(Versions in عربي, Español, 日本語, 中文, Français, and Русский)

House prices are inching up. But is this a cause for much cheer? Or are we watching the same movie again? Recall how after a decade-long boom, house prices started to fall in 2006, first in the United States and then elsewhere, contributing to the 2008-9 global financial crisis. In fact, our research indicates that boom-bust patterns in house prices preceded more than two-thirds of the recent 50 systemic banking crises.

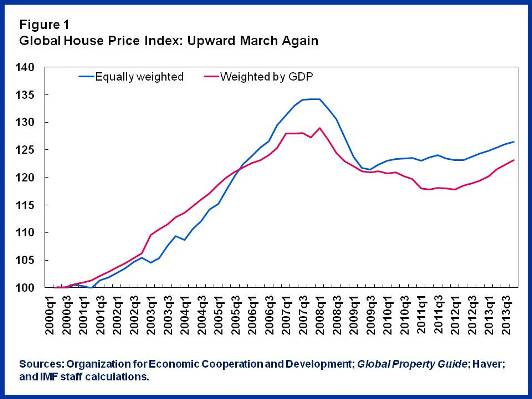

While a recovery in the housing market (Figure 1) is surely a welcome development, we need to guard against another unsustainable boom. Housing is an essential sector of every country’s economy and has systemic implications, which is why we at the IMF are focusing on it not only in individual countries but on a cross-country basis.

But the task is difficult for a couple of reasons. First, assessing when house prices are out of line with economic fundamentals is as much art as science. Second, the policy toolkit to manage housing cycles is still under construction.

To share cross-country information, analysis on housing markets, and discussions on the effectiveness of policy response, the IMF has launched a webpage—the Global House Price Watch—that will provide a one-stop shop for our data on housing indicators. This information will be updated regularly, including in the form of a quarterly update to be released in July.

The IMF also held a conference last November, co-organized with the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, bringing together experts on the housing sector, and a second conference, where I delivered a speech, was held last week, hosted by the Bundesbank.

Determining a fair price

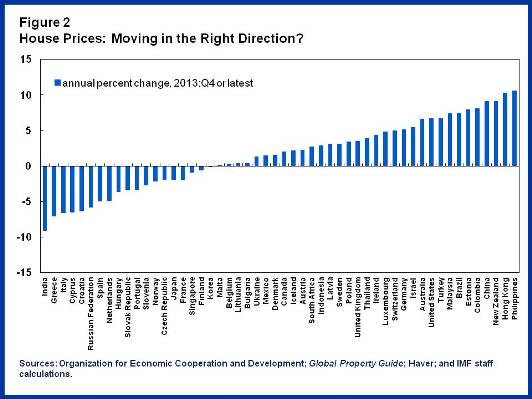

Over the past year, 33 out of 52 countries in our Global House Price Index showed increases in house prices (Figure 2). Are these changes moving house prices closer to or further away from economic fundamentals?

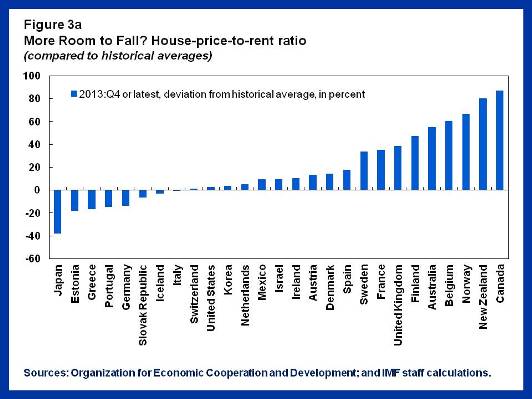

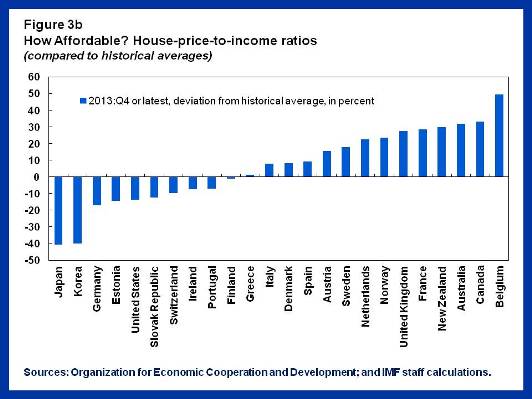

Theory asserts that house prices, rents, and incomes should move in tandem over the long run. If house prices and rents get way out of line, people would switch between buying and renting, eventually bringing the two in alignment. Similarly, in the long run, the price of houses cannot stray too far from people’s ability to afford them––that is, from their income. The ratios of house prices to rents and incomes are thus often used as an initial check on whether house prices are out of line with economic fundamentals.

What does the evidence show? For the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, where a sufficiently long time-series of house prices, rents and incomes is available, these ratios remain well above the historical averages for a majority of countries. This is true for instance for Australia, Belgium, Canada, Norway and Sweden (Figures 3a and 3b).

Detecting overvaluation more art than science

The evidence on house price-to-rent and house price-to-income ratios, however, provides only a broad indication of housing market valuations. Judgments about housing valuation also require supplementary information, such as credit growth, household indebtedness, lender characteristics, and the method of financing.

As part of its regular reports on economic conditions in countries—the so-called Article IV reports—IMF country teams often provide an assessment of housing markets, and are increasingly paying attention to credit growth, along with several other country-specific features of the housing market. In some cases, this more detailed look suggests much more modest overvaluation than indicated by the house price to income and house price to rent ratios. One example of this is Belgium, where the IMF concluded that despite the high valuation ratios, risks of a sharp correction of real estate prices appear contained. These country-specific factors for housing cycles suggest that the policy response cannot be ‘one size fits all’.

Constructing a policy toolkit

Regulation of the housing sector involves a complex set of policies—the noted economist Avinash Dixit suggested the acronyms MiP, MaP, MoP to refer to microprudential, macroprudential and monetary policy, respectively.

Microprudential policy aims to ensure the resilience of individual financial institutions. It is necessary for a sound financial system but may not be sufficient; sometimes, actions suitable at the level of individual institutions can destabilize the system as a whole.

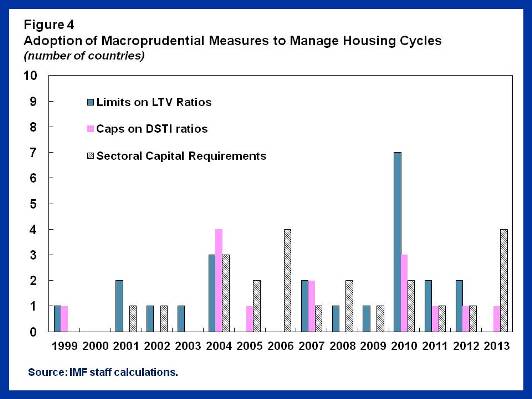

Hence we also need macroprudential policies aimed at increasing the resilience of the system as a whole. The main macroprudential tools used to contain housing booms are limits on loan-to-value (LTV) ratios and debt-to-income (DTI) ratios and sectoral capital requirements (Figure 4). Hong Kong SAR has imposed caps on loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios since 1990s, Korea since 2000s, and during and after the global financial crisis, over 20 advanced and emerging economies have followed their example.

Another macroprudential tool is to impose stricter capital requirements on loans to a specific sector such as real estate. This forces banks to hold more capital against these loans, discouraging heavy exposure to the sector. In many advanced economies—Ireland, Norway, and Spain— and emerging market economies— Estonia, Peru, and Thailand— capital adequacy risk weights were increased on mortgage loans with high loan to value ratios.

Though evidence thus far suggests that macroprudential policies are effective in the short-run in cooling off housing markets, it is clear that honing them remains a work-in-progress.

Finally, there is the monetary policy, which involves the central bank raising interest rates if they want to cool off the housing sector. While monetary policy could be an important tool in many cases in support of macroprudential policies, the optimal allocation of responsibilities between prudential policy and monetary policy remains a matter of much discussion. What is clear however, is that monetary policy will need to be more concerned than it was before with financial stability and hence with housing markets.

The tools for containing housing booms are still being developed. The evidence on their effectiveness is only just starting to accumulate. The interactions of various policy tools can be complex. But all this should not be an excuse for inaction. The interlocking use of multiple tools might overcome the shortcomings of any single policy tool. We need to move from “benign neglect” to an “all of the above” approach when it comes to policy choices.