From Despair to Hope: The Challenge of Promoting Poverty Reduction, A Lecture by Anne O. Krueger, First Deputy Managing Director, IMF

November 17, 2005

A Lecture by Anne O. Krueger

First Deputy Managing Director, IMF

Presented at the Annual Boehm-Bawerk Lecture

University of Innsbruck

November 17, 2005

Good afternoon, distinguished colleagues. First let me thank you Professor Chen for that kind introduction. It is, of course, a great honor to have been invited to deliver this year's Boehm-Bawerk lecture. Eugen von Boehm-Bawerk was one of Austria's most illustrious economists—quite an achievement in a country that has produced so many of them!

Dr. von Boehm-Bawerk did much of his most important and seminal work here at the University of Innsbruck. He went on to serve his country as Minister of Finance, giving him the rare insight into the challenges of economic policymaking that comes from the combination of economic theory and direct policymaking experience.

Dr. von Boehm-Bawerk's many contributions to economic theory are well-known to everyone here. His work on intertemporal valuation, for example, added much to our understanding of resource allocation. And, presciently, he recognized the complementarity of what we now know as macro- and micro-economics. In an 1891 essay, he wrote:

"One cannot eschew studying the microcosm if one wants to understand properly the macrocosm of a developed economy."

I would go further and argue that this applies to all economies, at whatever stage of development and is relevant to some of the issues I will discuss in this lecture.

My focus today is on poverty reduction—and specifically, how to overcome the obstacles that hinder efforts to reduce poverty in the developing world. For those interested, the first part of the title of my lecture comes from a modern Indian writer, Satish Kumar, and is, in turn, derived from the Upanishads.

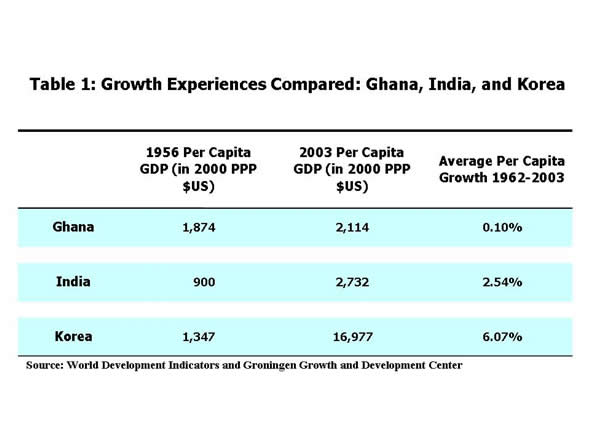

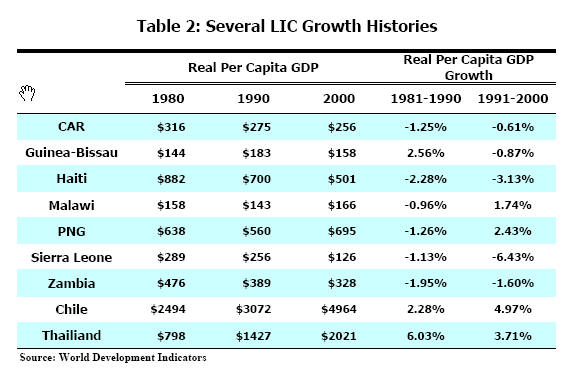

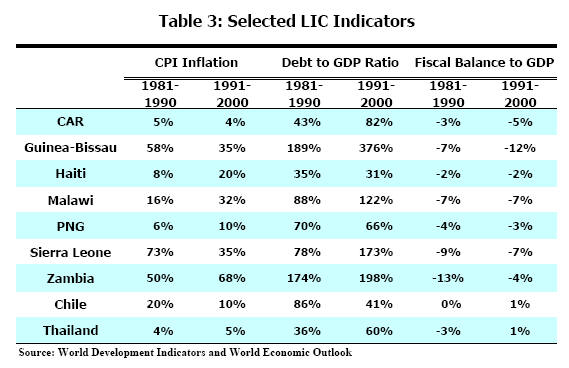

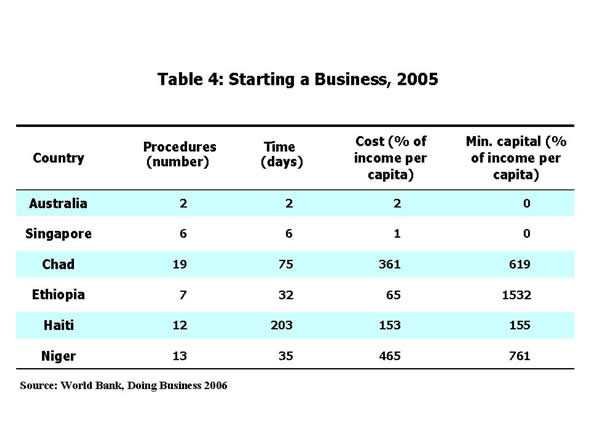

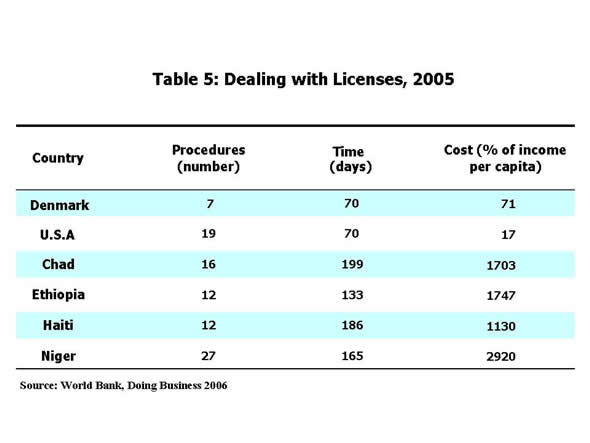

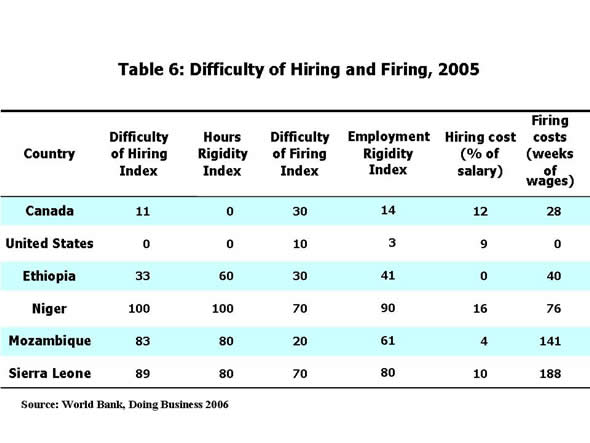

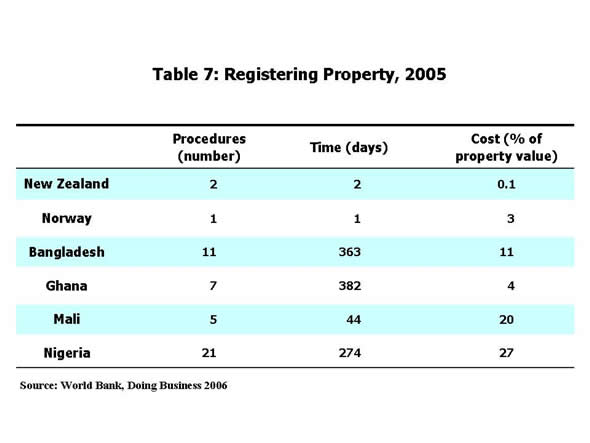

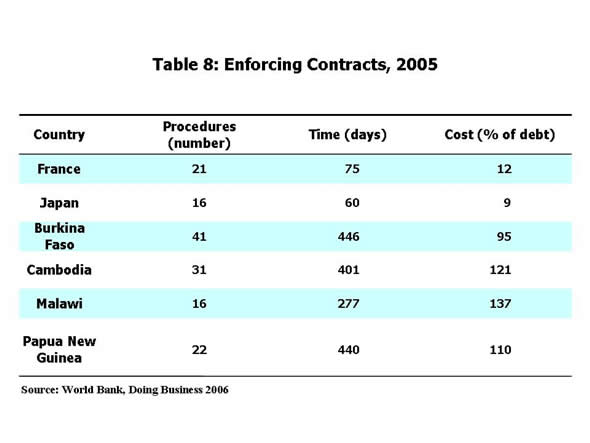

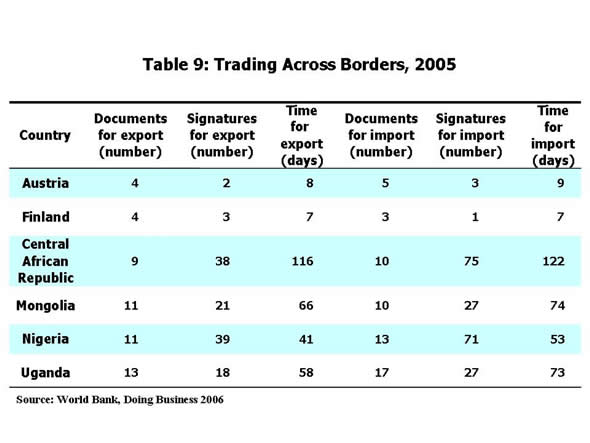

Introduction If, at the end of the Second World War, economists had been given an accurate forecast of the course of the world economy over the next 60 years, they would have disbelieved it. Professor Seymour Harris of Harvard University was a prominent spokesman of the view, shared by the vast majority of Anglo-Saxon and continental economists, that the economic problem confronting the industrialized countries would be "stagnation" and persistent unemployment. And, at that time, the economic challenges facing what were then regarded as "underdeveloped" countries were not seriously analyzed; it was implicitly assumed that their poverty was endemic and little thought had given been to policies that might change their condition.1 Indeed, an underlying premise of global analysis was that the (non-central planning) world was divided into the developed and the underdeveloped countries. That pessimistic view quickly gave way: first to a spate of activist governments attempting to follow "government-led" models of economic growth; and then to the spectacular success of some very low-income countries with unheard-of rates of economic growth achieved largely by reliance on uniform incentives provided to individuals. The first group of these rapidly growing countries, in East Asia, demonstrated the feasibility of rates of growth without historical precedent. They were followed by countries in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. This led to the recognition that low and stagnant real per capita incomes were not inevitable and could be altered. Indeed, new labels—such as "East Asian tigers" and "newly industrializing countries"—were found to indicate that these countries were now inherently different from those "less developed countries" that had thus far failed to achieve reasonably rapid growth rates. Today, the term "emerging markets" is widely used for the large group of countries with generally market-friendly policies whose high rates of economic growth (and associated slowing of population growth) have been sufficient to achieve sustained increases in real per capita incomes for a long enough period so that per capita incomes, while still below those in industrialized countries, are no longer in the abysmal range. Other indicators of well-being, including literacy rates and life expectancy, show a remarkable improvement, and percentages living in poverty have fallen dramatically in these rapidly growing economies. At the same time as the most successful emerging markets experienced growth rates of per capita income previously thought infeasible, the industrial countries experienced a sustained growth rate more rapid than any experienced in the l9th century instead of the anticipated "stagnation". In the second half of the twentieth century, world real GNP undoubtedly grew at a much faster rate than in any prior half century in economic history: the industrial countries also grew more rapidly than they earlier had, and the emerging markets grew more rapidly still. As a result, those in industrial countries and emerging market economies are far better off than they were. But a number of countries failed to grow at all rapidly, and some even regressed. As a result, today, most analysts would recognize at least three groups of countries.2 There are the rich, industrial, countries with very high—and still rising—real per capita incomes. There are emerging markets (or mostly middle income countries) where rapid economic growth has led to much higher and still rising living standards and has significantly altered economic structures and reduced poverty. And there is also a large group of low-income countries, where living standards are not significantly different in many regards from what they were in the middle of the last century3, or, in some cases, are actually below what they were 50 or 60 years ago.4 Economists' thoughts regarding economic policy sixty years ago were also greatly different than those now prevailing. It will be recalled that the Great Depression had led many to believe that governments had an active role to play in many arenas of economic activity, quite aside from those who then believed that the experience of the Soviet Union demonstrated the potential success of government ownership, leadership, and control of economic activity. That thought, too, has changed. The manifest success of the market economies, as contrasted with the breakdown of the Soviet Union, and many other factors have led most economists to reassess the relative merits of markets and state control. And, as experience with economic policy intended to achieve rising living standards for the poverty-stricken in poor countries has mounted, the theory of economic development has also changed. Whereas in the l930s, Pigouvian social welfare functions were thought to provide an analytical basis for economic policy and a rationale for government intervention with taxation and subsidies for disparities between private and social welfare, the experience of the l950s and l960s brought to the fore the notions of second-best, the theory of policy making in the presence of distortions. Primarily with reference to industrial countries, the theory of public choice was developed to raise questions about how, in a democracy, societal decisions were made with regard to economic policy. It brought to the fore the recognition that government officials were not benevolent disinterested social guardians in the spirit of Mill and Pigou, but were rather often self-interested, much the same as the private economic agents whose maximizing behavior had always been assumed to be selfish. But, despite all that, much thought about economic policy is still based, implicitly or explicitly, on a notion of governmental behavior that stands in sharp contrast to that observed in many of the low income countries in the world. Those economic policies are not entirely exogenous either to poverty or to the politics of low income countries. And that is the topic on which I will focus today. The world economy has been amazingly successful in lifting many out of poverty, and economic policy has greatly improved in many contexts. But as yet, the LICs have not achieved the same success as the others. Fifty years ago, some of these LICs had per capita incomes much higher than some now emerging markets. As we can see from Table 1, Ghana, for example, was estimated to have a per capita income of around US$ 1,874 (in 2000 prices at purchasing power parity rates) in l956 whereas India's was estimated to be around $US 900(in the same units) and Korea's was US $1,347. In 2003, the three countries' per capita incomes, all in 2000 prices, were estimated to be: Ghana $2,114 (which is only 13 percent above the level l956); India $2,732 (3 times the level of l956) and Korea $16,977 (nearly 13 times the l956 level). These huge relative changes are accounted for, of course, by greatly differing per capita growth rates: Ghana averaged only 0.52 percent per year over the entire period (and only 0.10 per cent annually from l962 to 2003); India averaged 2.4 percent annually (and 2.54 per cent from 1962-2003); and Korea 6.07 percent over the l962 to 2003 period.  In addition to these large variations in growth rates, another phenomenon occurred: a number of countries experienced periods of a decade or more during which real per capita incomes declined. In some instances, this was due to conflict, but in many cases, other factors (and, in particular, misguided economic policies on which I wish to focus today) were responsible. A prominent example was Ghana: after Independence in 1957, per capita incomes rose for a few years, but then began declining in l964. By l984, per capita incomes were almost 23 percent below their level at Independence. Subsequently, altered economic policies enabled Ghana to achieve better results, although growth has been at moderate rates except for a short period after the start of the recovery in the mid l980s. Lessons from the experience of the emerging markets (and from industrial countries) demonstrate that the poverty and stagnation of the LICs is not preordained or inevitable. And yet, despite the human misery, many countries have as yet been unable to break out of their low level poverty traps. The important question is why, and how the low income countries can achieve sustained growth at a rate sufficient to begin reducing poverty markedly. The international community as a whole has endorsed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which set a number of targets, including (and perhaps most importantly) halving the rate of poverty by 2015. While that goal will almost certainly be achieved globally (based largely on the fairly rapid growth of India and China), there are a large number of countries—in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Central Asia, and elsewhere—where there is little hope of coming even close to those targets on present trends. In this lecture, I will start by providing a very quick overview of why growth is a prerequisite for sustained and quantitatively significant poverty reduction,5 and then briefly sketch some of the characteristics of economic policy in countries that have achieved relatively rapid growth. Then, I shall set forth some of the salient characteristics of economic policies in those countries that have failed to achieve economic growth. That will provide a basis for analysis of what has gone wrong. I will conclude by considering what needs to happen and the obstacles that lie in the path of that turnaround. Growth as a Prerequisite for Poverty Reduction Many well-intentioned persons note that, even in countries where there are huge numbers of poor people, there are also those who are rich. They conclude that the poor could be helped by income redistribution from the rich, and advocate policies such as highly progressive income taxation to achieve that goal.6 Many of these policies were implemented in many now-emerging markets in the l950s and the l960s. Recognition that such policies could neither generate satisfactory rates of economic growth nor achieve any significant reduction in poverty has led most analysts to conclude that the main vehicle for poverty reduction must be growth. To be sure, with economic growth it is important that the poor have access to social and economic services that enable them to become more productive. But successful poverty reduction has to entail concentration on policies that will enable most citizens of society to become more productive. The reasons why redistribution does not offer very much hope for poverty alleviation are several. Fundamentally, when per capita incomes are as low as they are in poor countries, all policy could achieve—even if it did not adversely affect incentives or real output—would be to "redistribute the misery", in the words of Amartya Sen. It is self-evident that, in a country such as Guinea-Bissau, where per capita income is less than US$ 200 per year at prevailing exchange rates and not much more than $700 in purchasing power parity terms, all that redistribution could do would be to insure that everyone was equally poor! Moreover, policies that would even begin to reach such a goal would have strongly deleterious effects on incentives for production and would thus reduce real national product and hence per capita income. If highly progressive taxes on income and wealth were imposed and enforced, there would necessarily be strong disincentives for investment in new, higher, income streams, not to mention incentives for capital flight. In most of the very poor countries, one common characteristic is widespread evasion of government regulations, and it is doubtful whether such tax measures could even begin to be enforced. While tax systems can have elements of progressivity, experience worldwide has led to disillusionment with their potential for achieving redistributive goals. Very few countries have been able to adopt policies that resulted in meaningful changes in income distribution over the medium term, except at enormous cost in terms of foregone growth. And the countries that have achieved very rapid growth have generally had much the same income distribution throughout the process. But that experience demonstrates that, in most circumstances, rapid rates of economic growth are a necessary condition for rising living standards for the very poor. And, if pro-growth policies are undertaken with attention to poverty alleviation—through education, health care, and provision of means for increasing productivity—they are necessary and sufficient. Simultaneously, the disincentive effects on economic activity of redistributive policies (or even heated and continuing debates about them) appear to be much larger than earlier thought. If one accepts the overwhelming evidence—based on simple arithmetic and experience—that redistribution can do little to make significant changes in income distribution without greatly reducing growth prospects and hence precluding longer term poverty alleviation, the alternative is to seek means to make societies more economically productive. That, in turn, translates into seeking means to accelerate economic growth. Economic Policies for Growth Almost any new leader of a country can adopt measures that would stand a good chance of achieving an expansion of real output of more than 5 percent for a year or two. Perhaps the most famous example of that was when Alain Garcia became President of Peru in l985, and ran a highly expansionary fiscal and monetary policy. Real GDP expanded by 12 and 7 per cent in the following two years. But by that time, there was a large current account deficit (which reached 5% of GDP in 1990, the year Garcia left office); Peru had incurred huge foreign debts (foreign debt as a percentage of GDP had risen from 73 in l985 to l65 three years later); and the party had to end. At that point, real GDP fell by 9 and 13 percent in the next two years. While Peru had experienced an expansion of real output in l986-87, there was no sense in which it was "growth": four years later, per capita incomes were lower than they had been at the beginning of the boom. For present purposes, my point is that the sort of economic changes that have occurred in rapidly growing countries have resulted from a period of sustained economic growth, not a one-off experience as can occur with a blow-out fiscal policy (or even improved terms of trade as can happen, for example, with an oil exporter when the price of oil rises sharply). So what is under consideration here is relatively rapid rates of real economic growth—say more than 3 percent per capita—over a period of years. Countries such as India (where per capita GDP has grown at an average annual rate of 4.3 per cent over the decade starting in l994) and China (with a per capita growth rate of 8 per cent over the same period) have significantly increased their growth rates from earlier decades. While not all these growth rates equal the earlier achievements of Korea and the other east Asian tigers, they have nonetheless been sufficiently high to make a significant dent in poverty and to alter the economic landscape in significant ways over one or two decades. To achieve this sort of growth requires policies quite different from the populist expansionist burst. Precisely what the policy requirements are depends on a number of factors, including the existing policy stance at the start of a drive for growth, the level of per capita income at the time policies are geared to accelerate growth, and much more. Indeed, one general lesson of the past half century has been the need for continuous policy reforms in order to sustain growth. Policies that enabled Korea to achieve a l3 percent annual rate of real growth in the l960s—when per capita income was US $850 (in l990 prices) and 75 percent of the population derived its livelihood from agriculture—would not have been sufficient to permit growth in the l990s when per capita income was over $9,000 in the same prices.7 Fortunately, achieving rapid rates of growth does not require "perfect" policies, although it does generally entail the absence of extremely bad policies and improvement in one or more crucial aspects of the policy stance. But when policies are all detrimental to growth, it is hardly surprising that growth rates can be low or negative. That said, macroeconomic stability, a business environment that provides producers with reasonable confidence that they can protect their rights, provision of appropriate physical and human infrastructure, and relatively uniform incentives across economic activities all appear to be necessary for sustained economic growth. Fortunately, it is not necessary that a country immediately jump from a highly unsatisfactory environment to one comparable to the advanced countries; but there is a necessary minimum and, as growth proceeds, it becomes more difficult to sustain without improvements in these dimensions. An overarching issue, and one central to this lecture, is the relation between the public and the private sector. It permeates each of the "essentials" enumerated, but a convenient starting point is that increases in output per head—and that is the metric that is closely aligned with increases in real per capita incomes and living standards—occur when people have more or better equipment with which to work and/or because people find ways to increase their output (their productivity) with the equipment they have.8 Better equipment can take the form of the public infrastructure (better roads which cut the cost for the farmer of transporting his crop to the market) or of private goods (such as refrigerated trucks which enable the farmer to bring his crop to market with less deterioration en route or even to produce higher-valued crops that could not earlier reach the market). Increases in productivity can arise from public sector activities (of which agricultural research and extension is an important example) or from private activities (such as learning to grade crops, or apply fertilizer in the appropriate quantities and at the right times). As these examples illustrate, public and private activities are both essential for rapid economic growth; but for now the important point is that most private acquisition of equipment and effort at learning more productive ways is undertaken in the expectation that it will benefit the individual undertaking it. Thus, the incentives confronting individuals are an important determinant of their choice of economic activity. The public sector plays a crucial role in affecting these incentives, a theme to which I will return later. For present purposes, the proposition that incentives are important is all that is necessary to outline the reasons for the crucial importance of the issues mentioned earlier. Macroeconomic stability is important for a number of reasons. First and foremost, when individuals cannot know what the rate of inflation will be, they are reluctant to invest long term, and at any event lenders are unwilling to lend longer term except at very high interest rates. If inflation is expected to be high (say double digit or more), it makes sense to invest in very short term projects, including even inventory accumulation. The fact that inflation is seldom high without being variable adds an additional element of risk for those contemplating longer-term investments, as even variable yield loans require borrowers to repay a higher fraction of the principal in early years of the life of the loan (because part of the nominal interest rate is the repayment of capital). Perhaps equally important, even in periods of high inflation, not all prices move synchronously. In consequence, entrepreneurs have difficulty discerning whether their ability to increase their price is simply a consequence of inflation, or whether it is partly or entirely a relative price signal. Responses to shifts in relative prices are therefore more sluggish than in an environment where the price level is fairly stable. But perhaps even more important, inflation does not occur in a vacuum: usually it is in significant part a result of expansionary fiscal policy financed by deficits in government budgets. Fiscal deficits, in turn, are by definition the use by the public sector of some resources additional to those generated by government revenues.9 They can be financed by the issuance of bonds (which raises interest rates and thereby makes private investment less attractive), or by money creation and the inflationary consequences just mentioned. Either way, there can be a "crowding out" of the private sector. Such policies, as happened in Peru with the consequences I described earlier, can generate an increase in economic activity for a period of time, but normally result in contraction or slower growth thereafter. But I already stressed that incentives for private sector economic activity need to be appropriate for solid and sustainable economic growth. First and foremost, incentives should be such that they reflect to individuals the societal benefits of alternative economic activities. Thus, businessmen should be confronted with the relevant trade off between producing import-competing and exportable goods, which in almost all cases is the relative world prices of these goods. They should also be in an environment where they face competition—another important role for international trade. But incentives are equally important for decisions about inputs: whether to hire labor or capital, what crops to plant, and so on. In many developing countries, well-intentioned politicians have enacted labor legislation which provides job protection for workers, high wages, education and training for their families, and other benefits. The consequence of these incentives has been relatively high wages (by the standards of the country) for those employed in the formal private sector, but slow rates of increase in employment opportunities, while an informal sector coexists with much lower wages. Simultaneously, businessmen tend to employ more capital intensive techniques of production than they would were the labor market not so regulated.10 The same sort of distorted incentive occurred when governments maintained constant nominal exchange rates in the face of inflation rates higher than those in the rest of the world, and rationed "scarce" foreign exchange. Ironically, the attempt to make imported goods deemed essential for development cheap in fact resulted in waste for those lucky enough to receive import licenses. High up on the list of important incentives is the so-called business environment. Once thought is given to the components of that environment, it is evident why this is so important. First and foremost, if governments are regulating many or most aspects of economic activity which require a permit or other government permission, there is a strong temptation to favor those who are politically well connected. When that happens, the incentive for the businessman is to use his resources to garner political connections, rather than to try to lower costs among the resources he is already employing. Hence, an environment in which an entrepreneur can readily obtain his needed inputs (at prices that reflect their relative value in other lines of activity) is essential for satisfactory economic growth.11 A related prerequisite pertains to the existence of a level playing field: if there are, or may be, public enterprises entering a given line of economic activity, it would be foolhardy for many private sector entrepreneurs to enter it, if only because of the uncertainty surrounding the extent to which government regulations will favor the public enterprise. If the public enterprise is de jure or de facto tax exempt; if the public sector enterprise will receive preferential treatment in the allocation of scarce goods (such as imports, priority for shipping goods, or maintenance of power supply when private concerns are confronted with rolling power outages); or if prices of public sector enterprises are likely to be suppressed in an effort to avoid inflation: rational entrepreneurs will usually avoid investments in activities competing with those enterprises. But there are other, equally important and related, aspects of the business environment. Perhaps most important is the ability of an individual to have security of property rights. That relatively easy phrase covers a lot of ground: it is essential that those writing contracts have confidence that they will be enforced; that, in turn, requires a commercial code and a legal system that functions well in the context of the rule of law. Obtaining deeds for land must be feasible and not too difficult, and transferring property to new owners upon sale must also be relatively straightforward. Provision of a favorable business environment is certainly a major responsibility of a government committed to achieving sustained and rapid economic growth. I shall return to experience with these issues after discussing infrastructure and its role. Even if all the factors enumerated so far are in place, little private sector activity will be generated if the societal infrastructure is inadequate. That infrastructure can be conveniently thought of as having two main parts: the physical and the human capital. Turning to physical capital first, it is evident that peasants will not decide to grow export crops unless the price they receive for those crops is attractive. Yet, in the absence of transport modes that enable the shipment of these crops to the ports and the sufficiently economic operation of ports to render the farm gate price of the commodities adequate, there will be little production. There are recorded instances in which the cost of shipping the commodity, first to port and then overseas, exceeded the price of the commodity in the importing country! Very bad roads (or railroads) raise the cost of transport both by increasing wear and tear on vehicles and by increasing the time required to get to destination. Delays in transferring the goods to ships (because of port congestion, inadequate equipment, or even because of required paperwork) further increase costs. An improved road system can be thought of as a generalized increase in productivity to the extent that it enables local producers to obtain better returns for their products. But other aspects of physical infrastructure are essential as well. Telephony, power supply, irrigation, and even mail service, are all important. Their availability and cost are both determinants of productivity of private sector economic activity. Recently, internet availability and mobile phones have reduced the costs of poor telephony; and many producers in developing countries routinely install (high-cost) generators to back up for irregular power supplies (which of course raises the cost of investment). But dependable supplies at reasonable prices for these elements of infrastructure are again crucial determinants of productivity; improvements in these services enable more productive use of private resources and hence have the potential for raising growth rates. Investment in human capital is also important for growth and for productivity. As young people receive more and better education and training, their potential productivity as members of the workforce increases. As that happens, employers can afford to pay higher wages and simultaneously find it profitable to hire more workers. Growth Failures With that background, attention can return to the growth performance of those countries that have been unable to achieve rapid and sustained increases in per capita income. Some tables tell much of the story. Table 2 shows the growth rates for seven low income countries (LICs) for the period from 1980 to 2000. All these countries saw declines in real incomes over one or both decades. Compare that with the performance of the other two countries, at the bottom of that table, Chile and Thailand. Both are middle-income or emerging market countries.  Table 3 provides data on the fiscal deficits, inflation rates, and debt/GDP ratios for the same nine countries over the same period. As can be seen, among most of the low income countries, inflation was high and or rising. So were the ratios of external government debt to GDP. And in most cases the fiscal deficits were high in both decades.  Compare that performance with the other two countries on the table: Chile and Thailand, both middle income countries pursuing reform programs. And, as Table 3 also shows, over the same two decades, Chile lowered its inflation rate, and halved the debt to GDP ratio while pursuing a prudent fiscal policy. Thailand experienced relatively low inflation throughout the period and although its debt to GDP ratio rose in the 1990s, it maintained a prudent fiscal stance. I mentioned the importance of the business environment in the context of fostering growth. A closer look at some indicators of the business environment drives home this point. Table 4 shows, for some low income and advanced economies, the number of procedures required for starting a business, the time it takes to start a business, the cost and the minimum capital required as a percent of per capita income, as of January 2005. In Chad, for example, it takes l9 procedures and 75 days to start a business at a cost equal to 3.6 times per capita income, and with minimum capital of 6 times per capita income.  Table 5 gives some indication of the costs of carrying on an established business. In Chad, l6 are procedures required to get a license, taking an average of 199 days, and costing l7 times per capita income. On that ground alone, one would expect doing business in Chad to be high cost and to be confined to activities in which profitability could be expected to be very high, as for example in petroleum.  Table 6 gives data for a different group of countries on the ease of hiring and firing workers. For this purpose, the World Bank has constructed an index of difficulty (which can vary depending on the types of procedures that must be followed), with 0 being least difficult and 100 most difficult. These indices for hiring and firing are shown along with data on the number of weeks of salary that must be paid if a worker can be fired at all. In Mozambique, for example, the difficulty of hiring index is 83, the difficulty of firing index is "only" 20, but a laid off worker must be paid 141 weeks of salary! Contrast these numbers with those for the US and Canada, in any of the dimensions measured.  There are other indicators that tell the same type of story. Table 7 shows that to register property in Ghana requires 7 procedures; it takes an average or 382 days; and costs about 4 percent of the value of the property. In Mali, there are fewer procedures (5) and it takes only 44 days; but it does cost 20 percent of the value of the property. By contrast, in New Zealand, there are 2 procedures, it takes 2 days, and the cost is 0.l percent of the value of the property. When it takes more than half a year (or even several months) to register a property deed, it is not surprising that costs of doing business are high.  Contract enforcement, which is crucially important, can be equally onerous. Table 8 provides data on the number of procedures, the time, and the cost as a percent of debt, of contract enforcement (when it is possible at all). In Burkina Faso, there are 4l procedures, the average time required is 446 days, and the cost is 95 percent of the debt to be collected. One wonders why any rational person would even attempt to collect, but that in turn raises questions as to whether contracts would even be used in these circumstances.  The number of documents required for export or import, and the number of days required, is another disincentive in many countries. Table 9 gives some illustrative data. In the Central African Republic, there are 9 documents (requiring 38 signatures) required to be obtained prior to exporting, and it requires an average of 116 days—the numbers and the time are even slightly longer for importing! In Nigeria, 11 documents are required (needing 39 signatures), taking an average of 41 days to obtain them, again with even greater delay and numbers on the import side. By contrast, Finland has 4 procedures (with 3 signatures) taking 7 days for export! For some goods, the difference in time delays alone would be sufficient to preclude exports from low income countries.  Taxes and procedures for engaging in foreign trade are equally encumbered by government regulations. In some countries, the taxes legally payable as a percent of gross profits are more than 100 percent!12 But even in most low-income countries where they are not that egregious, they certainly serve as a disincentive. In addition, the time spent to negotiate with government officials and pay taxes can be onerous and must certainly serve as a disincentive for small business. It is estimated that in Ukraine, it takes 2185 hours to accomplish the payment of taxes!13 In addition to the business environment factors documented by the World Bank, poor infrastructure has served as a strong disincentive, as already mentioned, in many low-income countries, and need not be further discussed here. But there is another crucial point: that is, that in countries where there are multiple delays, numerous requirements and procedures, and regulations surrounding economic activity, the scope for bribery and corruption is commensurately expanded. Some sorts of bribes are routine and largely offset by under-pricing of services, as for example when railway clerks accept small fees for immediate shipment of freight when average delays are several weeks. But others, such as those that influence judges' decisions, those that avoid the payment of high taxes, or those that secure a government contract for a high-cost firm, can greatly influence resource allocation, or more precisely, misallocation. In a country where it routinely requires l0 percent or more of the contract price to be paid to a government official, the cost of infrastructure projects is accordingly increased. With a governmental budget constraint, that in itself reduces the physical investment in infrastructure. The same sorts of issues arise in connection with provision of electric power, of education, and health services. But enough has been said to indicate that the sorts of economic policies prevailing in many low income countries can go a long way toward explaining their failure to grow more rapidly. Virtuous and Vicious Circles What I have sketched out here is a circumstance in which there is massive government failure: usually economic failure brings with it political failure, but that is beyond today's story. But to the economist's lexicon of market failure must surely be added the notion of government failure, when economic policies (often adopted in the expectation—perhaps false—of achieving political ends) are inconsistent with even modest growth prospects. When government policies entail high-cost inefficient public sector enterprises,14 regulations and controls over private sector activities, inefficient physical infrastructure, and a failure to deliver health and education services to the population, economic growth is necessarily low, if there is not economic decline. But the failure to deliver an environment or the public services conducive to growth also results in an erosion of public support for the government. But at the same time, the self-interest of politicians and bureaucrats dictates their behavior, as the theory of public choice has taught us. In discussing economic policy, it cannot always be assumed that governments are behaving as benevolent social guardians, that governments are monolithic and unified in their motivation and behavior, nor that any notion of Benthamite social good constrains behavior. The result is a vicious circle: low growth induces political leaders to seek support through the provision of short-term "favors" to essential support groups. These "favors" can be the very licenses and placement at the heads of queues (or exemptions from onerous regulations) that account for slow growth or deterioration in the first place. But, once favors have been granted, maintenance of political support often requires further favors the next time around. Subsidies of food for the urban poor are no longer enough, and subsidization of power begins (or, at the very least, power rates fail to increase when power costs increase with inflation). More relatives of constituents must be placed on state enterprise payrolls (with attendant increases in losses and further declines in productivity) or in government offices. Those actions in turn result in further reductions in the growth rate or absolute falls in output. Either way, the vicious circle gets worse. By contrast, in economies where per capita income is growing rapidly, politicians may still need to do some favors, but much political support can be, and is, generated by the fact of rising incomes themselves. Politicians' and bureaucrats' self interest corresponds more to the social good than in failing states. That enables politicians to focus much of their activity on growth-enhancing investments, with perhaps a longer time period before citizens benefit, but with a surer payoff in terms of growth and rising per capita incomes. Thus, once growth accelerates, a virtuous circle can result. More rapid growth and rising living standards generate more political support, which in turn enables more attention to growth-enhancing activities, which in turn can support more growth. Enough has been said, I hope, to convince of the importance of economic policies as a major explanatory factor in the failure of some countries to grow and their continuing status as low-income countries. When governments adopt policies to regulate and control, in ways that provide private incentives for economic activities that are not consistent with rapid growth, economic growth is negatively affected. And when those policies become sufficiently detrimental, little growth can occur until they change. If the bad news is that economic policies can thwart successful economic growth, the good news is that there are examples of countries that have sustained high economic growth. Clearly, this has entailed economic policy reform and a different set of policies. An important, and as yet ill-understood question, is what, if anything, can generate reforms. Some countries have turned their economies around: Chile, China, India and Korea, among others, come to mind. In those countries, perceived economic failure resulted in a major shift in course, and recognition that the "bad old ways" were not delivering. There are other, more recent, examples of countries—Turkey springs to mind—where the need for far-reaching reforms has been recognized and where, as a consequence, significant progress has been made in delivering macroeconomic stability and more rapid growth. It is far beyond the scope of this lecture to delve into the reasons why some leaders embrace reforms, nor what determines the timing or breadth and depth of reforms. Suffice it to say here that reforms are, and will remain, absolutely essential in low-income countries if they are to achieve satisfactory rates of economic growth. The role of the international institutions Here, the international institutions have an important role to play. In working towards meeting the Millennium Development Goals, a major challenge for the international community is to find incentives and policies that will encourage economic policy reform. This is an area where the International Monetary Fund, often working in close co-operation with the World Bank, is already very active. The Fund's close working relationship with its shareholders includes annual surveillance of all 184 member countries. This gives the Fund a unique insight into economic policymaking. The institution's cross-country expertise means that Fund economists have first-hand knowledge of what works, and what doesn't. The research department makes full use of this cross-country expertise and this is one of the ways in which the Fund's research activities place it at the cutting edge of the research agenda in this area. The combination of research and surveillance enables the Fund to advance powerful arguments in favor of economic reform. The Fund's work with its low income members extends well beyond argument, advice and persuasion, of course. It includes the provision of technical assistance, or TA, to countries seeking to implement reforms. TA now accounts for a significant element of the Fund's work, and ranges from assistance in improving customs procedures or tax administration to the management of monetary policy as more and more countries recognize both the importance of macroeconomic stability and the role within that of an efficient public sector. Helping countries to improve tax collection procedures, for example, can significantly raise the revenue stream from any given tax rate; lowering tax rates can also raise revenues by acting as a disincentive for people to participate in the informal sector of the economy. Streamlining customs procedures can help governments create a more business-friendly environment. When appropriate, the Fund is also able to offer low income member countries financial assistance, both to deal with short-term balance of payments crises and to buttress policy reforms, including through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility. The Fund has also recently agreed on a new facility, intended to help countries adjust to external shocks. But at every stage, the Fund's role is one of supporting the economic reforms needed to deliver macroeconomic stability without which more rapid growth and, in turn, poverty reduction, will prove elusive. Reforms that have no internal momentum have only limited prospects for successfully raising stagnant or declining living standards. Conclusion Let me briefly conclude. Perhaps more than ever before, there is a widespread recognition among economists and the policy community that economic growth—rapid and sustained economic growth—is a vital prerequisite for poverty reduction. There is also a broad consensus that macroeconomic stability is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for achieving rapid and sustained growth. Around the world we are able to see evidence of the benefits of policies aimed at delivering macroeconomic stability and accelerating growth. In the past six decades we have witnessed the remarkable success of many countries that have undertaken wide-ranging economic reforms and where the pursuit of pro-growth policies has permitted rising living standards and declining poverty rates. There is always more to be done: economic reform is an ongoing process. But the biggest challenge facing the international economic community is how to promote policy reform in those countries where progress has been slow or non-existent-or where living standards have actually fallen. Without reform and growth in these countries, the prospect of their meeting the Millennium Development Goals will be very poor. We have to find ways of developing incentives that will trigger the necessary reforms. We can see the benefits of turning the vicious circle into a virtuous one. We need to ensure those benefits are extended to all the world's citizens. Thank you.

1 The first major academic article to focus on the problems of the "underdeveloped countries" was by Paul Rosenstein Rodan, "Problems of Industrialization of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe", Economic Journal, Vol. 53, June-September 1943. 2 Many might recognize a fourth group - those economies in transition from central planning. For many purposes, that distinction is important, but it is not central to the analysis here. 3 For many purposes, other distinctions are employed. Some analysts refer to the "bottom billion"—implying the countries with the lowest real per capita incomes. Others differentiate the "poorest of the poor", the countries with the very lowest per capita incomes. There is also a group of "highly indebted poor countries" (HIPC) that have been the focus of attention because of their low incomes and high unsustainable debt levels. 4 Even in many of those countries, there have been significant increases in life expectancy and improvements in other indicators of economic well being such as literacy and infant mortality. 5 Some authors have focused on reducing inequality of the income distribution as a key to poverty reduction. While strong arguments can be made that reducing inequality in some countries may itself permit more rapid growth (as for example by focusing more on improving educational attainments and health status of the poor), it is generally accepted that the extent of poverty reduction that can occur in very poor countries is highly limited unless growth accelerates. If growth accelerates and income distribution does not worsen, it is evident that the poor will share in the growth. And changing income distributions in ways that are consistent with growth normally can happen only slowly and in relatively small amounts. 6 It is likely that some of the support for government ownership of enterprises was based on the same logic, under the idea that the ownership by the rich of the means of production was what made them rich. Suffice it here to note that those state enterprises that did not have monopoly positions were usually loss-incurring or made very small profits relative to capital invested, and that most analysts would now recognize the inefficacy of SOEs for either growth or income distribution purposes. 7 One of these policies was credit rationing. In the l960s, when exports were 3 percent of GDP and imports were 4 times that, the government directed credit to all exporters. Since the economy had been so heavily distorted toward import-competing activities, credit rationing by and large resulted in an allocation of new resources that probably had little inefficiency (or the economy would have grown even faster!). But by the l980s and early l990s, the Korean economy was much more differentiated, and credit rationing no longer worked; indeed, falling real rates of return to bank assets were a major factor in the Korean economic crisis of l997. 8 In principle, per capita incomes also rise when the terms of trade improve. But those increases are not sustained, and are very often reversed. No country has achieved sustained growth based on continuing improvement in its terms of trade. 9 Most governments have fiscal policies which result in a decrease in revenues and increased expenditures when economic activity is below potential, and the reverse in times when economic activity is buoyant. Such a set of policies results in structural fiscal balance, in the sense that the budget is balanced over the business cycle. It is structural balance to which I am referring above. 10 In the l950s and l960s, governments in many developing countries attempted to keep interest rates very low (and usually below the rate of inflation, thus yielding a negative real interest rate). Because of the high cost of labor due to labor laws, as well as the relatively low cost of capital, very capital intensive techniques of production were employed in countries where all recognized that capital was the relatively scarce factor of production. Negative real interest rates increased the demand for domestic credit, thus further fueling inflation. In more recent years, the economic costs of negative real interest rates have generally been recognized, so that the "distortions" in the factor market generally result more from favorable labor protection laws rather than from suppression of interest rates. 11 This is part, but only part, of the reason why corruption is deemed to undermine prospects for economic growth in many countries. 12 The World Bank (2006) reports that taxes as a percentage of gross profit are l2l percent in Belarus, l35 percent in the Democratic Republic of Congo and 173 percent in Burundi! 13 There can be similar distortions in middle-income countries, but there are two broad differences. First, while one can find egregious delays and procedures, they normally pertain to fewer aspects of the business environment. Second, in most middle-income countries, the cost of these business unfriendly regulations is increasingly apparent and they are gradually being removed. 14 Time has precluded a discussion of the economic effects of a large PSOE sector. But in some countries, politicians have used PSOEs to hire friends and relatives, to locate in uneconomic areas, and otherwise to become very high cost drains on the government budgets. The fiscal impact has become significant in a number of countries, quite aside from the effects on potential competition from the private sector discussed above. |

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6278 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |