As Russia’s war in Ukraine takes a rising toll on Europe’s economies, growth is flagging across the continent, while inflation shows little sign of abating.

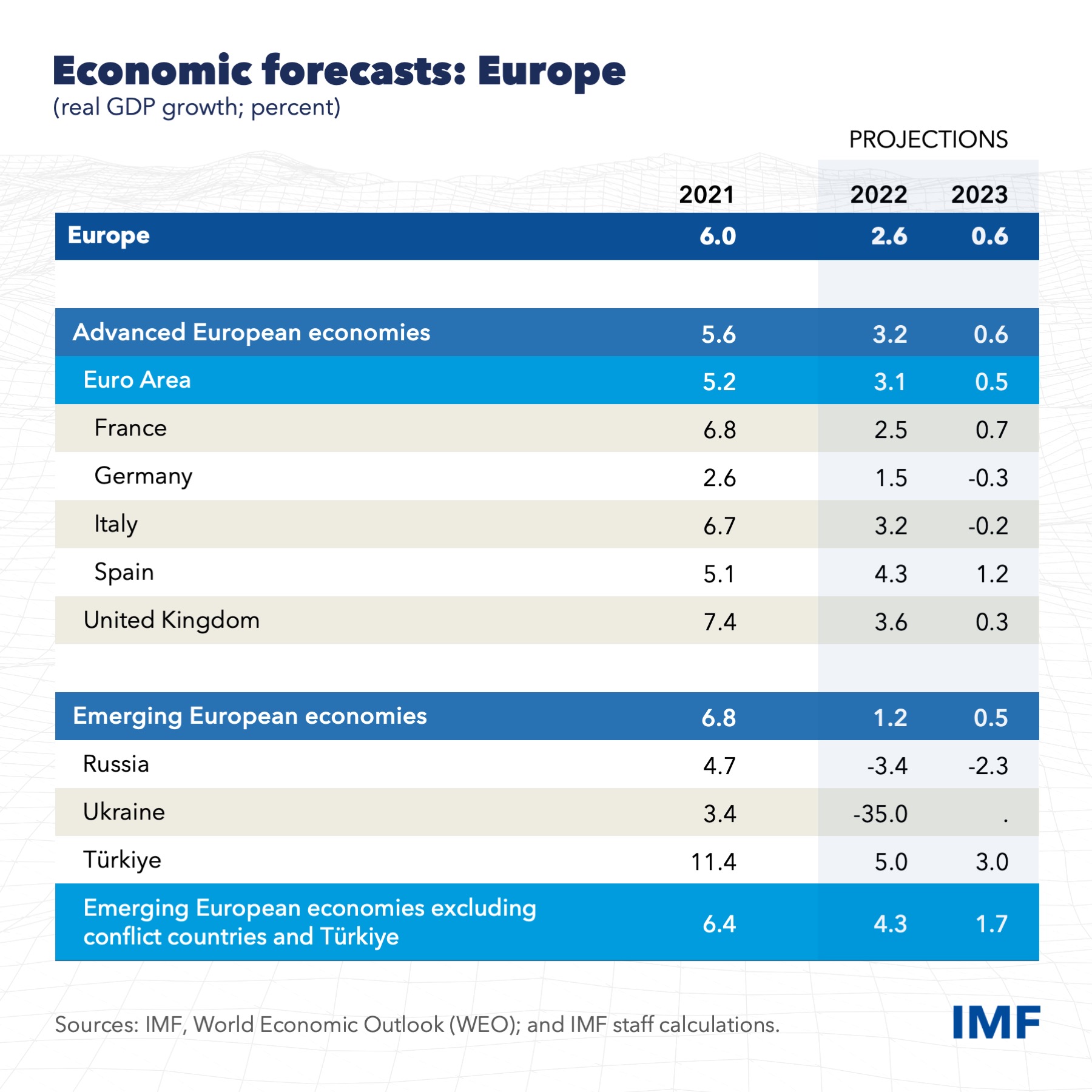

Europe’s advanced economies will grow by just 0.6 percent next year, while emerging economies (excluding Türkiye and conflict countries Belarus, Russia, Ukraine) will expand by 1.7 percent, according to projections in our latest World Economic Outlook. That’s down by 0.7 percentage point and 1.1 percentage points, respectively, from July’s projections.

This winter, more than half of the countries in the euro area will experience technical recessions, with at least two consecutive quarters of shrinking output; among these countries, output will fall, on an average, by about 1.5 percent from its peak. Croatia, Poland and Romania will experience technical recessions as well, with an average peak-to-trough output decline of more than 3 percent. Next year, Europe’s output and income will be nearly half a trillion euros lower as compared to the IMF’s pre-war forecasts—a stark illustration of the continent’s severe economic losses from the war.

And while inflation is projected to decline next year, it will stay significantly above central bank objectives, at about 6 percent and 12 percent, respectively, in advanced and emerging European economies.

Growth and inflation could both get worse than these already sobering forecasts. European policymakers have swiftly responded to the energy crisis and built adequate gas storage ahead of the heating season, but further disruptions to energy supplies could lead to more economic pain.

Our scenarios show that a complete shutoff of remaining Russian gas flows to Europe, combined with a cold winter, could result in shortages, rationing and gross domestic product losses of up to 3 percent in some central and eastern economies. On top of these, it could also result in yet another bout of inflation across the continent.

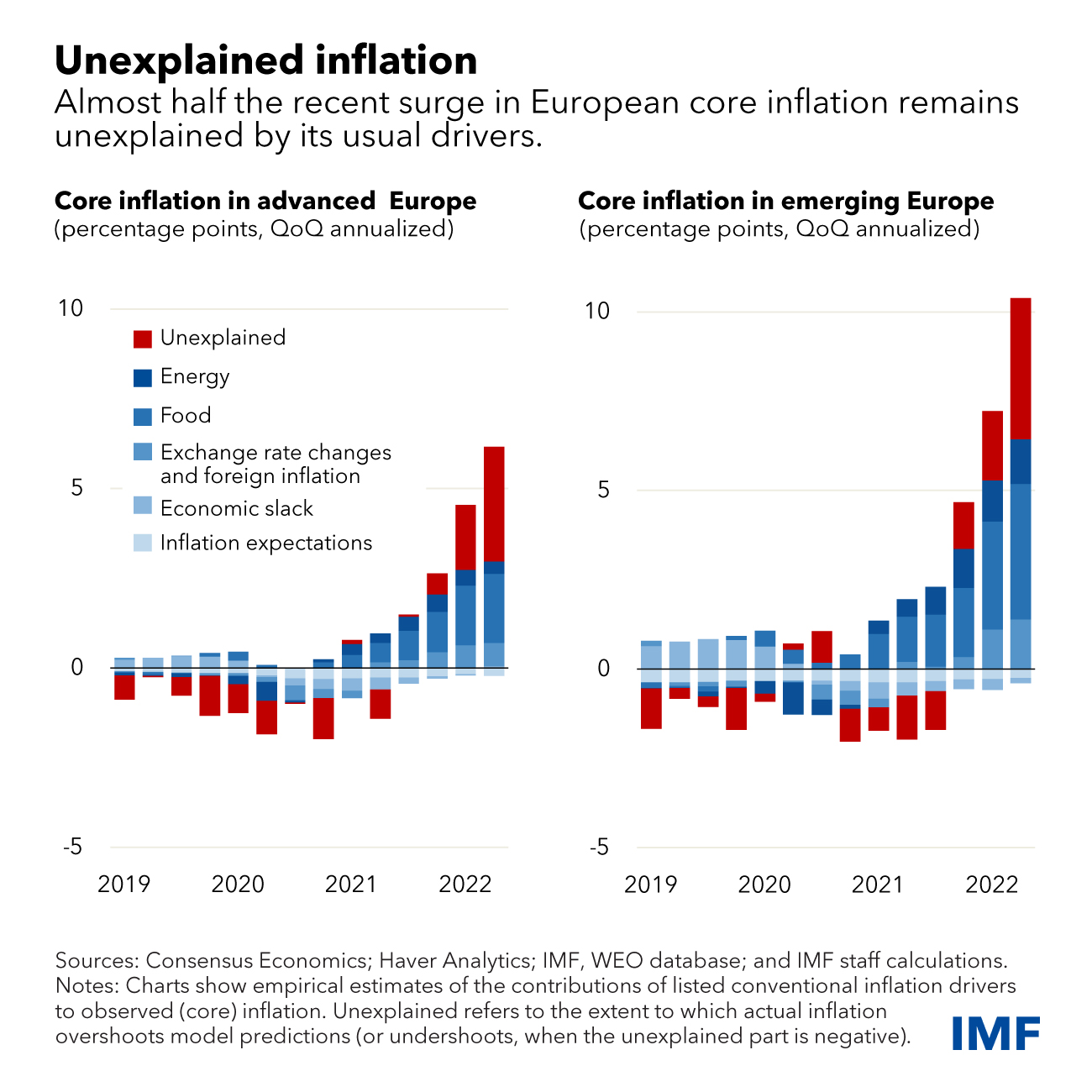

Even without any new energy supply disruptions, inflation could remain higher for longer. Most of the inflation surge so far is driven by high commodity prices—primarily energy, but also food, particularly in the Western Balkan countries. While these prices might remain elevated for some time, there is hope that they will stop increasing and thereby contribute to a steady decline in inflation throughout 2023.

Inflation risks

However, our latest Regional Economic Outlook shows that the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine might have fundamentally altered the inflation process, with rising input and labor shortages contributing notably to the recent high-inflation episode. This suggests there may be less economic slack and, accordingly, more underlying inflationary pressures, than commonly thought across Europe.

These results highlight a risk to our forecasts and those by others that inflation will fall steadily next year. Other wild cards include a de-anchoring of medium-term inflation expectations, or a much sharper acceleration in wages that would trigger an adverse feedback loop between prices and wages.

European policymakers face severe trade-offs and tough policy choices as they address a toxic mix of weak growth and high inflation that could worsen.

In a nutshell, they should tighten macroeconomic policies to bring down inflation, while helping vulnerable households and viable firms cope with the energy crisis. And, in these extraordinarily uncertain times, stand ready to adjust policies in either direction in response to how the situation evolves. This will depend on whether incoming data signal higher inflation, a deepening recession—which would warrant some reconsideration of policy—or both.

Central banks should continue raising policy rates for now. Real interest rates remain generally accommodative, labor markets are projected to be broadly resilient, inflation forecasts are above target, and inflation is still at risk of further increase.

Tightening needed

In advanced economies, including in the euro area, tight monetary policy will likely be needed in 2023 unless activity and employment weaken more than expected, materially bringing down medium-term inflation prospects.

A tighter stance is generally warranted in most emerging European economies, where inflation expectations are not as well anchored, demand pressures are stronger and nominal wage growth is high—often in the double digits.

Continuing to raise policy rates for now is also an insurance policy against risks, including a de-anchoring of inflation expectations or a feedback loop between prices and wages, that would require even stronger and more painful central bank responses down the road.

For example, in advanced European countries, our analysis suggests that if workers and firms start setting wages based on past inflation rather than central bank targets—as was partly the case prior to the 1990s, inflation could be nearly 2 percent higher at the end of next year. Should this happen, policy rates may need to rise by 2 percentage points and output could fall by as much as 2 percentage points more than currently projected. By contrast, if the overall demand declines—more than expected—resulting in deeper recessions and a 2 percentage points increased drop in output, both inflation and required policy rates at the end of next year could be nearly 1.5 percentage points lower than anticipated.

Fiscal policy

Fiscal policy must balance competing objectives. One is the need to rebuild fiscal space and help monetary policy in its fight against inflation. This calls for fiscal consolidation to proceed in 2023 at a faster pace in countries with less fiscal space, greater vulnerability to tighter financial conditions or stronger cyclical positions. This includes most emerging European economies.

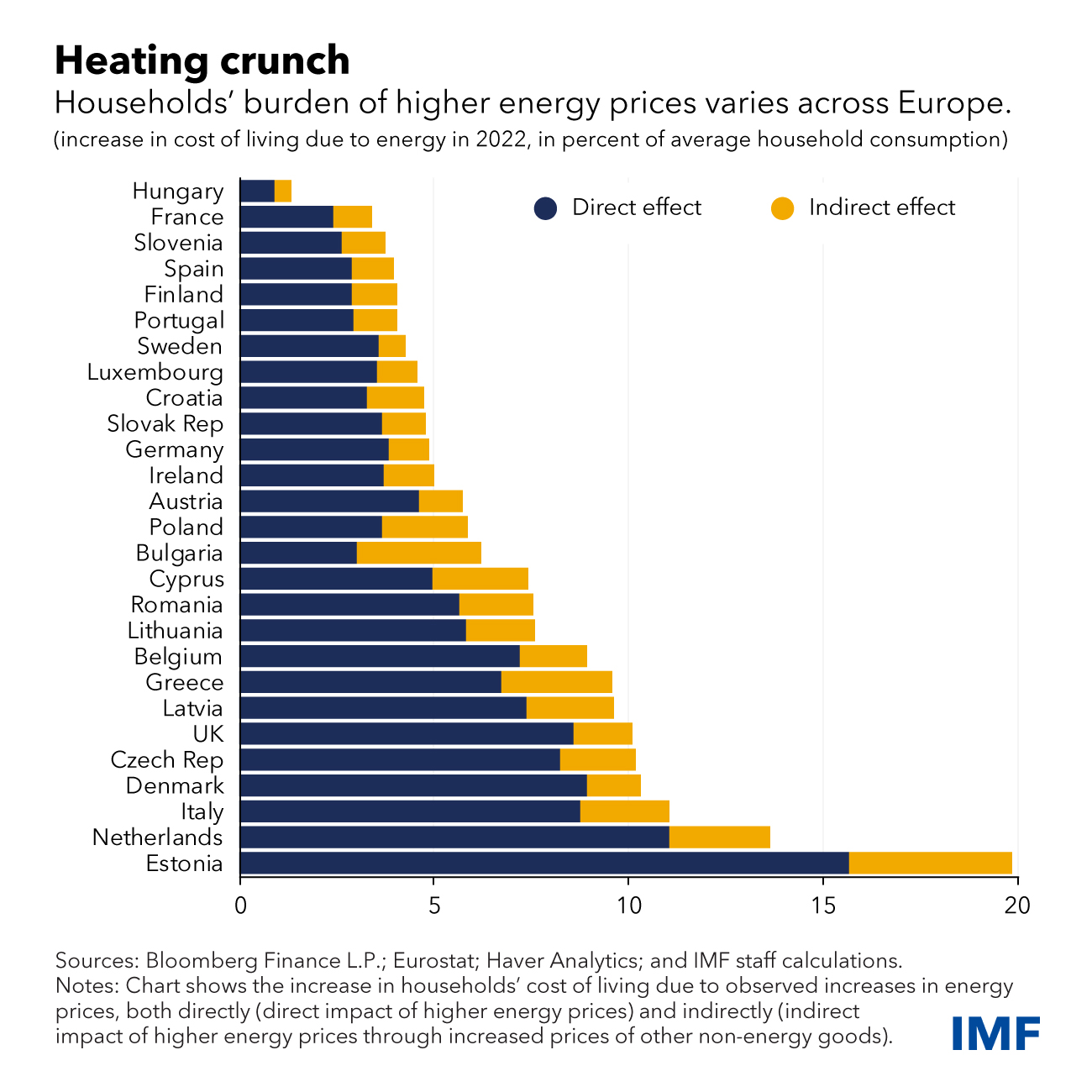

But fiscal policy also needs to help mitigate the brutal impact of higher energy prices on people and viable firms. This suggests that the pace of consolidation may have to be slowed for a few months. Higher energy prices have increased European households’ cost of living by some 7 percent on average this year despite the widespread measures taken to ease this burden.

Going forward, it will be important to keep energy-related support temporary to contain fiscal costs, and to maintain the price signals that will foster energy savings. Compared with price interventions, a better option is to support low- and middle-income households through lump-sum rebates on their energy bills. A close alternative is to combine general lump-sum discounts with additional support for the poor through the welfare system, financed by higher taxes for high-income households. Yet another, less efficient alternative is to implement higher tariffs for higher levels of energy consumption; while such an approach is not fully targeted to the vulnerable, it is still a better option than broad price caps.

Finally, steady implementation of reforms that enhance productivity, relieve supply constraints in energy and labor markets, and expand economic capacity remain essential to raise growth and ease price pressures over the medium-term. This includes accelerating the implementation of the 800-billion-euro economic recovery package, the Next Generation EU programs.

Strength, coordination and solidarity pulled Europe out of the COVID-19 crisis. Once again, the task ahead is immense, but if European policymakers muster the spirit of the pandemic response, it can be accomplished.