Regional Highlights

- Special Report: The Economic Impact of Conflicts and the Surge in Refugees

- Middle East

- Europe

- Asia

- Africa

- Western Hemisphere

The dislocation of large parts of the population of Syria and other countries facing internal conflict has presented a humanitarian crisis that has had an immediate economic impact across the Middle East and Europe and beyond. For the IMF, the economic ramifications affecting so many members posed a challenge across several areas of its work. At its April 2016 meeting, the International Monetary and Financial Committee called on the Fund to “be prepared to contribute within its mandate” to managing the spillovers from “large refugee flows.” During FY2016, the first step was to gain a clearer understanding of the scope of the economic challenges in both the Middle East and Europe.

The Economic Impact of Conflicts and the Surge in Refugees

The dislocation of large parts of the population of Syria and other countries facing internal conflict has presented a humanitarian crisis that has had an immediate economic impact across the Middle East and Europe and beyond. For the IMF, the economic ramifications affecting so many members posed a challenge across several areas of its work. At its April 2016 meeting, the International Monetary and Financial Committee called on the Fund to “be prepared to contribute within its mandate” to managing the spillovers from “large refugee flows.” During FY2016, the first step was to gain a clearer understanding of the scope of the economic challenges in both the Middle East and Europe.

Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan and the Role of the Fund

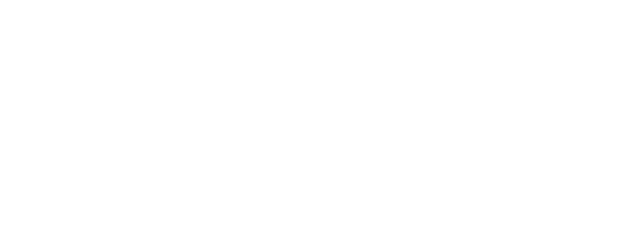

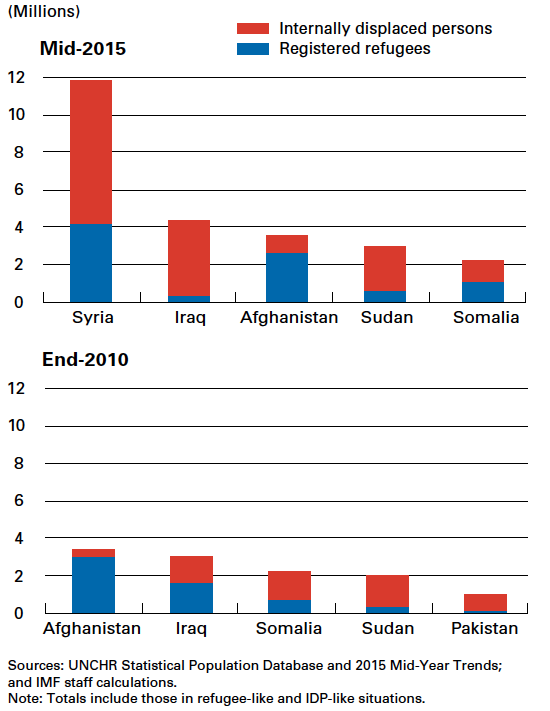

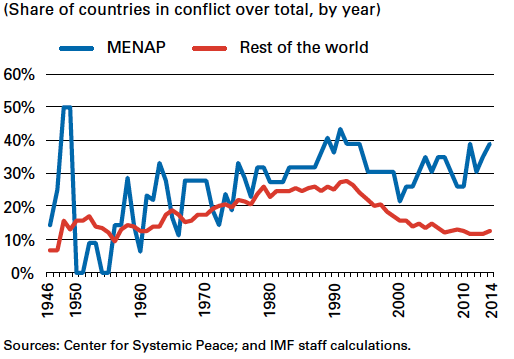

Conflicts continue to deepen in the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (MENAP) region. After receding during the 1990s, the scope and intensity of conflicts increased in the early 2000s. Conflicts have increasingly been internal, thereby affecting civilians, especially because of the expanding role of violent nonstate actors such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). The humanitarian costs have been immense. The United Nations estimates that more than 250,000 people have lost their lives and more than 1 million have been injured in the Syrian conflict alone. Conflicts displace millions: 19.3 million people were internally displaced in the region and 9.3 million MENAP citizens (not including Palestinian refugees) were registered as refugees with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, as of mid-2015 (see Figures 1.6–1.8).

Conflicts have had dire economic effects for both directly affected countries and their neighbors. Syria’s GDP today is less than half its prewar levels, while Yemen’s real GDP per capita is estimated to have contracted by more than 40 percent since 2010. According to the World Bank, the conflict in Syria has lowered Lebanon’s real GDP growth by nearly 3 percentage points every year since it started.

Conflicts affect economic activity through multiple channels. They reduce the stock of human and physical capital through casualties; the massive displacement of people; and destruction of infrastructure, buildings, and plants. They disrupt production and trade routes. They create uncertainty, thus undermining confidence. By weakening institutions and lowering stocks of human and physical capital, they also reduce potential growth. The poor and vulnerable are the most affected, as conflict-generated pressures on public budgets (for example, from increased security and military spending or—for neighboring countries—from hosting refugees) tend to crowd out social expenditure or lower the quality of public services.

The IMF has played a constructive role in mitigating the impact of conflicts, especially on neighboring countries. It has helped maintain macroeconomic stability and has supported international efforts to raise financing for countries hosting large numbers of refugees, such as Jordan. Over the long term, policy advice on coping with the economic consequences of conflicts, substantial financing, and capacity development will be critical for preventing macroeconomic collapse and supporting faster postconflict recovery and inclusive growth. In particular, the fund’s regional anchors for capacity development (the Middle East Regional Technical Assistance Center and Middle East Center for Economics and Finance) have the experience and expertise to help countries implement the reform measures needed to address structural impediments and to achieve higher and more inclusive growth.

Europe

The sudden surge of asylum seekers into Europe in FY2016 has presented a range of economic, security, political, and social issues. The surge has exposed flaws in Europe’s common asylum policy and has raised questions about the European Union’s ability to quickly integrate newcomers. The Fund addressed the economic issues in a February 2016 Staff Discussion Note, titled “The Refugee Surge in Europe: Economic Challenges.”

The note found that in the short term, the macroeconomic effect from the refugee surge is likely to be a modest increase in GDP growth, reflecting the fiscal expansion associated with support to asylum seekers, as well as the expansion in labor supply as the newcomers begin to enter the labor force. That effect is likely to be concentrated in the main destination countries (Austria, Germany, and Sweden). The impact of the refugees on medium- and long-term growth will depend on how they are integrated in the labor market. International experience with economic immigrants suggests that migrants have lower employment rates and wages than citizens of destination countries, though these differences diminish over time. Slow integration reflects factors such as lack of language skills and transferable job qualifications, as well as barriers to job searching.

For asylum seekers, legal constraints on work during the asylum application period also play a role. Factors that make it difficult for all low-skilled workers to take jobs—such as high entry wages and other labor market rigidities—may also be important, as may be “welfare traps” created by the interaction of social benefits and tax systems.

However, there are policies that can help open the path into the labor market: restrictions on taking work during the asylum application phase should be minimized and active labor market policies specifically targeted toward the refugees strengthened. Wage subsidies to private employers have often been effective in raising immigrant employment; alternatively, temporary exceptions to minimum or entry-level wages may also be considered. Initiatives to ease avenues to selfemployment (including access to credit) and facilitate skill recognition could also help refugees succeed.

Figure 1.6

Displaced persons in the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan

Figure 1.7

Frequency of conflict by region

Figure 1.8

Average intensity of conflict by region

Middle East and North Africa

Impact of Lower Oil Prices on Middle Eastern Oil Producers

Between 2004 and 2014, many oil producers in the Middle East enjoyed rapid economic growth supported by booming oil prices. With oil prices dropping more than 70 percent since mid-2014 and the expectation that they will remain “lower for longer,” these countries are facing an exceptionally challenging environment. Other factors, including regional conflicts and sluggish global growth prospects, are further complicating the outlook. How oil producers in the region could best adjust to the new oil price environment was the topic of the IMF staff ’s briefing to the Executive Board on March 2, 2016.

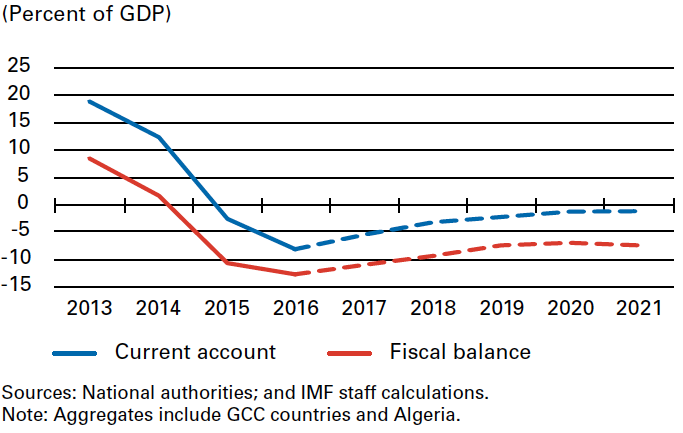

The plunge in oil prices has brought significant external and fiscal losses to the oilproducing countries in the region (Figure 1.9). Oil export revenues in the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) countries and Algeria, for example, declined by nearly $315 billion in 2015, and a further $130 billion decline is expected this year, with external balances projected to deteriorate by some 27 percent of GDP relative to 2013. Mirroring these losses, fiscal balances are projected to decline by some 21 percent of GDP in 2016 compared with 2013.

Initial policy responses mainly relied on the use of reserves. These were followed by significant deficit reduction measures during the second half of 2015, and this year’s budgets suggest policy efforts are intensifying. Adjustment has concentrated on reduced public spending, with several countries curbing capital expenditures, which boomed during the period of high oil prices. Many countries have also initiated substantial energy price reforms, which include raising utility prices and, in a few of them, introducing automatic pricing mechanisms. A number of countries are also considering new sources of revenue, with the GCC planning to introduce a value-added tax in the coming years.

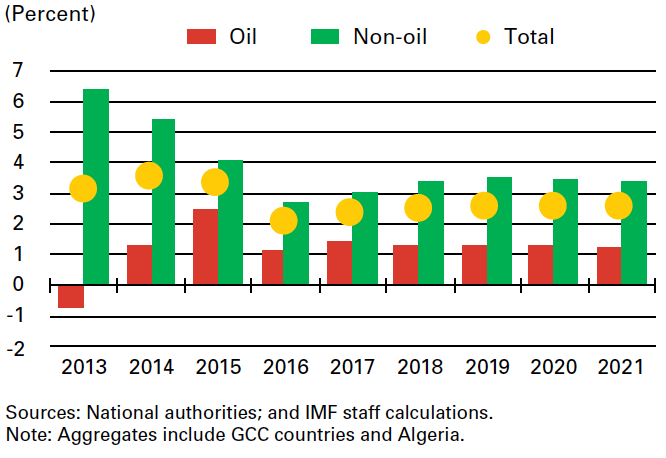

As the impact of lower oil prices is felt through tighter fiscal policy, growth in the region’s oil producers is expected to slow down substantially in 2016 and remain subdued in the coming years (Figure 1.10). In this environment, the need to reduce oil dependence has become even more critical. A growth model based on continued expansion in government spending and employment is no longer sustainable. Hence, policymakers need to step up policies that boost the role of the private sector in generating much-needed jobs and sustaining long-term growth to generate opportunities for the region’s rapidly growing labor force.

Figure 1.9

Oil-producing countries: Current account and fiscal balances

Figure 1.10

Oil-producing countries: Real GDP growth

Europe

Czech Republic: Sound Policies for Strong Fundamentals

Prudent fiscal, monetary, and financial policies helped the Czech Republic avoid the creditfueled domestic demand booms that engulfed most Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries in the run-up to the global financial crisis. However, the crisis did affect the Czech economy, which experienced a double-dip recession. The IMF’s annual economic reviews and policy advice served the country well: accommodative fiscal and monetary policies—in line with Fund advice—along with a favorable external environment helped the economy exit the recession in 2013 and expand at the highest growth rate in the CEE region in 2015. Having managed to reduce the country’s fiscal deficit to below the limit of 3 percent of GDP enshrined in European Union rules in 2013, the authorities subsequently eased its fiscal policy, which then supported the economy.

Monetary policy was also supportive. The Czech National Bank threw a lifeline to the economy, as it was among the first central banks in Europe to lower its policy interest rates to the zero lower bound. In its efforts to fight disinflationary pressures, the bank introduced an exchange rate floor as an additional instrument of its monetary policy arsenal. Although inflation is still well below the bank’s target, it has never fallen into negative territory.

The Czech economy is characterized by strong fundamentals. Both public and external debt are at moderate levels and on a declining path, contributing to country risk premiums at historic lows. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment in 2012 confirmed the strength of the Czech financial sector, and the authorities subsequently implemented the assessment’s recommendations. The banking sector is stable, with banks having strong capital and liquidity buffers and being mostly self-financed, with low rates of nonperforming loans. The Czech authorities have been striving toward greater transparency of policymaking.

The Czech Statistical Office has been publishing macroeconomic data in line with the IMF’s Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS) since 1998. It recently also joined the nine other advanced economies that adhere to SDDS Plus, which addresses data gaps revealed during the global financial crisis.

With support from IMF technical assistance, the Czech National Bank became one of the world’s leading inflation-targeting central banks. It is one of only five inflation-targeting central banks to publish a projected interest rate path, based on its staff forecast.

Ireland: Fiscal Adjustment Spurs Recovery

The Irish economy collapsed in 2008–10. Like other small open European economies, it was hit hard by both the global financial crisis and the subsequent euro crisis. But in Ireland’s case, the shocks came after a prolonged property boom that led to serious vulnerabilities: banks relied on flighty wholesale funding to lend aggressively to property developers, investors, and households; property prices had risen excessively; employment shifted into inflated construction and related sectors; and the government used property-driven revenues to raise spending and cut other taxes.

When the bubble burst, wholesale funding disappeared, lending seized up, property prices plummeted, and construction sites were abandoned. The unemployment rate tripled to 15 percent, revenues dropped 20 percent from 2007 to 2009, and the government faced huge deficits. Public debt soared as bank support reached 40 percent of GDP. By late 2010, Ireland had to request financial assistance from the European Union and the IMF. The Irish authorities had plans to underpin the fiscal adjustment needed to put public finances on a sound footing by reducing the deficit to no more than 3 percent of GDP over a five-year period. The IMF-supported program included reforms to restore Ireland’s banking system to health, including a bank recapitalization and a phased downsizing of bank assets— especially their foreign holdings—to bring them more in line with their deposits.

Amid the euro crisis, the economy remained weak well into 2012. But progress was made in narrowing the budget deficit; the program continually outperformed targets. By mid-2012, Ireland began to regain access to markets, first issuing Treasury bills and then lengthening maturities and expanding volumes in careful steps. By 2013, with the economy clearly recovering and confidence returning, Ireland was able to exit the IMFsupported program as scheduled. Soon after, it made early repayments to the IMF.

The Irish authorities’ decisive policy implementation and their ownership of the policies implemented gradually restored the confidence needed to restart hiring, investment, and growth. Indeed, with cumulative real GDP growth of 13 percent, Ireland was the fastest-growing economy in Europe during 2014–15, and steady job creation had brought the unemployment rate down to about 8.5 percent by early 2016.

Asia

Advancing Asia: Focusing on Asia’s Future

Asia … is the world’s most dynamic region and today accounts for 40 percent of the global economy. Over the next four years—even with slightly declining momentum—it stands to deliver nearly twothirds of global growth. Given this vital economic role, making the most of Asia’s dynamism is of great interest to the entire world.

— Managing Director Christine Lagarde at “Advancing Asia” conference in New Delhi, India

The IMF gave in-depth attention to crucial policy issues facing the Asia-Pacific region at two conferences held during FY2016, the first stage of a focus on Asia leading up to the 2018 IMF–World Bank Annual Meetings in Indonesia.

Economic and social progress

Representatives of countries throughout the Asia-Pacific region gathered in New Delhi, India, in March 2016 for the Advancing Asia conference, jointly organized by the IMF and government of India. The three-day gathering took stock of the region’s economic performance and the issues that will have a great bearing on social and economic progress in Asia in the coming years.

Participants included senior government officials, corporate executives, the leadership of international organizations, academics, and civil society representatives. The Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, and Managing Director Christine Lagarde gave keynote speeches. The topics discussed at the conference included Asian growth models; income inequality, demographic change, and gender issues; infrastructure investment; climate change; managing capital flows; and financial inclusion.

At the event, the Fund and India announced an agreement to set up the South Asia Regional Training and Technical Assistance Center (SARTTAC) to strengthen capacity development in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. The memorandum of understanding signed by the Fund and India was a key step toward establishing a fully integrated capacity development center in New Delhi.

Financial sector innovation

The challenges of sustaining Asia’s impressive growth performance through financial sector innovation and financial inclusion served as the centerpiece of a conference held in Jakarta, Indonesia, in September 2015. Future of Asia’s Finance: Financing for Development, jointly organized by the IMF and Indonesian government, focused on integrating and deepening of financial markets to enhance stability and support infrastructure investment. It also explored the policies that can enhance financial inclusion to spread the fruits of Asian prosperity more widely. The IMF published a book titled The Future of Asian Finance for the conference.

Nauru Becomes 189th Member

The Republic of Nauru became the IMF’s 189th member in April 2016, at a ceremony held in Washington, D.C.

Nauru will be the second-smallest member of the Fund, after Tuvalu, as measured by its quota subscription of SDR 2 million ($2.81 million). This will be the case after it pays for its quota increase under the Fourteenth General Review, which will increase its quota to SDR 2.8 million. The country, located in the Pacific Ocean, has a population of about 10,500 and a land area of about eight square miles. Nauru is also the smallest sovereign state in the world after Vatican City in terms of both population and area.

Nauru’s economy relies on phosphate mining, the Australian Regional Processing Center for asylum seekers, and revenue from fishing license fees. In recent years, growth has been strong, mainly driven by the center’s operations and phosphate exports, although it moderated in 2015. Membership allows the IMF and other development partners—the country has also joined the World Bank—to help the authorities implement economic reforms and tackle development challenges. The country will participate in an annual IMF review of its economy and benefit from cross-country analysis and, potentially, access to IMF lending. Nauru receives technical assistance from the IMF, including through the Fund’s Pacific Financial Technical Assistance Center, based in Fiji.

Helping Nepal Recover from a Devastating Earthquake

Nepal is still struggling to recover from the country’s worst earthquake in more than 80 years. The magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck an area northwest of the capital, Kathmandu, on April 25, 2015. More than 300 aftershocks greater than 4.0 followed. Almost 9,000 people were killed, 2,300 more were injured, and hundreds of thousands were left homeless.

An estimated 8 million people have been affected by the disaster, poor rural areas more heavily than towns and cities because of lower-quality housing construction. Many cultural and architectural heritage sites were heavily damaged.

Swift IMF response

Immediately after the earthquake, Managing Director Christine Lagarde promised to send an IMF team on short notice. The IMF mission arrived in Kathmandu two weeks after the earthquake to assess the macroeconomic impact and discuss balance-of-payments and fiscal needs associated with the rehabilitation and reconstruction effort. The mission team was meeting with Ministry of Finance officials on May 12, 2015, when an aftershock measuring 7.3 hit.

Financial support from the IMF

At an international donor conference in June 2015, Nepal received pledges of external support for reconstruction in the form of grants and loans totaling some $4 billion. On July 31, 2015, the IMF Executive Board approved a request from the Nepalese authorities for a $50 million loan to help the country address the devastation. The money was provided under the Rapid Credit Facility at the Fund’s concessional interest rate (currently 0 percent), with a grace period of five and a half years.

Expanding Use of Financial Soundness Indicators

The IMF’s Financial Soundness Indicators (FSIs) help assess the strengths and vulnerabilities of financial systems, providing valuable insight for financial stability analysis and the formulation of macroprudential policies. Fund staff members are required to report on FSIs as part of their regular reviews of countries’ economic health.

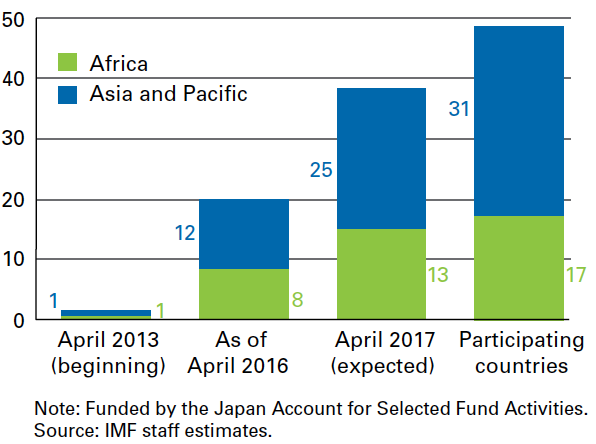

Thanks to funding from Japan, the IMF is delivering capacity-development support to 48 member countries in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands to assist with the compilation and dissemination of FSIs according to international standards. After three years of project implementation, 20 of the participating countries now meet the standards, and by the end of the project period (April 2017), another 18 are expected to do so as well (see Figure 1.11).

Through lectures and hands-on and data-intensive workshops conducted during regional training sessions, participants learn from both IMF experts and peers. The latter are an especially effective means of delivering capacity development in regard to the indicators because regulators, who generate some of the source data, and compilers have much in common in terms of the issues they face.

The IMF has held FSI workshops in Fiji, Namibia, Senegal, and Thailand. Bilateral technical assistance is provided when a country-specific focus is a more efficient way of developing capacity.

In addition, the work on FSIs leverages the resources provided by the United Kingdom’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Development for the module on FSIs under the Enhanced Data Dissemination Initiative 2. The module covers 22 member countries in Africa and the Middle East and Central Asia.

Figure 1.11

Financial Soundness Indicators: Participating and reporting countries

Africa

Mobile Banking

Mobile money and banking have taken off in the past few years in the East African Community, especially in Kenya and Tanzania. The provision of payment services through mobile platforms—known as mobile money—has expanded access to financial services: according to the 2013 FinScope surveys, nearly two-thirds of adults in both countries now have access to the formal financial system, largely due to mobile money. Mobile money and banking has also had a positive impact on the population by reducing the cost of transfers to rural areas and improving security by replacing the previous practice of carrying cash over long distances.

Services in this area are expanding rapidly beyond simple money transfers. In Kenya, people can now build up savings deposits by linking mobile platforms to bank accounts. This allows households and small and medium-sized enterprises, which previously had difficulty qualifying for traditional bank accounts, to save and establish a track record that can help them get small loans in the future. Mobile transactions now exceed 50 percent of GDP in both Kenya and Tanzania, and there are plans to roll out additional value-added services, including capital market tools.

The IMF has played a supportive role in the evolution of mobile money and banking through its research and technical assistance, mainly in ensuring that these platforms are secure and well regulated in order to strengthen confidence. The Fund also has ongoing discussions with country authorities about the impact of mobile money and banking on member economies, and assessing, formulating, and implementing monetary policy.

African Journalists Hone Economic Reporting Skills

To help make economic and financial information more accessible to Africans and improve understanding of the Fund’s work, in FY2016 the IMF organized two training workshops for journalists in the region. Twenty journalists from the eight countries in the West African Economic and Monetary Union and Guinea attended a session in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, and 15 Zimbabwean journalists participated in training in Harare. The participants—from print, radio, television, and online publications—represented the broad range of private and public media in those countries.

Using a hands-on approach to the training, participants produced stories in real time. The topics included the role of a central bank and how it helps steer an economy, economic cycles and how to report economic news in a challenging environment, and debt restructurings. The journalists came away with a better understanding of how the IMF works and how to report on its activities. Participants in the Abidjan workshop subsequently moved to strengthen collaboration among journalists across the region by creating the network of West African Economic and Financial Journalists (COAJEF).

- Box 1.5: How can countries learn from their peers?

-

Some 40 developing countries have sustained high growth rates since 1990 to achieve or move toward emerging market status. Their economic strategies have rested on integration into the global economy and creating space for small and medium-sized enterprises and foreign direct investment.

As Senegal aspires to join this group, President Macky Sall has developed the Plan Sénégal Emergent, which aims at enabling Senegal to achieve middle-income status by 2035.

The IMF has helped Senegal work with peers from middle-income countries in Africa to learn from their experience. In 2014 peers from Cabo Verde, Mauritius, and Seychelles, along with World Bank and Fund experts, helped Senegalese colleagues clarify the reforms needed to implement the plan, a strategy that could be supported by a new IMF program under the Policy Support Instrument.

In early 2016, with European Union support, the IMF organized a book-writing exercise in Washington, D.C., that brought together 10 Senegalese authors from government and academia, along with colleagues from the peer countries and the World Bank.

The exercise produced a first draft of a book (to be published at the end of 2016) on the political economy of reforms. The book discusses (1) creating a sound and efficient fiscal framework through revenue-raising measures, expenditure rationalization, and more efficient public investment; (2) relieving constraints on doing business and encouraging private small and medium-sized enterprises and foreign direct investment; (3) promoting an inclusive financial sector; and (4) achieving high, sustained, and inclusive growth.

Senegal’s Prime Minister subsequently chaired a ministerial meeting that mandated the Senegalese authors to formulate, with support from development partners, interventions to facilitate the political economy that would make reform implementation feasible. Budget support could then be mobilized to finance these interventions.

Enhanced Data for Better Macro Policies

The production of timely and high-quality data is crucial in enabling all countries to better reflect changes in their economies and provide relevant tools for policy formulation and impact assessment. Africa has made headway in improving the quality of its data, but there is still room for African countries to enhance data timeliness, periodicity, coverage, reliability, and dissemination.

The production and dissemination of high-quality macroeconomic statistics is largely undermined by weak source data. Other challenges include low levels of investment in necessary skills, lack of sufficient information technology capacity, difficulties measuring the informal economy, and inadequate institutional and legislative frameworks.

To support countries’ efforts to improve the quality of their data, the IMF has been providing technical assistance and training. The Fund has assisted more than a dozen countries in the last two years in rebasing their national accounts, and another dozen or so countries as they produce quarterly national accounts. Plans are underway to help countries in the East African Community prepare for another round of GDP rebasing, a rebenchmarking of the gross domestic product national account series, which helps GDP data reflect a more current snapshot of the economy.

- Box 1.6: How can better data help African policymakers?

-

The IMF played a key role at the February 2016 Accra conference on “Enhanced Data for Better Macro Policies,” organized jointly with the government of Ghana, the IMF Statistics Department, and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development. At the conference, senior officials from more than 40 African countries, as well as representatives from academia, banks, rating agencies, think tanks, and international organizations, debated the data challenges facing African policymakers. Participants committed to promoting the dissemination of data for enhanced evidence-based economic decision-making and discussed the way forward.

Topics included transparency and comparability of statistics, integrity and independence of the institutions producing statistics, and promoting the production of timely, high-quality data for the benefit of policymakers. Participants urged national authorities to take ownership of statistics and give higher priority to their production in national budgets.

Reflecting the significance that senior officials attached to this conference, Kenyan Central Bank Governor Patrick Njoroge stated, “The conference provided a unique opportunity for high-level decision-makers to exchange ideas and experiences so that we can work together to strengthen the data used for policymaking.”

In addition, the IMF is assisting central banks in eastern and southern Africa in producing high-frequency indicators to enhance monetary policy formulation. In east Africa, the IMF is helping member countries develop an action plan to implement the Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014 (GFSM 2014), including an integrated statistical system that is intended as a reference volume describing the government financial statistics system. The Fund is supporting the West African Economic and Monetary Union and Central African Economic and Monetary Community in compiling a government financial operations table that is consistent with the GFSM 2014. These regional efforts are expected to improve monitoring of convergence criteria in these economic communities.

With trust fund support, the IMF is developing a Guide to Analyze Natural Resources in the National Accounts. The guide is a tool to analyze the macroeconomic impact of natural resources on output and prices. It will provide policymakers and the public at large with key analytical information needed to understand actual or potential macroeconomic impacts of changes in natural resources. It will also assist national accounts compilers in resource-rich economies by helping to reveal errors, omissions, and inconsistencies in measuring transactions related to natural resource wealth and its extraction.

With the support of the International Labour Organization, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, and other international organizations, the IMF’s Statistics Department and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development launched a joint project to collect consumer price index data. Launched in February 2016, data for more than 100 countries are available on the IMF website (http://0-data-imf-org.library.svsu.edu/CPI). The project makes more data available and eases the burden on data reporters through data sharing among international organizations.

Western Hemisphere

Dominica: Tropical Storm Erika and the IMF Response

Tropical Storm Erika hit Dominica on August 27, 2015, killing dozens and causing widespread devastation. Flooding and landslides severely damaged roads, bridges, and the main airport. The storm also crippled the water and sewage network and seriously affected agriculture and tourism. The total damage and loss was estimated at 96 percent of GDP, including about 65 percent of GDP in reconstruction costs.

Soon after the storm, the Dominican government requested emergency financial assistance from the IMF. On October 28, the IMF Executive Board approved a disbursement of SDR 6.15 million ($8.7 million), representing 75 percent of quota, the maximum annual access limit allowed at the time under the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF), to address urgent balance-ofpayments and fiscal needs. The RCF provides low-access, rapid, zero-interest financial assistance to low-income countries facing an urgent balance-of-payments need so as to enable them to make progress toward achieving or restoring stable and sustainable macroeconomic positions consistent with strong and durable poverty reduction and growth. Unlike other IMF instruments of financial support, the RCF does not have conditionality in the form of performance criteria or structural benchmarks.

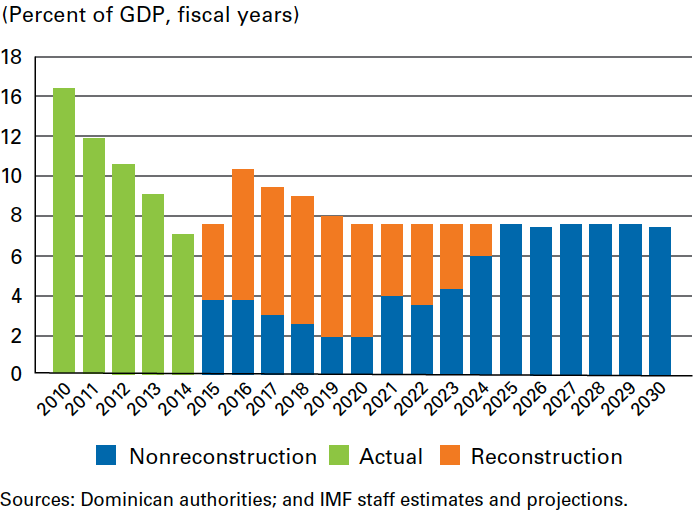

The IMF also provided technical support in developing a sustainable macroeconomic framework to accommodate the extensive storm-related expenditures and assistance required to meet pressing social needs (Figure 1.12). The planned reconstruction is estimated at about 50 percent of GDP over seven years, with smaller amounts thereafter. It will be financed by new fiscal measures and donor funding.

Dominica has a high level of public debt (80 percent of GDP), and the authorities intend to achieve the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union public debt target of 60 percent by 2030. To this end, the government is working on a medium-term plan that will include measures to improve the fiscal balance by about 6 percent of GDP over a period of five years, with the support of a macroeconomic advisor financed by Canada. A fiscal balance buffer of about 1.5 percent of GDP will provide a cushion for any additional reconstruction expenditures so that Dominica is better prepared for other natural disasters in the future.

The IMF participated in a donor conference held in Dominica on November 16, 2015, with other official creditors and representatives of several countries willing to provide financial assistance. Many bilateral partners promised generous contributions, but additional grants still need to be identified in order to finance the huge reconstruction costs. The IMF remains hopeful that the government’s commitment to a sustainable macroeconomic framework will trigger additional donor support.

Figure 1.12

Dominica: Capital expenditures, reconstruction and other

Guatemala: Stabilizing Prices for Higher Living Standards

IMF technical assistance has helped Guatemala overcome a legacy of high inflation. The Fund’s support has enabled Guatemala’s central bank to sharpen its monetary policy tools and bring its monetary operational framework in line with best international practices. It contributed to the country’s adoption of an inflation-targeting regime, for example, by developing capacity among central bank staff for macroeconomic analysis and forecasting.

Thanks to reforms resulting in part from the technical assistance, inflation fell to about 3 percent at the end of 2015, compared with the very high levels of the mid-1980s and early 1990s, peaking at 60 percent in 1990. The Guatemalan authorities responded with a strategy, launched in 1991, to bring down inflation and strengthen the country’s external position. The strategy included fiscal adjustment, constitutional and legal reforms to prevent the central bank from continuing to finance the government either directly or indirectly, interest rate liberalization, introduction of a flexible exchange rate system, and strengthening central bank independence. Last year, market interest rates fell by more than 10 percentage points, making it easier for borrowers to access credit. This allowed financial deepening to increase from 20 percent of GDP in 2000 to 35 percent of GDP in 2015, and the purchasing power of an average middle-income family rose from $5,000 in 2000 to $7,737 in 2015.

Today, Guatemala’s track record for macroeconomic stability, broadly recognized internally and abroad, is one of the country’s most important assets for attracting private investment and fostering economic growth for the benefit of the population.

2015 Annual Meetings in Lima

More than 10,000 people from around the world gathered in Lima, Peru, for the October 2015 IMF–World Bank Annual Meetings.

The meetings, the first to be held in South America since the 1967 meetings in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, came at a time of concerns about major transitions in the global economy—particularly China’s rebalancing, low commodity prices, and a shift in U.S. monetary policy. In response, the Fund called for a “policy upgrade” to respond to the uncertain outlook, advising policymakers to focus on supporting demand, financial stability, and structural reforms.

Managing Director Christine Lagarde spoke at the Annual Meetings on the importance of strengthening the IMF by making it a more agile, integrated, and member-focused institution (a set of goals shortened to “AIM”). “Working together, I know that we can—and will—deliver,” she said. Lagarde also highlighted the importance of enacting the 2010 quota reforms, which reached the necessary thresholds for approval by the membership soon after the Annual Meetings.

As with other Annual Meetings, a center of attention for attendees was the Program of Seminars, which featured seven IMF flagship events that addressed topics ranging from climate change to financial inclusion to the Post-2015 Development Agenda to public sector governance.

The meetings also shone a spotlight on changes and challenges in Latin America. In various settings— including the Program of Seminars—the Fund and outside experts explored the need for the region to develop new opportunities to strengthen economic growth while preserving and enhancing social gains. The Annual Meetings also served as an occasion to showcase Peru’s economic achievements and to celebrate its traditions and rich cultural diversity.