Speech by IMF First Deputy Managing Director John Lipsky at the Die Zeit Conference

September 9, 2008

Speech by IMF First Deputy Managing Director John LipskyAt the Die Zeit Conference in Frankfurt, Germany

September 9, 2008

| Download the presentation (608 kb PDF) |

Introductory Remarks

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. It is indeed a pleasure to address this distinguished audience.

The global economy is facing its most difficult situation in many years as we grapple with the financial crisis that erupted last August together with the impact of high commodity prices. Global growth is slowing markedly, following more than four years of strong expansion, while inflation has risen to rates not seen in a decade, especially in emerging economies. Policymakers across the world are faced with the difficult challenge of nursing their economies through a period of tight credit conditions and higher inflation.

Against this backdrop, I will focus my remarks on a few major themes.

• First, prolonged financial strains and still high and volatile commodity prices constitute major global shocks that raise risks of serious "second-round" effects-risks that policy makers will need to contend with.

• Second, while the challenges at hand are daunting—including restoring confidence in the financial system and addressing the interplay between the inevitable financial market deleveraging, tighter credit conditions, and growth—sound policy options are well within reach.

Finally, tackling the immediate challenges—supporting growth and restoring health to the financial system, while keeping inflation at bay—should be viewed against the backdrop of a rapidly changing global landscape, in which emerging economies are increasingly taking center stage. In other words, consistent policies will be needed in all the major economies, if we are to return to the solid growth and low inflation that characterized the best years of this decade.

I will begin with a brief overview of the global economic outlook. Then, I will focus on the continuing financial crisis, discussing what it implies for the world economy, and address the key policy challenges that we face.

Global Outlook

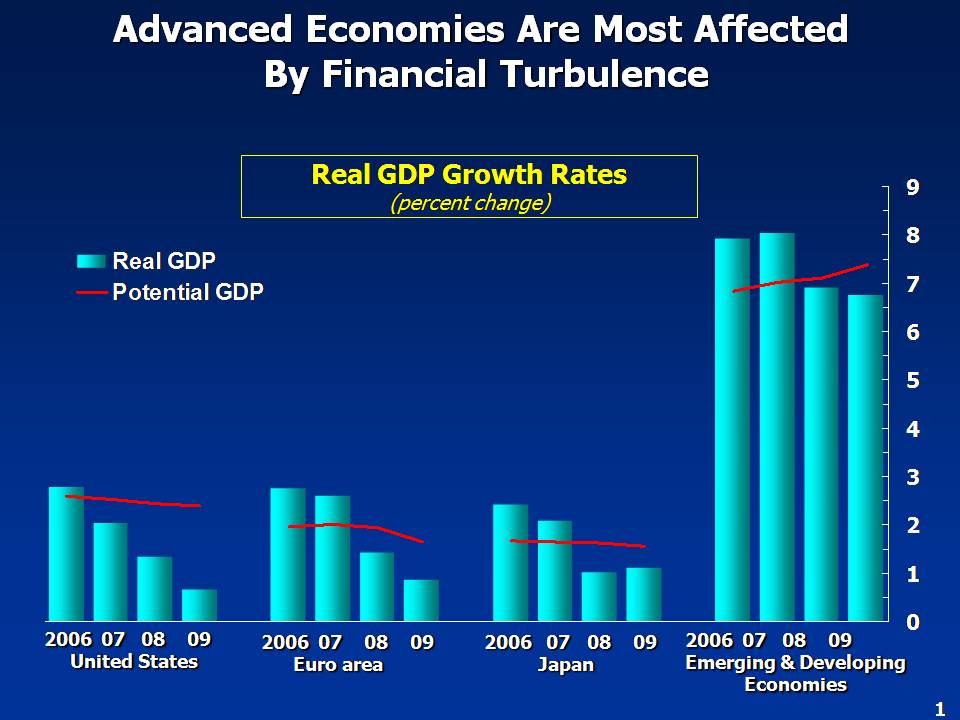

Against the backdrop of protracted financial strains and dramatic surges in commodity prices, the global economy is confronted with its most difficult set of circumstances in many years. Following a remarkable five-year span of strong expansion, global economic activity is decelerating markedly. The growth slowdown originated in the United States, and has clearly spread to Europe and Japan. And advanced economies, in general, face a spell of growth well below potential, as they grapple with ongoing strains from the financial crisis that began a year ago, as well as high oil prices and weaker external demand.

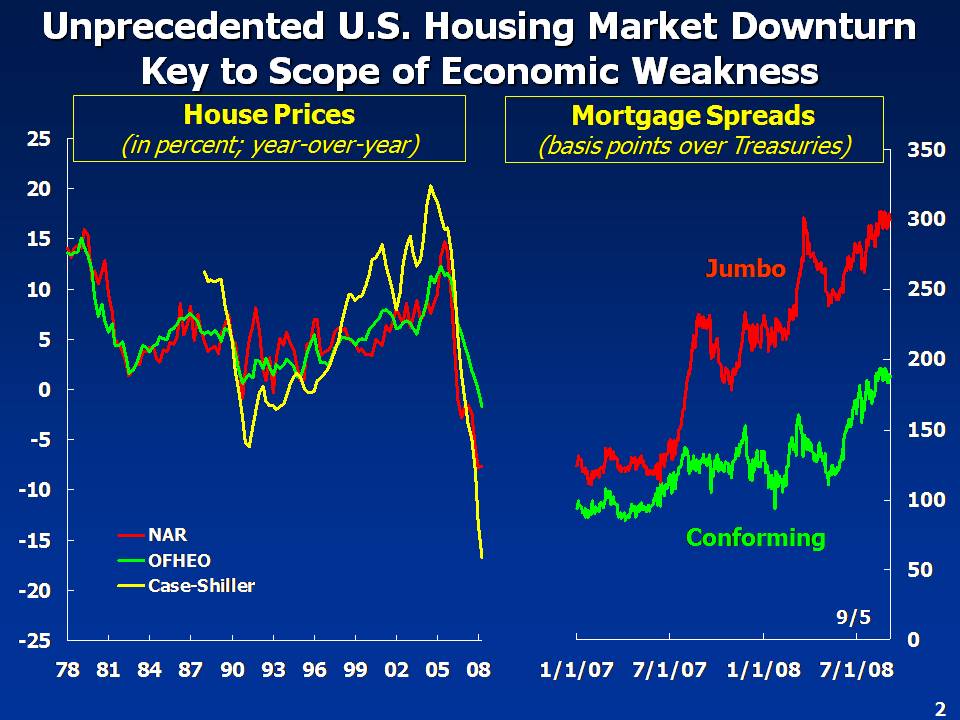

Housing and credit markets remain at the core of the U.S. slowdown. House prices, on a national basis, continue to decline and inventories of unsold homes remain high, and the sizeable drag on growth from residential investment is likely to continue albeit at a diminishing rate. In credit markets, relatively high mortgage rates and tighter lending standards still weigh on housing demand. At the same time, consumption—a key support of the U.S. economy until recently—is facing strong headwinds, such as tighter credit, falling asset prices for both residential real estate and corporate equity, as well as weaker labor markets and sluggish growth of disposable incomes. Under our baseline, U.S. growth on a fourth-quarter-on-fourth-quarter basis would slow to about 1 percent in 2008 and then recover gradually to about 1½ percent in 2009.

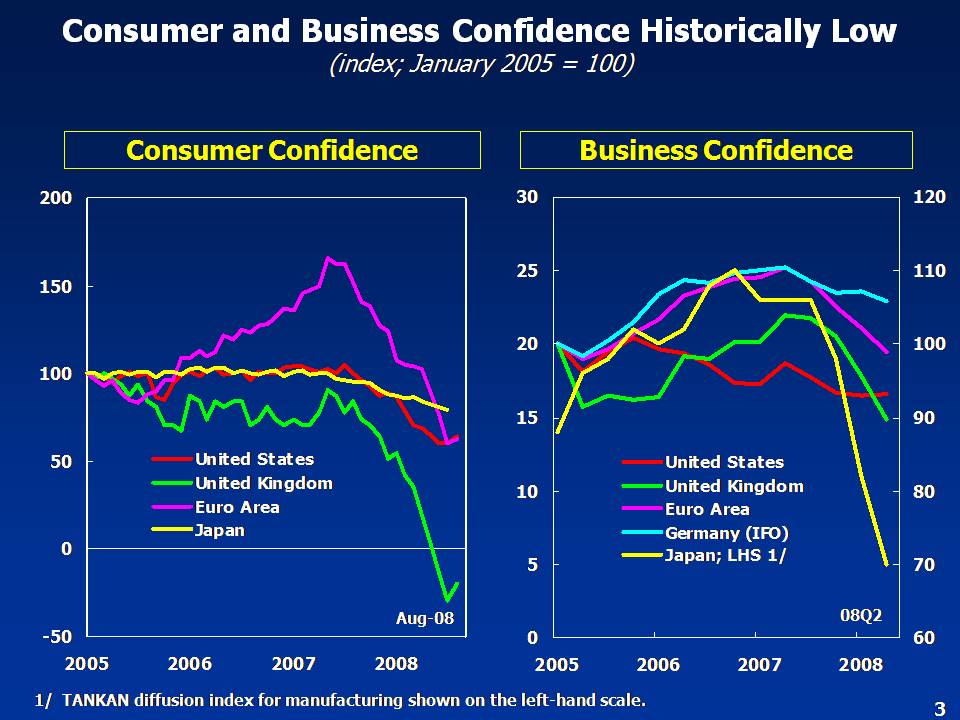

In Western Europe, growth is slowing amid weak business and consumer sentiment and softer industrial activity, reflecting terms of trade losses, weaker partner country growth, the impact of strong currencies on trade, and tighter credit conditions. High oil and food prices have cut into real disposable incomes, while financial strains and declining housing markets are increasingly a drag on domestic demand in several countries—including Spain, the United Kingdom, and Ireland. We project growth for the euro area on a fourth-quarter-on fourth-quarter basis at about ¾ percent in 2008 and about 1½ percent in 2009.

In contrast, notwithstanding some moderation, economic momentum has remained robust in emerging economies. Growth has moderated from more than 8 percent to just over 7 percent over the past year, largely reflecting slower export growth as a result of weaker demand from advanced economies. Nonetheless, growth in the largest emerging economies—Brazil, China, India, and Russia—continues to contribute about 40 percent to global GDP growth. While not at the center of the slowdown, emerging economies—where domestic demand has held up remarkably well—are being affected too, through both trade and financial channels.

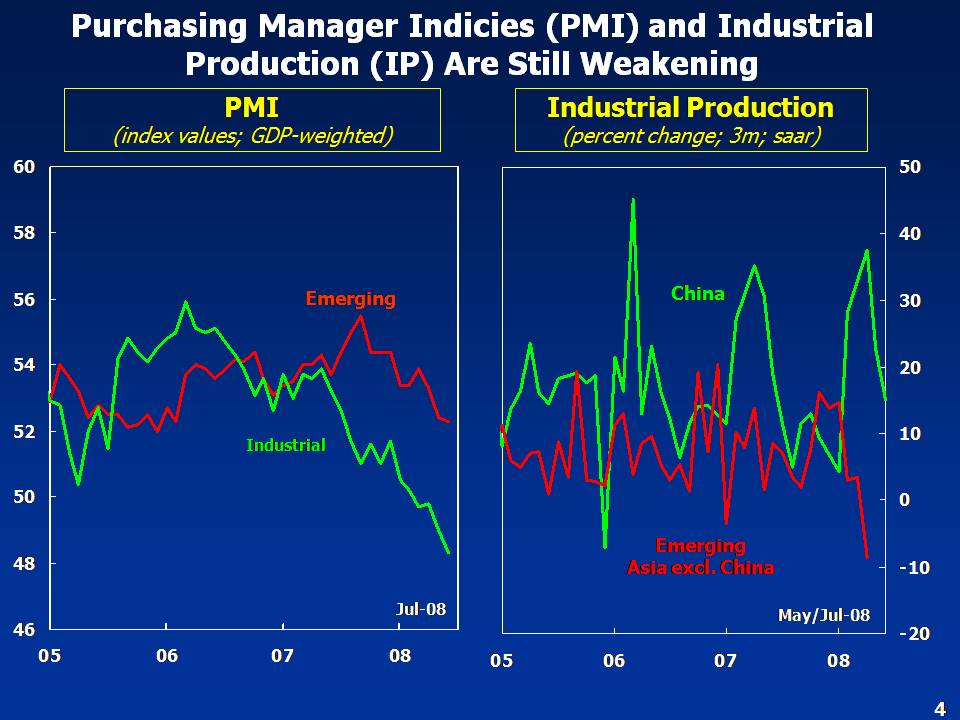

Going forward, growth momentum is likely to lose some steam in emerging economies, but the degree of deceleration would differ across regions. Signs of deceleration are most pronounced for several Emerging Asian economies that are tightly linked to the global manufacturing cycle, including the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan PoC, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and—to a lesser extent—India. Headwinds to activity have also intensified for Emerging Europe and Latin America, owing to these regions' exposure to the euro area and the United States through trade and financial channels. Overall on a fourth-quarter-on-fourth-quarter basis, growth in emerging and developing economies is projected to ease from over 8 percent in 2007 to just over 6 percent in 2008, before reaccelerating to more than 7 percent in 2009.

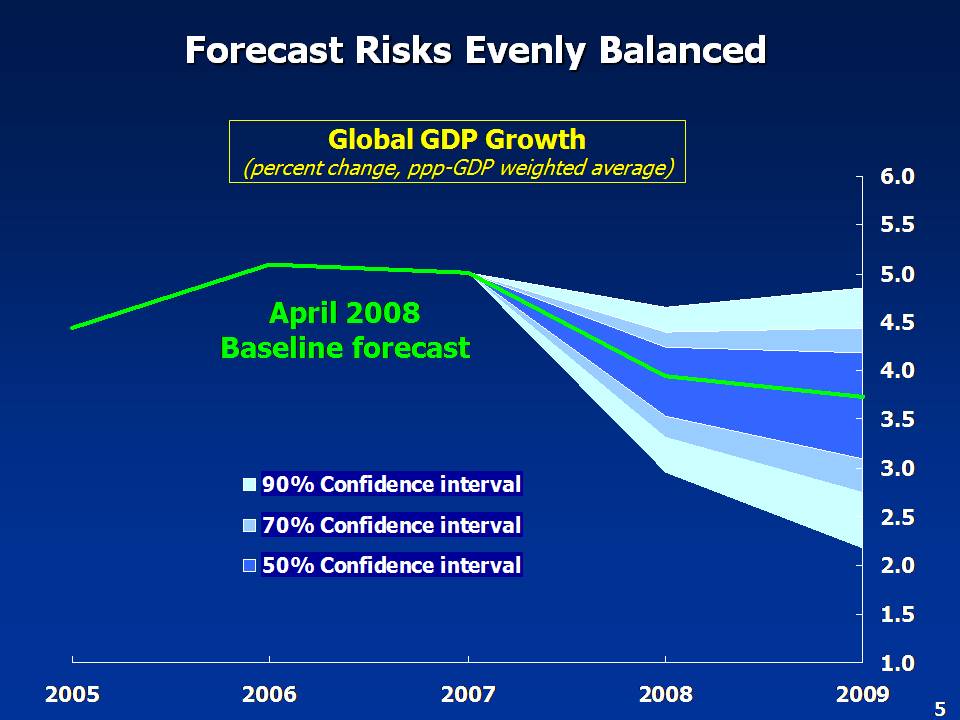

The global economy is projected to slow further in the second half of 2008, with a recovery gaining pace gradually in 2009. Global GDP growth would slow from 5 percent in 2007 to about 3 percent late in 2008 and reaccelerate toward 4 percent in the course of 2009. The specific figures are still under review and will be released in our World Economic Outlook next month. The recovery of global economic activity in 2009 would be driven by the unwinding of the effects of the more than 50 percent increase in oil prices in 2008 and the bottoming out of the U.S. housing sector. This would be supported by continued robust domestic demand in many emerging economies, which have benefited from rapid integration with the global economy and have been affected to a much smaller extent by the financial turmoil.

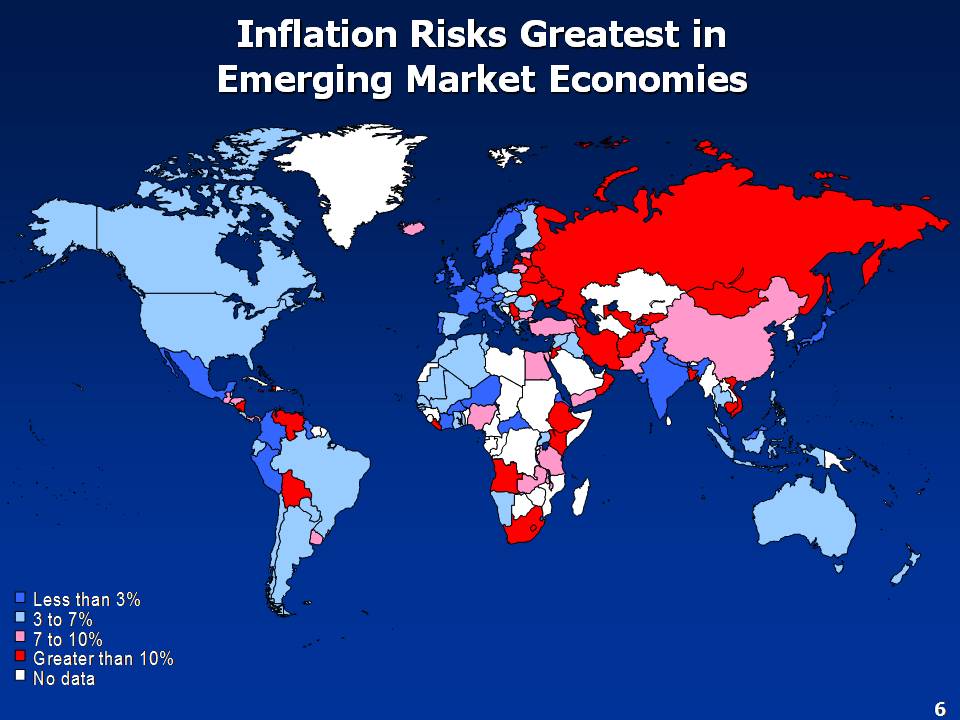

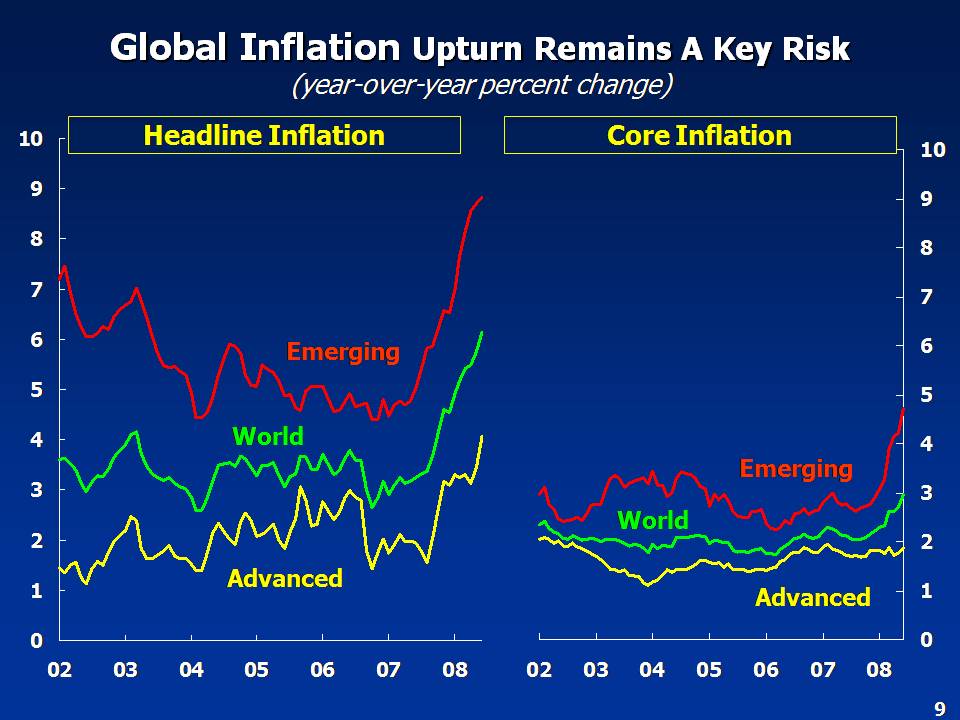

Notwithstanding slowing activity, headline inflation around the world has risen to its highest rate since the late 1990s, propelled by the surge in key commodity prices. In the advanced economies, headline inflation rose to around 4½ percent in July, underpinned by the rise in oil prices. The resurgence in inflation has gone much further in the emerging and developing countries where it rose to 9 percent in the aggregate in July, led largely by food price increases, with a wide swathe of countries experiencing double-digit inflation [shown in red in the map]. The recent declines in commodities prices may provide some respite, but nevertheless some increases still remain in the pipeline, since changes in international prices feed into local prices only with a lag.

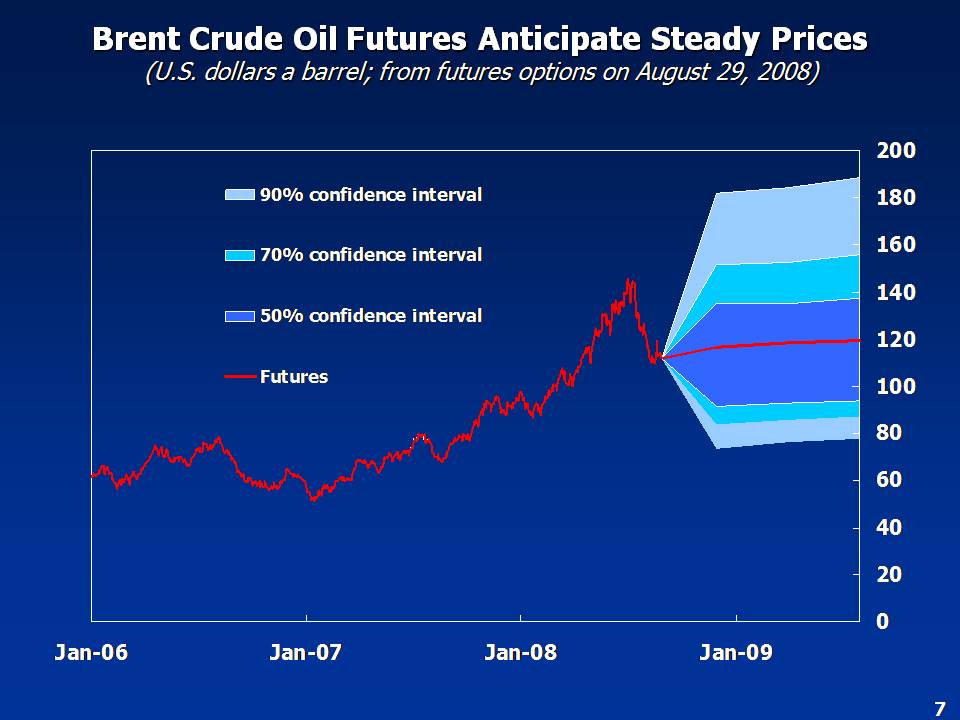

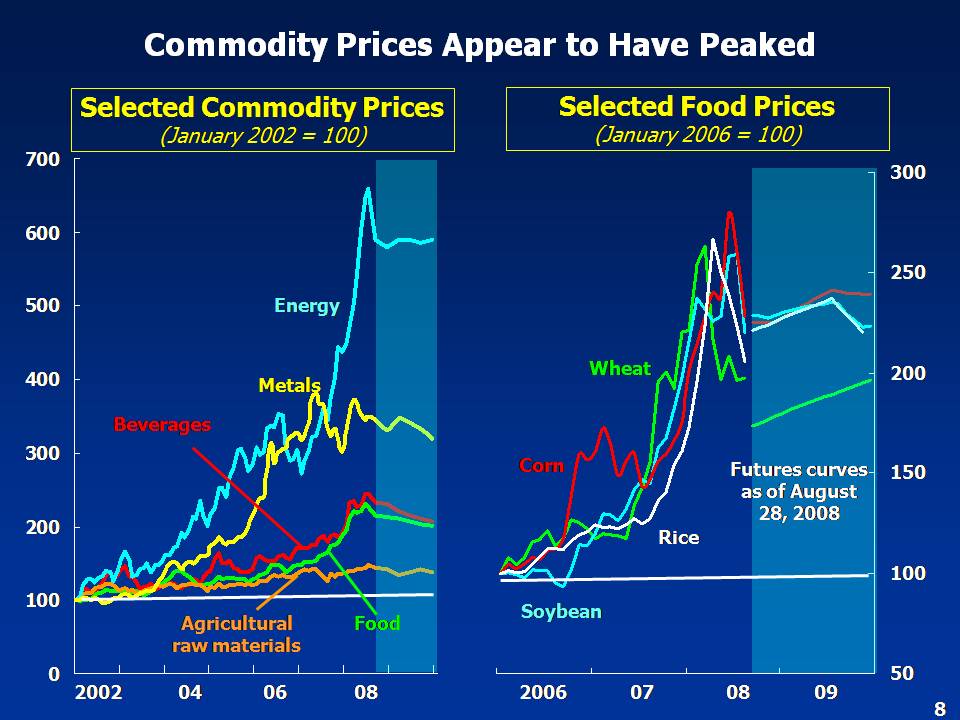

Oil prices have moderated recently, but they are still about 15 percent higher, on average, than at the beginning of 2008. In our view, high oil prices have largely reflected fundamental factors. Sustained strong demand growth—fueled by the acceleration of resource—intensive growth in emerging economies—a sluggish supply response, and declining inventories all contributed to the surge in prices. With weaker global growth and some demand response to higher oil prices, tight market balances between supply and demand in oil markets have eased some, allowing oil prices to recede from their peak.

Similarly, prices of major food commodities rose by almost 70 percent in the year to June 2008, but have moderated more recently. Looking ahead, we see commodity prices likely to stay at much higher levels than previously in real terms and highly sensitive to views about demand and supply trends. As for "speculation", we have found little hard evidence thus far that this has been a driving factor, although it is quite possible that investor behavior can amplify short-term price fluctuations, and we will continue to examine the issue.

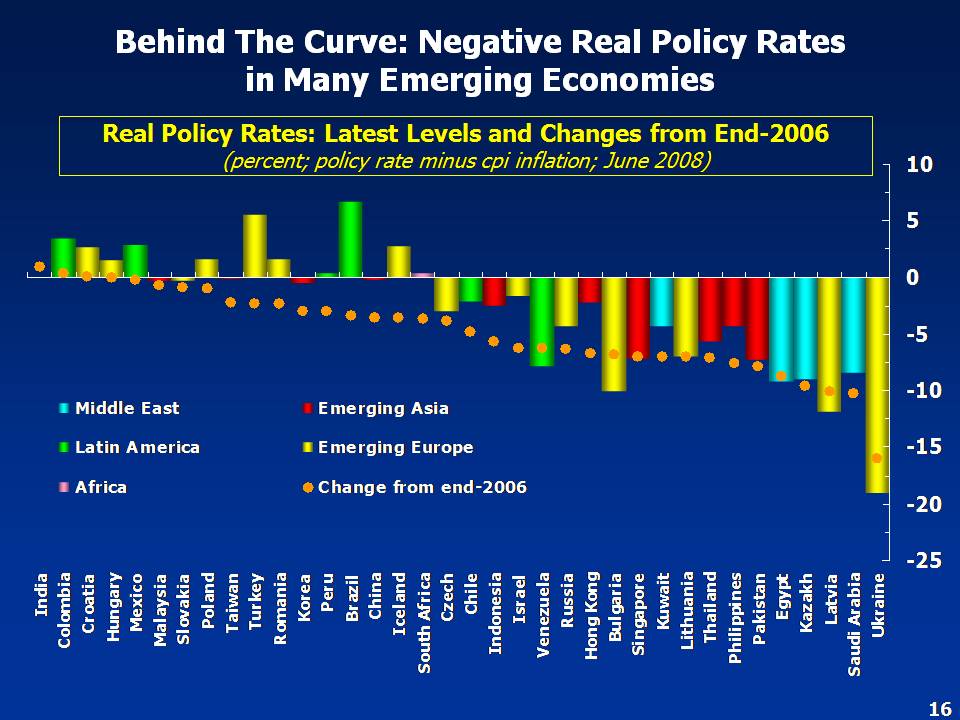

Core inflation in advanced economies has remained broadly contained, but has increased markedly in emerging economies. While the recent moderation of international commodity prices may ease some of the pressure, inflation risks in emerging economies remain serious since they are more vulnerable to second-round effects because of the greater weight of food in the consumption basket—typically in the range of 30-45 percent as opposed to 10-15 percent in the advanced economies—because inflation expectations are less well anchored by central bank credibility, and because fast growth has eroded margins of spare capacity.

Global Financial Strains

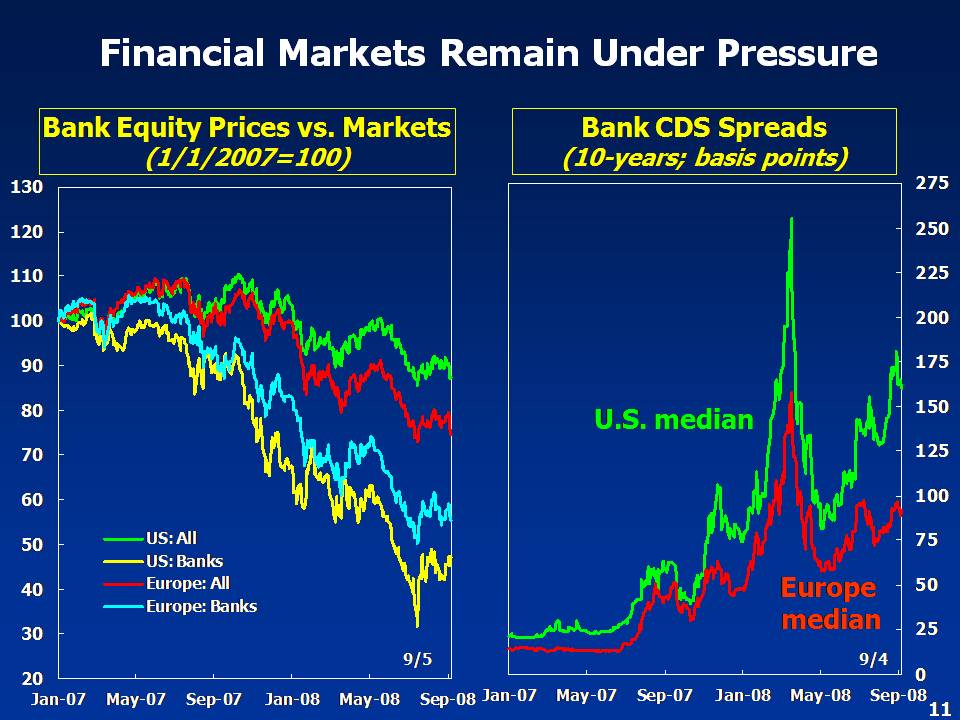

Let me now turn to financial markets in more detail. Risks in financial markets remain elevated and strains remain significant more than a year after signs of liquidity pressures first surfaced. Against this background, continued deleveraging in the financial sector is likely to act as a substantial constraint on the strength of the global economic recovery.

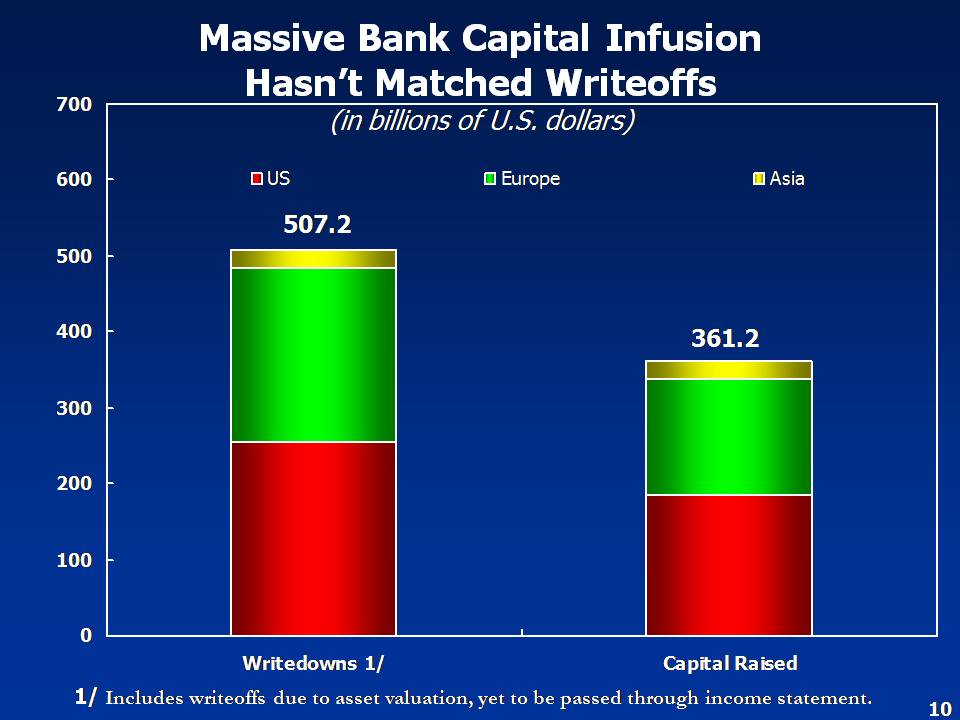

Balance sheet adjustment in the financial sector has been progressing. In both the United States and in Europe, banks have raised substantial amounts of capital while writing down about US$500 billion (largely on U.S. based assets), compared to our loss estimates of between US$560-685 billion for banks and about US$1.1 trillion for the entire global financial system.

However, the environment for raising capital and adjusting balance sheets is becoming much more challenging. With the downturn in economic activity, falling share prices, and rising funding costs, banks are facing stronger headwinds to adjust, while revenues are dropping from activities like securitization and leveraged buyouts.

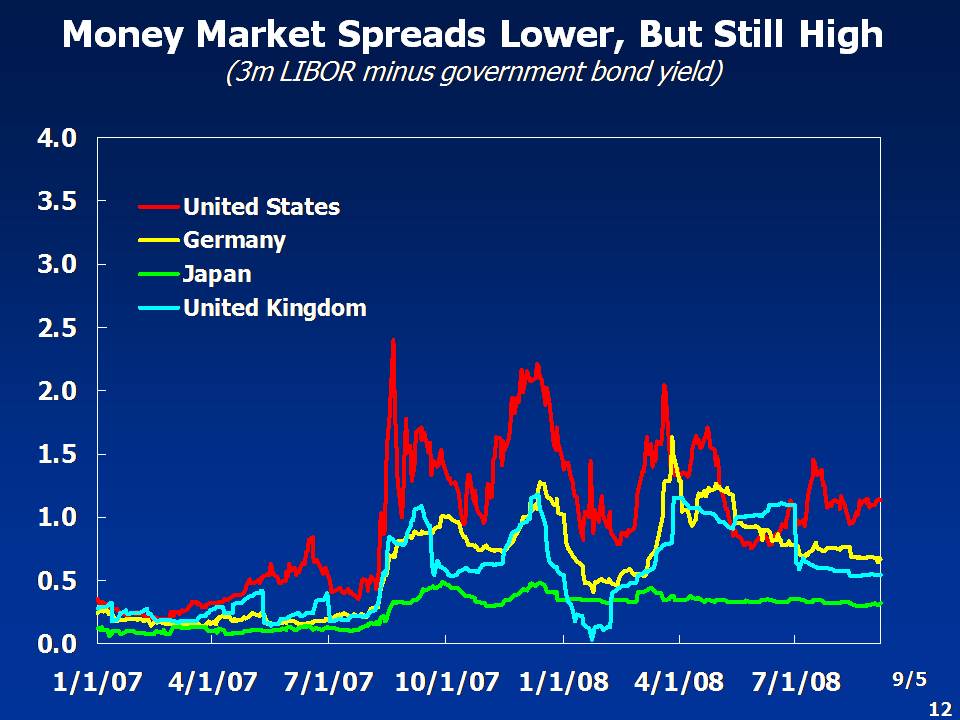

Also, liquidity risks remain elevated. Conditions in short-term funding markets remain strained—notwithstanding the exceptional actions taken by major central banks, and some markets remain illiquid—complicating price discovery. Uncertainty about who holds what types of assets and how they are valued, in turn, has helped fuel difficulties in interbank markets. Specifically, analysis in our upcoming GFSR indicates that strains in funding markets reflect not only liquidity but credit risks and counterparty concerns (notably, risks attached to joint probabilities of default)—factors which have likely kept major central banks on the defensive and have not allowed them to get sufficiently ahead of the problem.

At the same time, elevated credit risks reflect the ongoing pressures on bank balance sheets, as well as signs of wider credit deterioration (under slower economic growth), particularly in areas exposed to the U.S. mortgage, construction, and commercial real estate markets.

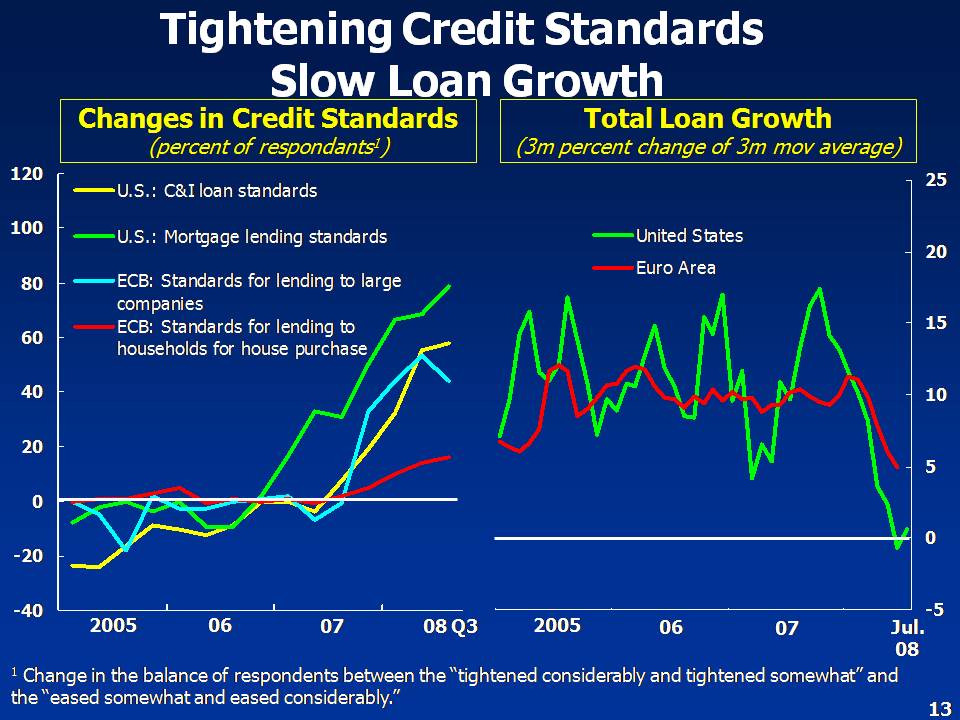

Correspondingly, monetary and financial conditions have further tightened. Alongside reduced risk appetite, falling share prices and rising spreads on mortgage and corporate debt have offset effects of monetary easing on financing costs. And bank lending standards continue to tighten (or remain tight) across advanced economies, as part of a worrisome feedback loop between slower growth and the reduced willingness of financial institutions to extend credit.

A major risk going forward is one of significant financial deleveraging, weighing on global growth prospects for a prolonged period.

• In terms of macroeconomic and financial interactions, if firms cannot raise capital, inevitably they will need to limit the size and riskiness of their assets, which could restrain the flow of credit and dampen growth. At the same time, weaker growth increases pressure on financial firms' balance sheets, including through weaker collateral and profitability.

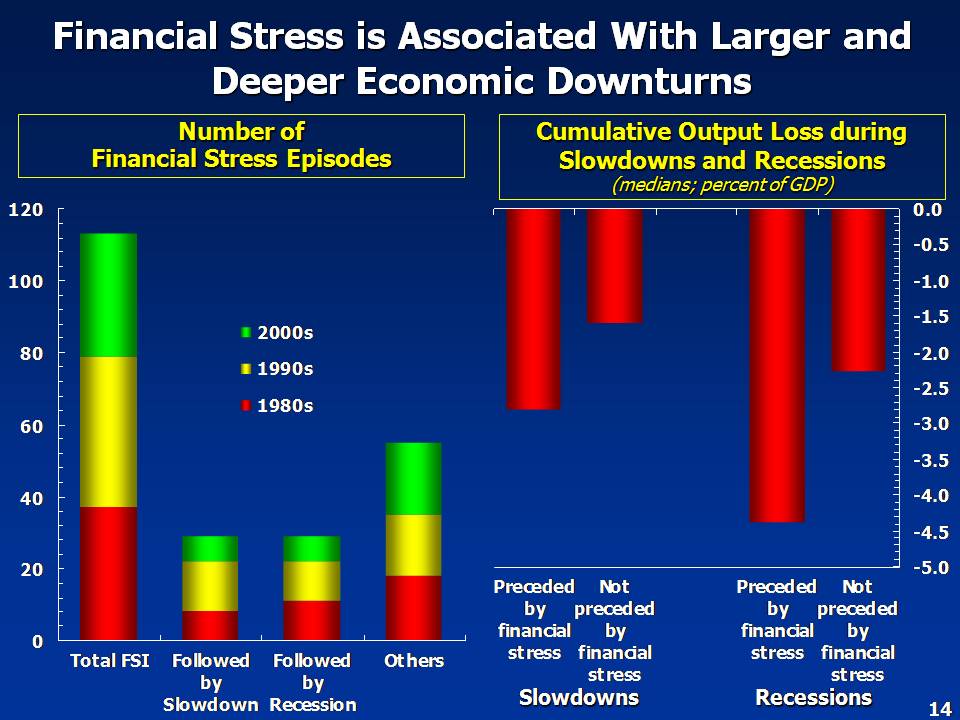

• New analysis that will appear in the upcoming World Economic Outlook also suggests that financial strains characterized by significant stress in the banking sector are more likely to be associated with severe economic downturns. Interestingly, countries with more "arms-length" financial intermediation fare no better in this regard than bank-based systems. The leverage of banks in such economies tends to be relatively pro-cyclical, resulting from the interplay between banks' lending activities and valuations in securities markets.

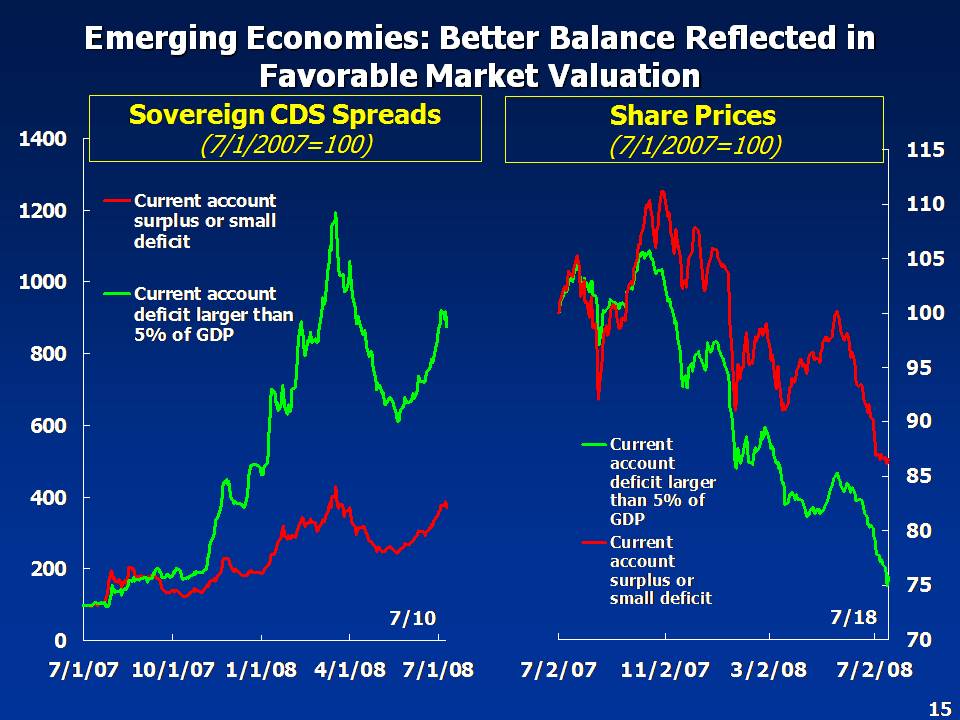

Emerging economies have thus far been less affected by the financial crisis, but financial conditions have tightened as international investors have become more risk averse. Securities and bank flows to emerging economies have generally remained solid, but equity prices have declined and bond spreads have widened. That said, countries with larger external deficits have underperformed in both credit and equity markets. This is suggestive of greater vulnerability to spillovers from stress in advanced economies. Large deficits are concentrated in Emerging Europe and a number of other countries and regions (e.g., Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, Vietnam, and Central America).

Policies

Many would conclude from the picture that I have just portrayed—slowing global growth, protracted financial strains, and higher inflation—that I am quite pessimistic about the immediate future. But I am not. The reason is that, in my view, there are positive aspects of the current situation that point toward recovery. Moreover, sound policy options are on offer to effectively address many of the tough problems that we face, but policy makers will need to avail themselves of that opportunity and take the right steps.Macroeconomic policies need to support the recovery and ensure that the sustained shift in relative prices implied by high commodity prices does not ratchet up inflation, as it did in the 1970s.

• In advanced economies, we expect the slowdown in activity to help contain inflation going forward. Weakening domestic demand, increasing output gaps and sluggish labor markets should limit pressures on underlying inflation. Moreover, the recent sharp decline in oil prices should help alleviate short-term pressures on headline inflation. Thus, policymakers can afford to keep rates on hold in the face of elevated headline inflation, while watching closely for signs of easing price pressure that would permit a more accommodative stance in economies with relatively high real interest rates.

• Underlying inflationary pressures are building in many emerging and developing economies and policy rates remain low in real terms. Monetary policies may be "behind the curve" in some cases and banking on immediate relief from retreating oil prices is risky. Instead, policies in these instances need to be tightened, lest central banks run the risk that hard-won policy credibility could be eroded. In some cases, allowing greater exchange rate flexibility would provide room for operating a more independent monetary policy. But where this is not a short-term option, fiscal policy should shoulder the burden of adjusting the macroeconomic policy stance.

In financial markets, more broadly, the immediate task is to restore more effective market functioning.

• Financial authorities share with financial institutions themselves the responsibility for improving market discipline. This includes ensuring compliance with new guidelines on liquidity risk management (building on the Basel Committee's June 2008 proposals); enhancing financial disclosure of exposures to structured credit and mortgage-related assets; removing non-comparable accounting treatments across countries; and effective public oversight.

• More generally, authorities should continue to encourage financial institutions to strengthen their capital positions. Given the fragility of market conditions, we welcome recent actions by the U.S. authorities to support the housing GSEs. The intervention in the GSEs and the broader support to the mortgage market should stabilize the GSEs' balance sheets and the funding of mortgages in the near-term. This will help underpin the U.S. housing market, the banking system, and the broader economy.

• The authorities have appropriately addressed the moral hazard concerns over intervention by diluting common and preferred shares of stockholders, and replacing existing management. Over the longer term, the restructuring of the GSEs remains essential to restore market discipline, minimize fiscal costs, and limit future systemic risks. The GSEs are in no-man's-land between public and private ownership and this needs to be resolved.

Finally, one of the important lessons I take away from the global financial turmoil of the past year has been the key role of collaborative action and more will be needed in the future. We saw this early on in the actions taken by the major central banks to relieve stress in short-term funding markets—joint actions that were entirely appropriate. The financial turmoil has revealed that national financial stability frameworks have failed to keep up with financial market innovation and globalization, at the price of deleterious cross-border spillovers. Greater cross-border coordination and collaboration among national prudential authorities is needed, particularly for the purpose of detecting, managing, and resolving financial stress. International bodies such as the Financial Stability Forum, BIS, and the IMF are playing a crucial role in alleviating the tensions between national accountability on the one hand and international spillovers of national actions on the other. Nonetheless, more political will to drive forward coordination and collaboration is essential. This is particularly important within the European Union, given member countries' quest to build a single market for financial services.

Thank you.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |