The pandemic, coupled with trade disruptions and Russia’s war on Ukraine, caused lasting harm to Asia-Pacific economies, damaging growth, productivity, and investment.

Specifically, it left deep and long-lasting scars which, without swift and

bold policy action, could restrain growth well into the future.

Our recent research

shows Asia is likely to experience the biggest output loss from the

pandemic of all five major world regions.

Scarring to Asian economies

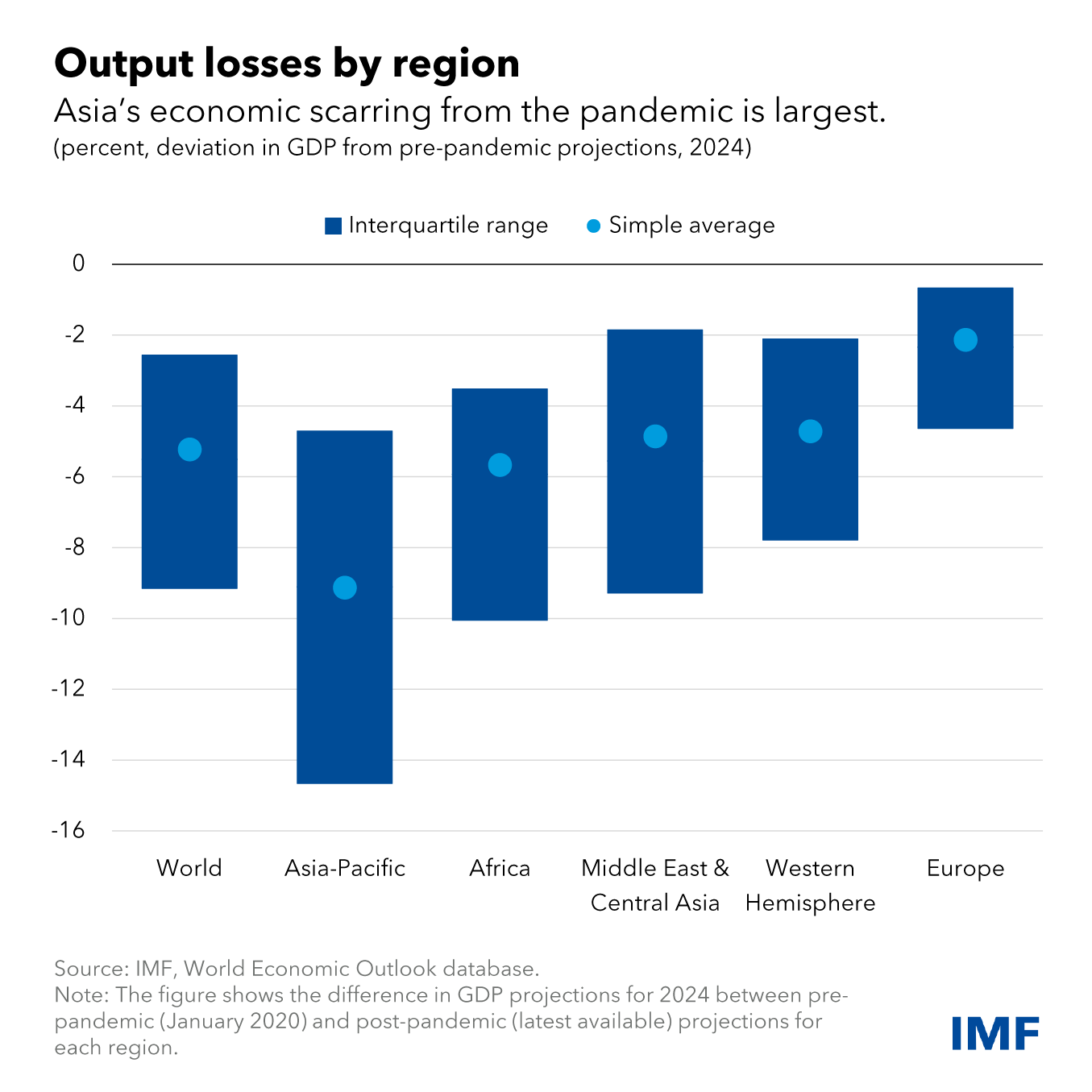

We measure the magnitude of these medium-term output losses by comparing 2022 forecasts of growth to projections for the same period made in January 2020. For Asia, we expect an average gross domestic product loss of 9.1 percent through next year, with greater losses for the region’s emerging and developing economies.

To explain Asia’s deeper and more persistent scarring, we examine three critical factors: investment, employment, and productivity growth.

Investment losses are an important contributor to scarring in Asia: a quarter of the region’s expected output losses result from reduced spending on investment projects. The effects are especially large in emerging economies, where we expect investment as a share of GDP to be 3 percentage points lower next year versus pre-pandemic projections.

One likely cause for this steep drop is Asia’s high corporate debt.

Businesses that borrow more are less likely to be able to expand or further

invest, as this would add servicing costs to existing obligations. That

would reduce overall capital spending, in turn reducing growth. This

dynamic is important in the context of historically high corporate debt in

Asia, which increased further during the pandemic, and is especially

elevated in emerging economies compared to other regions.

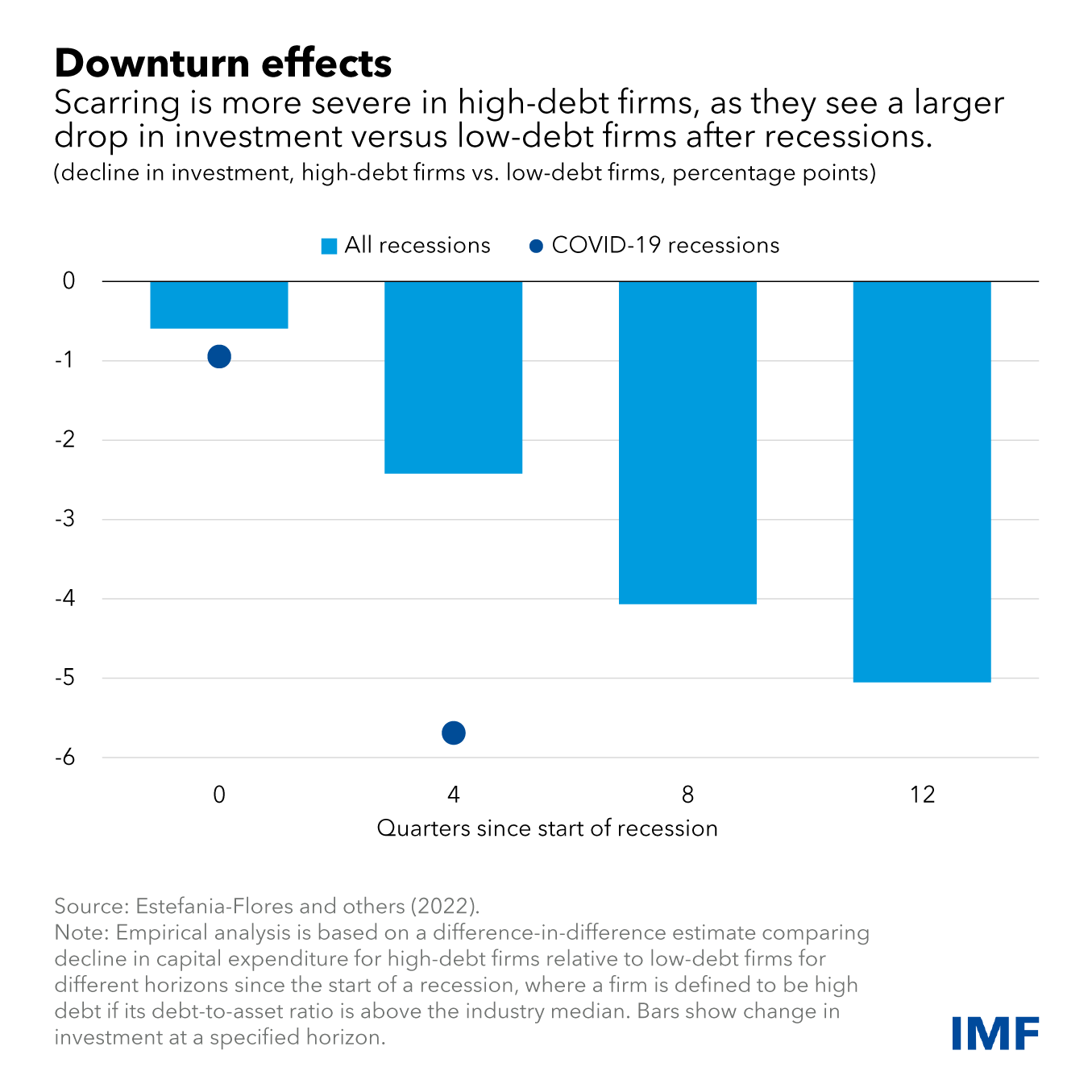

Using a new, detailed database of corporate balance sheets to estimate the effects of debt on investment, our research suggests that while recessions leave a large and persistent negative effect on firm-level investment, the effect is greater for those with high debt. Highly indebted firms, on average, see investment fall by 6 percent more than low-debt firms three years after a recession.

Greater borrowing alone accounts for at least 28 percent of the average drop in investment after recessions. Of these, smaller and less profitable firms with high debt tend to see the biggest investment declines. This reflects their difficulty securing external funding without collateral, as well as the limited internal funds these firms need to finance investment.

For employment, our calculations suggest that lower job growth would contribute about 2 percentage points to output losses in Asia. Employment could remain depressed for many years because of both the long-term loss of labor force quality and the reduced quantity of workers.

Regarding labor force quality, protracted school closures have caused severe learning losses among students, with classrooms closed longest in Asia’s low-income economies. We expect these education losses to significantly hamper the acquisition of valuable skills, leading to lower human capital than would have been without school closures and hence lower long-term productivity.

Regarding labor force quantity, we expect the COVID crisis to reduce the number of people entering the workforce, as evidence shows that pandemics can reduce fertility rates: epidemics over the past two decades, though smaller in scale, led to persistent declines in fertility rates of about 2.5 percent.

Mitigation policies

To mitigate scarring, economic reforms are essential to reduce corporate debt, boost labor outcomes, and raise productivity:

First, an orderly reduction of corporate sector debt should be prioritized, to improve resilience to future shocks. Reforms to the insolvency framework can also allow a reallocation of resources to more productive firms.

In addition, losses from school closures must be recouped: governments should assess learning setbacks and invest in teaching marketable skills to students. This may require more in-person training or longer school years, but retraining and other programs that can return people to the workforce would deliver economic benefits.

Another priority is to boost slowing productivity growth, which accounts for about half of Asia’s scarring. Here, digitalization can be essential, especially after the pandemic, as companies and industries harnessing digital technology can better connect with customers and employees, and as remote work and online sales protect workers, students, and businesses.

Empirical evidence from before and during the pandemic confirms how digitalization is building resilience and limiting scarring. Pre-pandemic data show that firms in more digital-oriented industries see a smaller decline in revenues following a recession than other firms.

During the pandemic, labor markets also favored digital sectors: high-frequency data from job sites like Indeed and LinkedIn shows that digital jobs remained robust and recovered more quickly, even in emerging economies.

Promoting digitalization is especially important in emerging economies, which have generally lagged advanced economies when it comes to online commerce, patents, and other digital innovation.

Conclusions

Asia could suffer significant long-term output losses from COVID-19, given diminished investment, productivity growth, and labor force participation. Economic reforms are essential to mitigate this scarring.

Asia should prioritize addressing the investment scarring from high corporate debt by promoting deleveraging, and mitigating education losses.

Finally, digitalization can help mitigate scarring and boost productivity growth. Though Asia has invested rapidly in this, more can be done. Enhancing digital connectivity should be a priority, especially in low-income developing countries, and for disadvantaged groups and regions.

With a bold, concerted push, economies in the region can return to growth and better protect themselves against future shocks.