Set the Tone at the Top

Finance & Development, December 2016, Vol. 53, No. 4

Central bank boards benefit from the same critical reviews as company boards

Governor Bashir looks surprised and slightly amused when asked about the strengths of his central bank’s board. The septuagenarian, a seasoned Somali public official, had never been asked that before. “Well,” he says, pointing to his colleagues, “they want to rebuild the central bank. So they all wanted to join this session.”

The session in question is an orientation course the IMF organized for the board of the Central Bank of Somalia in May 2016. The central bank in this war-torn country is struggling to set up its core functions. Among the extreme challenges it faces is a domestic currency that is nearly all counterfeit. Some might consider an introspective board session the least of the central bank’s concerns. But all seven board members, the governor included, eagerly participated in an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the bank and its board. It helped: clarifying roles and responsibilities of executive and nonexecutive members, brainstorming about strategy, and outlining internal reporting requirements (who gets what information when) rooted out inefficiencies. This allowed the board to devote the little time it has to matters requiring its full attention.

Somalia may seem to be an exception, but central banks all over the world are coming to see that change starts at home, and at the top. Central bank board members call some of the key shots in any country, and effective decision making depends on the strength of those members. It is hardly surprising that their recruitment and selection are closely monitored.

Many will remember the Bank of England’s bold step in September 2012, when it advertised the vacancy for its governor in The Economist. The desired applicant, the ad said, must be “a strong communicator, have good interpersonal skills and will be a person of undisputed integrity and standing.” The quality of board members is a well-established and important component of effective board decision making, but it is hardly the only one. Since the global financial crisis, bank regulators have pushed for mandatory assessments of commercial bank boards in addition to existing requirements regarding work experience, background, and skills (so-called fit and proper requirements). Assessments often include a regular (say, annual) exercise, independently or with the assistance of external experts. These usually cover the board as a whole, its committees, and individual board members. The main goal is to improve the effectiveness and quality of actions by key decision makers. The global standard setter for commercial banks, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, published its revamped Corporate Governance Principles for Banks in 2015, including a section dedicated to board assessments. Similarly, central banks can also engage in board assessments—including of their policy, management, and supervisory boards—to improve the effectiveness of their decision making.

The business case

There are four good reasons for central bank boards to conduct assessments, just as their commercial colleagues do. First, the fields of psychology and sociology teach us that every group is made up of people—regardless of their institution or background—subject to the dangers of groupthink, hubris, dominance, and other such pressure. Behavioral economists, such as Daniel Kahneman, Cass Sunstein, Dan Ariely, George Akerlof, and Rachel Kranton, examined the effects of these psychological and sociological concepts in, for instance, the context of monetary policy decision making. In the past two decades, collective monetary policy decision making—for example, in the form of monetary policy committees—has overtaken singlehanded decisions by bank governors. A 2006 IMF study concluded that a properly designed committee is likely to improve performance when due attention is paid to greater diversity and a greater variety of viewpoints (Vandenbussche, 2006). The Bank for International Settlements noted that “Boards or committees for decision-making… are now very prevalent and have become the focus of a mushrooming field of research.” (BIS, 2009)

But there is room for improvement. Though perhaps not as extreme as in the classic Hollywood movie Twelve Angry Men (which captured the complexities of consensus building in the context of U.S. jury deliberations), when people are pressed for time and must deal with complex problems whose consequences are far reaching, fair and balanced decision making can suffer. In 2014, the Central Bank of the Netherlands conducted one of the first central bank board assessments in the world. The governor and the executive board set up an independent assessment of their interaction and performance. They hired two external experts with backgrounds in sociology, group dynamics, and more traditional corporate governance. Using interviews and questionnaires, these facilitators helped the board think about its strategy and vision, as well as practical ways to make board meetings more efficient. One concrete outcome was replacement of top managers’ general board meetings with topic-specific strategy sessions.

A second reason for assessments is the complexity of central banks. They implement a wide variety of mandates, including price and financial stability, but also financial integrity—sometimes consumer protection, and in many emerging market economies the all-encompassing yet vague “development objective.” Because central banks operate in a rapidly changing environment, it makes sense especially for these kinds of institutions to focus on continuous assessment and strengthening of their top decision makers.

Third, central banks should lead by example. Central banks request commercial banks to follow the highest corporate governance standards, including annual assessments of their boards. Central banks should be bound by the same standards. In Seychelles, for instance, the central bank is undertaking efforts to ensure it can lead by example, including in the area of board assessments.

Finally, board assessments can also help to promote diversity more than simply setting quotas, and thus improve Board decision making. On gender diversity, for example, recent studies found associations between women board members and higher risk aversion (see, for example, Masciandaro, Profeta, and Romelli, 2016). Board assessments focus on a board’s strengths and weaknesses and can define areas of competency or background requirements for board members, qualifications that fit the bank’s vision, policies, and risk profile—rather than setting quotas. Boards must decide how much risk is acceptable and must ensure its members mesh with the central bank’s strategy, policies, and risk appetite. What matters is the best people for the job.

Tips, tricks, and traps

Board assessments can backfire, though. Group dynamics, and human interaction in general, are sensitive. Forcing a board to assess itself can bring to light personal preferences, ideas, and even biases that can make people uncomfortable. If there is tension between the governor and another board member, they might be reluctant to have this discussed in an assessment, even though these are typically not disclosed outside the board. Moreover, a central bank board could include representatives from various groups and regions, which underscores the importance of the sociopolitical context and how it can strongly influence group dynamics and hinder proper assessment. Board members responsible for internal audit, the chair of the audit committee, or a lead nonexecutive director are good candidates for the role of facilitator. The head of the internal audit department, given his or her independent position, could also be suitable, as could a board secretary—but much depends on their personal standing and status vis-à-vis the board members. An internal facilitator must not be seen or treated as a subordinate.

Boards can also choose an external facilitator. Board members would still have to prepare and follow up on the assessment, but the actual facilitation (and pre-assessment analysis) would be conducted by the external expert. This person needs to be trusted by all board members and enjoy a certain amount of independence, as well as having the skills needed to truly facilitate—for example, a retired politician, a renowned academic, a senior staff member of an international organization, or even a peer from another central bank.

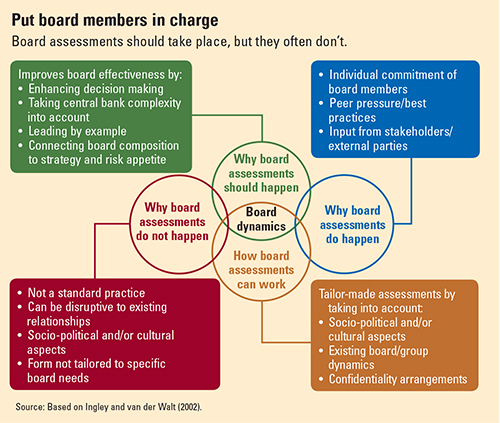

Some central bank board members say that they already have internal oversight. Central banks often have nonexecutive board members or a separate oversight body, and most have internal and external auditors. Some are subject to other forms of external oversight, either by an institution such as the auditor general or an independent evaluation office. But formal oversight is always different from an assessment with and by the board. Formal oversight ensures that the bank’s executive management conducts its business properly, and guarantees accountability to the bank’s stakeholders (government, the financial sector, international institutions). A board assessment, however, is a moment of introspection, of strengthening the ties between board members and boosting the effectiveness of collective decision making. Formal oversight can provide input, but a board assessment puts the board members themselves in charge (see chart).

Future developments

In some countries assessments have clearly improved board decision making by clarifying roles and responsibilities (for example, Somalia) or by enhancing internal organization (for example, the Netherlands). In other countries board assessments have been a role model for the financial sector (for example, Seychelles). Central banks that have already conducted board assessments should share their experiences with their colleagues on other central bank boards, in particular their close peers. International institutions and standard setters should see central bank board assessments as an additional corporate governance tool. Fit and proper criteria for board members and transparency and disclosure arrangements will all benefit.

Board assessments call for awareness among central bankers—that assessments are not a mindless check-off-the-box exercise, window dressing, or the governance equivalent of the board’s annual outing and dinner. They are a powerful tool that, used correctly, can strengthen the decision making of one of the most respected public institutions. As Peter Drucker (Drucker, 1973) said, “Long-range planning does not deal with future decisions, but with the future of present decisions.” Central bank board assessments can ensure that central bank decision making is, and stays, on point. ■

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2009, “Issues in the Governance of Central Bank” (Basel).

Drucker, Peter F., 1973, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York: Truman Talley Books/E.P. Dutton).

Ingley, Coral, and Nick van der Walt, 2002, “Board Dynamics and the Politics of Appraisal,” Corporate Governance, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 163–74.

Masciandaro, Donato, Paola Profeta, and Davide Romelli, 2016, “Gender and Monetary Policymaking: Trends, Drivers and Effects,” BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper 2015–12 (Milan).

Vandenbussche, Jérôme, 2006, “Elements of Optimal Monetary Policy Committee Design,” IMF Working Paper 06/277 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.