The global economy continues to recover from the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the cost-of-living crisis. In retrospect, the resilience has been remarkable. Despite war-disrupted energy and food markets and unprecedented monetary tightening to combat decades-high inflation, economic activity has slowed but not stalled. Even so, growth remains slow and uneven, with widening divergences.

The global economy is limping along, not sprinting.

According to our latest projections, world economic growth will slow from 3.5 percent in 2022 to 3 percent this year and 2.9 percent next year, a 0.1 percentage point downgrade for 2024 from July. This remains well below the historical average.

Headline inflation continues to decelerate, from 9.2 percent in 2022 on a year-over-year basis, to 5.9 percent this year and 4.8 percent in 2024. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, is also projected to decline, albeit more gradually, to 4.5 percent next year. Most countries aren’t likely to return inflation to target until 2025.

As a result, projections are increasingly consistent with a soft landing scenario, bringing inflation down without a major downturn in activity, especially in the United States, where our forecast increase in unemployment is now modest, from 3.6 percent to 3.9 percent by 2025.

But important divergences are appearing, leaving activity in some regions much below pre-pandemic projections. The slowdown is more pronounced in advanced economies than in their emerging market and developing counterparts. Among advanced economies, the US growth outlook has been revised up, with resilient consumption and investment, while euro area activity was revised downward. Many emerging market economies also proved unexpectedly resilient, with the notable exception of China, which faces growing headwinds from its real estate crisis and weakening confidence.

Three forces are at play:

- The recovery in services is almost complete and the strong demand that supported services-oriented economies is now softening.

- Tighter credit conditions are weighing on housing markets, investment, and activity, more so in countries with a higher share of adjustable-rate mortgages or where households are less willing, or able, to dip into their savings. Firm bankruptcies are increasing in some economies, although from historically low levels. Countries are now at different points in their hiking cycle: advanced economies (except Japan) are near the peak, while some emerging market economies that started hiking earlier, such as Brazil and Chile, have already started easing.

- Inflation and economic activity are shaped by last year’s commodity price shock. Economies heavily dependent on Russian energy imports saw a steeper increase in energy prices and a sharper slowdown. The passthrough from higher energy prices played a large role in driving core inflation higher in the euro area—unlike the United States, where core inflation pressures instead reflect a tight labor market.

Despite signs of softening, labor markets in advanced economies remain buoyant with historically low unemployment rates helping to support activity. Real wages are catching up, but there is scant evidence of a wage-price spiral. Further, many countries experienced a sharp—and welcome—compression in the earnings distribution, with the higher amenity value of flexible and remote work schedules reducing wage pressures for high earners.

Gauging risks

While some of the extreme risks—such as severe banking instability—have moderated since April, the balance remains tilted to the downside.

China’s real-estate crisis could intensify, posing a complex policy challenge. Restoring confidence requires promptly restructuring struggling property developers, preserving financial stability, and addressing the strains in local public finance.

If China’s real estate prices decline too rapidly, the balance sheets of banks and households will worsen, with the potential for serious financial amplification. Artificially supporting real estate prices may temporarily protect balance sheets, but this will crowd out other investment opportunities, reduce new construction, and hurt local government revenues through reduced land sales. Either way, China’s economy must pivot away from growth that relies on credit for the real estate sector.

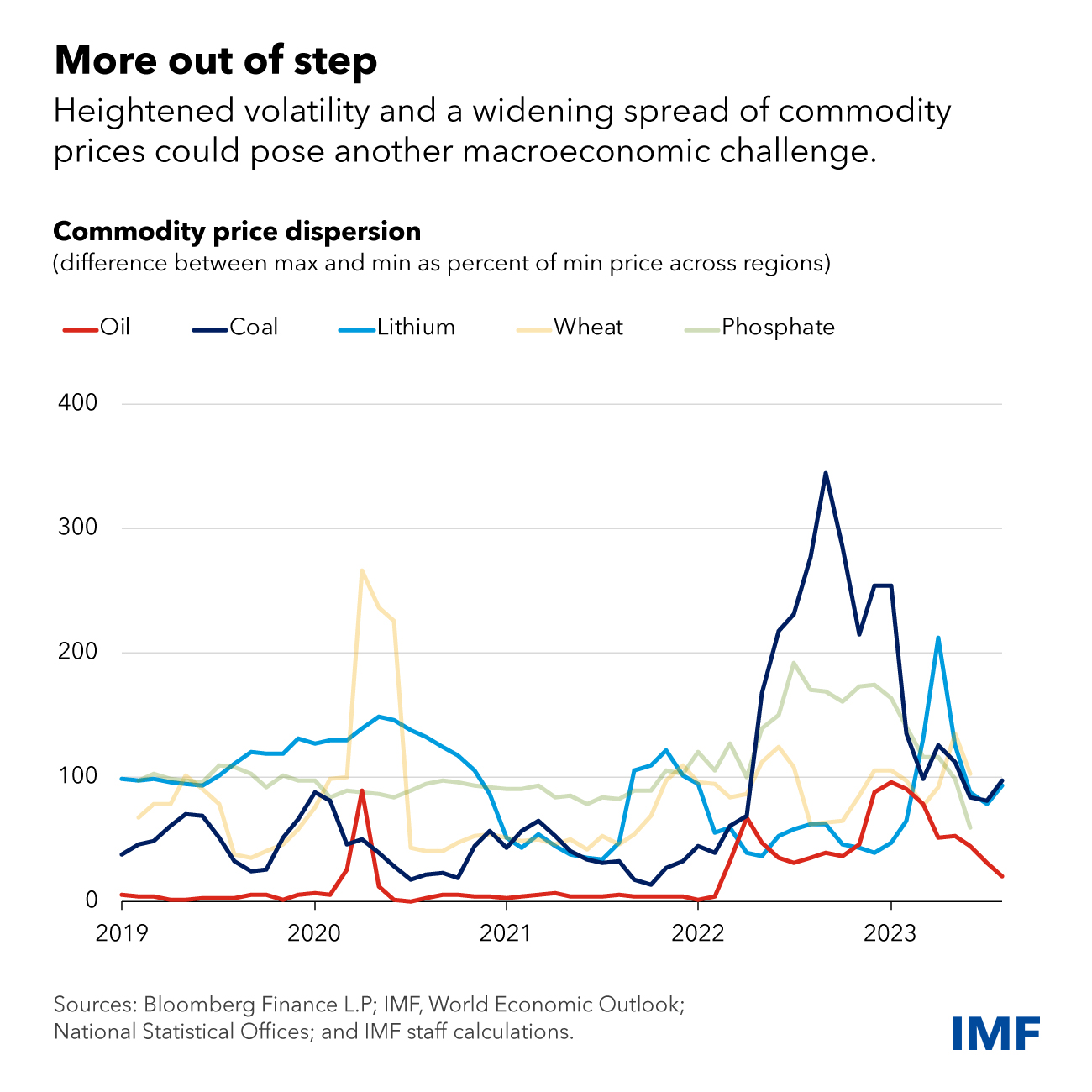

Meanwhile, commodity prices could become more volatile amid climate and geopolitical shocks, a serious risk to disinflation. Between June and late September, oil prices had increased by about 25 percent amid extended supply cuts by OPEC Plus, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and selected nonmembers, before falling back by about 11 percent. Food prices remain elevated and could be further disrupted by an escalation of the war in Ukraine, inflicting greater hardship on many low-income countries. Geoeconomic fragmentation has also led to a sharp increase in the dispersion in commodity prices across regions, including critical minerals. This could pose serious macroeconomic risks, including to the climate transition, as we show in Chapter 3 of our latest World Economic Outlook.

And, while both underlying and headline inflation have decreased, they remain uncomfortably high. Near-term inflation expectations have risen markedly above target, although they now appear to be turning a corner. As Chapter 2 of the WEO details, bringing these near-term inflation expectations back down is critical to winning the battle against inflation.

In addition, fiscal buffers have eroded in many countries, with elevated debt levels, rising funding costs, slowing growth, and an increasing mismatch between the growing demands on the state and available fiscal resources. This leaves many countries more vulnerable to crises and demands a renewed focus on managing fiscal risks.

Finally, despite tightening monetary policy, financial conditions have eased in many countries, as detailed in the latest Global Financial Stability Report. The danger is of a sharp repricing of risk, especially for emerging markets, that would further strengthen the US dollar, trigger capital outflows, and increase borrowing costs and debt distress.

Policy priorities

Under our baseline scenario, inflation continues to recede as central banks maintain a tight stance and avoid easing prematurely. Once the disinflation process is firmly established, with decreasing near-term inflation expectations and inflation targets coming into sight, gradually cutting the policy rate will be appropriate, while maintaining a commitment to price stability.

Fiscal policy needs to rebuild buffers, including by removing energy subsidies, while still protecting the vulnerable. This will also aid disinflation. Fiscal and monetary policies pulled in the same direction last year as many pandemic emergency fiscal measures were unwound, but they are less aligned this year. The substantial widening of the fiscal deficit in the United States is most worrying, as fiscal policy should not be pro-cyclical, especially at this stage of the inflation cycle.

We should also return our focus to the dimming medium-term outlook. Global growth prospects are weak, especially for emerging market and developing economies. The implications are profound: a much slower convergence toward the living standards of advanced economies, reduced fiscal space, increased debt vulnerabilities and exposure to shocks, and diminished opportunities to overcome the scarring from the pandemic and the war.

With lower growth, higher interest rates and reduced fiscal space, structural reforms become key. Higher long-term growth can be achieved with a careful sequencing of reforms, starting with those focused on governance, business regulation and the external sector. These first-generation reforms help unlock growth and make subsequent reforms—whether to credit markets, or for the green transition—much more effective.

Multilateral cooperation can help ensure countries achieve better growth outcomes. Countries should avoid implementing policies that contravene World Trade Organization rules and distort international commerce. And countries should safeguard the flow of critical minerals, needed for the climate transition, and of agricultural commodities. Such “green corridors” would help reduce volatility and accelerate the green transition.

Finally, all countries should prevent geoeconomic fragmentation that impedes progress toward a shared prosperity. Instead, they should work to restore trust in rules-based multilateral frameworks that enhance transparency and policy certainty. A robust global financial safety net with a well-resourced IMF at its center is essential.