The lingering pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are dealing a setback to the global economy. This is affecting trade, commodity prices, and financial flows, all of which are changing current account deficits and surpluses.

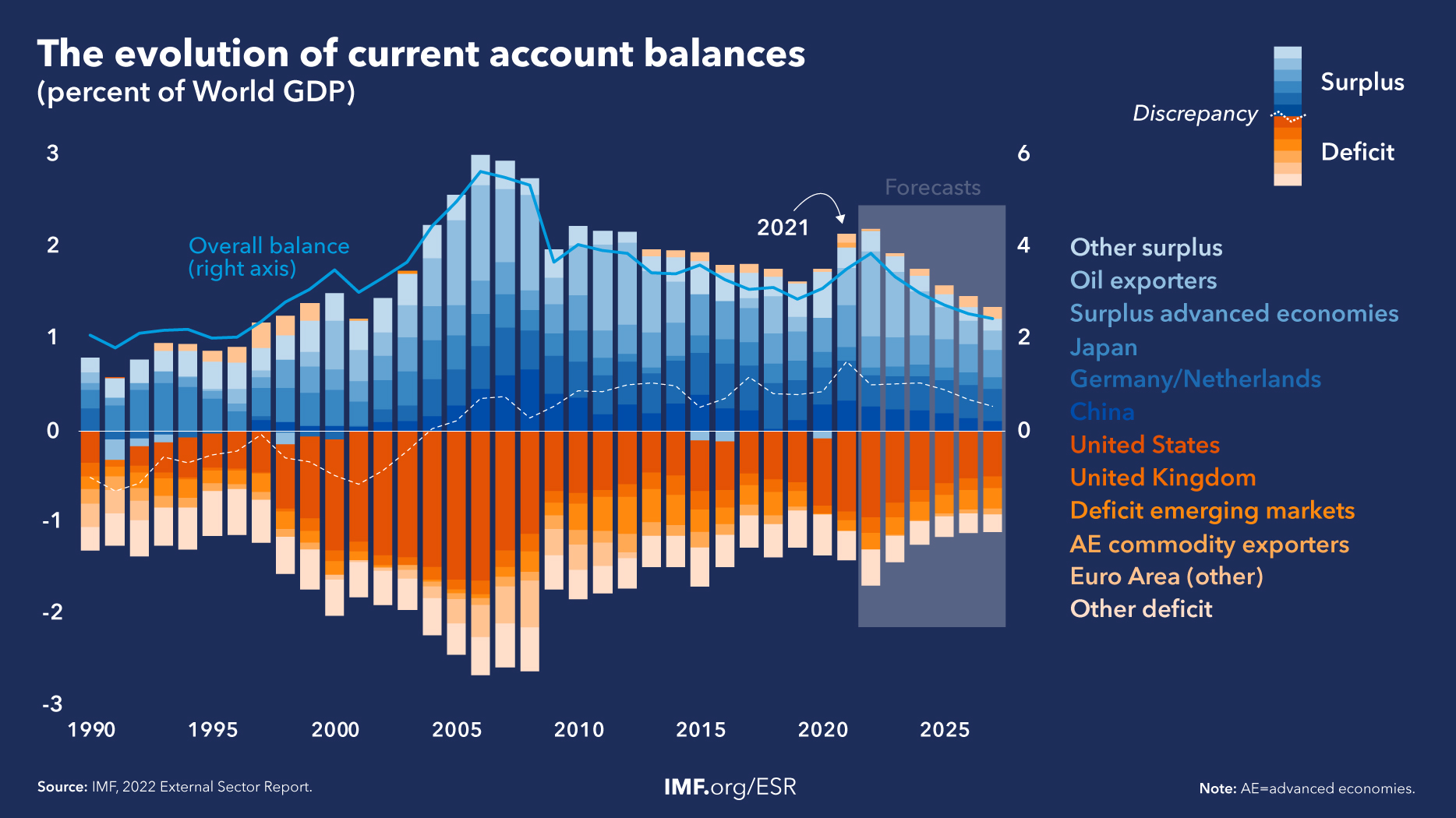

Global current account balances—the overall size of deficits and surpluses across countries—are widening for a second straight year, according to our latest External Sector Report. After years of narrowing, balances widened to 3 percent of global gross domestic product in 2020, grew further to 3.5 percent last year, and are expected to expand again this year.

Larger current account balances aren’t necessarily negative on their own. But global excess balances—the portion not justified by differences in countries’ economic fundamentals, such as demographics, income level and growth potential, and desirable policy settings, using the Fund’s revised methodology—could fuel trade tensions and protectionist measures. That would be a setback for the push for greater international economic cooperation and could also increase the risk of disruptive currency and capital flow movements.

Pandemic effects in 2021

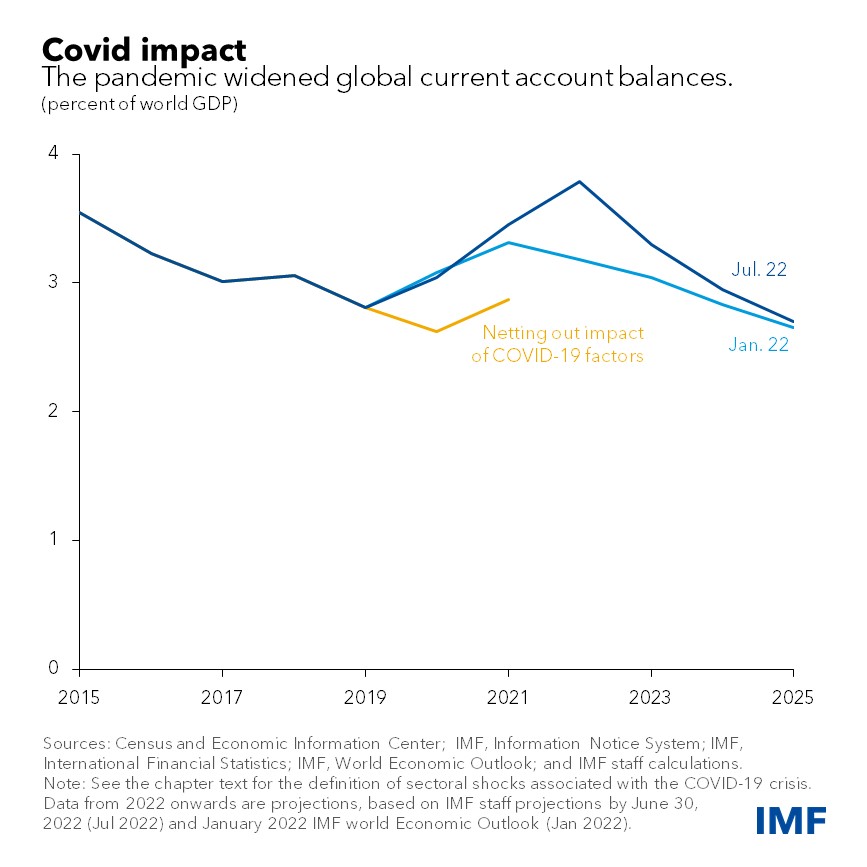

The pandemic widened global current account balances, and it’s still having an asymmetric impact on countries depending, for example, on whether they are exporters or importers of tourism and medical goods.

The pandemic and associated lockdowns also shifted consumption to goods from services as people reduced travel and entertainment. This also widened global balances as advanced economies with deficits increased goods imports from emerging market economies with surpluses. In 2021, we estimate that this shift increased the United States deficit by 0.4 percent of gross domestic product and contributed to an increase of 0.3 percent of GDP in China’s surplus.

Surplus economies like China saw also increases due to greater shipments of medical goods that often flowed to the United States and other deficit economies. Surging transportation costs also contributed to widening global balances in 2021.

War and tightening in 2022

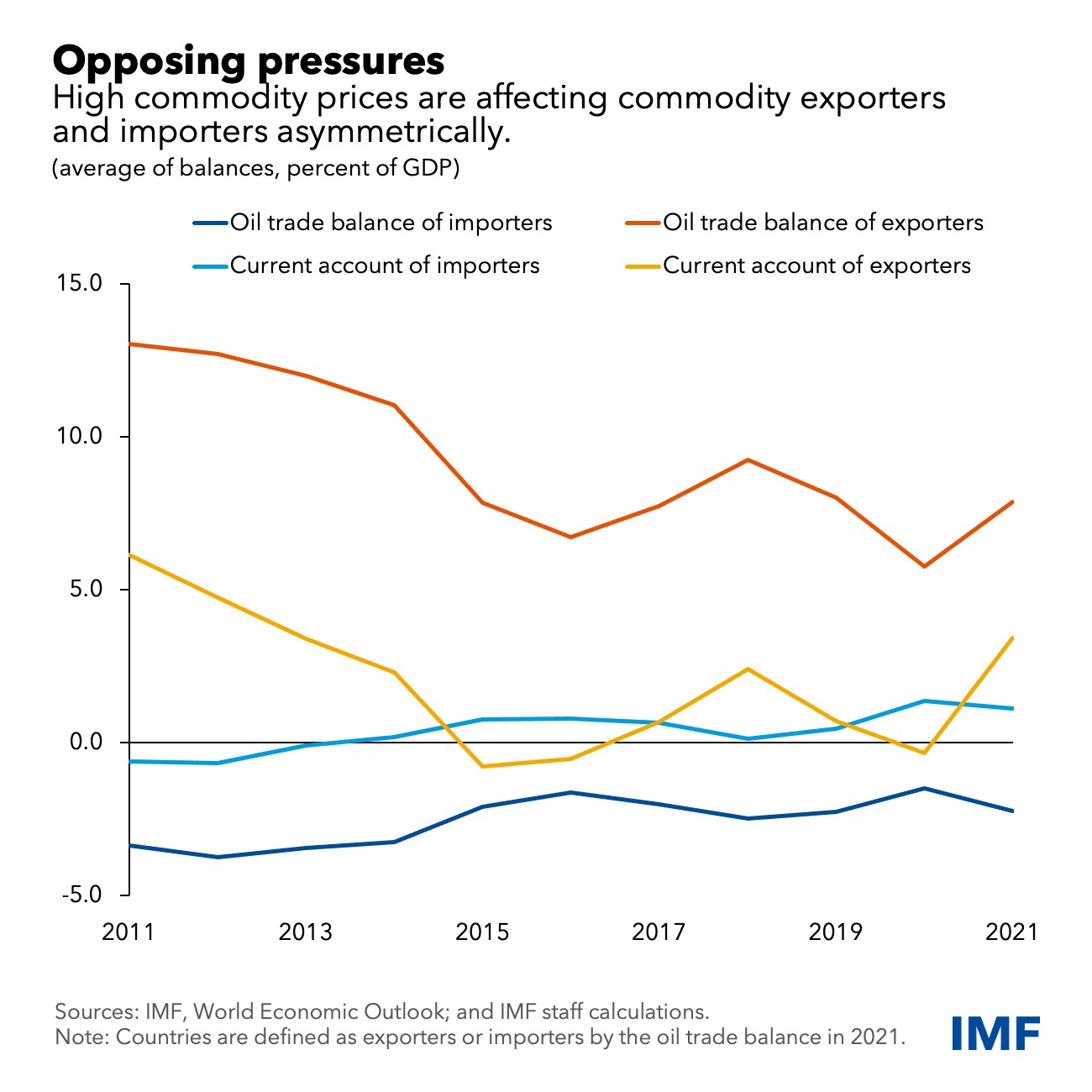

Commodity prices are one of the biggest drivers of external positions, and last year’s rally in oil prices from pandemic lows affected exporters and importers asymmetrically. Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine exacerbated the surge in energy, food, and other commodity prices, widening global current account balances by raising surpluses for commodity exporters.

Monetary policy tightening is driving currency movements as rising inflation is leading many central banks to accelerate the withdrawal of monetary stimulus. Revised expectations about the pace of the US monetary tightening brought about sizable currency realignment this year, contributing to the projected widening of balances.

Capital flows to emerging markets were disrupted so far in 2022 by increased risk aversion triggered by the war, with further outflows amid changing expectations about the increased pace of monetary tightening in advanced economies. Cumulative outflows from emerging markets have been very large, about $50 billion, with a magnitude that’s similar to outflows during March 2020 but a pace that’s slower.

Our outlook for next year and beyond is for a steady decline of global current account balances as pandemic and war impacts moderate, though this expectation is subject to considerable uncertainty. Global current account balances could continue to widen should fiscal consolidation in current account deficit countries take longer than expected. Moreover, the stronger dollar could widen the US current account deficit and increase global current account balances.

Other factors that could widen these balances include a prolonged war that keeps commodity prices elevated for longer, the varying degrees of central bank interest-rate increases, and greater geopolitical tension causing economic fragmentation, disrupting supply chains, and potentially triggering a reorganization of the international monetary system.

A more fragmented trade system could either increase or decrease global balances, depending on how trade blocs are reconfigured. Either way, though, it would reduce technology transfers, and decrease the potential for export-led growth in low-income countries and thus unambiguously erode welfare gains from globalization.

Policy priorities

The war in Ukraine has exacerbated existing trade-offs for policymakers, including between fighting inflation and safeguarding economic recovery and between providing support to those affected and rebuilding fiscal buffers. Multilateral cooperation is key in dealing with the policy challenges generated by the pandemic and the war, including to tackle the humanitarian crisis.

Policies to promote external rebalancing differ based on individual economies’ positions and needs. For economies with larger-than-warranted current account deficits that reflect large fiscal shortfalls, such as the United States, it’s critical to reduce government deficits with a combination of higher revenue and lower spending.

Rebalancing is a different proposition for countries with excessive surpluses, such as Germany and the Netherlands, which can be reduced by intensifying reforms that encourage public and private investment and discourage excessive private saving, including by expanding social safety nets in some emerging markets.