Debt Restructuring in LICs

April 6, 2022

Faced with growing debt challenges, some low-income countries will likely have to restructure their debt. But debt restructurings in low-income countries will become more complex. In this Q+A, Guillaume Chabert, Martin Cerisola, and Dalia Hakura of the IMF’s Strategy, Policy and Review Department explain the challenges associated with debt restructurings in low-income countries and why timely, efficient, and orderly debt restructuring mechanisms are urgently needed.

How likely are low-income countries to need debt restructuring?

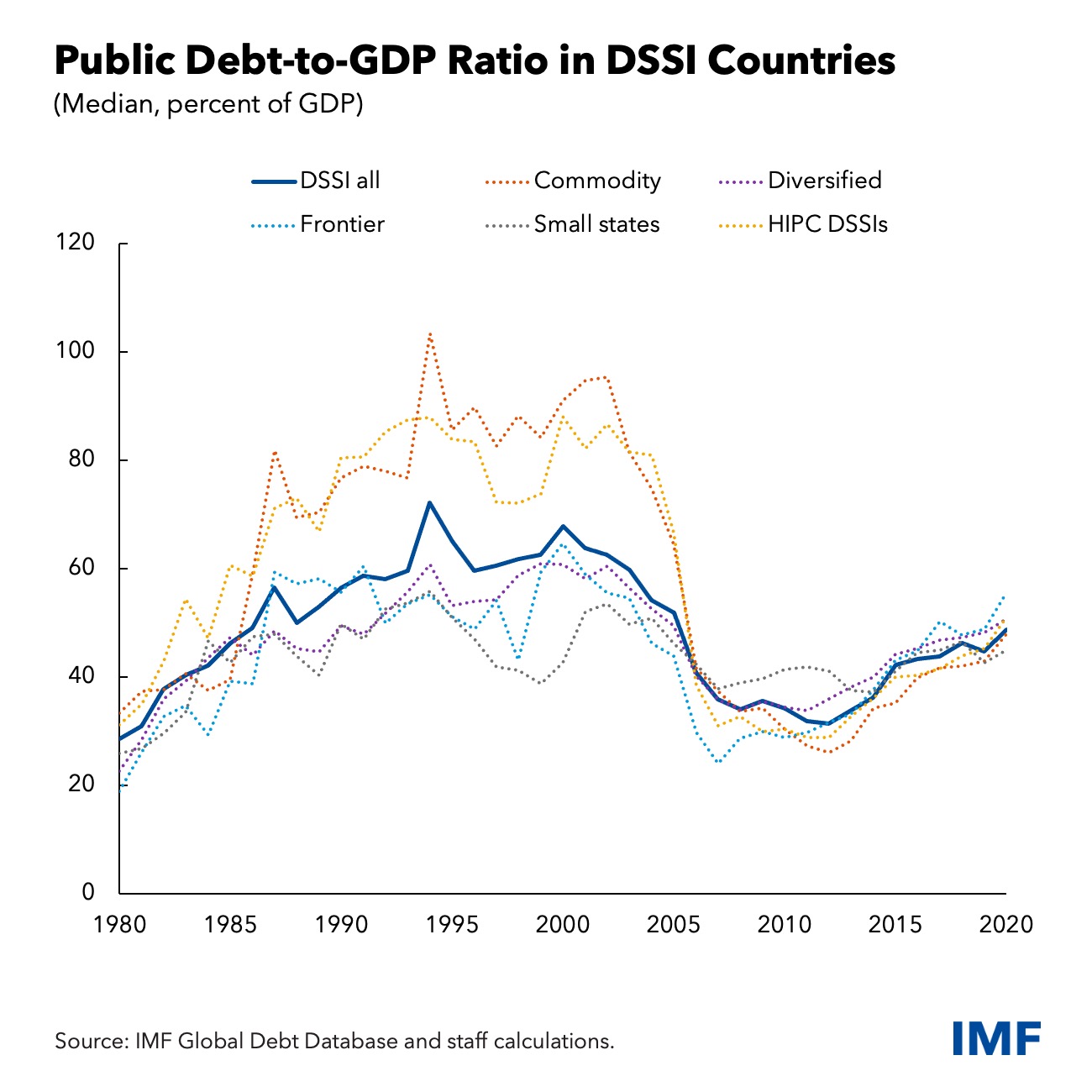

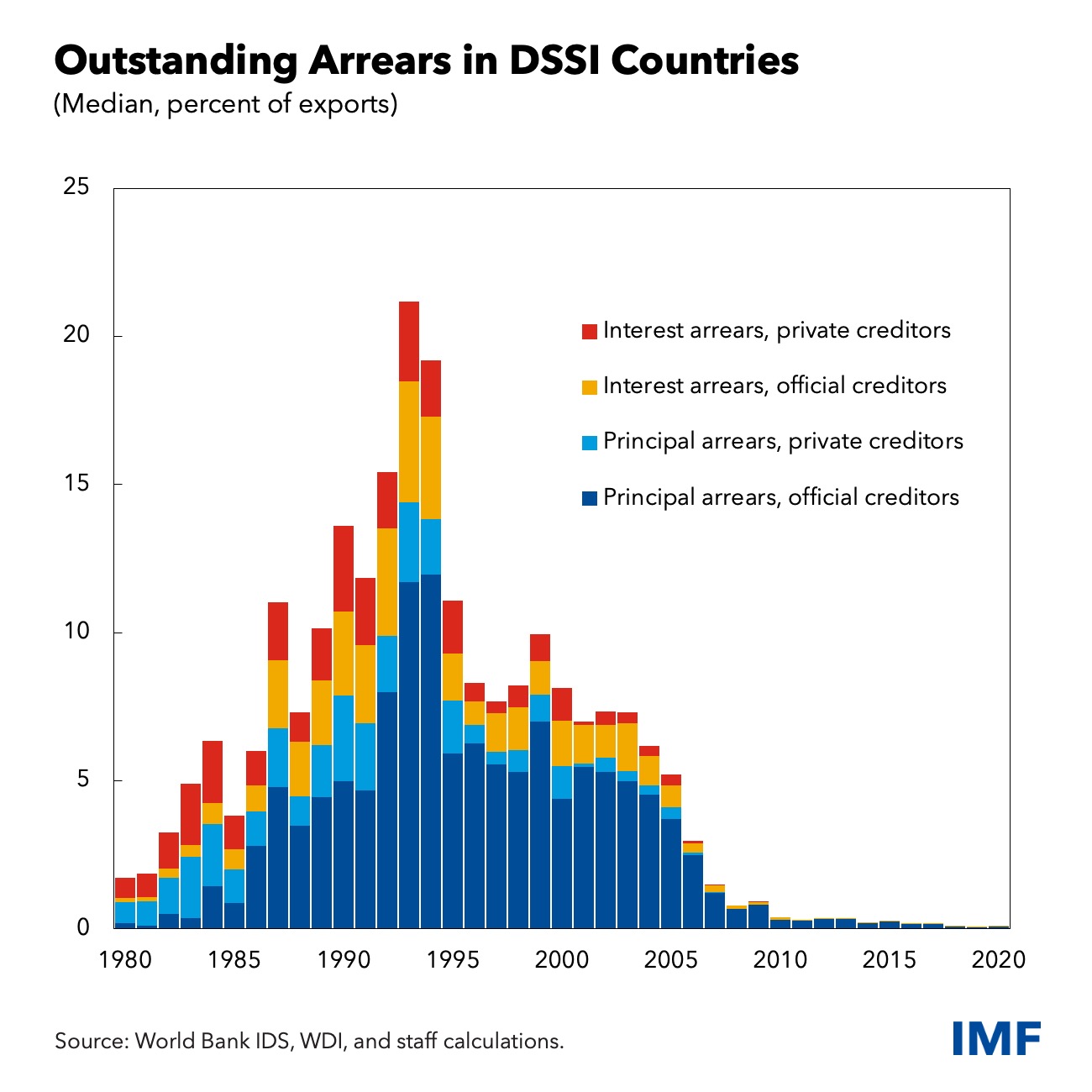

Debt challenges in low-income countries are far from where they were in the 1990s before the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, both in terms of debt levels (Chart 1) and accumulation of arrears (Chart 2). However, they have been on the rise for the last decade, in a context of low interest rates, high investment needs, limited progress in domestic revenue mobilization, and often constrained public financial management capacity. They have been further aggravated by the COVID-19 crisis and now by the fallout of the war in Ukraine.

Chart 1

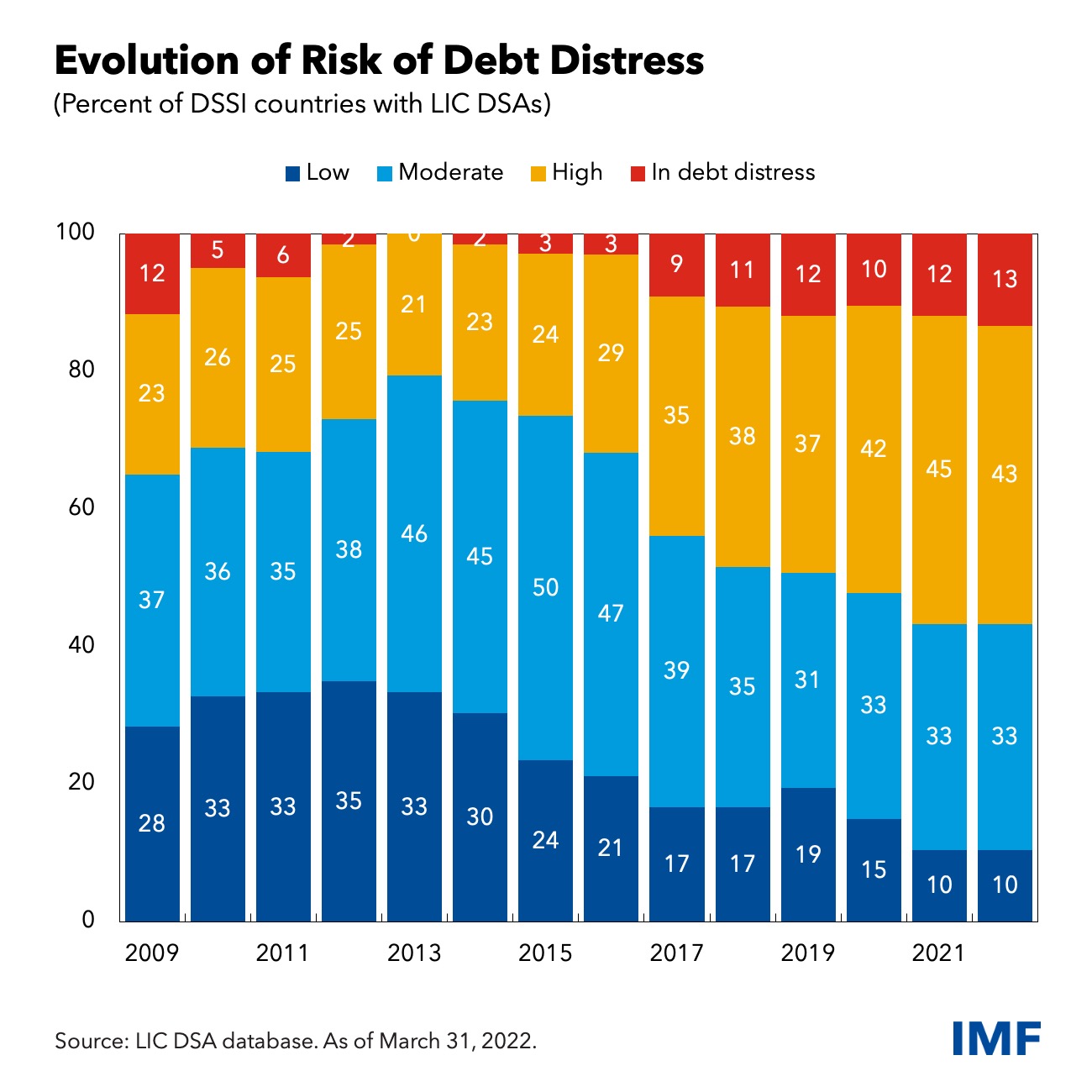

Let’s look at the situation faced by the 73 low-income countries that were eligible for the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in 2020–21 and are now eligible for the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments as detailed in a recent IMF note. About 60 percent of these countries are now at high risk or already in debt distress, compared to less than 30 percent in 2015 (Chart 3). Among the 41 DSSI countries at high risk or in debt distress, 4 have already undertaken a debt treatment and around 20 exhibit significant breaches of applicable high-risk threshold, half of which also have low levels of reserves and rising gross financing needs in 2022.

Chart 3

What will debt restructurings in DSSI countries involve?

Debt restructurings in DSSI countries will raise complex issues for both external and domestic debt.

On the domestic side, there will be difficult trade-offs between the need to restructure sovereign debt owed to domestic banks, in some cases, and the impact of those restructurings on financial stability and domestic banks ability to finance growth. Local currency debt for the median DSSI country rose from 7 percent of GDP in 2010 to 15 percent of GDP in 2021. For those DSSI countries with market access, local currency debt increased from 8 percent of GDP in 2010 to 28 percent of GDP in 2021. Many of these DSSI countries have also experienced a deepening of sovereign-bank links, with larger holdings of domestic sovereign debt at domestic banks.

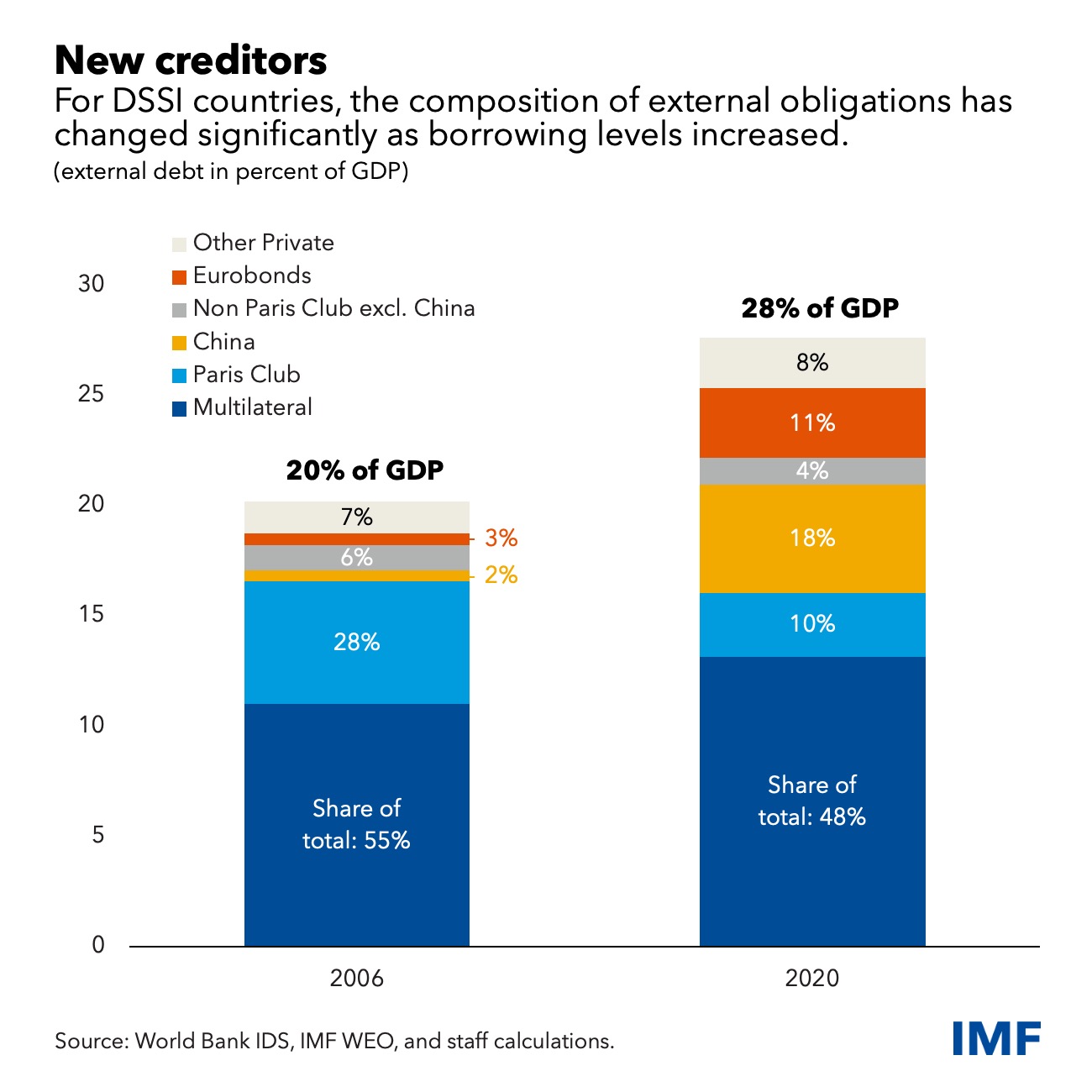

On the external side, increased diversity in creditor composition raises important coordination challenges. DSSI countries used to borrow mainly from Paris Club official bilateral creditors and private banks, alongside multilateral institutions. Paris Club creditors and private banks had strong coordination mechanisms, including through a shared understanding on how the two creditor groups interacted.

Today, external creditors are much more diverse, with a significant rise of China and private bondholders. This makes coordination significantly more challenging (Chart 4):

- In 2006, 28 percent of DSSI countries’ external debt was owed to Paris Club creditors. By 2020, this share had fallen to 11 percent.

- Over the same period, the share of DSSI countries’ external debt owed to China rose from 2 to 18 percent and the share of Eurobonds rose from 3 to 11 percent.

Chart 4

What does the creditor landscape in DSSI countries look like?

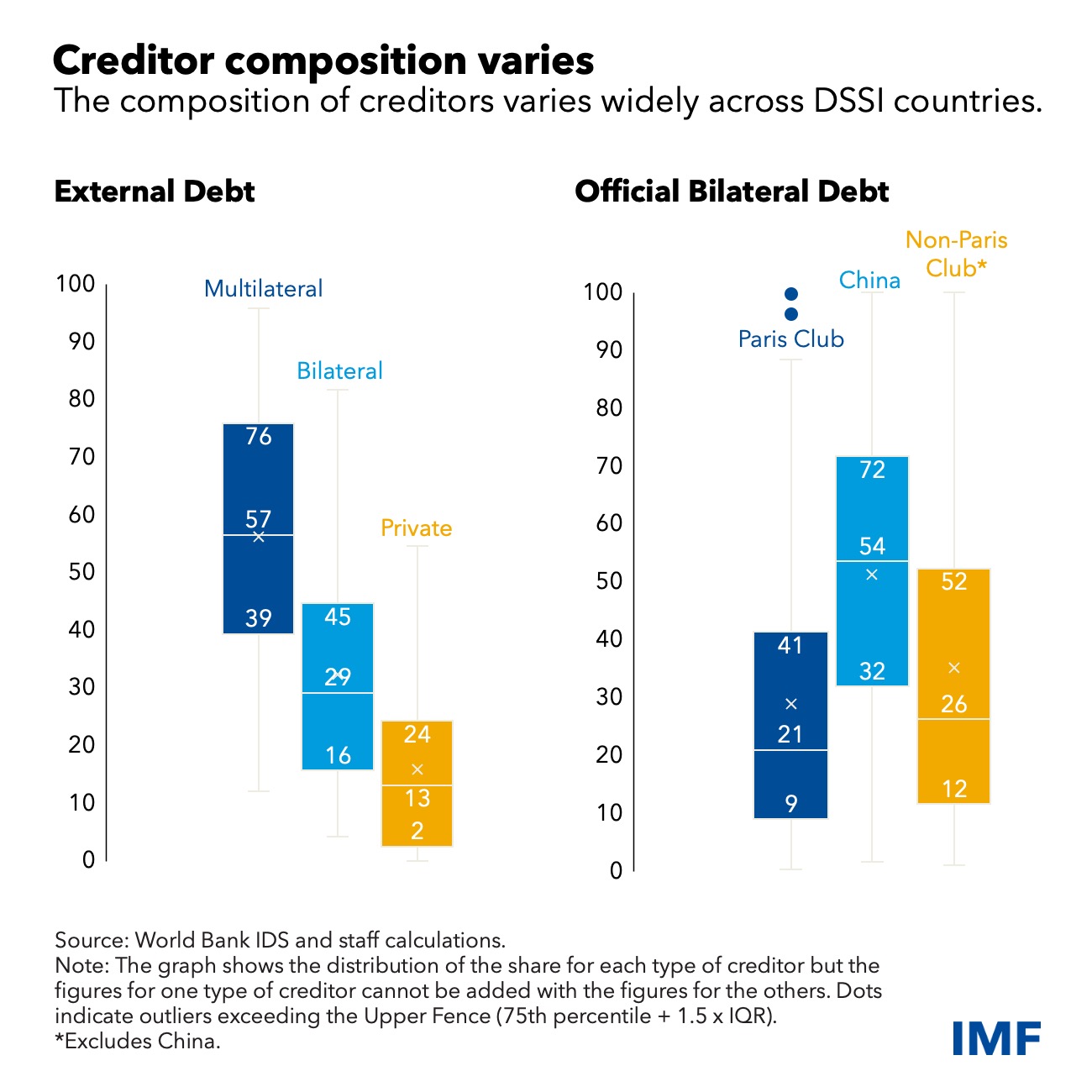

Creditor composition varies significantly among DSSI countries. This is reflected when looking at the distribution of the share of each major creditor or group of creditors in the total external debt of the 68 DSSI countries for which data is available (Chart 5).

Chart 5

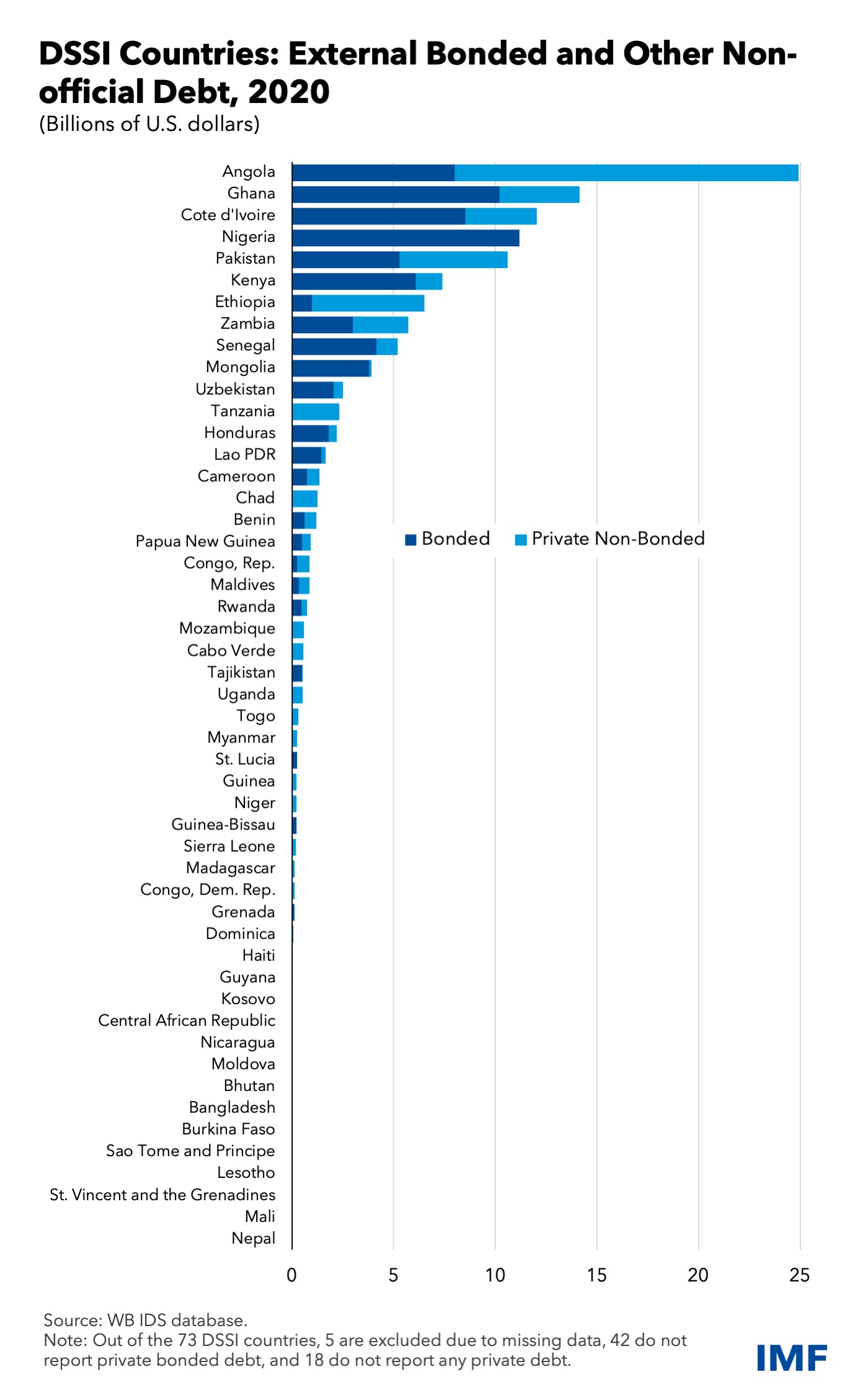

Private creditors’ exposures, in particular, are concentrated in a limited number of DSSI countries. Within the 68 DSSI countries for which data is available, 22 countries have a debt to private creditors that exceeds 15 percent of their total external debt, with these countries representing 83 percent of the total exposure of private creditors; only 26 countries report bonded debt; 18 do not report any private debt (Chart 6).

Chart 6

China’s exposure is also concentrated but its share among official bilateral creditors is such that it would play a key role in most debt restructurings involving these creditors. Within the 68 DSSI countries for which data is available, 22 countries have a debt to China that exceeds 20 percent of their total external debt. Reciprocally, these 22 countries represent 76 percent of China’s total exposure to DSSI countries. Of these, 6 countries (Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lao PDR, Pakistan, and Zambia) together account for about half of China’s total exposure to DSSI countries. That said, China is the biggest official bilateral creditor in more than half of the DSSI countries, including when counting all 22 Paris Club creditors as a single pool, with a median share of China in the total debt owed to official bilateral creditors reaching 43 percent. As such, China would play a key role in most DSSI countries’ debt restructurings that would involve official bilateral creditors.

What mechanisms need to be put in place to improve debt restructurings?

Debt restructurings in DSSI countries are likely to become more frequent and will need to consider the increased diversity of the creditor landscape in these countries. Having in place mechanisms that ensure coordination and confidence among stakeholders has become urgent. Improvements in the G20 Common Framework could play an important role in this objective. Being able to provide, where necessary, timely, orderly, and efficient debt restructurings is in the interest of the debtor countries as well as their creditors, and more broadly global stability and prosperity.

*Prateek Samal and Dilek Sevinc provided valuable research assistance.