Transcript of a Press Conference on the IMF's 2000 Annual Report

September 14, 2000

Thursday, September 14, 2000

Washington, D.C.

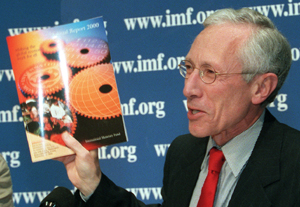

Mr. Stanley Fischer |

Before introducing today's speakers, let me first remind you of the other briefings that are coming up ahead of the Annual Meetings in Prague. Next Tuesday, September the 19th, at 10 o'clock, the IMF's Economic Counsellor Michael Mussa will lead a briefing on the latest World Economic Outlook. The following day, on September the 20th, at the same time, the Managing Director Horst Köhler will give his pre-Annual Meetings press conference. Please note that, of course, both these events will take place in Prague.

Let me now introduce today's speakers. To my immediate right is Stanley Fischer, the First Deputy Managing Director of the Fund. To his right is Eduard Brau, the IMF Treasurer, to whom Mr. Fischer may turn for questions that relate to the financial statements that are in the Annual Report. And to Mr. Brau's right is David Cheney, the chief of EXR's Editorial Division, which produces the Annual Report.

The subject of this briefing is the 2000 Annual Report. I believe that Mr. Fischer has some opening remarks, and then we'll take questions.

MR. FISCHER: Thank you very much, Graham, and congratulations to you and the team for producing this new enhanced, warm, fuzzy, "Making the Global Economy Work for All" report on the Fund. It's certainly one of the best-looking we've ever had, and it's actually got a lot of good news in it as well.

Let me summarize a few highlights and then let's take questions.

First of all, this is substantially out of date. It relates to the year that ended April 30, 2000, and the tradition is to have it ready for the Annual Meetings. So you may know a lot of what's already in there.

The second general fact about it is that it's a report of the Executive Board, and they are responsible for the text. They've gone through it line by line and cleared the whole thing.

Now, what were the highlights of Fiscal Year 2000, which ends in April? And I'm unfortunately going to talk in this special IMF currency, which is the Special Drawing Rights, or SDR. Currently—Ed will correct me—about $1.27 or something.

MR. BRAU: Twenty-nine.

MR. FISCHER: Twenty-nine. When this was completed in April for the year in which this ended, April 2000, it was about $1.32. So if you hear SDR, multiply by one and a third and you'll get it in dollars.

Last year our lending dropped very sharply as a result of the calmer conditions in emerging markets and the rapid improvements in several of the crisis countries. We loaned 6.3b SDRs last year—that is, in our regular loans, not our concessional loans—and that is less than one-third of what we had done in the previous fiscal year. And repayments—now, we lent 6.3 billion, but repayments doubled to 23b SDRs. So we took in a lot more than we paid out. And in the past four months, just to bring it up to date, we've lent another 1.2 billion, but we've taken in 4.8b SDRs. So we're rebuilding our reserves very rapidly. Of the 4.8b that we've taken in in the last four months, almost half came in the form of an early repayment from Mexico.

In terms of our low-interest concessional loans to poorest members under the PRGF, the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility, we lent half ab SDRs last year, which is down from 0.8b in the previous fiscal year; and since April, lending and repayments have been about the same at 200 million SDRs.

Now, the net effect of all this was to reduce the amount of IMF credit outstanding, the total amount of our loans, to 50.4b SDRs at the end of fiscal year 2000, down by 17b SDRs from that at the end of fiscal year 1999. And our critical liquidity ratio, the concept of which is easy to understand, the precise definition of which I don't want to waste your time with. It's a measure of how much liquidity we have. It was at its lowest point ever in October 1998 at under 30%. That was before we got the quota increase. Following the quota increase, but especially following all the repayments we've been getting, our liquidity ratio at the end of last month is higher than it's ever been at 178%. That is a measure of how much we have relative to the amount that could be called on from the IMF at very short notice. And what can be called on is countries have a right to access a certain part of their quotas in the Fund, and in addition, when we've committed to a loan, we regard that as something that could be drawn on.

So the financial position of the IMF is much stronger than it was two years ago, even stronger than it was a year ago, and even than it was four months ago. And that is very important good news.

It is also an indication that the concept that the IMF should be a crisis lender in aggregate is fundamentally the way we've been behaving. When there's trouble we lend a lot. As the crisis ends, the money comes in and it's come in pretty fast, in part because of prepayments, in part because the new facilities we have, particularly the SRF, the Supplemental Reserve Facility, encourage early payment by having a rising schedule of interest rates for repayment.

So that's point one. That's what a large part of this is about.

The second theme in the report is the efforts to strengthen the international financial architecture. There was a lot aimed at better crisis prevention and management, and much of it relates to the transparency of the global economy and of the IMF itself.

First, surveillance. We've strengthened our scrutiny of economic and financial policies in member countries and in international capital markets. Our focus is supposed to be on matters that affect macroeconomic stability. That means exchange rates, macroeconomic policies, the financial sector, the capital account, and the international capital markets. That's what we're going to focus on, and as those of you who have been following Mr. Köhler's—the new Managing Director's—emphases in recent days, he is laying very, very heavy stress on the financial sector, international capital flows, the need to make those a focus of IMF concern, and to build up our expertise in those areas.

You, particularly the journalists here, are aware of the fact that we're releasing, or our members are agreeing to release far more of the products of IMF surveillance. We now have 80% of members agreeing to release PINs, the Public Information Notices, which summarize Board discussions. And I think even more impressively, 60 countries agreed to publish the actual Article IV reports, and that is a huge change, one of the things which I think will help inform the markets, help give citizens in countries an outside view of what their policymakers are doing, and not the least factor, by getting the IMF to publish its analysis, bring outside professional criticism of what the IMF is doing that will help us raise our own standards.

Third, we've made progress in implementing and monitoring observance of international standards and codes of good practice and various policies. That includes data dissemination, transparency of fiscal, monetary, and financial policies and banking supervision. Those are areas in which the IMF itself produced some of the standards and is doing much of the monitoring. But there is a broader international effort where various agencies are producing codes and standards in their own areas of expertise. And work is afoot to bring all these standards together, and then the assessments of all these standards together in ROSCs, reports on the observance of standards and codes.

Fourth, something which I believe is very, very important in the Fund's work, the Financial Sector Assessment Program, which we do jointly with the World Bank. Those are missions sent to member countries to provide a comprehensive assessment of the financial system. We go with IMF and Bank people, and we typically get experts from central banks and supervisory agencies of other countries. And this means that the supervisors of the financial system in any country can have access to an objective, outside, highly experienced group able to tell them what's going on, as seen by experts from elsewhere.

This has happened in many developing countries—Canada has also asked for such an assessment—to indicate that it is important not only that developing countries and emerging market countries strengthen their financial systems, but also that the industrialized countries do so. We did a pilot project of 12 countries. It's going to be upgraded, increased to 24 countries in the coming fiscal year.

Fifth, we've been working to assess vulnerabilities and risks that confront countries. We do that in part by improving the quality of data but, more importantly, we're also using a variety of vulnerability indicators that have been developed inside and outside the IMF to provide summary indicators of the vulnerability of countries to external shocks. You have to keep updating these things. It's almost law that if you identify an indicator, its value will decline over time because the authorities will pay attention to that, and you have to keep anticipating which is the next one.

Number six is private sector involvement. There has been a lot of progress in understanding how to secure private sector involvement in preventing and resolving financial crises. The Annual Report covers work done through the end of April 2000, which takes us through the Spring Meetings of the IMF and the Bank. We have continued since then, and differences in views that were quite apparent between shareholders among the industrialized countries—with a desire by some for a very formal framework and by others for a case-by-case basis—are being narrowed. And I believe we're working toward a framework that is going to be called, depending which side of the spectrum you came from, either a flexible framework for those who like form, or constrained discretion on the part of those who like discretion. Somewhere in the middle we will be getting a framework that recognizes that one of the troubles with financial crises is that they're never quite like the previous ones. If you prepare a wonderful plan that would have been perfect for the last crisis, it quite likely will be inappropriate for the next one. So you need that element of flexibility.

Number seven, the review of lending facilities. A senior IMF official has just reported that we are making good progress in completing our review of the lending facilities and there's good reason to hope that by Prague that would be completed in a way, importantly, which would make the Contingent Credit Lines much more flexible and usable and, secondly, which would ensure that there are incentives for early repayment relative to the structure of current obligations in the way the IMF does business. That discussion is going on as I speak.

Let's turn to the Fund's work with the poorest members. We've sharpened our focus on poverty reduction, with the introduction of the PRGF replacing the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility, and with principles that you are all familiar with that lay very heavy stress on Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers in the HIPC Initiative-the debt relief initiative, and with the greatest stress for non-HIPC PRGF countries on directed antipoverty measures. We have worked out a good division of labor with the World Bank. We cooperate extremely closely in the design of the overall program. We will take care of the macroeconomics. The PRSPs will have in them the social policies designed to reduce poverty, focused directly on poverty. Of course, we believe that macroeconomic policies also help reduce poverty if they're good. And it will be the responsibility of the Bank and the regional development banks to undertake or to support those structural policies through their lending.

We had by the end of last financial year committed 3.5b SDRs to 31 countries under the PRGF, and that is up now to 3.7 billion.

The HIPC Initiative you know all about. We had committed 762m SDRs to 12 countries by the end of August, and we've disbursed more than 240m of that. We are working very hard to get to the decision point in the HIPC Initiative for about 20 countries by the end of this calendar year. And, third, we are making progress in getting financing for the PRGF and the HIPC Initiative. By the end of April 2000, 60% of the contributions pledged by member countries were either in hand or being paid. Meanwhile, as you know, we've raised part of our share for the financing through the so-called off-market transactions in gold.

What else are we doing? The Independent Evaluation Office, the Board agreed in April to be ready at Prague with a decision on how the Independent Evaluation Office will operate. That decision was made yesterday. The office should be operating by the spring.

And our own transparency has gone up remarkably. We're releasing independent evaluations. Ed Brau, to his credit and to the gratitude of management, has managed to produce a set of accounts that can be understood by mere mortals and which follows international accounting standards. They come out weekly and you actually can figure out what's going on. We provide more details also on the financing of our loans and our transactions with member countries.

Our external website got five million hits last month. This I think is probably much more than it was five years ago when it was probably zero, and our problem now is that we will need, as the volume of information increases, to actually give some more thought to designing the website in a way—all the feedback I get is good. I'd be happy to hear more. But there's so much there that we probably also need more guidance through it.

There are two last measures. Safeguards on the use of IMF resources was a very contentious matter during the year, and we have strengthened the safeguards on the use of our resources in ways that you can see on the Internet and that are described here.

And finally, technical assistance, we are doing more of it. It accounts for 20% of the Fund's costs. It's a very large activity which doesn't get much publicity, and we're also expanding pretty rapidly our training institutes. We now have joint training institutes and programs in Asia, in Singapore, and we'll be establishing at least one more in Africa, in Cote d'Ivoire, and in the Middle East. We have a few more on the way. This idea of putting out training institutes jointly with member countries in all continents—we also have the Joint Vienna Institute—is one that is highly appreciated and I think highly productive.

Well, let me stop there and take questions.

MR. HACCHE: Thank you, Mr. Fischer.

Preferably, please, at least at first, can I ask for questions on the Annual Report, and ask you in the usual way to identify yourselves by name and affiliation.

QUESTIONER: As you said a couple of years ago, you were worrying that you were running out of cash. Now you seem to be totally flush with it. Do you have too much? Might you be in a position where you can start giving some back and really pleasing the U.S. Congress?

MR. FISCHER: That doesn't make any sense. The quotas, in the discussion of the needed size of the Fund, are based on long-term trends in the global economy, including the fact that the capital markets have become much bigger. We have far, far failed to keep pace with the capital markets. We should fail to keep pace with the growth of the capital markets. But that we needed to grow significantly as a result of developments in international markets was clear. You don't give the umbrella back, or you don't destroy the umbrella, when it stops raining, because there is a chance it's going to rain again.

MR. HACCHE: Next, please?

QUESTIONER: Can you talk about how changes in conditionality happened over the last year and a half and how they're going to change over the next year?

MR. FISCHER: There are three items I should report on. First, in the context of the HIPC Initiative, the combination of work with the World Bank, including the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, has led to a very different focus in that part of the Fund's work. The direct focus on poverty reduction and the fact that we're figuring out better ways of cooperating with the World Bank in that regard is one important development.

The second important development is that there's an increasing emphasis on governance related to the fact that it has become more and more acceptable to talk about the problem of corruption and more and more clear that it is unacceptable to make IMF funding or public sector funding available in countries where, because there's poor governance, you don't know what's going to happen to the money. So there's much more attention on governance in terms of safeguards, assessments, and all that.

The third feature is that the Managing Director is anxious, and I believe correctly anxious, to reduce unnecessary conditionality in IMF programs. The analytic definition or the principle on which we're going to operate is that the IMF should be concerned with macroeconomic policies, exchange rates, fiscal, monetary policies, and the financial sector, and in all those cases with the institutional and structural underpinnings of those sectors. That should be where we focus.

Now, that is a very good general principle. It's an organizing principle. Precisely how it works out we're going to have to work on in the next few months, possibly the next year, by seeking to apply those principles concretely in individual cases. So it's not done yet, but that's the direction that we will be moving in in the months ahead.

MR. HACCHE: Next, please?

QUESTIONER: Mr. Fischer, can you repeat the figures of the IMF's involvement in the HIPC Initiative, the volume and the countries?

MR. FISCHER: I can certainly repeat what I said. I believe, incidentally, we will be handing out a summary of the report, either now or at the end of the discussion.

Under the PRGF itself in terms of flows, we lent half a billion SDRs last year, which is down from 800 million in fiscal year 1999, and since April we've lent another 200 million and have been repaid that much. Then there's the question on what is the outstanding stocks. In the PRGF the outstanding stock of loans or commitments under the PRGF is 3.5 billion, and it's loaned to 31 countries, 3.5 billion at the end of the year, up now to 3.7 billion.

QUESTIONER: I asked on HIPC.

MR. FISCHER: On HIPC itself. Under HIPC, the loans that have been made—I mean, we've so far reached the decision point with 10 countries, and we're aiming—we have reason to hope we can reach the decision point with 20 countries, with an additional 10 by the end of this year.

MR. HACCHE: Next, please?

QUESTIONER: On this Financial Sector Assessment Program, where you have 12 countries, you said you want to expand to 24. Do I take it that the 12 countries now are all developing countries and you want to get industrialized countries? Can you elaborate on that?

MR. FISCHER: No, among the 12 was, in fact, Canada, and there are a couple of emerging market countries. Emerging market are developing countries. And I think there is one other industrialized country. I couldn't swear to that. I'm not certain. But we want to expand in both directions, that is, a few more industrialized countries and a few more developing countries.

It's a sort of trade-off. We need to balance two things, countries' needs and systemic importance. This is a major service to members, so we should make it available to countries that feel they most need it. On the other hand, these resources are quite scarce, so we have to take systemic importance into account as well.

QUESTIONER: I would like to ask a question about quotas. On page 64, the report says that the Board is scheduled to discuss the report and accompanying staff commentary in August 2000. Could you share some thoughts about the discussions as well as some of the progress happening since then, especially related to China and some other Asian countries? Thank you.

MR. FISCHER: The report was discussed, the report of the Quota Formula Review Group, the members of whom are noted on page 64, and thank you for drawing attention to it. It was discussed in August at a seminar of the Board with three of the members of the team being present, and that report and the staff commentary on the report will be published shortly.

MR. HACCHE: Imminently, yes.

MR. FISCHER: Imminently. That's even more shortly.

The authors of the report decided to do it in a way which I think is very interesting. They decided not to do what every country is concerned about, which is to figure out what does the formula mean for each individual country, but to discuss general principles. And they did not do calculations which said where the general principles would lead. They just discussed it from the viewpoint of what the IMF needs, what the quota should look like. And they pointed out that the quota serves many purposes in the Fund, and once you have more than one purpose for something, it's hard to get precisely the criteria that should be satisfied.

The quota is first—and many politicians think of it as-the basis of your share of the vote in the Fund. That's item one. So it's influence in the Board. Second, it determines how much you contribute to the Fund, so how much you have to pay in. And, third, it determines how much you can borrow.

This is, as we sometimes say, like a credit union in that everybody pays in and then members can borrow. So they had to come up with something which included a measure of the need, the borrower side, and of the ability to contribute, the lender side. They basically came up with a two-variable formula, as you will see shortly: the measure of ability to contribute—am I allowed to say more, Mr. Brau?

MR. BRAU: You may.

MR. FISCHER: I may. A measure of ability to contribute was GDP, and a measure of need was a measure of the balance of payments adjusted in ways that you'll see when you read it.

This did not lead to necessarily a politically correct way of resolving the issue, and I think it will make the point very forcefully that this issue cannot be settled by resort—by hoping that some magician will pull a technical rabbit out of the hat that will enable everybody to go home and resolve very political issues, namely, share of the vote in the IMF on a technical basis. But it was an interesting and a very useful exercise, and we are going to start a work program now to draw the conclusions.

We will not, in fact, need to go very far with this exercise until the next quota increase, which has to be reviewed in 2003. If the world economy stays peaceful, the IMF probably would not need a quota increase then. But, you know, three years is a long way away so we don't know what will happen then. But it could be a while, and the pressure is not to do this in a hurry but to try and do it right.

QUESTIONER: Speaking of the liquidity ratio, you said that it is the highest since the level prevailing before the Asian financial crisis. Could we know what was the level before the Asian crisis, please?

MR. FISCHER: I'm sure Mr. Brau knows, but when I say the highest, it's now because it's higher as a result of Mexico. It wasn't—153 percent was not the highest ever. One hundred and seventy-eight percent.

MR. BRAU: Just to supplement that, there is a figure in the Annual Report on page 65, and you will see there that in 1998, which was after the IMF began disbursing to some of the Asian countries, the liquidity ratio was down to 30 percent. In 1997, it was—so this is before the Asian crisis—roughly 50 percent. As Mr. Fischer mentioned, now it is 178 percent.

MR. FISCHER: And the answer to your question, on page 65, with our new and improved graphics, it's clearly about 165 percent in 1994 before the Mexican crisis.

MR. HACCHE: Next, please?

QUESTIONER: Our friends in the protest community enlivened the meetings during the spring. How concerned are you about what will happen in Prague and that whatever happens there will overshadow this effort to get out the new IMF image? And could you talk about any contingency plans that you might have for those meetings?

MR. FISCHER: You know, obviously there's a concern and great uncertainty about what is going to happen. We've been working intensively with the Czech authorities, as have our colleagues in the World Bank, and they are doing an enormous amount of work to try to make sure that this situation does not lead to violence or massive disruptions of the meetings.

It's very hard to say what is likely to happen. It depends on who comes and what their goals are. And there's a concern. You know, we are trying to move in the direction of making globalization work, of making the global economy work for all, and I think that what we're doing is very constructive. And holding up these meetings doesn't exactly advance the goals of making globalization more manageable, and it isn't going to stop globalization either. We need to make globalization work, and I don't think that stopping the IMF or the World Bank will achieve that. It will also damage the efforts to move ahead with initiatives that many of the demonstrators rightly support, like the debt reduction initiative.

As to contingency plans, I am not handling the plans for the meeting, and if there were contingency plans, I wouldn't tell you and I don't know. And I have great faith in the Czech authorities, given that my colleagues have been in very close touch with them and have spoken to them about what they're doing.

MR. HACCHE: Next, please?

QUESTIONER: My question refers to a comment made by a senior official of the IMF recently that some of the countries—some of the emerging market economies that are not oil-producing need special consideration in the current climate, with the current oil crisis. And to me that immediately brings to mind the case of Ukraine. So my question to you: Do you see any possibility of Ukraine getting any IMF money by the end of this year?

MR. FISCHER: I thought we were going to have a big philosophical question as you got going, but there you are.

I don't know whether a mission is in Kiev now or just come back, but we are discussing with the Ukrainians how to move ahead after the exhaustive inquiry into what happened with the reserves, on which we reached our conclusions last week. We're now in a new phase.

We shouldn't rule out the possibility of reaching an agreement, but there's a lot of work to be done. We need to have a variety of macroeconomic measures agreed, including the budget for next year, and there are also some structural measures that need to be looked at, including in the banking sector.

What I can safely say is that it isn't precluded, but I can't give you probabilities at this moment.

QUESTIONER: You talked about the review of facilities and going back to basics, and I was wondering how you will relate this return to basics with reviewing the Contingent Credit Lines. In Latin America the countries are in such different situations, like Mexico and Argentina, that have expressed interest in this line, and I was thinking of this overall revision. How do you view that facility and toward what objectives it should be directed?

MR. FISCHER: The CCL is directed very much to dealing with the consequences of contagion. If a country gets into trouble for reasons that are driven by its own policies and not driven by something outside, it is not eligible for the CCL. That's the first item. So it's going to operate in generalized crises or in trying to prevent crises becoming generalized.

That doesn't mean it couldn't apply to countries in different situations with different types of policies. Our basic requirement is that there be good macroeconomic policies—monetary, fiscal, a strong financial system—and cooperative relations with the private sector, and making progress in the implementation of relevant standards and codes.

You know, situations of countries could differ a great deal in many regards, but those are the things we'll be looking at. And it is a facility designed for those who we believe are in fundamentally good shape and who are not likely to get into trouble as a result of their own policy mistakes. And we'll have to make that judgment as this begins to work.

We hope that the changes we're making now—literally today or tomorrow is possible, and by Prague, anyway—will make this a more usable facility because it is a very important facility philosophically as well as in practice.

It moves the IMF from always responding in the event of a crisis to trying to provide facilities that will make a crisis less likely. So it's moving us in our lending activities from crisis response to crisis prevention. And in that sense, it's a valuable supplement to surveillance, and it's important. I hope we make it work.

MR. HACCHE: Next, please?

QUESTIONER: Mr. Fischer, the G-7 Finance Ministers in Fukuoka were talking about the idea of reducing any incentives or increasing the disincentives for countries to be long-term borrowers from the IMF. Mr. Köhler made some comments on that at the National Press Club in August.

Where do discussions on that issue stand?

MR. FISCHER: It is part of the ongoing discussion on the review of facilities. I've talked about the CCL at some length, but that's another element in the discussion on the CCL and other facilities taking place now. There is no question that if there is an agreement—and I expect there will be—it will include measures designed to reduce the length of usage of IMF facilities by countries that are in a position to repay.

MR. HACCHE: Next?

QUESTIONER: Mr. Fischer, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the handling of financial crises. There's a chapter in the report, and while you've been talking, I've been looking at it briefly. It looks as if—but please tell me if I'm wrong—on lot of the key questions that were raised after Asia about how to handle these things in the future and some suggestions on handling them, a lot of the key questions beyond increased surveillance and transparency are still unresolved. There are small fixes in the architecture that people have agreed to, but in terms of large structural changes, moving walls and beams and struts, no one is yet ready to make a commitment.

Could you tell me, if you could step back, what philosophically is the disagreement here that's preventing major architectural changes?

MR. FISCHER: I'm not sure what the disagreements are. Let me suggest, though, that there really are major changes in the emerging market countries in particular. Then see if I can answer your question by talking some of this through.

I actually, when I wake up in the morning and ask myself, "Well, how serious have we done anything?" which is your question, end up saying, "yes." And the factor that I place a lot of weight on is the change in exchange rate regimes for emerging market countries.

We knew for a long time that at the theoretical level you couldn't have a fixed exchange rate, free capital flows, and a monetary policy that was directed to domestic objectives. That was known since 1960 as a result of work done in the IMF by Robert Mundell, but you never knew the consequences. That is now very firmly understood. You peg your exchange rate,and that's what your monetary policy is about; it doesn't have any freedom to do anything else, so it doesn't get directed to domestic policies. Or you let the exchange rate float.

That removes a major inconsistency, an inherent contradiction in the system of trying to do all three.

It makes a very, very big difference. It doesn't preclude crises, but it precludes a peculiar, particular class of crisis of which we had several in the period 1994 to 1999.

That's very big. I don't know whether you call it architecture or what, because you can't require a country to do one thing or the other. But countries have learned.

Then I believe the work on financial sectors is very important and is making a major difference, and you do see countries strengthening financial systems.

Now, you say, well, it's not really happening, and everybody grumbles about what's happening in Asia. It's one of those glass-half-empty, glass-half-full cases. There is a lot going on. It hasn't gone far enough, it hasn't gone fast enough, but we're in a very different situation.

Third—and it seems a triviality, but it isn't—the degree of information that is out there about what is happening in countries is completely different. We may have to pinch ourselves to realize that we did not know what the reserves were in Mexico in November 1994 because the last number we had was, I think, over three months old. That is not going to happen in future. Countries are not going to be able to get into that position. It was the same in Thailand and in Korea in 1997, where the reserves just ran out and there was no information on it. We're in a very different world of transparency now, and it makes a difference to the way in which markets work. It's very, very important.

And then I could go on with a lot of other initiatives. Now, these may not look like moving walls, and I'm not sure whether moving walls is what you're supposed to do.

And there are things where there's still controversy. Private sector involvement, I think we've reached a pretty good position. I believe what we did in Ecuador is different than anything we would have done before and that it helps the private markets understand how future crises will be handled.

There is a difference— I suppose it's a difference—the only one I could really identify in response to your question, and I'm just sort of thinking it through as I talk. I would guess it's a set of beliefs about how far you can go in controlling capital flows and that there are some who believe in a minimum of intervention and others who believe that considerable intervention and regulation is necessary. But even there the differences have been narrowed. Controls on capital inflows are widely accepted as being helpful, even as Chile has moved away from the controls that everybody said were so good. Chile has decided not to continue to use them.

On hedge funds, as you recall, there was a tremendous outcry about the role of hedge funds. Well, in some ways it's being resolved by the diminution in the role of hedge funds, and you now have people complaining there's no liquidity in the markets because where are the hedge funds?

So there's been a lot of change. How safe should you feel? You should feel safer. Should you feel safe? No, because you always are in danger of solving the last crisis and putting in place the measures that will deal with that and then having something different come up. So you've got to stay on your toes, and as much as you stay on your toes, you'll miss something. That's why the Managing Director has been very careful to keep reminding us—and he should—there will be future crises, and we need also to have the capacity to respond.

QUESTIONER: Do you feel that it might be easier for the IMF to work in a crisis environment if it was recognized as the lender of last resort?

MR. FISCHER: You know, there are several definitions of lender of last resort. I'm telling you the contents of a paper I wrote, so you probably know all this.

There is one key characteristic of a domestic lender of last resort the IMF doesn't have. It cannot produce the thing that people want to borrow. In most countries, that's the domestic currency. The central bank can manufacture that in infinite amounts just by writing an entry in the books. We can't do that, so we can never be a lender of last resort in that sense.

But a lender of last resort is also two other things: the manager of a crisis and the lender in a crisis, and sometimes a big lender in a crisis. That we can do.

So there's no point in trying to define exactly lender of last resort because it's very emotive. Some people just get upset when you use the words. But I don't think there's any disagreement on the substance. We don't have the resources which would enable us to tell a country: "Oh, well, you need 200 billion? Boom, here's a check." We'll never be in that position, nor should we be, because of the moral hazard issue.

On the other hand, we are recognized as the institution to which countries, member countries in trouble and member countries seeking to help those in trouble, turn when there is a crisis. In that sense, we're the crisis lender and crisis manager.

MR. HACCHE: One more, please?

QUESTIONER: I was wondering if the IMF supports the letter sent by the World Bank to Indonesia about militias in West Timor. And if you do support it, how would that affect any future lending by the IMF to Indonesia?

MR. FISCHER: Obviously, Jim Wolfensohn's letter is important, and we support the general point that he makes about the responsibility for preventing the sorts of incidents that took place there.

Our program will be discussed in the Board today with Indonesia, and as of now, we will have to keep watching what happens in West Timor. It is ultimately a judgment for our shareholders to make as to how they want the institution to react. I think we will watch and see. I'm sure that President Wahid, who in many difficult circumstances has been trying to do what is politically right and reduce violence and areas where there are separatist forces and so on, will do what he can to reduce this. And I would be surprised if there's any sense—I didn't see it in Jim's letter—that he's holding the President responsible for what happened. He's urging the President to take what measures he can to prevent this sort of thing, and I think we're all working in the same direction. So at the moment, we'll just have to follow the situation closely.

MR. HACCHE: Thank you, Mr. Fischer.

MR. FISCHER: Thanks.

(Whereupon, the press briefing was concluded.)

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6278 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |