In our blog at the beginning of this year, we flagged that emerging markets were navigating high global interest rate volatility. We also noted that while emerging markets have thus far remained resilient, rising uncertainty could lead to challenging times ahead.

A global soft landing remains the base case, as the July World Economic Outlook update showed. The forecast for economic growth in emerging markets has changed little, with projections edging up to 4.3 percent for both this year and next. Inflation in most major emerging markets is forecast to ease further and reach target ranges, allowing monetary policy to ease in the foreseeable future.

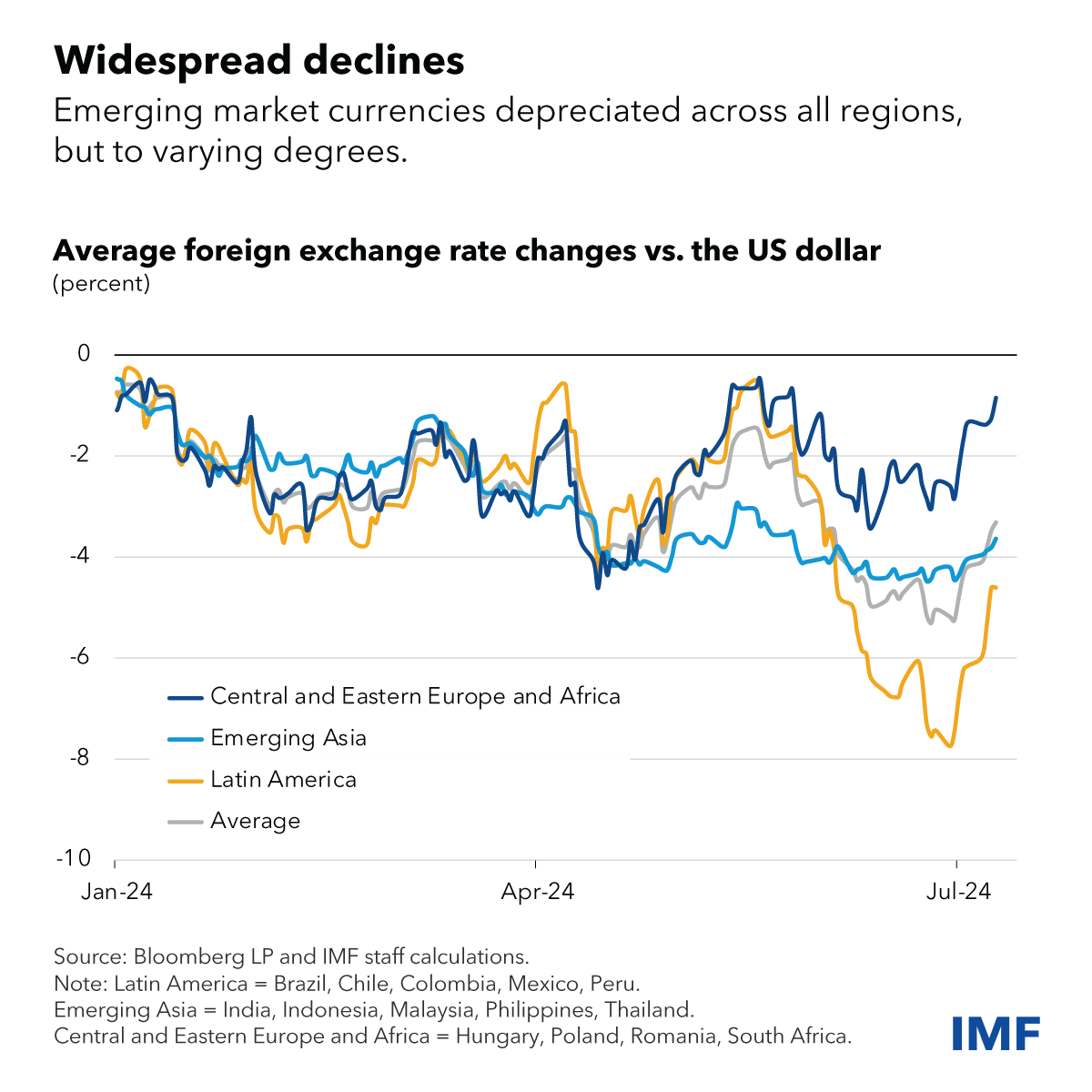

And yet, emerging market currencies have declined by about 4 percent year-to-date, on net, against the US dollar, even after partially recovering in recent weeks. Latin American currencies have dropped 5 percent, while currencies in Asian emerging markets are lower by 4 percent. Central and Eastern European and African currencies saw milder depreciations. It’s important to assess whether further declines could have adverse consequences for financial stability.

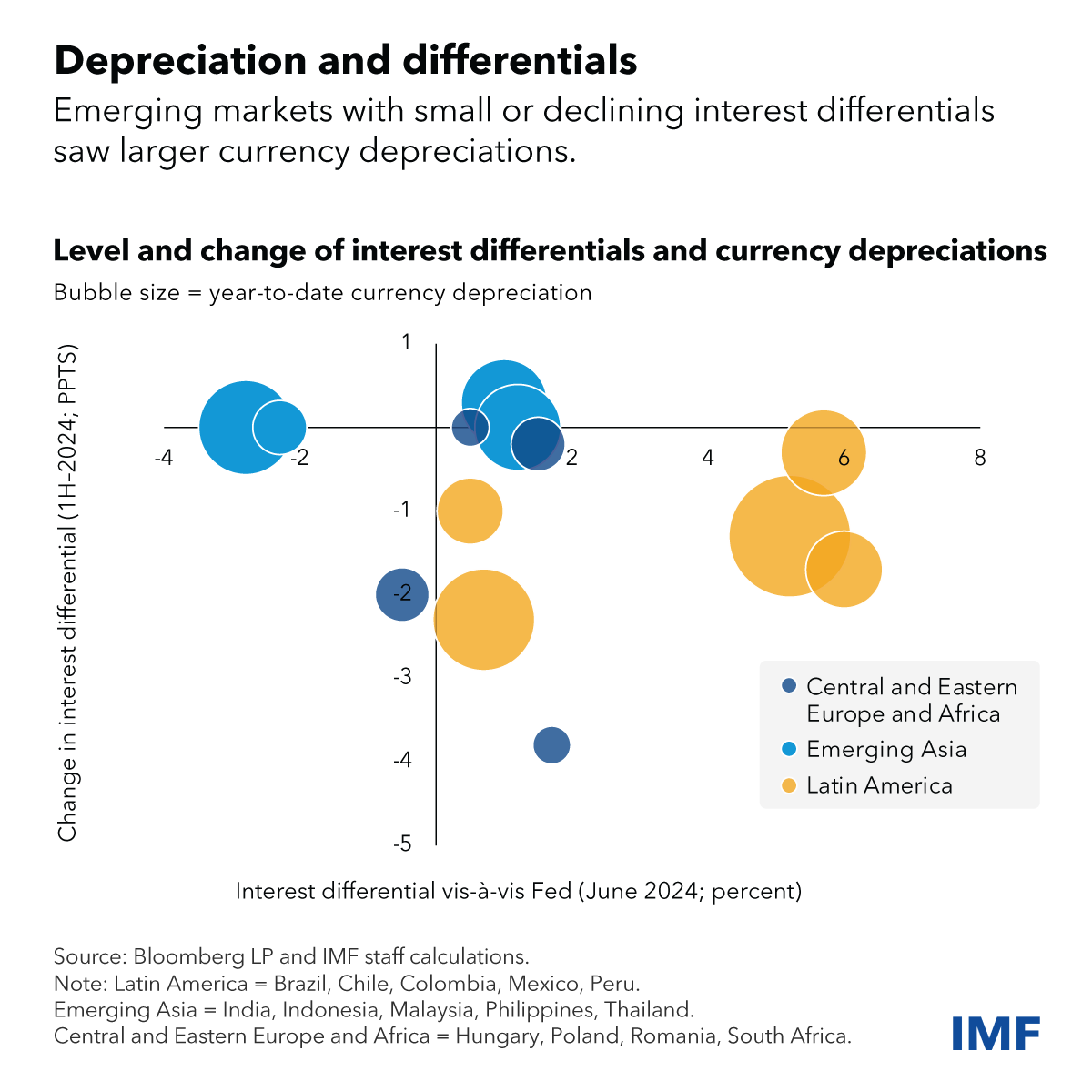

A key determinant of exchange rates is the difference in interest rates between a given country and the United States—the benchmark in global capital markets. At the beginning of this year, investors expected the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates significantly, which would widen or at least maintain the interest differentials with emerging markets. With the US economy proving stronger than previously anticipated and inflation not yet reaching the Fed’s target, expectations for US interest rate cuts dissipated over the course of the year, and the US dollar appreciated. As a result, major emerging markets’ interest rate differentials vis-à-vis the US narrowed.

Countries with the most pronounced narrowing—notably several Latin American countries that reduced policy rates this year in response to slower inflation—or those that have the lowest levels of interest rate differentials, including some Asian emerging markets, experienced the largest exchange rate depreciations against the dollar. Other country-specific factors might also be at play, such as fiscal concerns or political developments. Several emerging central banks have slowed or paused rate hike cycles, or conducted foreign exchange interventions, to manage currency volatility.

The past six months underscore the importance of the interest rate differential as a fundamental driver of exchange rates. Currency depreciations can occur even when the economic outlook for a country is solid, because it is the relative level of interest rates that matters most.

These adjustments also demonstrate that most emerging market central banks remain committed to policy frameworks that target domestic inflation and economic conditions, rather than exchange rates per se. Faithful adoption of inflation targets may in fact lessen the pass-through of currency depreciations to domestic conditions, as shown by the recent work by IMF’s Regional Economic Outlook team. That said, exchange rate volatility continues to be a part of the policy deliberations. Several major emerging market central banks have recently discussed exchange rate volatility and global uncertainty as part of their decision making.

Currencies and financial stability

Orderly depreciation of a currency toward levels broadly in line with economic fundamentals—including interest rate differentials—can be constructive for an economy. More troubling are cases where there are abrupt selloffs, which can trigger financial instability. Sudden foreign capital outflows can severely affect asset prices and open up funding gaps. Financial institutions could see foreign exchange mismatches intensify and may be unable to rollover foreign currency (particularly US dollar) funding at reasonable costs. Investor confidence in emerging economy financial markets could quickly falter.

Thankfully, that hasn’t been the case this year.

Yet with an uncertain global backdrop, and markets increasingly sensitive to economic data releases, central bank communications, and political uncertainty in some major economies, outflow pressures could spike suddenly. This could leave emerging market policymakers with the potentially difficult trade-off between stabilizing domestic conditions and fending-off external pressures.

Policy responses to maintain financial stability

Should pressures continue to build, additional policy tools can be useful—in line with the IMF’s Integrated Policy Framework. For instance, in cases where a sharp depreciation poses material financial stability risks owing to balance-sheet mismatches, or threatens to de-anchor inflation expectations, foreign exchange intervention may be helpful in mitigating adverse impacts. Such interventions can be especially useful when markets are shallow or outflows cause market liquidity to seize up. If the situation deteriorates to imminent crisis, capital flow management measures might be needed as part of a broader policy package to alleviate outflow pressures.

However, these measures can’t substitute for fundamental macroeconomic adjustments and should be only part of broader plans to address any underlying imbalances. For example, policymakers in several countries have communicated that recent interventions were the exception, not the rule. Macroprudential policies—for example those targeting asset and home prices, as well as those reducing FX mismatches on borrower balance sheets—could be potent complements. And stress tests aimed at identifying systemic troubles in the financial sector arising from external pressures could help mitigate risks before they materialize.

Most importantly, prudent policymaking should not only be about the baseline, but also about risk management. Vigilance and planning for adverse scenarios should be the central tenet of financial policies.