Since the COVID-19 outbreak was first reported in Wuhan, China in late December 2019, the disease has spread to more than 200 countries and territories. In the absence of a vaccine or effective treatment, governments worldwide have responded by implementing unprecedented containment and mitigation measures—the Great Lockdown. This in turn has resulted in large short-term economic losses, and a decline in global economic activity not seen since the Great Depression. Did it work?

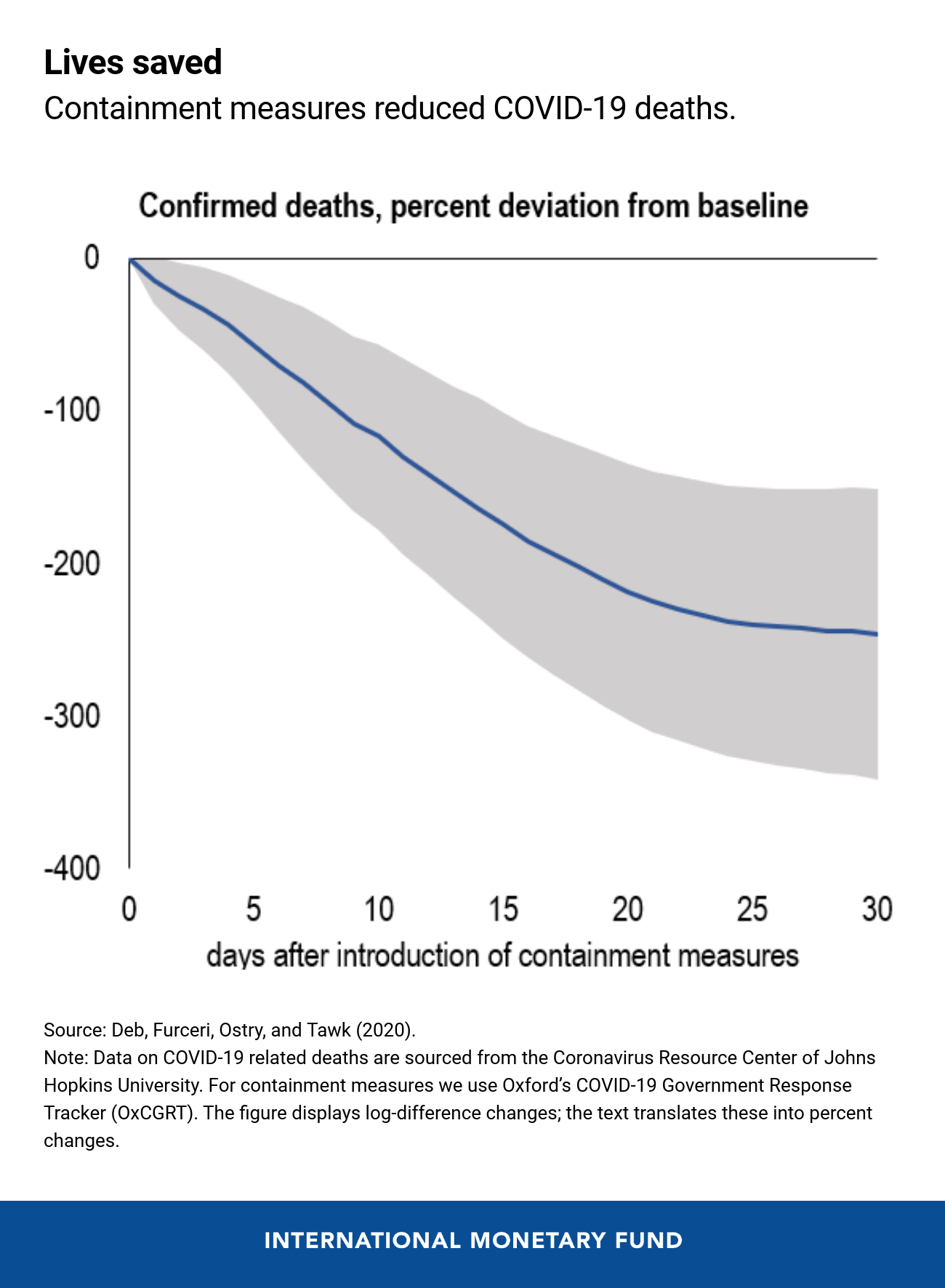

The Great Lockdown, despite its enormous short-term economic costs, has saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Our analysis, based on a global sample, suggests that containment measures, by reducing mobility, have been very effective in flattening the “pandemic curve.” For example, the stringent containment measures put in place in New Zealand—restrictions on gatherings and public events implemented when cases were in single digits, followed by school and workplace closings as well as stay-at-home orders just a few days later—are likely to have reduced the number of fatalities by over 90 percent relative to a baseline with no containment measures. In other words, the results suggest that, in a country like New Zealand, the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths would have been at least ten times larger than in the absence of stringent containment measures.

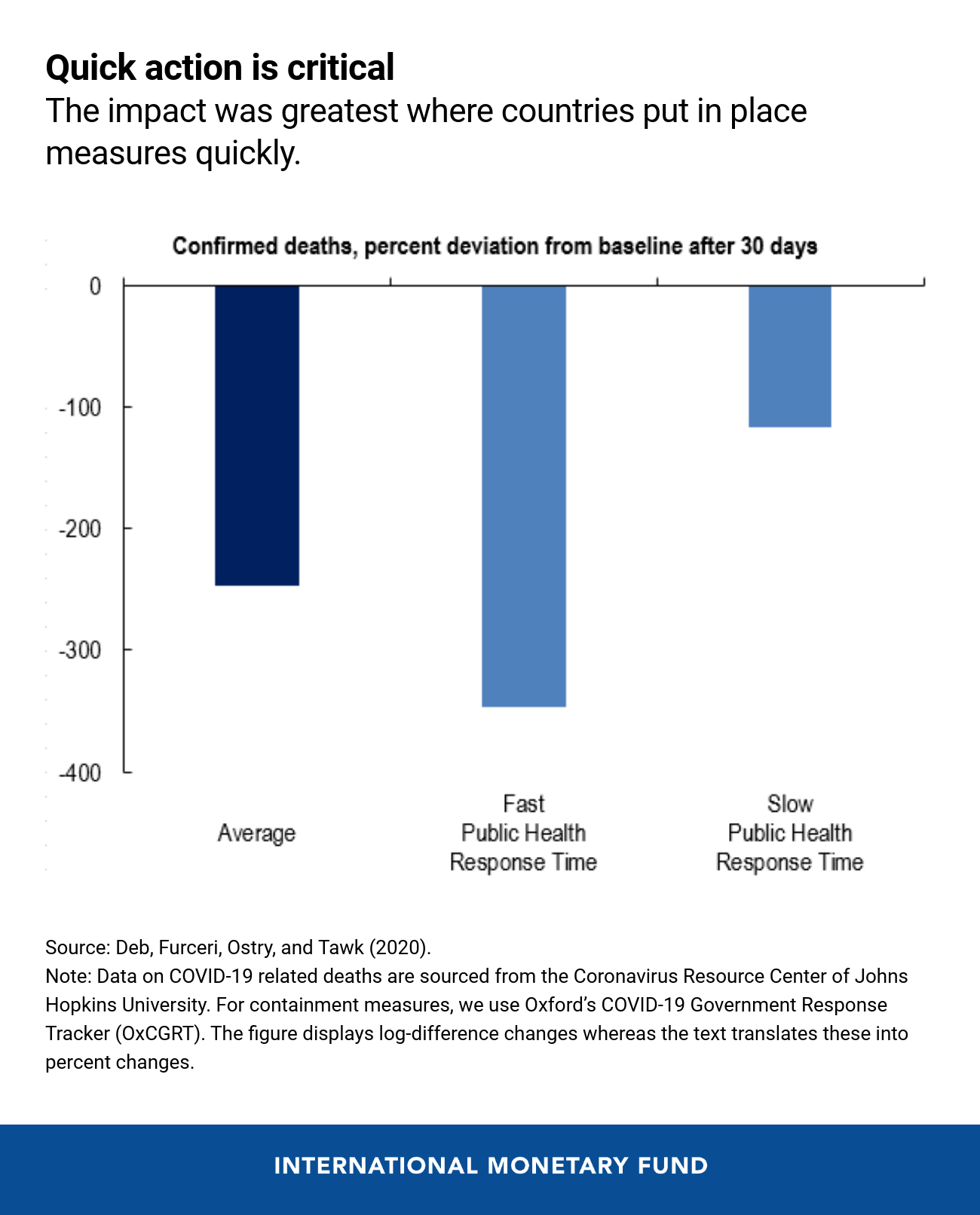

Early intervention and containment measured as the number of days it took a country to implement containment measures after a significant outbreak—public health response time in epidemiology lingo—played a significant role in flattening the curve. Countries such as Vietnam that were faster to put in place containment measures witnessed a reduction in the average number of infections and deaths of 95 and 98 percent respectively. This in turn has laid the foundation for growth in the medium term.

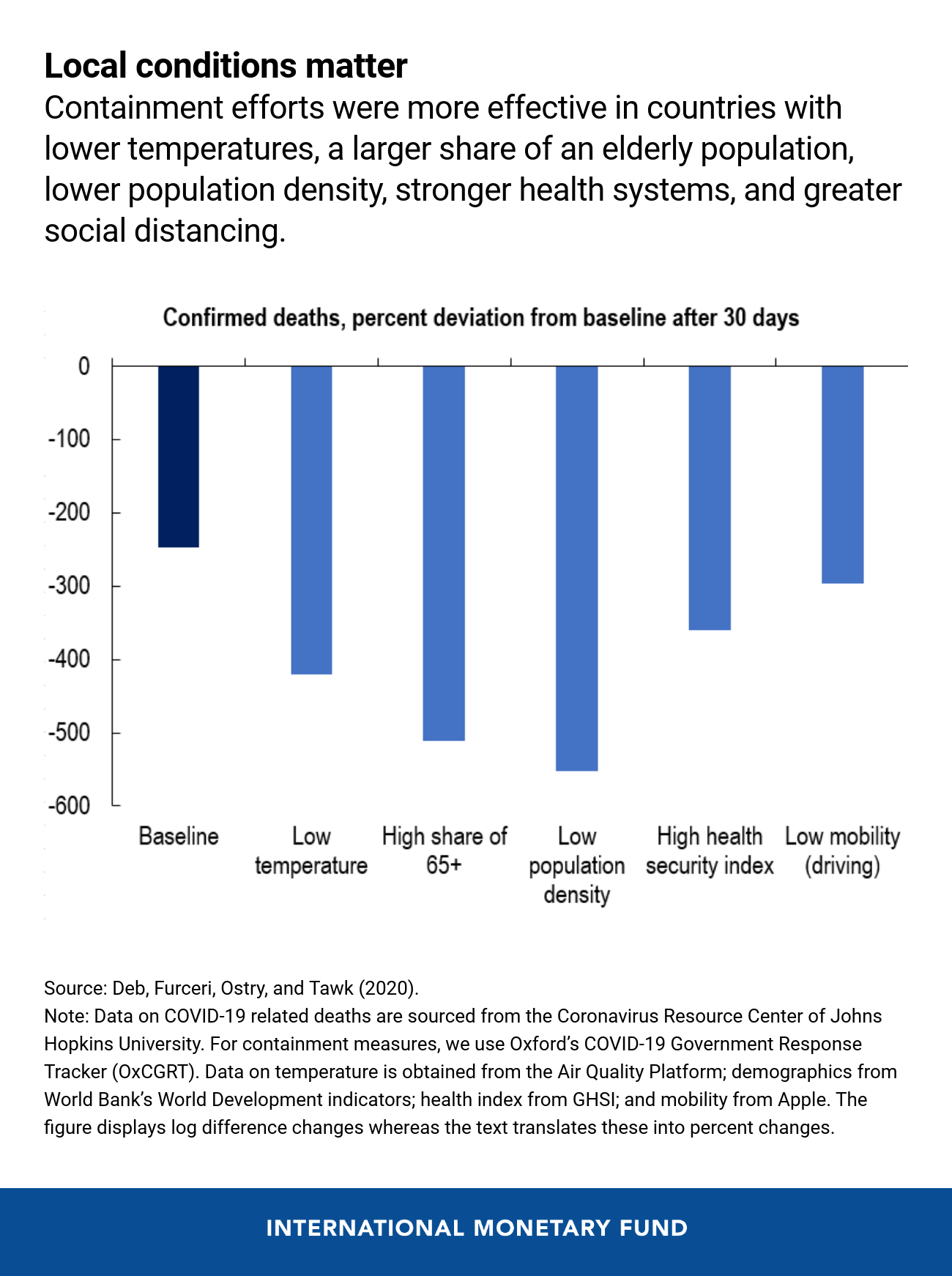

The effect of containment measures also varied depending on variations in country and social characteristics. The impacts were stronger in countries where colder weather during the outbreak produced higher infection rates, and where the population was older and hence more vulnerable to infection. On the other hand, having a strong health system and lower population density enhanced the effectiveness of containment and mitigation strategies by making them easier to implement and enforce. How civil society responded to de jure restrictions mattered as well. Countries where lockdown measures resulted in less mobility, and therefore more social distancing, saw a greater reduction in the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths.

Finally, we explored whether the effect of containment varies across types of measure. Many of these measures were introduced simultaneously as part of the country’s response to limit the spread of the virus, making it challenging to identify the most effective measure. Nevertheless, our results suggest that while all measures have contributed to significantly reduce the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, stay-at-home orders appear to have been relatively more effective.

Our empirical estimates provide a reasonable assessment of the causal effect of containment policies on infections and deaths, giving us comfort that the Great Lockdown, despite its enormous short-term economic costs, has saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Ultimately, the course of the global health crisis and the fate of the global economy are inseparably intertwined—fighting the pandemic is a necessity for the economy to rebound.