The Panama Canal with the Centennial Bridge in the background. The pandemic has taken a toll on trade in Central America. (photo: Lokibaho by Getty Images)

When it Rains it Pours: Pandemic and Natural Disasters Challenge Central America’s Economies

December 17, 2020

COVID-19 has not spared Central America. Confirmed cases have multiplied to well over 600,000 in November, with the death toll exceeding 14,000.

Related Links

Countries have taken prompt containment measures, with the strictest enforced in the Northern Triangle of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, amid inadequate testing and tracing capacities and limited access to basic health services. Insufficient hospital capacity and protective equipment, elevated poverty, and, in some cases, densely populated cities have worsened the human toll. Low levels of testing and weak reporting in some countries suggest the situation might be even worse than official statistics.

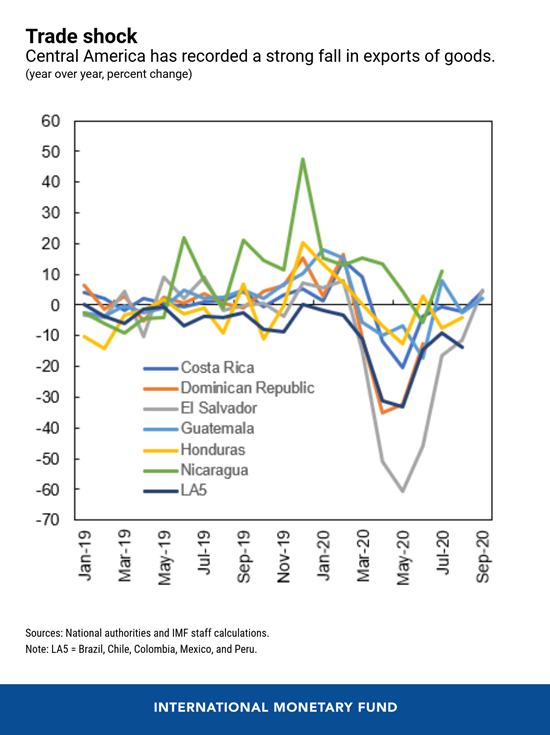

The economic toll has been heavy as well. The trade shock has been particularly strong in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama (via a severe drop in revenues from lower traffic in the Canal).

On average, lockdowns have contributed about 70 percent to the slowdown, especially in Panama, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic, reflecting the combination of stringent containment measures and a higher share of contact-intensive sectors.

Hurricane season

Multiple natural disasters added to the economic destruction and increased the risk of worsening the pandemic: two tropical storms in June in El Salvador; a severe drought in Honduras; and two recent back-to-back category 4 hurricanes that hit Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Honduras particularly hard.

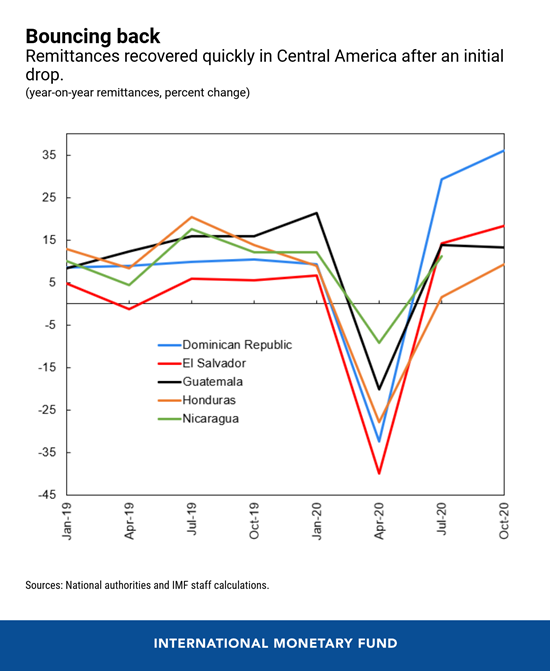

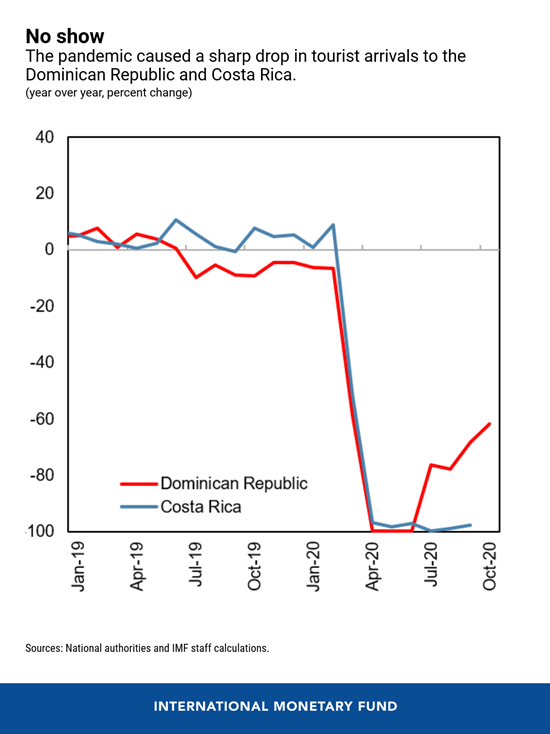

Several factors have helped mitigate the double health and climate shocks, in particular a solid agricultural performance and, since May, a strong rebound of remittances, on which most Central American countries depend heavily. Lower oil prices benefitted the region, a net importer. Medical equipment exports have partly offset the tourism downfall in Costa Rica.

Nonetheless, with tourism and trade unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels soon, real GDP is projected to contract sharply in 2020, by nearly 6 percent, ranging from -2 percent in Guatemala to -9 percent in El Salvador and Panama. The speed of the recovery will depend on countries’ exposure to the world economy; the stringency of containment measures as infections continue to rise; the availability of vaccines; and their ability to sustain supportive policies. The economic impact of the recent natural disasters, still being assessed, might further lower these estimates.

More with less

Extensive fiscal and monetary support have helped mitigate the economic and social impact. Most countries increased spending, extending subsidies and transfers to reach the informal sector that accounts for up to 60 percent of employment in some countries (for instance, in Guatemala and Honduras). Countries granted temporary tax relief to key economic sectors, and provided liquidity support and credit relief through rate cuts, lending facilities, credit guarantees, and regulatory forbearance.

The fiscal cost of these measures has been significant, squeezing countries’ already strained finances and causing public debt to swell. But targeted support will need to continue, to resolve the health emergency, support the nascent recovery, and prevent that already elevated levels of poverty, inequality, and unemployment rise even more.

Emergency financial assistance from the IMF and other multilateral institutions has provided temporary relief, and most countries issued debt in international markets. But financing needs remain large, averaging 9 percent of GDP over the next three years, amid tight financing conditions. A few countries have already approached the IMF for additional support, which could catalyze financing and anchor their adjustment programs

The road ahead

Looking ahead, fiscal consolidation will be necessary to rebuild countries’ financial health, and a broad political and social dialogue will be critical to build support for gradual, transparent, and sustainable medium-term plans. Spending should be reprioritized toward adequate, well-targeted social safety nets to protect the vulnerable, and efficient public investment in health, education, infrastructure, and technology to narrow the existing skills and infrastructure gaps and enhance resilience to future shocks.

Ambitious structural reforms will need to complement macro-policy actions to boost competitiveness and increase growth potential, reduce inequality and informality, support a strong and green recovery, and build resilience to climate shocks. Regional authorities are already moving in this direction, preparing a reconstruction plan that prioritizes financing to projects that adapt and respond to climate change effects.

The financial system will require attention, as widespread job losses and business closures will likely weigh on banks’ health. Supervisory authorities will need to support flexible use of capital and liquidity buffers consistent with international standards, while closely monitoring financial stability risks and preparing to unwind the support measures when warranted.

As it recovers from the health emergency, the region will face multiple challenges on the way to an inclusive and sustainable economic recovery. It will require careful phasing out of emergency policies to reduce debt sustainability risks, while protecting the nascent recovery and the social fabric. Access to additional multilateral loans and market financing will be needed to meet sizable medium-term financing needs.

This article draws on joint work by the IMF’s country teams working on Central America, Panama, and the Dominican Republic.