Beating Back Ebola

Finance & Development, June 2017, Vol. 54, No. 2

Mehmet Cangul, Carlo Sdralevich, and Inderjit Sian

Nimble action on the economic front was key to overcoming the health crisis

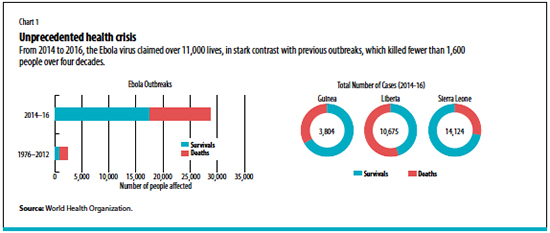

In March 2014, the largest Ebola virus disease outbreak in history presented West Africa and the international community with an unprecedented public health crisis. From late 2013 to early 2016, the disease claimed more than 11,000 lives and infected over 28,000 people (see Chart 1).

Ebola also caused an economic crisis, triggered by massive health and social spending and compounded by the almost simultaneous collapse in commodity prices. Already under strain before the epidemic hit, the health and social systems of the governments of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—the countries most affected by the epidemic—were overwhelmed.

Unprecedented epidemic

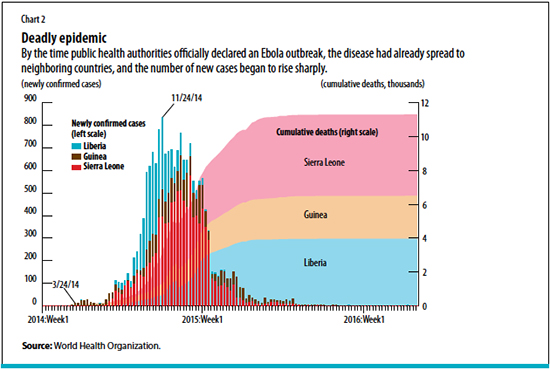

The world woke up slowly to the reality of the Ebola epidemic. While the first known patient was infected in December 2013 in Guinea, it was not until three months later that the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared an Ebola outbreak in the region. By then, the virus had already spread to neighboring Liberia and Sierra Leone as a result of porous borders and high population mobility in the region.

Ebola is a lethal infectious disease. The number of deaths started rising sharply, reaching more than 10,000 by the end of March 2015 (see Chart 2). The fatality rate was about 40 percent on average but was close to 70 percent in the initial phase of the epidemic.

With casualties rising, domestic authorities in the Ebola-stricken countries struggled to contain the virus’s spread. Constrained financial capacity to deliver emergency health care, confusion surrounding the transmission of the virus, and burial practices that spread the disease posed significant challenges for a region that had little experience dealing with public health disasters on such a scale.

In addition to the initial delays in diagnosing the epidemic, international health agencies were also grappling with ways to contain the disease, resulting in slower mobilization of international support than was warranted. The lack of a cure or vaccine further complicated containment. And concerns about a pan-African epidemic or even a global pandemic grew only after cases emerged in Nigeria, Senegal, and Mali and as far away as Europe and the United States.

Collapse in economic activity

As the epidemic spread, tourism collapsed in the region, foreign direct investment fell, and trade and services were severely reduced, especially in densely concentrated urban areas. While agricultural production—largely for domestic consumption—was less affected, the trade of agricultural goods was stifled by wide-scale quarantine measures. Entire villages and communities were sealed off, sometimes for months, to isolate and limit the transmission of the disease, which proved extremely resilient to human efforts to contain it.

These measures dramatically increased food shortages. Two-thirds of households in Sierra Leone were reported to lack easy access to food in June 2015. Quarantines and the closure of borders between countries also led to a plunge in regional trade: potato exports from Guinea to Senegal fell more than 90 percent in the year ending in August 2014. At the same time, the collapse in demand, restrictions on the movement of goods and people, and the delay or cancellation of investment increased unemployment.

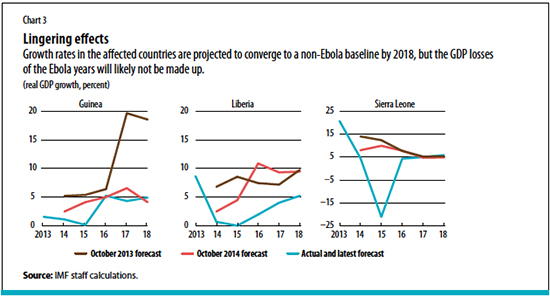

A collapse of global prices of commodities compounded the crisis in the three Ebola-stricken countries. GDP in Sierra Leone declined more than 20 percent in 2015. The fall in growth was less severe in Guinea and Liberia, where mineral production was relatively less affected. For all three countries, medium-term growth prospects deteriorated significantly (see Chart 3).

Because of the collapse of economic activity, the public finances of the three Ebola-stricken countries deteriorated abruptly. Government revenues in the three countries declined by almost 3 percentage points of GDP on average between 2013 and 2015, with Liberia accounting for the largest drop. At the same time, governments—under pressure to deliver emergency health care services and increase containment efforts—increased public spending by almost 5 percentage points of GDP over the same period. Liberia witnessed the largest increase, at more than 9 percentage points of GDP.

Rapid, flexible response

With the impact of the epidemic escalating, a coordinated global response and relief effort proved essential to stem the spread of the disease and limit the human suffering and economic deterioration in countries that were still recovering from war and political instability. The international community responded by focusing on addressing the health emergency and providing financial support, disbursing $5.9 billion in aid.

The immediate concern was providing rapid medical assistance to overwhelmed domestic health agencies. With a well-established presence in the region, Doctors Without Borders moved in March 2014 to set up isolation facilities and manage clinical care for the swelling number of Ebola patients. At the peak of its intervention, this nongovernmental organization employed nearly 4,000 national staff members and more than 325 external experts to combat the epidemic across the three countries. The WHO, in collaboration with Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network—a network of public health specialists, United Nations and international health agencies, and nongovernmental organizations—also responded to mobilize and deploy medical experts to support local clinics once the epidemic was officially declared.

Massive financial support also came through a number of channels. The United Nations set up the Ebola Response Multi-Partner Trust Fund to mobilize funding and provide a common financing mechanism. Over $166 million was raised from members, nongovernmental organizations, and private institutions. The WHO also received $459 million in donations from over 60 donors, including the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, the World Bank, and the African Development Bank.

The IMF was the first international financial institution to provide financing to the government budgets of the stricken countries. Within its mandate, it acted swiftly to provide the authorities with financial support, which was essential to sustain the delivery of key government services, including health care and education, while offering continuous policy advice. Because the fiscal pressures warranted a direct lifeline to government budgets, the IMF decided to finance government directly—rather than follow its usual approach of providing funds to central banks to prop up international reserves. The funds allowed the governments to spend on measures to stem the spread of the disease and protect critical social and infrastructure spending.

The IMF disbursed a total of $378 million in three phases beginning in September 2014, just as the epidemic started to gather pace. As the gravity of the situation became clear, and concerns about the potential impact on the economy increased, the institution went ahead with disbursing funds—even though the evidence on the economic consequences was not yet fully clear—judging that the risks of inaction were simply too high. This sum included almost $100 million in debt relief to Ebola-hit countries disbursed in March 2015, delivered through a new trust that had been quickly created to aid countries hit by public health disasters.

In June 2016, the WHO declared all three countries virus free and economic growth has started to strengthen in Guinea and Sierra Leone. Recovery has not yet occurred in Liberia, mainly due to the retrenchment of activity and investment in the natural resource sector.

Lessons learned

The initial delay in recognizing the gravity of the epidemic and taking appropriate action shows that the world was unprepared for the Ebola crisis. Lessons on how to strengthen health systems to be better prepared to address catastrophic epidemics, at both the national and the international level, are still unfolding. It is clear, though, that the health systems in these countries still need to be strengthened, with the support of the international community—especially given the region’s high susceptibility to infectious diseases due to the tropical climate. The epidemic also underlined the importance of early action plans and decentralized early warning systems to activate the health infrastructure and the global response in a timely way. Contingency planning and infrastructure investment—such as better sanitation facilities and basic health care structures—can also help prevent future crises.

From an economic perspective, the experience underscored the need for flexibility and speed in formulating a response. When government revenues fell, the right response was more spending to counteract the negative impact of the epidemic on the overall economy, despite the decline in revenues. But such policies to fight recession require rapid financing—and this is why it is so important for the international community to provide quick, massive, and coordinated financial support.

Although global coordination and support are necessary, success depends on the leadership of the affected countries themselves. In Liberia, the tide turned after President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf asked tribal chiefs to persuade their people to abandon traditional burial customs. Strong leadership also helped communicate the importance of safety measures and sanitary practices to change behavior and prevent the transmission of the virus. But in all three countries the resilience and adaptability of the people were the key factor in the success of the combined efforts of the national authorities and global community.

CARLO SDRALEVICH is an advisor and MEHMET CANGUL and INDERJIT SIAN are economists, all in the IMF’s African Department.