Banking oversight was significantly strengthened after the global financial crisis, in part by requirements for banks to hold more capital and liquid assets and be stress tested to help ensure resilience to adverse shocks.

Yet the global financial system is showing considerable strains as rising interest rates shake trust in some institutions. The failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in the United States—caused by the fleeing of uninsured depositors out of the realization that high interest rates have led to large losses in these banks’ securities portfolios—and the government supported acquisition of Switzerland’s Credit Suisse by rival UBS have rocked market confidence and triggered significant emergency responses by authorities.

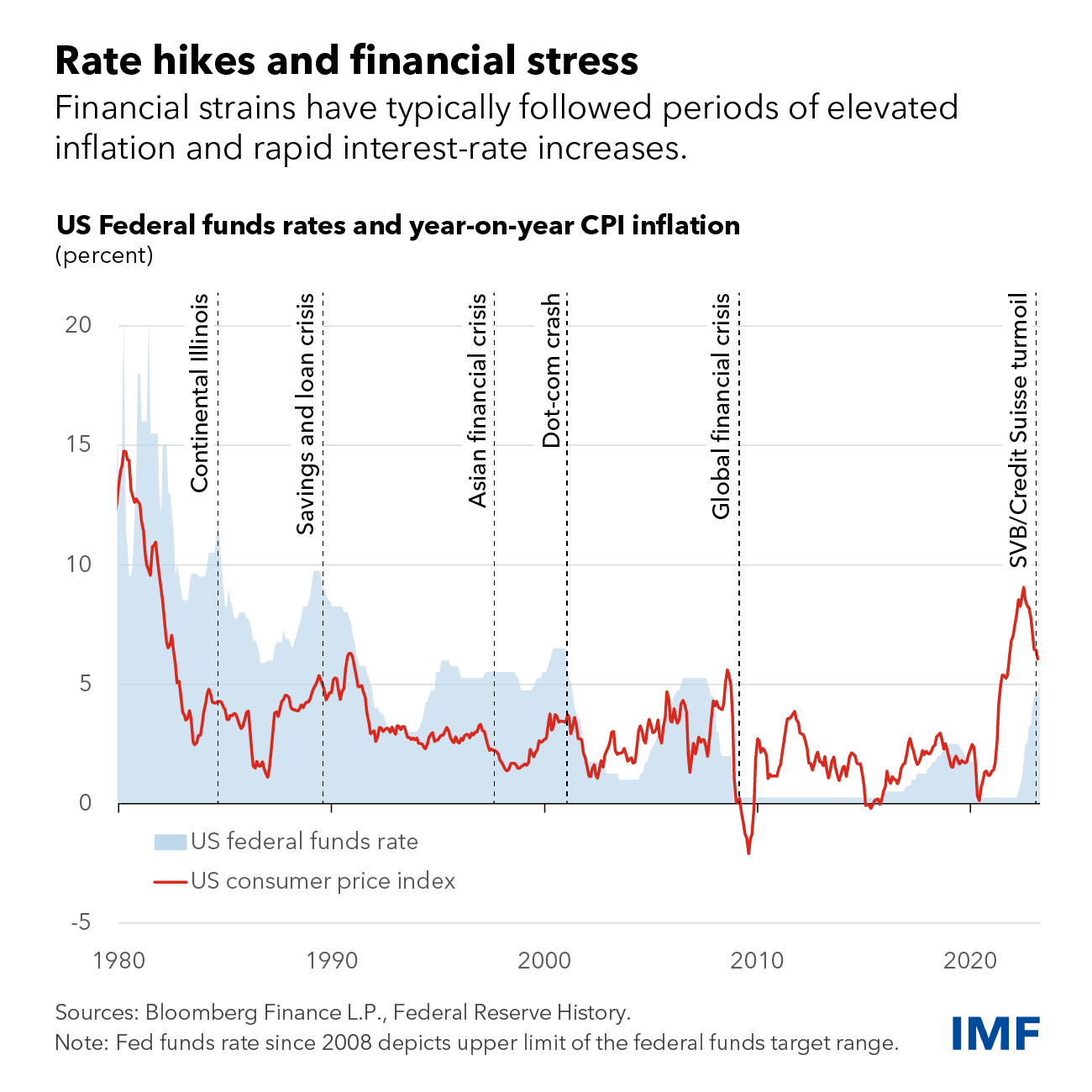

Our latest

Global Financial Stability Report shows that risks to bank and nonbank financial intermediaries have

increased as interest rates have been rapidly raised to contain inflation.

Historically, such forceful rate increases by central banks are often

followed by stresses that expose fault lines in the financial system.

In its role of assessing global financial stability, the IMF has flagged gaps in the supervision, regulation, and resolution of financial institutions. Previous Global Financial Stability Reports warned of strains in bank and nonbank financial intermediaries in the face of higher interest rates.

It’s not 2008

While the banking turmoil has raised financial stability risks, its roots are fundamentally different from those of the global financial crisis. Before 2008, most banks were woefully undercapitalized by today’s standards, held far fewer liquid assets, and had much more exposure to credit risk. In addition, there was excessive maturity and credit risk transformation of the broader financial system, high degrees of complexity of financial instruments, and risky assets predominantly funded by short-term loans. Troubles that began at some banks quickly spread to nonbank financial firms and other entities through their interconnections.

The recent turmoil is different. The banking system has much more capital and funding to weather adverse shocks, off balance sheet entities have been unwound, and credit risks have been curbed by more stringent post-crisis regulations. Instead, it was a meeting between the steep and rapid rise in interest rates and fast-growing financial institutions that were unprepared for the rise.

At the same time, we also learned that troubles at smaller institutions can shake broader financial market confidence, particularly as persistently high inflation continues to cause losses on banks’ assets. In this sense, the current turmoil is more akin to the 1980s savings and loan crisis and the events leading up to the 1984 failure of Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Co., which was then the largest in US history. These institutions were less capitalized and had unstable deposits.

Growing threats

Recently, bank stocks have declined on the industry’s travails, which have raised the cost of funding of banks and may well lead to curtailed lending. At the same time, perhaps surprisingly, overall financial conditions have not tightened meaningfully and remain looser than in October. Equity valuations remain stretched, notably in the United States. Modestly wider corporate credit spreads are largely offset by lower interest rates.

Investors are therefore pricing a fairly optimistic scenario and expect inflation to decline without much more increases in interest rates. While market participants see recession probabilities as high, they also expect the depth of the recession to be modest.

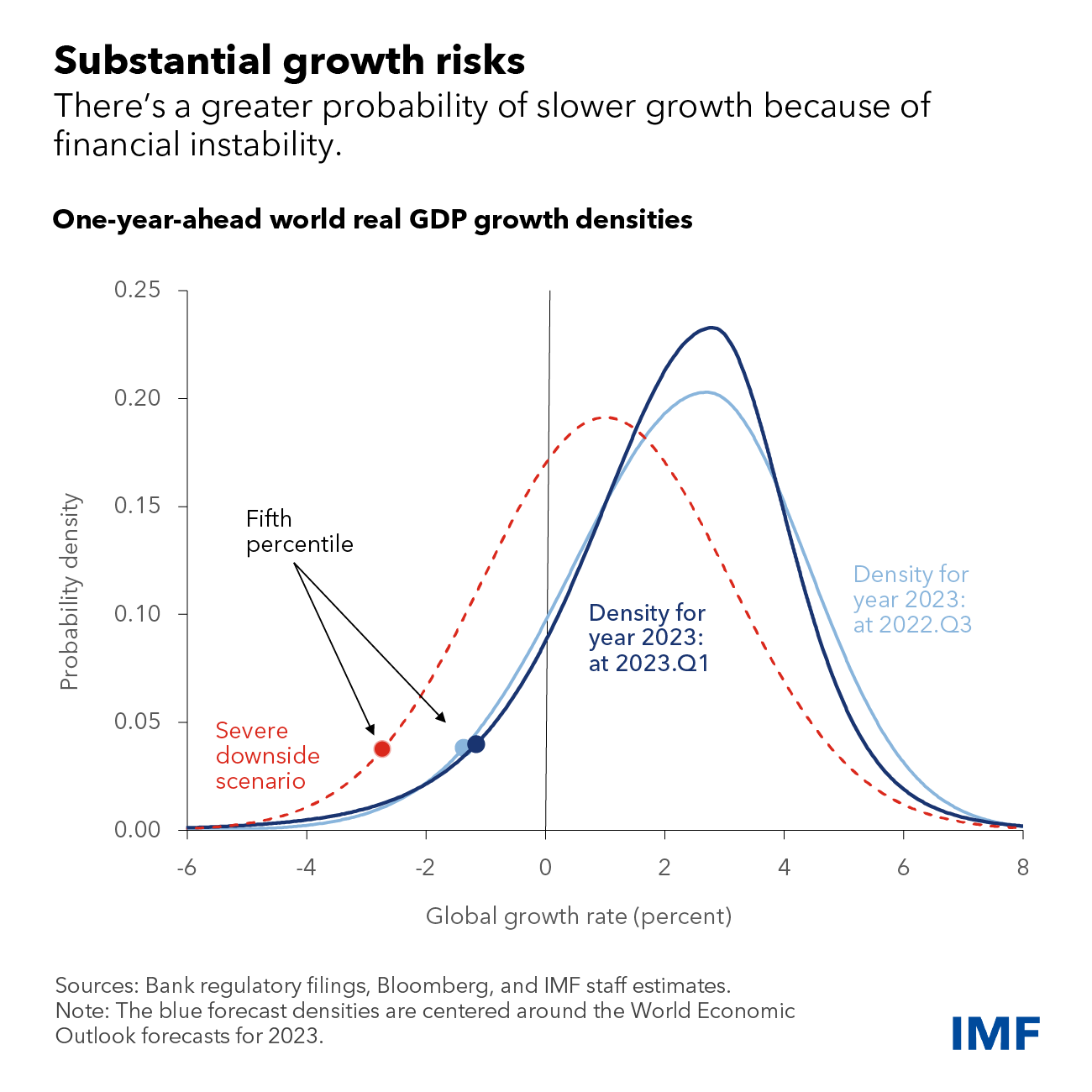

This sanguine view could be challenged by further acceleration of inflation, resulting in a reassessment by investors of the path of interest rates and possibly leading to an abrupt tightening in financial conditions. Stresses could then re-emerge in the financial system. Trust—the foundation of finance—could continue to erode. Funding could disappear rapidly for banks and nonbanks, and fears could spread, amplified by social media and private chat groups. Nonbank financial firms—a fast growing part of the financial system—could also be exposed to credit risk deterioration associated with a slowing economy. For example, some real estate funds have seen large declines in their asset valuations.

Shares of banks in major emerging market economies have so far experienced little contagion from the banking turmoil in the United States and Europe. Many of these lenders are less exposed to the risk of rising interest rates, but they generally hold assets with lower credit quality, and some have less deposit insurance coverage. Furthermore, high sovereign debt vulnerabilities are pressuring many lower-rated emerging market and frontier economies, with potential spillovers effects to their banking sectors.

Quantifying risks

Resolute policies

Faced with heightened risks to financial stability, policymakers must act resolutely to maintain trust.

Gaps in surveillance, supervision, and regulation should be addressed at once. Resolution regimes and deposit insurance programs should be strengthened in many countries. In acute crisis management situations, central banks may need to expand funding support to both bank and nonbank institutions.

These tools would help central banks maintain financial stability, allowing monetary policy to focus on achieving price stability.

If financial sector distress was to have severe repercussions affecting the broader economy, policymakers may need to adjust the stance of monetary policy to support financial stability. If so, they should clearly communicate their continued resolve to bring inflation back to target as soon as possible once financial stress lessens.

—This blog is based on Chapter 1 of the April 2023 Global Financial Stability Report, “A Financial System Tested by Higher Inflation and Interest Rates.”