Central Banks and Central Banking in a Highly Complex World: Demonstrating Commitment and Preserving Credibility

October 1, 2024

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Good morning and thank you very much for the invitation and the warm welcome.

Today, we gather for this conference, at a crossroads in our effort to restore price stability.

In many countries, headline inflation is back to more comfortable levels. Moreover, the extreme uncertainty surrounding our economic models has receded. This means that monetary policy can again be guided more by forecasts, and it can look through short-term variations in current data.

However, in other countries, the outlook is less certain. There, high headline inflation and sticky core inflation are reminders that our mission is not accomplished yet.

Efforts to reduce inflation over the past two years have reasserted a crucial tenet of central banking: Stay true to your mandate. Yet, this should not prevent us from asking if—and how—monetary policy strategies need to adapt in the future.

In addressing this question, I will focus on three key themes.

First, I will revisit how central bank frameworks have contributed to economic stability, particularly in the CESEE region.

Next, I will discuss how recent events, in particular Russia’s war in Ukraine, have tested the resilience of central banks’ frameworks and the calls on central banks to expand their mandates to address wider societal challenges.

And finally, I will provide a few thoughts on what lessons we can take forward.

Let me start with central bank frameworks.

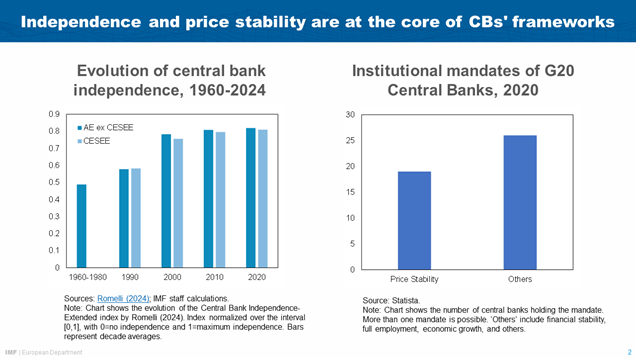

We are used to seeing central banks primarily as guardians of price stability. This is certainly at the core of their business. But many central banks have had—and some still have today—a much broader range of responsibilities that goes well beyond price stability.

In Europe, for example, Banca d’Italia acted as buyer of last resort on the primary market of Italian government bonds from the 1970s until its ‘divorce’ from the Treasury in 1981.

Similarly, after World War II, Banque de France was granted extensive powers to influence the allocation of credit to the economy and fulfill a range of economic policy objectives.

This was not an isolated case. Credit-control policies were widespread in the post-war era in Western Europe, to steer credit towards specific industries, accelerate industrialization and foster higher growth.

But central banks have evolved over time in response to changing conditions.

Following the oil price shocks of the 1970s, quasi-fiscal functions and credit policies were gradually abandoned in most countries. The broad scope of central banks’ mandates stood in the way of securing price stability, which became the primary focus from then onward. Mandates were narrowed and central banks were granted institutional independence from political influence. This prevented fiscal dominance and the inflationary bias that goes with it.

The concept of inflation targeting emerged in the 1990s, crystallizing the evolution of modern central banking. The new paradigm for conducting monetary policy built on strong central bank independence from political interference and combined it with a clear price stability mandate.

Inflation targeting also required central bankers to be transparent about how monetary policy decisions were reached and held them accountable for achieving their goals.

Central bank independence may be the foundation of modern central banking. But transparency and accountability are what balances central bank independence with the principles of democracy.

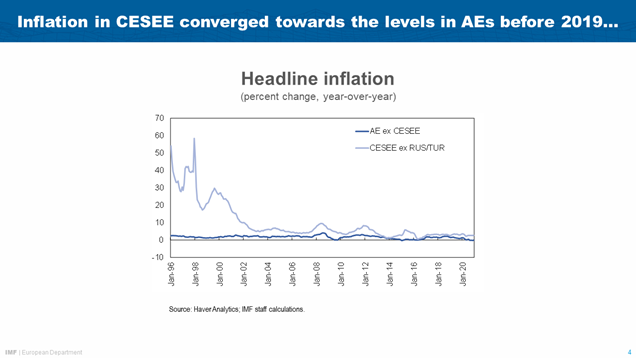

Inflation targeting was adopted by several countries in the CESEE region, though pegs and unilateral euroization are also common. Inflation targeting helped stabilize inflation, which in many cases converged towards the levels observed in advanced economies. Inflation volatility dropped sharply. These successes set the stage for the rapid catch-up of CESEE economies in subsequent years.

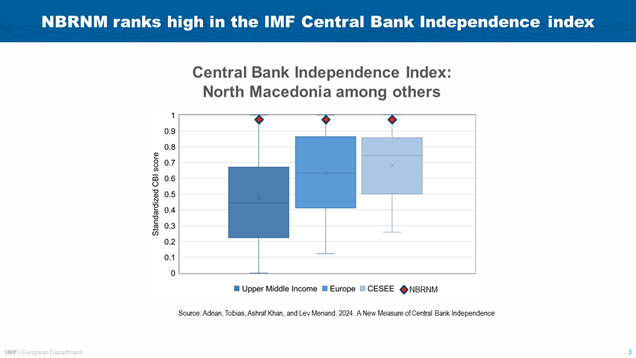

North Macedonia is an impressive example. The creation of an independent central bank in 1992 was crucial to bring down the hyperinflation of the early 1990s. The National Bank ranks very high in the IMF’s new Central Bank Independence Index.[1]

Across the world, inflation targeting frameworks were the basis for a period of unprecedented economic stability and growth known as the ‘Great Moderation’.

Surely, other factors contributed to this outcome. One was globalization. And, for several CESEE countries, structural reforms tied to EU accession played an important role. But the ability of central banks to operate independently from government intervention in the pursuit of price stability is generally viewed as a key pillar of the Great Moderation. It paid dividends in terms of economic stability, growth, and prosperity.

Yet, independence has recently come under increasing pressure. We have seen more calls for premature interest rate cuts and more political interference in central bank decision-making and personnel appointments. These pressures risk jeopardizing the successes achieved and must be resisted.

Let me now turn to my second theme, how recent developments, in particular Russia’s war in Ukraine, are testing the resilience of central bank frameworks.

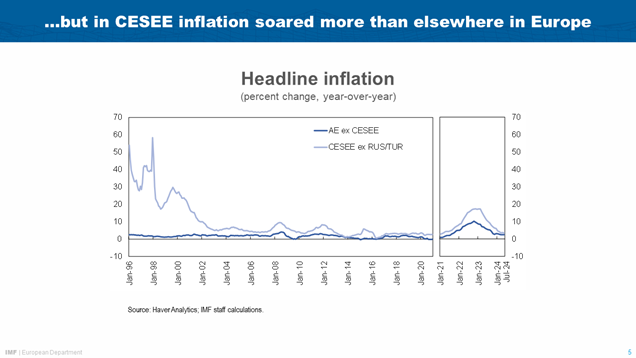

First inflation. The war in Ukraine has been a major supply shock. The sharp increase in inflation hit businesses and households. Effects in CESEE have been larger than elsewhere. This reflects their higher direct exposure through imports, higher food and energy shares in the region’s consumer basket, and second-round effects on other prices and wages. And while inflation has come down, higher prices and input costs have left CESEE countries with a potential competitiveness problem.

But there is a silver lining. Unlike in the 1970s, inflation expectations have remained largely anchored so far. IMF research shows that this time around, tighter monetary policy lowered inflation successfully by preventing cost shocks from becoming entrenched. This is in line with the historical record: analyzing 100 global inflation episodes, we found that monetary policy action is essential in disciplining inflation and that central bank independence helps achieve this with lower output losses by keeping inflation expectations anchored.[2]

This is also the approach the National Bank of North Macedonia followed. After inflation surged to a peak of 19.8 percent in 2022, the central bank's decisive policy rate hikes and strong credibility helped anchor inflation expectations. By August 2024, inflation was back down to 2.2 percent.

The second economic challenge facing central banks is fragmentation.

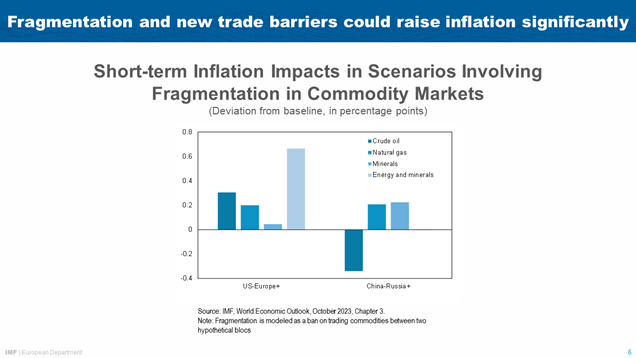

Globalization had slowed well before the war. But the war has contributed to new fault lines shifting the world from a highly efficient, globalized trade model to one marked by regional blocs with increased trade restrictions and higher transaction costs. Indeed, World Bank data show that almost 3,000 trade restrictions were imposed last year. This is five times the amount seen in 2015.

A less integrated global economy is poorer, more prone to shocks, and exposed to higher inflationary pressures. Model-based simulations by IMF staff show that the inflationary impact of trade restrictions imposed on various commodities between geopolitical blocs could be large. For example, a ban on energy and mineral trade between a hypothetical ‘China-Russia+’ bloc and a ‘US-Europe+’ bloc could raise inflation in US-Europe+ bloc by up to 0.6pp in the first year after the ban.[3]

These new economic challenges compound existing ones—Europe’s aging population and stagnant productivity. But fiscal room for maneuver is often limited and needed reforms are always politically difficult.

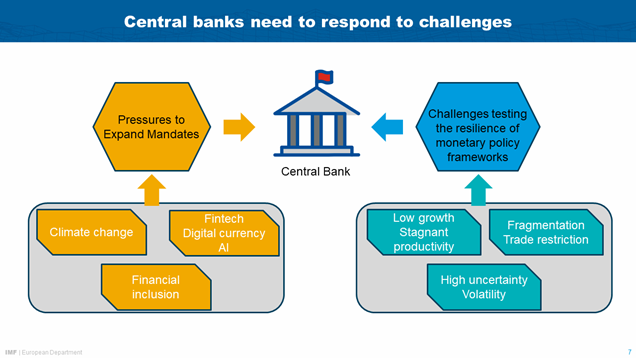

So, it is not surprising that central banks find themselves confronted with calls to expand their mandates to address wider societal challenges.

First climate. This is clearly a macro-critical issue. Central banks are increasingly integrating climate risks into their policy frameworks. Examples include the ECB’s climate stress tests,[4] and the ECB’s and the Bank of England’s decision to prioritize firms with better climate performance in their corporate bond purchase schemes.

Second, digital currencies, fintech, and AI offer significant efficiency gains but also introduce new risks. Central banks must stay ahead of these developments, including exploring the potential of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). The IMF is providing guidance on this front.

A third topic is financial inclusion, including gender-inclusive finance. By fostering accessible and affordable financial services, central banks help reduce gaps, including gender gaps, in financial access.

We will return to some of these topics later today. All of them are important. But let us also keep in mind that broadening central bank mandates can dilute their focus on core monetary policy, invite political interference, and stretch institutional capacity. Given the economic challenges at hand, it will be important to look for possible trade-offs. Central banks main priority is price stability, and central banks will need to manage public expectations accordingly.

Finally, a few thoughts on what lessons can be learned from the extraordinary period we just lived through.

I believe that risk management is key. Fragmentation means that we are looking at a world with potentially lower growth, higher inflation, and higher volatility.

As I emphasized in my 2023 speech at Sintra, during periods of very high inflation and extreme volatility, traditional macroeconomic relationships can break down and monetary policy must adapt and refine the use of its tools to navigate these unprecedented challenges effectively.

This means, for example, central banks will have to be more cautious about “looking through” supply shocks. These shocks can have large second-round effects when inflation is already high. So, a more aggressive policy response is warranted.

As a consequence, strict "forecast-based policy rules", which set the policy rate based only on the medium-term inflation forecast can become ineffective. When inflation is very high, data outturns provide more informative signals about future inflation. The best strategy is to put greater weight on recent data when setting policy rates.

High volatility and uncertainty also call for careful communication and a re-assertion of central banks’ price stability mandate. Clear communication helps anchor expectations. But it needs to be underpinned by action. As discussed, this requires independent central banks. One way to support this is the impartial and merit-based appointment of policymakers to the central banks’ decision-making bodies.

What does the risk management approach mean for countries where central banks have already steered inflation back to close to target and volatility has come down? In these cases, monetary policy can again increase the weight put on economic forecasts and reduce the weight put on current data. This applies to economies with credible policy frameworks and well-anchored inflation expectations, such as the eurozone.

However, a more data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach remains preferable in many CESEE countries where inflation is still further away from targets. Given high inflation persistence and wage growth, the risk remains that upside surprises put upward pressure on inflation expectations. This calls for a continued cautious approach to monetary easing to avoid further tightening and a sharper economic downturn later.

Let me conclude.

Central banks have come a long way. In many countries, including in North Macedonia, they have made significant progress in reducing inflation following the latest surge. This was thanks to improved frameworks, which have enhanced resilience through the recent crises.

However, the "last mile" remains challenging, requiring continued vigilance. Political pressures on central banks have reemerged, threatening to erode the hard-earned credibility that is essential for maintaining economic stability.

The road ahead requires both, continuity and adaptation. Existing frameworks need to adapt to navigate new challenges. Yet it is also critical to uphold the core mandates of central banking, balanced by adequate accountability. Central bank independence should always remain the foundation of the framework. It is a vital public good, that must be preserved and strengthened.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] Tobias Adrian, Ashraf Khan, and Lev Menand, (2024), A New Measure of Central Bank Independence (imf.org)

[2] Anil Ari, Carlos Mulas-Granados, Victor Mylonas, Lev Ratnovski and Wei Zhao, (2023), One Hundred Inflation Shocks: Seven Stylized Facts (imf.org).

[3] See chapter 3 in International Monetary Fund (2023). World Economic Outlook: Navigating Global Divergences. October 2023. The two hypothetical geopolitical blocs are identified based on the March 2022 UN vote on the war in Ukraine. Countries which abstained in the vote, are assigned to the China-Russia+ bloc.

[4] European Central Bank (2022), 2022 climate risk stress test (europa.eu).

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org