||

|

Note: Real effective exchange rates are assumed to remain constant at the levels prevailing during May 6–June 3, 2013. When economies are not listed alphabetically, they are ordered on the basis of economic size. The aggregated quarterly data are seasonally adjusted. 1/ The quarterly estimates and projections account for 90 percent of the world purchasing-power-parity weights. 2/ Excludes the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, United States) and euro area countries. 3/ The quarterly estimates and projections account for approximately 80 percent of the emerging market and developing economies. 4/ For India, all data and forecasts (quarterly and annual) are presented on a fiscal year basis in the July 2013 WEO, whereas data were presented on a calendar year basis in the April 2013 WEO. However, the difference between the April 2013 WEO and current 2013–14 growth projections for India was adjusted to be on a fiscal year basis. 5/ Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. 6/ Simple average of prices of U.K. Brent, Dubai Fateh, and West Texas Intermediate crude oil. The average price of oil in U.S. dollars a barrel was $105.01 in 2012; the assumed price based on futures markets is $100.09 in 2013 and $95.36 in 2014. 7/ Six-month rate for the United States and Japan. Three-month rate for the euro area. | |||||||||||||

At 5 percent in 2013 and about 5½ percent in 2014, growth in emerging market and developing economies is now expected to evolve at a more moderate pace, some ¼ percentage points slower than in the April 2013 WEO. This embodies weaker prospects across all regions. In China, growth will average 7¾ percent in 2013-14, ¼ and ½ percentage points lower in 2013 and 2014, respectively, than the April 2013 forecast. Forecasts for the remaining BRICS have been revised down as well, by ¼ to ¾ percentage points. The outlook for many commodity exporters (including those among the BRICS) has also deteriorated due to lower commodity prices. Growth in sub-Saharan Africa will be weaker, as some of its largest economies (Nigeria, South Africa) struggle with domestic problems and weaker external demand. Growth in some economies in the Middle East and North Africa remains weak because of difficult political and economic transitions.

In sum, global growth will recover from slightly above 3 percent in 2013 to 3¾ percent in 2014, some ¼ percent weaker for both years than the April 2013 projections.

Downside risks, old and new, still dominate the outlook. Although imminent tail risks in advanced economies have diminished, additional measures will be needed to keep them at bay, including timely increases in the U.S. debt ceiling and continued “do what it takes” action by the euro area authorities to avoid a sharp deterioration in financial conditions. In contrast, risks of a longer growth slowdown in emerging market economies have now increased, due to protracted effects of domestic capacity constraints, slowing credit growth, and weak external conditions.

The forecasts assume that the recent rise in financial market volatility and the associated yield increases will partly reverse, as they largely reflect a one-off repricing of risk due to the changing growth outlook for emerging market economies and temporary uncertainty about the exit from monetary policy stimulus in the United States. However, if underlying vulnerabilities lead to additional portfolio shifts, further yield increases, and continued higher volatility, the result could be sustained capital flow reversals and lower growth in emerging economies.

Policies to Generate Strong Growth

Weaker growth prospects and new risks raise new challenges to global growth and employment, and global rebalancing. Policymakers everywhere need to increase efforts to ensure robust growth.

As stressed in previous WEO reports, key advanced economies should pursue a policy mix that supports near-term growth, anchored by credible plans for medium-term public debt sustainability. This would also allow for more gradual near-term fiscal adjustment. With low inflation and sizable economic slack, monetary policy stimulus should continue until the recovery is well established. Potential adverse side-effects should be contained with regulatory and macroprudential policies. Clear communication on the eventual exit from monetary stimulus will help reduce volatility in global financial markets. Further progress in financial sector restructuring and reform is needed to recapitalize and restructure bank balance sheets and improve monetary policy transmission.

In the euro area, a bank asset review should identify problem assets and quantify capital needs, supported by ESM direct recapitalization where appropriate. Building on recent agreements, policymakers should also make progress to a fuller banking union, including through a strong Single Resolution Mechanism. Policies to reduce financial market fragmentation, support demand, and reform product and labor markets are also crucial for stronger growth and job creation.

Cyclical positions and vulnerabilities vary across emerging market and developing economies, but prospects of monetary policy normalization in the United States and a potential capital flow reversal have heightened some policy trade-offs. Risks of lower-than-expected potential output in some economies suggest that there may be less fiscal policy space than previously estimated. Monetary easing can be the first line of defense against downside risks, as inflation is generally expected to moderate in most economies. However, real policy rates are low already, and capital outflows and price effects from exchange rate depreciation may also constrain further easing. With weaker growth prospects and potential legacy problems from a prolonged period of rapid credit growth, the policy framework must be ready to handle possible increases in financial stability risks. While macroeconomic policies can support these efforts, the main instruments should be regulatory oversight and macroprudential policies.

Finally, the above measures need to be supported by structural reforms across all major economies to lift global growth and support global rebalancing. As before, this implies measures to sustainably raise consumption (China) and investment (Germany) in surplus economies, as well as measures that improve competitiveness in deficit economies.