False Profits

Finance & Development, September 2017, Vol. 54, No. 3

Avoidance by multinationals and competition between governments are forcing a rethink of the international tax system

The League of Nations did not have a Facebook page. Its staff didn’t Google or order online from Amazon. A century ago foreign direct investment involved tangible things like railways and oil wells. Royalties meant charges on coal and the like, not payment for the use of brand names or patents. Multinational enterprises did not dominate world trade.

Things have changed. The international economy has seen the rise of multinationals and the growth of trade in services and global capital flows. Intangible assets such as patents and telecom licenses have become central to modern business, and digital technology offers opportunities to do business in a country with little if any physical presence there. These changes raise tax issues unimaginable in the 1920s. Yet the framework established by the League of Nations still dominates how we tax multinationals.

The stresses placed on that framework have increased over the last decades, bringing it close to the breaking point—perhaps beyond.

Two problems—distinct but related—are at the heart of those stresses. One is tax avoidance by multinationals: the use of legal ways to shift profits from where they will be taxed at a high rate to where they will be taxed at a low one. The other is “tax competition” between governments: the use of low rates or other favorable tax provisions to make themselves more attractive for real investment and less vulnerable to avoidance activities that shift paper profits abroad (making other countries correspondingly less attractive and more vulnerable).

A quick guide

International taxation is horrendously complicated (a serious problem in itself). Here is a quick account of how the system for taxing multinationals works.

At the heart of how countries determine the taxable profits of companies within a multinational group is the principle of “arm’s length pricing.” This means calculating the profits earned by each such company by valuing any transaction it has with other companies in that multinational group by using prices at which unrelated parties would have undertaken that transaction. Each country then taxes the profits allocated in this way to any member of the group that is either legally established or has a clear and reasonably sustained physical presence there (in the jargon, a “permanent establishment”). This establishes the tax base in what is often called the “source” country.

At a second step, under “worldwide” taxation, the country in which the parent company is resident for tax purposes also taxes income earned by its affiliates abroad, though it will often give a credit for taxes paid there. This practice, however, has become rarer in recent years. It still applies in the United States, but (as in other countries using a worldwide system) tax is payable only when earnings are repatriated in the form of dividends. This is one reason US companies have more than $2 trillion in unrepatriated earnings. But many countries instead have “territorial” systems, meaning they effectively exempt business income earned abroad. So current arrangements for the taxation of business income across the world look much like a system of source-based taxation.

There has not been much conscious design in these arrangements. There is no World Tax Organization to forge and apply common rules (though World Trade Organization rules do constrain some aspects of tax policies). Countries often define aspects of their tax relations through bilateral tax treaties (more than 3,000 of them), and there are various guidelines for applying arm’s length pricing. These modest elements of multilateralism have been supplemented in the past few years by efforts to contain some of the most outlandish avoidance devices, through the G20/OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project (more on this below). But governments and multinationals still have plenty of room to maneuver. And many developing economies and civil society organizations see the current system as driven by the interests of the most advanced economies.

Games companies play

The arm’s length principle has a logical rationale. In theory, it subjects multinationals to the same tax treatment as a series of independent firms doing the same things. The trouble is that multinationals can exploit that principle by doing things that independent firms would have no reason to do.

One example can stand for many. Multinationals can try to manipulate the prices (“transfer prices”) at which they transact within the group to reduce their overall tax liability—setting artificially low transfer prices, for instance, for sales from affiliates in high-tax jurisdictions to those where taxes are low. The problem for the tax authorities is then to find or construct arm’s length prices at which to value these transactions. And that has become increasingly tough, as trade within multinationals has grown not only in volume but has come to center on hard-to-value items. One example is the sale to an affiliate in a low-tax jurisdiction of an as-yet-unexploited patent whose arm’s length value is unclear (though the company likely has a shrewder idea than the tax administration).

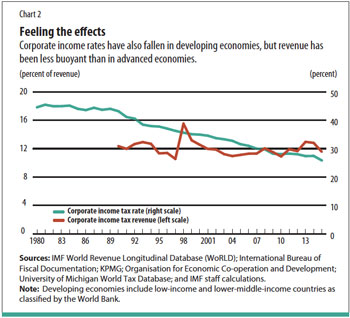

There is plenty of evidence that profit shifting is extensive. Estimates for the United States put the loss at between one-quarter and one-third of total corporate tax revenue in 2012 (Clausing 2016). Losses elsewhere may well be larger—and are of particular concern in developing economies, which get a higher proportion of their total revenue from corporate taxes and have fewer alternative revenue sources to fall back on.

The BEPS project has made progress in addressing many of the most egregious forms of tax avoidance. Covering 15 wide-ranging areas (such as limiting interest deductions and improving dispute resolution), it has delivered four minimum standards to which the G20 encourages all countries to commit. (One, for example, aims to limit abuse of tax treaty provisions.) Implementation of the project’s standards is now supported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s “Inclusive Framework,” to which over 100 countries belong.

The project does not change the fundamental structure of the international tax system. Even its strongest advocates have described it as firefighting. It remains to be seen whether the fires have caused damage that can be repaired and fixed with a lick of paint—or have left a fundamentally unsafe structure that, sooner or later, will have to be rebuilt.

Games governments play

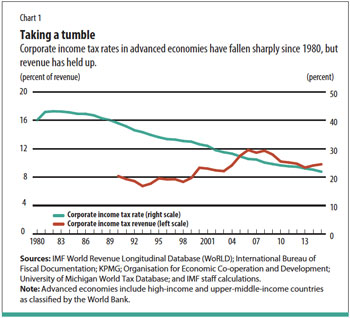

The most obvious sign of intense international tax competition is the rapid decline of corporate tax rates around the world (see Charts 1 and 2). Strikingly, revenues in advanced economies have on average held up, probably in large part because of an increasing share of capital in national incomes.

But it is not just headline rates that matter. Governments are adept at finding ways to manipulate many other aspects of their tax systems to attract real investment or paper profits rerouted by tax avoidance. Governments seemingly outraged by low effective payments often sound like Captain Renault in the movie Casablanca, claiming to be “shocked” by the discovery of gambling in Rick’s bar.

So what’s wrong with such competition between governments? There are those who indeed welcome tax competition as a way of limiting “wasteful” public spending. But even leaving aside the fact that “wasteful” is in the eye of the beholder, this “starve the beast” argument has been heard less often since the crisis of 2008, with many governments strapped for revenue. The central problem, in any case, is that tax competition is a particularly inefficient way to limit the tax take.

This is because self-seeking national tax policies spill over in harmful ways. If a country makes its tax system more attractive, it increases its tax base by attracting more real investment or inward profit shifting, which, from its national perspective, is a good thing. But, by the same token, the tax base in other countries is likely to go down—a bad thing for them. If each country sets its own tax policy ignoring the adverse effects on others, they will end up collectively worse off than if they had cooperated. What underlies this problem, ultimately, is the mobility of the tax base—with source-based taxation under the arm’s length principle being especially vulnerable, given the ease of shifting not only real investments but, through avoidance of various kinds, paper profits.

The BEPS project does not address the fundamental forces that drive tax competition. Its mantra has been to mend the 1920s system by establishing taxation “where value is created.” That sounds something like source taxation, which as just seen is especially prone to damaging competition. Moreover, while making avoidance harder limits one vulnerability, it may worsen the other. Governments tolerate or even encourage avoidance as a way by which firms that are especially able to move their activities or shift their profits abroad can reduce their tax bills. If clamping down on avoidance makes that harder, they may well use other tax devices to protect their tax base—for example, by further lowering tax rates.

What is to be done?

While the BEPS project is an impressive attempt to mend the international tax system, few if any see it as a fundamental solution. So reform remains on the agenda. Some proposals retain key concepts of the 1920s system. One, for instance, is to widen the notion of a “permanent establishment” to recognize that, in this digital age, companies can do considerable business in a country without having much of a physical presence there.

More fundamental changes are also being suggested. The European Commission, for instance, has revived a proposal to allocate a multinational’s profit across participating EU countries not by arm’s length pricing but by a mechanical formula, reflecting for instance the extent of its sales, assets, and employment in each country. The advantage of such “formula apportionment” is that it makes transfer prices between the participating countries irrelevant for tax purposes. It is not, however, immune from tax competition—governments would have an incentive to attract whatever is included in the formula so as to bring a larger share of the multinational’s profits into its tax base.

In the United States, the “destination-based cash flow tax,” which would exempt exports from taxation and tax imports, has received a lot of attention recently. If all countries adopted it, transfer prices would become irrelevant for tax purposes (because the prices attached to exports and imports have no impact on tax liability in any country). And because consumers generally don’t relocate in response to differences in rates of tax on consumption, this type of tax is much less vulnerable to erosion by international competition.

Even if one could conceive of an ideal alternative to the 1920s system, implementing it would raise difficult coordination problems. Overall, countries should gain from coordinating their approach to corporate taxation. But there is a problem: a group of countries that agrees to raise tax rates becomes more vulnerable to being undercut by others. That is, countries that coordinate can expect to gain from doing so, but those that stay outside stand to gain even more.

Still, competition itself could lead to an efficient form of coordination. One consequence of replacing a standard corporate tax with a destination-based cash flow tax, for example, is fewer profit-shifting problems for a country adopting it but more for everyone else. This is because setting a high price for exports from the country with a destination-based cash flow tax will not affect tax liability there (receipts from exports, remember, are then exempt). It will, however, reduce tax liability in countries retaining a traditional corporate tax (imports there being deductible against tax). And that would put great pressure on those others to adopt a destination-based cash flow tax too.

That brings us to a last but fundamental issue. Both formula apportionment and the destination-based cash flow tax would transform how tax revenue is allocated across countries. With a destination-based system, tax revenue accrues to the countries where final consumption takes place. That is quite different from the idea that it should accrue to the country of production. Resource-producing countries, for example, are unlikely to see such an allocation of revenue as acceptable. As with all tax issues, a key question in rethinking the international tax system is ultimately: Who should get the money?

Reference

Clausing, Kimberly A. 2016. “The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond.” National Tax Journal 69 (4): 905–34.