Executing a Soft Landing for a Lasting Recovery

March 15, 2024

As prepared for delivery

Good morning.

Thank you, Dean Muštra, for your opening remarks and Governor Vujčić for the invitation to attend this year’s Regional Governors’ Meeting in Split.

Today’s gathering comes two years after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a subsequent energy-price roller coaster, and the advent of a more fragmented global economy.

Against this backdrop Europe has done well, because governments acted fast and decisively.

Unemployment rates have remained low, inflation has declined sharply, and the EU announced a new accession effort—stemming the tide of fragmentation.

I will focus today on what comes next for Europe and in particular the Central, Eastern and Southeastern European or, in short, CESEE region:

- What can businesses and those of you who are getting ready to join the labor market expect in the short term; and…

- …what economic policies are needed to move CESEE and Europe onto the path of a lasting recovery over the medium term.

Global environment

Let me start with an overview of the global setting for this and next year.

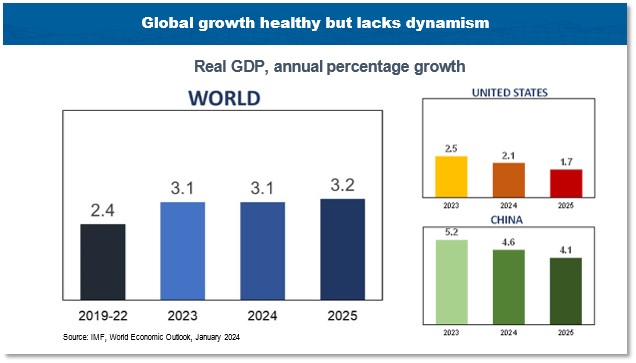

The good news is that the global economy is growing faster compared to the difficult pandemic period, when global output contracted and only slowly recovered thereafter.

But—and here is the bad news—the global economy still lacks dynamism.

At around 3 percent, global growth is well below the historical average of 3.8 percent, which was recorded during 2000 to 2019 and, hence, provides little positive spillovers to Europe.

We expect the US economy to slow as its post-pandemic recovery runs its course.

Similarly, activity in China is cooling as weaknesses in the property sector are expected to persist.

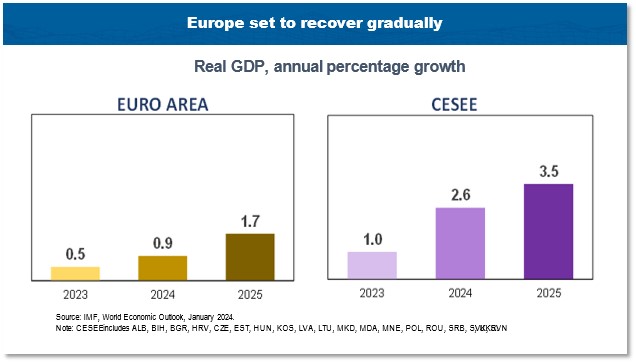

For Europe––after suffering an exceptionally large energy price shock in 2022––we project a gradual recovery.

Compared to dire predictions of a recession at that time, this outcome would be a remarkable accomplishment.

Specifically, we expect growth in the euro area overall to rise from below 1 percent this year to 1.7 percent in 2025.

And in the CESEE region we expect the economies to grow close to 3 percent this year and 3.5 percent next year.

For Croatia which joined the euro area a year ago, growth is robust..

This positive development is the result of strong policies but also helped by a resilient tourism sector.

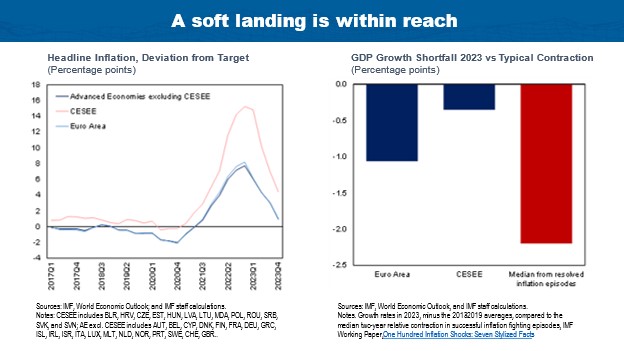

Our forecast constitutes what has been called a “soft landing.”

By this we mean that the decline of inflation in 2024-25 to previous levels is accompanied by only a mild growth slowdown.

This is not a common outcome as I will explain.

As of last month, inflation rates have fallen to approximately one-third of their peaks at end-2022. (Figure LHS).

The fact that the economic costs of the energy price shock and higher interest rates—which have been raised to slow down price increases—have so far been mild is quite remarkable.

As we have documented in a recent study, the drops in economic activity have typically been much larger during previous episodes of disinflation, as the red bar indicates.

But there are some reasons for concern.

Let me start by noting that the prospects of a soft landing are not equally strong across Europe.

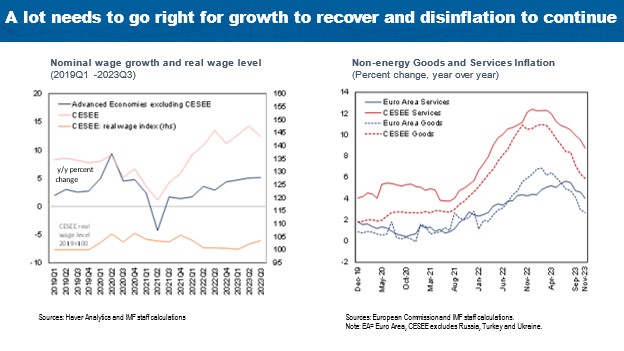

The disinflation process has been uneven.

Core inflation, a measure of underlying price dynamics which excludes volatile food and energy price components, is higher in emerging European economies than in advanced European economies.

In both country groupings, core inflation is coming down only slowly.

And even within CESEE, we are seeing differences.

For example, the decline of the inflation rate is progressing more slowly in Romania, Moldova, Montenegro, Hungary, and Serbia than elsewhere in the CESEE region.[1]

But the more general point here is that the forecast for a soft landing rests on strong assumptions.

One important factor especially in emerging European economies is that labor markets need to cool at just the right pace.

- Labor markets cannot remain too strong as they may keep wage growth above long-term productivity growth and steady state inflation rates–thereby leading to protracted inflation and a loss of competitiveness.

- But labor markets should also not cool so much that labor income would no longer be able to support robust private consumption.

Where are we in this respect?

As of end 2023, wages in the CESEE region were growing at above 10 percent year over year.

On the one hand, robust wage growth will help restore some of the purchasing power that households lost due to inflation.

By the end of last year, average household wages in real terms recovered enough to bring real wages back to at least their 2019 levels.

On the other hand, if wages are growing too fast, this might backfire and re-ignite inflation.

Our analysis shows that wage growth in the CESEE region at around 4-6 percent this year would balance the need to restore purchasing power and return inflation back to target levels.

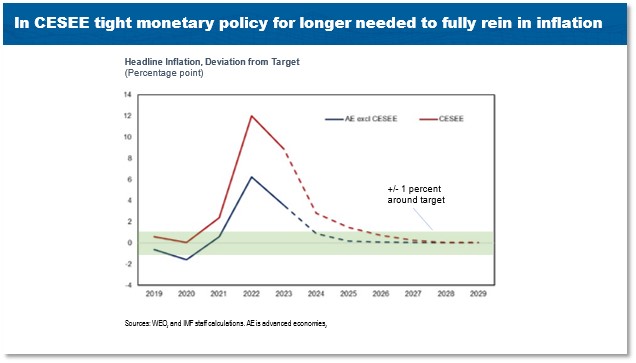

Overall, given current levels of inflation and price and wage dynamics, our forecast suggests that achieving price stability targets will take one year longer in the CESEE region compared to advanced European economies.

In general, the underlying inflationary pressures in the region remain stronger than in advanced economies. Many central banks in the region should therefore maintain a tight monetary stance for longer than for example the ECB.

This does not necessarily mean that policy rates cannot fall. In countries where inflation expectations are dropping fast, nominal rates can be lowered without necessarily changing real rates and the policy stance.

The cost of erring on the side of too-loose monetary policy is significant when inflation is persistent. So, central banks should weigh negative news on inflation more when considering their next policy steps compared to positive news.

This bias is to avoid that upside inflation surprises materialize which could feed into expectations of sustained high inflation—a costly outcome for businesses, households and the economy as a whole.

Bringing inflation towards target also needs the support of fiscal policy.

The planned fiscal consolidations in 2024 and 2025 which roll back extraordinary support extended to households and corporations during the pandemic and the energy crisis are appropriate and will help fight inflation by containing demand.

Achieving a soft landing will not be easy, but it is critical, also because it will help policymakers getting ready for what will be an even more difficult task ahead: raising CESEE’s growth prospects in a durable manner.

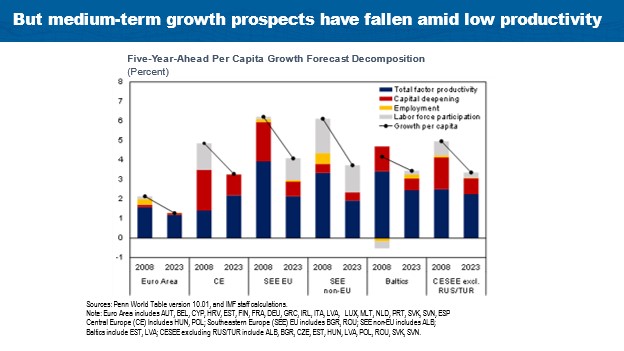

Already prior to COVID, the speed of convergence of emerging European economies’ towards advanced European economies’ output-per-capita levels has slowed.

To put the lack of dynamism in perspective:

- The growth slowdown in the CESEE region between the early and late 2010s implies that—at that reduced growth rate—CESEE countries would converge to average living standards in the EU (excluding CESEE member) by half a century later, by around 2100.

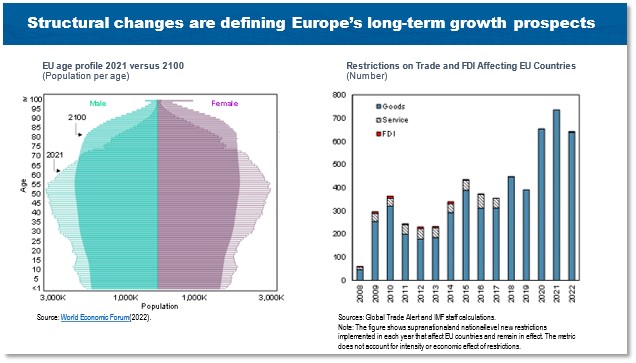

Four structural developments affecting convergence need attention. They are:

- Demographic changes. Population aging is already reducing the labor force. In the CESEE region, pension and health care spending needs are estimated to grow by 5 percentage points of GDP by 2050.

- High energy costs. Addressing this issue is intertwined with tackling the next challenge:

- Climate change. Adaptation requires investment in infrastructure and clean technologies; the Next Generation EU (NGEU) funds are an important and substantial funding source. Implementation and uptake have been slow in the CESEE region and require attention.

- Geoeconomic fragmentation is raising the costs of international trade and limits access to critical commodities. Trade restrictions have already increased sharply, by three-fold in 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic period (chart rhs) raising trade costs and dampening export earnings.

Addressing these challenges requires economic resources, and, to generate them, countries need to grow at a healthy clip.

Here, the CESEE region has its work cut out.

Growth prospects in advanced and emerging European economies have dimmed.

The latest 5-year forecast for Europe’s per-capita growth from last October (2023) is substantially below forecasts made just before the global financial crisis some 15 years ago.

These slower growth prospects are pervasive and apply to all parts of Europe: the euro area, central Europe, south-eastern Europe, the Baltics, and the CESEE region.

But Europe’s growth prospects have not only slowed relative to its own past, Europe has also fallen further behind other advanced economies.

When compared to the US, output per capita is in Europe about 30 percent lower on average after correcting for price and exchange rate changes that do not reflect changes in living standards.

The difference is even bigger for countries in the CESEE region at 45 percent

A decomposition of the gap in per-capita income into contributions from labor, capital, and productivity shows that that the main reason for Europe’s lower per capita GDP—accounting for about two-thirds—is substantially lower productivity.

Thus, the main goal for European policymakers should be to create conditions for faster productivity growth.

Here investment comes into play.

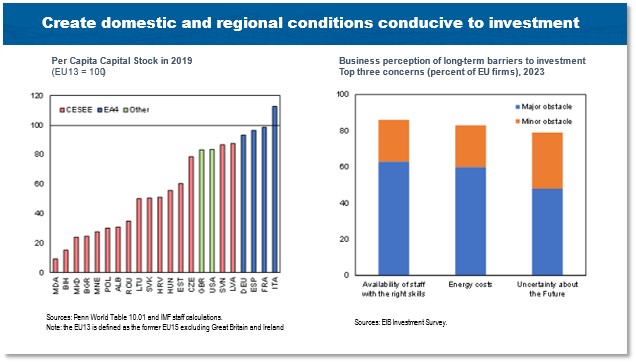

The level of productivity in a country is closely linked to the size of its capital stock.

And new machinery and upgrades in IT equipment and software are some examples how new technologies—embodied in capital goods—enter economic processes and increase productivity.

In the CESEE region, the per-capita level of capital is substantially below levels observed elsewhere in Europe (chart LHS).

What can policymakers do to facilitate more investment?

A recent survey of businesses by the European Investment Bank (RHS) identified several barriers to investment. Specifically:

- First, firms are concerned about the availability of skilled labor. Continued support of education and universities remains key. But countries also need to improve active labor market policies—such as reskilling and vocational training for job searchers—to help fill skill gaps. At the EU level, common professional certifications would facilitate labor mobility.

- Second, despite the fact that prices have come down considerably, firms remain concerned about high energy costs. Reforms of energy networks regulations but also investments are needed to improve the efficiency of energy production and distribution together with a shift to more renewable energy.

- Finally, businesses are concerned about uncertainty about the future.

Policymakers can respond to this uncertainty through credible institutions and responsible policymaking. By delivering sound macro-fundamentals–– low inflation, sustainable public debt— through trustworthy institutions, policymakers can reduce uncertainty about the economic conditions for businesses and households alike.

Credible policies and strong governance are the bedrock for a strong economy.

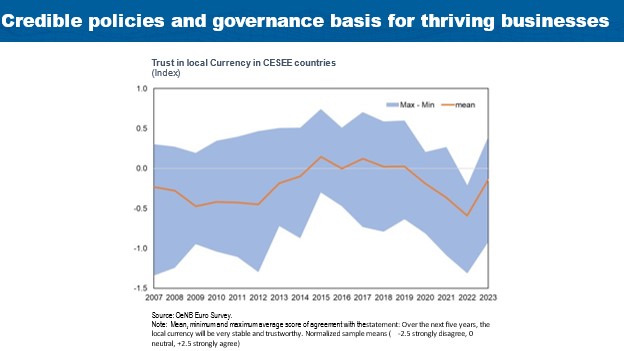

Several studies have shown that trust in economic institutions plays a critical role in reassuring savers and investors alike of the stability of their economic well being.

During 2021-2023, we could see an erosion of trust in the CESEE region.

A large-scale survey of CESEE countries by the Austrian National Bank shows that the belief in the stability and trustworthiness of local currencies was shaken post-COVID (chart).

Here we have a word of warning.

Several central banks in the region have been under strain from political interference.

Let me be clear, central banks need to be able to fulfill their mandates on inflation.

For this, independence is essential. Interference erodes trust and makes policymaking more costly.

Weak institutions also open the door to poor governance and corruption.

There is resounding evidence that robust governance via resilient anti-corruption frameworks is a precondition for attracting investment into a country.[2]

The good news is that in 2023 trust indicators have improved across all surveyed countries.

By assuring a soft landing, central banks and government can regain this hard-earned trust which is an indispensable underpinning of a healthy business environment.

Another area that deserves the attention of policymakers is the promise of growth from technological progress.

The advances of artificial intelligence are captivating the world. Its applications could jumpstart productivity, boost global growth, and raise incomes around the world.

Yet, AI could also replace jobs and deepen inequality.

It will take some time before we know the impact.

And at this stage, it is difficult to foresee the economic effects, as AI will ripple through economies in complex ways.

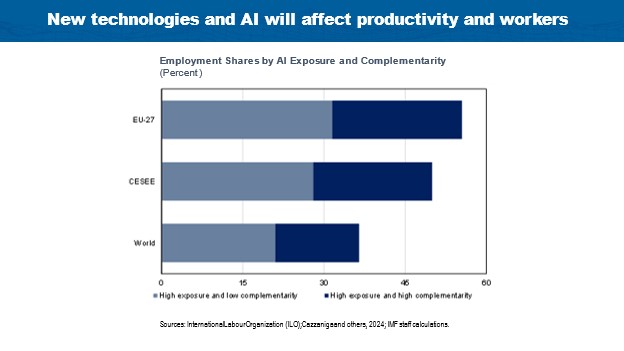

Nonetheless we can and should start assessing which types of occupations AI will likely affect; which activities it will complement, and which ones it may replace.

Recent work by the IMF shows that close to 60 percent of all workers in the EU will likely be affected by AI in one way or another (chart). For the CESEE region, the share is close to 50 percent.

Among those affected, for about half of them AI will complement their work and raise their productivity. For the other half, AI will be less complementary and replace some tasks or activities.

In most scenarios, AI will likely worsen overall inequality.

It will be more advantageous to the higher-skilled and reduce the need for medium and low-skilled workers alike. This is a troubling prospect that policymakers should assess and respond to as needed.

The availability of social safety nets and retraining programs mentioned earlier are of even more importance from this perspective. They will help make the AI transition more inclusive and curb inequality.

To conclude.

If there is one key message to leave with you, it is that policies matter.

With the right policy mix, the CESEE economies can secure low inflation and increase the long-term growth trajectory.

At the macroeconomic level this means monetary policy should maintain a tightening bias and carefully assess the timing and speed of easing.

Planned fiscal consolidation is appropriate and should help with disinflation.

Achieving a soft landing is critical to prepare countries for an urgent but critical task, raising CESEE’s growth prospects in a durable manner.

Crosswinds from an aging population, uncertainty about energy costs, and geoeconomic fragmentation call for forceful growth-enhancing reforms.

A prime task is getting the business climate right to help boost investment and productivity.

New investments––and their embodied technology––will also support the energy and green transition.

Here, by strengthening governance and anti-corruption frameworks countries can durably improve conditions to attract investment domestically and from abroad.

Governments need to also facilitate the transition to a more efficient economy by ensuring that education systems equip students with the skills to harness new technologies including AI.

But they also need to develop re-training and upskilling programs as technological progress and AI will affect work more broadly.

Success in the region will require forward looking reforms now that will pay off later.

This is an investment worth making—and one that we at the IMF stand ready to support.

Thank you.

[1] CESEE countries which have either had the smallest decline in core inflation by January 2024 relative to the post-2022 peak core inflation rate or had core inflation rates at or above 8 percent y-y by January 2023.

[2] How Reform Can Aid Growth and Green Transition in Developing Economies. New approaches to governance, business regulation, and trade can boost output by 4 percent in two years and help countries curb emissions Christian Ebeke, Florence Jaumotte September 25, 2023