As the world gears up to avoid a climate catastrophe by limiting global warming to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius, more countries are putting carbon pricing at the center of their mitigation strategies.

Yet designing ways to put a price on carbon can be complicated and countries face multiple choices.

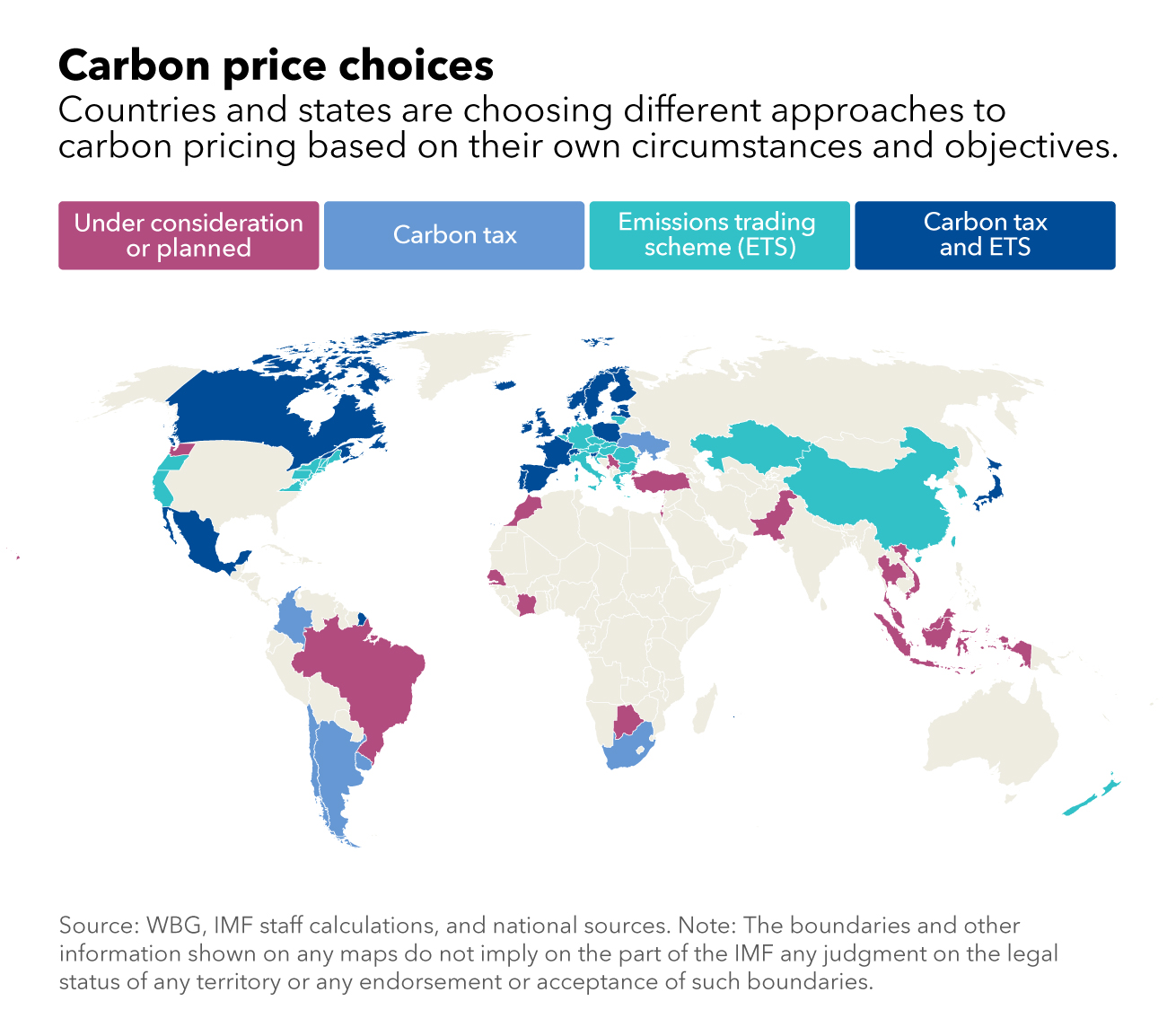

The Chart of the Week shows the expansion of carbon pricing schemes. So far, 46 countries are pricing emissions through carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes (ETS) and others are considering it.

Globally, ETSs and carbon taxes cover 30 percent of emissions, with prices rising as high as $90 per ton (in the European Union).

Despite the proliferation of carbon pricing schemes, policymakers should do more. To limit global warming, coverage must expand while prices rise from a global average of $6 per ton of CO2 today to $75 by 2030.

Policymakers considering introducing or scaling up carbon pricing face multiple decisions when choosing among and within policy instruments, as we explain in an IMF Staff Climate Note. These include ease of implementation, price levels, competitiveness concerns, alignment with other mitigation instruments, and coordination across countries. Countries may choose different approaches based on their own circumstances and objectives.

Taxes and trading schemes

A key choice is between carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes. Carbon taxes have practical appeal as they provide certainty over future emissions prices, helping encourage green investments and energy conservation. They can also be very simple to implement by tweaking existing fuel taxes and provide revenues that finance ministries can use to assist the poor, cut other taxes, or boost productive investments. Carbon taxes could also be extended to broader emissions sources, for example, methane emissions from extractive industries and, in some cases, agriculture.

Emissions trading schemes have appeal if policymakers prefer certainty over future emission levels. These schemes can be designed to mimic some of the advantages of taxes, including through price floors and allowance auctions (though allocating some allowances initially for free may garner support from affected firms). But given their significant complexity in design, implementation, and administration, many countries will find it challenging to develop ETSs.

Despite these differences, the two approaches have much in common. Both operate on the “polluter pays” principle, which efficiently encourages switching to more sustainable sources of energy and reducing emissions-intensive activities. Under both approaches, it’s vital to ensure that the rise in carbon prices needed to tackle climate change is acceptable politically. Carbon pricing reforms can protect the poor while supporting economic growth, for example by using some of the revenues to compensate vulnerable households and the remainder for labor tax cuts or productive investments.

With careful design, implementation and coordination, the economic costs of carbon pricing can be manageable—indeed for some countries these costs are more than offset by domestic environmental co-benefits (such as fewer deaths from local air pollution) even before counting the global climate benefits. Carbon pricing, in one form or another, is likely to be an essential element of mitigation strategies as the world transitions to net zero over the next three decades.

—The chart for this blog, originally published July 21, 2022, has been updated to reflect Indonesia's status as under consideration or planned.