Scaling Up the Single Market to Boost Productivity

November 14, 2024

Thank you, Boris, for the kind welcome, and the European Central Bank for hosting us again today for the launch of the Regional Economic Outlook focusing on productivity.

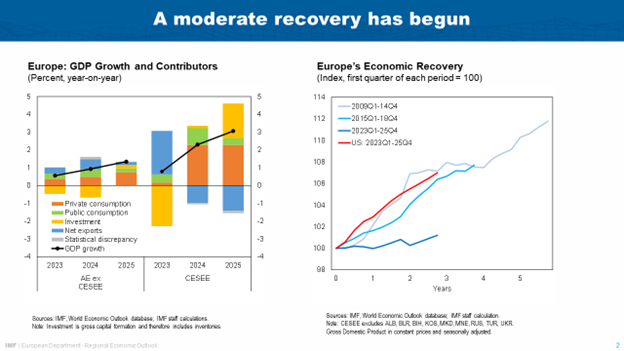

Europe’s long-anticipated recovery following a sequence of unprecedented shocks has begun, with an orderly disinflation process well underway in many countries.

Yet, both in the short- and the medium-term, we see Europe’s economic trajectory falling short of its true potential. Uncertainty has been causing households to refrain from spending and firms to scale back investment plans. Together, the increased caution makes for a comparatively tepid short-term recovery. And looking beyond the next few quarters, prospects are weighed down by persistently low productivity growth. Europe’s innovation efforts are falling short, and the productivity gap vis-à-vis the global frontier is only widening.

I want to argue today that Europe can do much better, and must do much better. Drawing on the analyses in the Regional Economic Outlook Note published this morning, I will outline the bottlenecks that hamper European firms’ growth and innovation. I will then highlight the necessary steps Europe must take to remove these obstacles and lift living standards.

The key message we are having today is a very encouraging one: a productivity revival is in Europe’s own hands. What it will take is a deeper single market – and, given the shock-prone world we are living in, integrating more fully within the single market is key to strengthening economic resilience.

European policy makers are aware of the need to come together, and with a new Commission focused on strengthening Europe’s economic footing, there is a window of opportunity that Europe cannot afford to miss. The world has changed, Europe has to step up.

Europe is Recovering at a Modest Pace

To place the discussion on productivity in context, let me begin with an overview of our latest growth outlook.

A recovery is underway. The preliminary data for growth in the third quarter of this year show that the euro area expanded by 0.4 and the EU by 0.3 percent, on a quarter-on-quarter basis. Our baseline outlook is for a continued modest increase in growth into 2025 for both advanced European economies and the Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe region. A rebound in private consumption and investment will be the key drivers, thanks to steadily growing disposable incomes and easing of financial tightness.

However, the pace of recovery is far from impressive. It lags significantly behind Europe’s previous post-crisis recoveries and the strong rebound seen in the U.S.

Headwinds Ahead

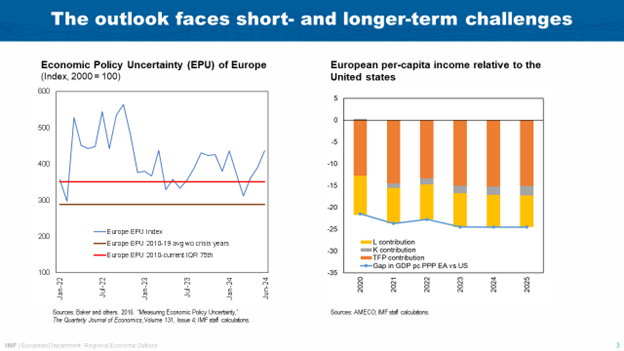

A critical factor explaining this tepid recovery in the near-term is high uncertainty. Since the beginning of this year, geoeconomic tensions have escalated, and uncertainty about the direction of both domestic and trade policies has risen. This has made households reluctant to spend their savings and firms reluctant to invest.

The relatively weak recovery adds to the bigger backdrop of concerns that Europe’s growth is falling behind. Currently, Europe’s per capita income is about 30 percent lower than that of the U.S., largely because of a sizable productivity gap that opened up in the last two and a half decades. With the inevitable headwinds from aging, higher productivity is truly the only game in town to sustainably higher growth.

Europe’s Leading Firms are Slipping from the Global Frontier

In our latest Regional Economic Outlook, we uncover the firm-level roots of Europe’s productivity shortfall. The picture is sobering as deficiencies cut across firms’ lifecycles, affecting both mature leading companies and younger enterprises.

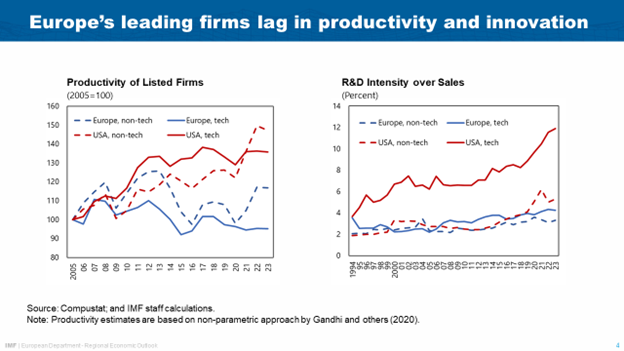

Europe’s large leading firms are trailing their U.S. counterparts in terms of productivity growth. This divergence is broad-based, spanning both the tech and the non-tech sectors. Over the last two decades, the annualized productivity growth of Europe’s non-tech firms was of 0.9 percent, compared to 2.6 percent in the U.S. The divergence, if anything, has been slightly more pronounced among tech firms: European listed firms’ productivity in these sectors has declined at an annualized rate of 0.3 percent since the mid-2000s, compared to an annualized growth of 1.5 percent among U.S. firms.

The productivity divergence comes hand-in-hand with a widening gap in innovation efforts, especially in the tech sector. R&D expenditures of European tech firms have hovered around 3 to 4 percent of the sales in recent years, while they have tripled in the U.S. reaching around 12 percent of sales in 2023.

A Broader Lack of Dynamism Permeates Europe’s Business Landscape

Looking beyond the leading firms, Europe suffers a broader lack of business dynamism.

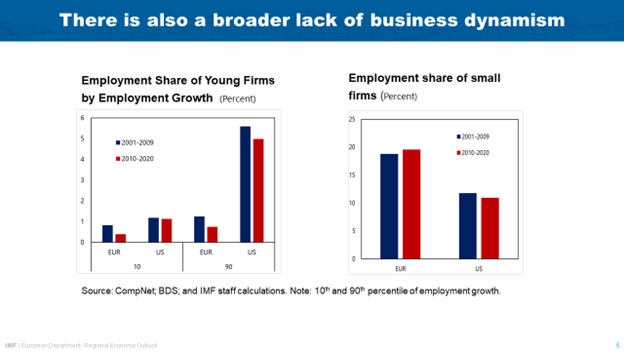

Europe’s promising young firms (those which are 5 years old or younger) tend to have a smaller footprint in the economy compared to the U.S.

U.S. top-performing young firms—these in the highest decile of the employment growth distribution—make up around six times the share of total employment of their European counterparts.

Moreover, some European countries show low exit rates of unsuccessful firms.

Combined, these facts explain why Europe has an overabundance of small mature firms. European micro-firms account for 20 percent of total employment—twice as much as in the U.S.

Removing Intra-EU Barriers Can Lift Productivity

What explains the subdued productivity growth among Europe’s large leading firms? We find that two key factors matter: market size and the financing structure.

Let me start with market size.

The U.S. and Europe’s economies are comparable in terms of the economic size and in terms of population, each representing about 15 percent of the global economy. Yet, Europe’s market is much more fragmented: trade intensity between EU countries—that is, cross-border trade between member countries in ratio to the EU’s GDP—is less than half the trade intensity between U.S. states.

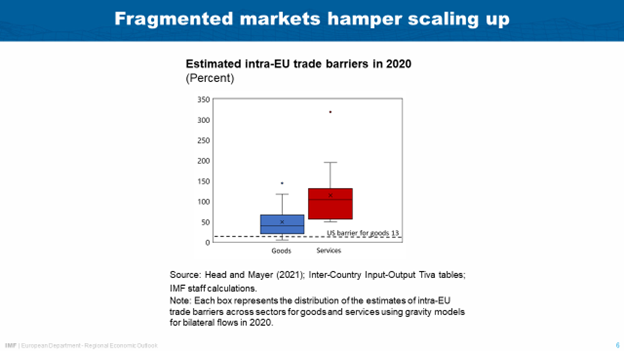

This gap reflects the large trade barriers still in place between EU countries. We estimate that the average cost of selling goods across EU member states is equivalent to a tariff of around 45 percent, while across U.S. states this tariff equivalent is about 15 percent. That is, the estimated costs of trading goods across U.S. states’ borders are about one-third of the cost of trading between EU member states. Even larger barriers exist for services, with an estimated tariff equivalent of about 110 percent on average.

Faced with these barriers, European firms have a hard time exploiting economies of scale and network effects as much as U.S. firms do. This is particularly detrimental in high-tech sectors leveraging digital technology, where competition often takes the form of a “winner-takes-all”.

According to our calculations, deeper market integration would be a gamechanger for productivity—the direct impact of lowering intra-EU trade barriers to the level observed between U.S. states could increase the level of productivity by almost 7 percent in the long term. Gains could be larger should the reduction in barriers also unlock efficiency gains through reallocation toward the most productive sectors in each country.

Availability of Long-Term Risk Capital Can Encourage R&D Investment

The second factor holding back productivity is the fact that the financing model of Europe’s leading firms is simply not supportive of innovation.

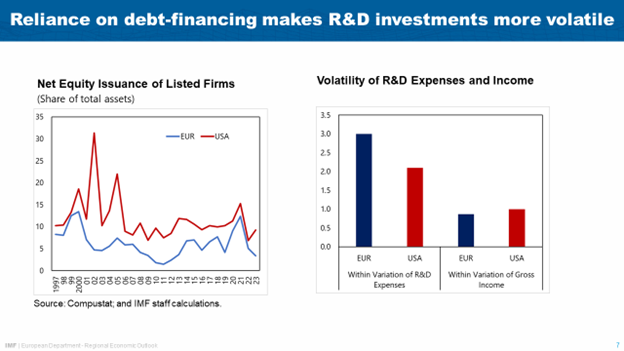

For a given firm size, U.S.-listed firms rely twice as much on equity financing as EU listed firms.

Higher reliance on equity financing is particularly helpful to fund the intangible investments which underpin innovation and productivity gains in the tech sector and, increasingly, in non-tech as well. Limited access to equity markets for European firms makes their R&D investments more vulnerable to shocks. This hurts particularly those types of innovations that require steady funding over lengthy time periods.

Supporting Promising Young Firms Also Requires Human Capital and Easing Financing Constraints

But innovations that push the productivity frontier come not just from large and established firms. They also come from disruptive new entrants that challenge incumbents and may themselves become the future leading firms. Their disruptive innovation also typically pushes current leaders to innovate more.

So, we need more of these promising young firms.

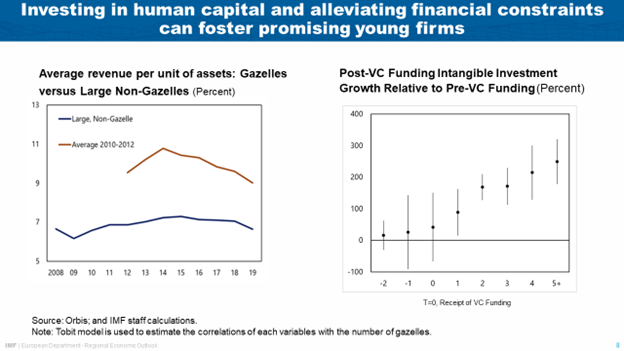

How? Our analysis finds that an important role for investing in human capital exists. At the regional level within Europe, the quality of the labor force is highly correlated with the births of high-growth young firms.

Conditional on these promising young firms being established, we find that easing their financing constraints is critical for them then to grow. This means improving access to funding and lowering borrowing costs—especially for firms which invest more into intangible capital such as R&D— is key. For the most part, that means giving young innovative firms more venture capital investments. In the past decade, VC investments in the EU represented only about one-fourth of what it represents for the U.S. economy. A more vibrant venture capital landscape can make a very big difference to promising European startups: our study finds that venture capital injections lead recipient European firms to double their intangible investments within a year.

The Answers to These Problems Are in Europe’s Own Hands

Let me wrap up by summing up what we see as key reform priorities to strengthen growth and close Europe’s productivity and income gap with the U.S.

In the short term, European policymakers need to do their part in reducing elevated uncertainty. In advanced Europe, this means a smooth loosening path for monetary policy and implementation of the new fiscal rules to ensure buffers are in place when future shocks hit.

When it comes to durably lifting potential growth, Europe has the power to shape its own future. But this will require decisive action.

A deeper single market will be key to unleash growth for Europe’s most productive firms. There is scope for expanding firms’ market access within Europe by addressing underinvestment in border infrastructure, opening up protected sectors, pursuing further services trade liberalization, and harmonizing regulations. Efforts to lower trade barriers should be accompanied by advancements towards the EU capital markets union. Many of the required reforms would better harness Europe’s considerable savings and increase the availability of equity financing for firms of all sizes. Easing barriers to labor mobility, for example through greater pension portability, could promote innovation clusters that require talent agglomeration. Indeed—research shows that workers’ costs of migrating between EU countries is about eight times higher than for migration between U.S. states.

But improving business dynamism also requires strong domestic efforts that match EU-level ambitions. Easing remaining administrative barriers to entry would help more people start businesses, especially in services sectors. Tax and regulatory incentives for small firms should be made temporary to incentivize firm growth. Finally, supporting tertiary education and addressing skills’ mismatches are critical to foster ideas creation through new firms and technology adoption by existing businesses.

The EU must find common ground for removing barriers to goods, services, capital, and labor flows within the single market. These efforts will need to span multiple areas, opening protected sectors, lowering regulatory costs of operating across borders, expanding the capital markets for innovative ventures, and investing in education. This is no small endeavor, even more so at times of rising fragmentation and limited political appetite for reform. But a thriving business sector grounded in a more integrated market can help close Europe’s large productivity and income per capita gaps while also delivering more economic resilience.

And that second part is important: it is not only about increasing per capita GDP through enhancing productivity, but this is also key in strengthening economic resilience which is so essential in this shock-prone world. For us, the advice is: it is critical to tackle this agenda now. It is a big one, but it can be done.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org