Risky Mix

Finance & Development, March 2017, Vol. 54, No. 1

Ralph Chami, Connel Fullenkamp, Thomas Cosimano, and Céline Rochon

If financial institutions combine banking and nonbanking business there is potential for danger

The biggest banks in the world are not just banks—they’re financial supermarkets that can underwrite securities, manage mutual funds, and act as brokers in addition to lending money. Offering many different kinds of financial services increases the profits of these institutions—whether they are universal banks, in which the functions are all part of the bank, or are holding companies that own separate bank and nonbank providers.

But when all these activities are under one roof, many regulators believe that new risks are added that could endanger both the institution and the financial system. After the global financial crisis of 2008, regulators in a number of countries proposed rules to insulate traditional banking (taking deposits and making loans) from the risks associated with other financial services. For example, in the United States, the so-called Volcker Rule, which prohibits banks from engaging in proprietary trading (using their own money rather than trading for a client), was enacted as part of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010. In Europe, regulators in both the United Kingdom and the European Union have proposed various types of ring-fencing—separating banks’ traditional functions from the rest of their operations.

These actions, however, are based more on a fear that something bad could happen than on experience. Poor lending decisions by banks and many nonbank lenders appear to have been the main cause of the crisis, rather than nontraditional activities such as proprietary trading. Nonetheless, it may be necessary to protect traditional banking from potential damage caused by banks’ other financial activities. This decision should be based on careful consideration of the risks involved in combining banking with other financial services in a single company.

Differing risks

We found an important distinction between the risks involved in traditional banking and the risks of other financial activities that helps explain why nontraditional activities may be dangerous for banks based on two categories of financial risk: slow moving and fast moving.

Slow-moving financial risks take time to build up and cause losses over long periods, possibly months or even years. Because they accumulate relatively slowly, these risks often give advance warning that a future loss may occur. Credit, or default, risk is the leading example of a slow-moving financial risk. Often, borrowers go through periods of declining sales or other income that indicate they will have trouble repaying their loans. This longish process gives a bank time to take steps to mitigate or even prevent damage from default. For example, banks can work with their customers to prevent default by temporarily reducing or postponing payments. And even if a borrower defaults, a bank has time to work with the customer to restructure the loan to minimize the loss.

Fast-moving risks evolve quickly and inflict damage over very short periods of time. They generally do not give reliable warning signals, so it is very difficult to predict when fast-moving risks will become loss-causing events. Market risk—the potential loss from changes in market prices of assets—is the leading example of a fast-moving risk. In these days of 24-hour markets, computerized trading, and electronic communication networks, market prices can change dramatically within minutes or even seconds. For example, both stock and bond markets around the world have experienced flash crashes in recent years, in which market prices within minutes fell by large multiples of their typical daily price changes.

Because they are unpredictable, fast-moving risks pose special challenges for financial managers who try to profit from taking on exposures to these risks. If managers underestimate a fast-moving risk—and it causes a much larger loss event than anticipated—a firm’s capital can immediately be reduced by a large amount. And mitigating the damage from a loss event as (or after) it occurs is generally not possible in the case of fast-moving risks.

Thus, slow-moving and fast-moving risks must be managed differently. In addition, the firms that take on these risks may need to be structured and regulated very differently. This is why the mixing of these very different types of risk in the same institution may be dangerous—the two types of risk are not necessarily compatible.

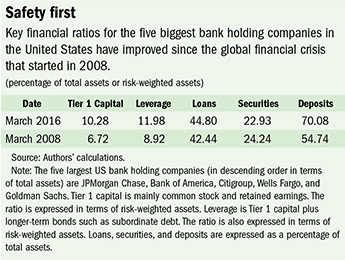

For example, think about a universal bank (or bank holding company) that takes deposits and makes loans, but also operates a division that invests in government securities. The banking division takes on the slow-moving credit risk of lending, while the investment division takes on the fast-moving market risk of investing and trading. The banking division makes relatively few new loans on any given day, but the investment division is constantly adjusting its portfolio by buying and selling government securities (see table).

Banking and trading

The banking division’s risk changes slowly because only a small amount of the total credit risk exposure changes daily, and credit risk is a slow-moving financial risk to begin with. But the risk of the investment division can change dramatically from day to day and even minute to minute. Not only is market risk a fast-moving risk—the market could conceivably crash at any time—but the continual trading by the investment division can rapidly alter the exposure of the investment division to market risks. In fact, because investment managers can adjust a bank’s exposure to fast-moving risks virtually instantaneously, they are in a position to effectively determine the overall riskiness of the bank.

There are two sides to this combination. On one hand, both the banking division and the overall institution can benefit:

- The investment division’s expected profits will help diversify the entire institution’s earnings. In addition, part of the investment division’s profits can be retained to increase the bank’s overall capital cushion—which helps protect both the banking and the investment divisions against losses. Moreover, given the fast-moving nature of trading, the investment division’s profits are probably realized more frequently than the banking division’s profits, which should smooth out the firm’s accumulation of capital.

- The investment division can also help the entire institution, including the banking division, hedge against interest rate risk. The business of banking faces significant interest rate risk because banks tend to borrow for short periods of time and lend for longer periods. This means that changes in interest rates, especially increases, can not only decrease bank income, but also reduce the value of bank capital. Banks have limited ways of hedging against interest rate risk, and it is costly to do so. The investment division of the bank, however, may be able to help by generating trading profits from changes in interest rates that offset the banking division’s losses from these changes.

But there are also downsides, potentially severe. The managers of the investment division can take advantage of the banking division’s slower pace. If the investment division takes on excessive risks, it will earn larger profits as long as these exposures do not go bad. But if they do, the investment division has recourse to an additional buffer to absorb its losses—the capital that has been set aside for the banking division. Because the investment division is taking on fast-moving risks, this effectively gives them a first-mover advantage, subjecting the lending arm to the risk from investment decisions. The managers of the investment division will therefore have a strong incentive to take on higher risks inside a universal bank than they would if the investment division were an independent company. And these higher risks could bankrupt the entire institution, even if the banking division is doing a good job managing credit risk.

Therefore, banks that mix slow-moving credit risks and fast-moving market risks could experience distress more often than banks that do not mix these risks. It’s up to the top managers of a universal bank to act in the best interests of the overall institution by ensuring that both the banking division and the investment division managers take on only prudent risks. The chief executive officers of these banks could mitigate the problem somewhat by choosing the right type of manager for the investment division. As the incentive in the investment division to take on exposure to more fast-moving risk increases, investment division managers become less risk averse. Therefore, the more prudent the manager of the investment division, the lower the likelihood of taking on excessive fast-moving risks.

Prudent managers

But there is also an important role for regulators. Bank regulators around the world follow some type of uniform system for rating financial institutions, which, among other things emphasizes not only the technical ability but also the character of bank managers. This focus on the quality of management in the bank supervision process gives regulators influence over the choice of the management team at the bank. Therefore, it is possible that bank supervisors could require CEOs of universal banks to choose investment division managers who are sufficiently prudent. Finding an objective supervisory standard to judge the prudence of investment managers, however, is likely to be difficult and controversial.

Alternatively, to limit the possibility that the investment division’s activities will plunge the entire financial institution into distress, bank supervisors could strictly limit the risk exposures the investment division of a universal bank can assume. This is also likely to be very difficult for regulators to implement, because fast-moving risks are much harder to predict than slow-moving ones. A current strategy is to include provisions in traders’ and managers’ compensation contracts, in which a large part of performance-based pay is deferred and is forfeited if trading positions lead to losses during subsequent years. Such so-called clawback provisions could reduce the incentive to take certain types of risks that are spread over longer periods, but it is unclear whether they will reduce the overall incentive to take on risk.

This regulatory dilemma is not a new one, however. Lagging behind industry changes is a fact of life for regulators and is typically called the regulatory cycle—in which a crisis spawns new laws, rules, and agencies, but the new regulation offers some unforeseen opportunities for mischief.

The new feature in today’s markets is the speed and exposure to fast-moving risks, such as investment portfolios or trading positions. In addition, it is unclear whether bank supervisors—or any financial regulator, for that matter—can monitor and enforce restrictions they place on the investment divisions of universal banks. This means that an investment division that is well behaved one day could rearrange its positions, and bankrupt the bank, the next day. Because supervisory reviews take place only periodically, fast-moving risks could cause financial distress between reviews.

Separating risks

But increasing the frequency of supervision is not the answer. Continuous monitoring and supervision would not only be extremely costly, but the process also resembles interference in the day-to-day operations of a bank. And none of this extra expense and interference is needed to improve the safety and soundness of the banking division anyway.

It may seem at first glance that the best policy would be to separate slow-moving risks from fast-moving ones, as the proponents of policies like ring-fencing argue. Such a policy, however, would not only deprive banks of the hedging benefits from managing fast-moving risks, it could also hurt financial stability. For example, losing the investment arm’s ability to sell assets short (that is, ones they don’t possess at the time of the sales agreement) would allow banks to buy (and hold) securities only. This could constrain market liquidity, which in turn could reduce confidence in the markets and damage overall financial stability.

Regulatory alternatives to ring-fencing, however, must deal with the temptation to exploit fast-moving risks in a way that is dangerous to the institution and to society. Our research suggests that such regulation should focus on strengthening oversight of bank governance, holding management accountable for identifying, measuring, monitoring, and managing risks. US banks, for example, receive a rating that emphasizes governance; it is based on capital, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and market sensitivity. But even closer collaboration between regulators and bank management may be necessary if banks are allowed to mix fast- and slow-moving risks. For example, bank supervisors may need to review the banks’ choices of division and lower-level managers to ensure that they reflect the values of the banks’ top management, including risk and leverage tolerance. The latest version of international capital standards endorsed by the Basel group of financial regulators moves in this direction, by requiring supervisors to review banks’ compensation packages. The Financial Stability Board, the international monitor of the global financial system, in its set of principles and standards for good compensation practices noted bank supervisors’ increasing emphasis on “building a culture of good conduct” among bank employees, which suggests that many regulators are already prompting banks to improve the “softer” side of their risk management practices. ■

Ralph Chami is an Assistant Director in the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development, Connel Fullenkamp is Professor of the Practice of Economics at Duke University, Thomas Cosimano is retired Professor of Finance at the University of Notre Dame, and Céline Rochon is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Strategy, Policy, and Review Department.

This article is based on a forthcoming paper, “Financial Regulation and the Speed of Financial Risks,” by Ralph Chami, Connel Fullenkamp, Thomas Cosimano, and Céline Rochon; and a 2017 IMF Working Paper, “