Flight from Quality

Finance & Development, December 2016, Vol. 53, No. 4

Natalie Chen and Luciana Juvenal

Argentine wine exports tell a tale of consumers’ shift to lower-quality goods after the global financial crisis

World trade collapsed following the global financial crisis, declining 30 percent in nominal terms between the third quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2009. Even after adjustment for inflation, the decline was a massive 18 percent.

By another measure, the ratio of world trade to GDP, there was a similar dramatic falloff. That is because the crisis disproportionately affected trade in consumer durables and investment goods, which represent a large share of global trade, but a small fraction of world GDP.

But it appears that it was not only consumers buying less that helped drive down the value of global imports and exports. Focusing on Argentine wine exports, we provide evidence that the nominal (before inflation) value of global trade fell also because consumers bought cheaper, lower-quality goods rather than more expensive, higher-quality products.

The pinch of recession

When income goes down, as typically happens during a crisis or a recession, households consume less. Because some of what they consume is imported, the demand for foreign products—that is, for imports—also falls. Importantly, however, consumer belt-tightening may affect not only how much households consume, but also the types of goods they buy. In particular, because consumption of higher-quality goods is generally more sensitive to changes in income than that of lower-quality items, a sudden reduction in income (an adverse income shock in economist parlance) may lead to a “flight from quality,” whereby households in crisis-hit countries reduce not only the quantity but also the quality of the goods they consume. This, in turn, should lead to a bigger contraction in higher- than in lower-quality imports. We investigate whether the global financial crisis induced such a flight from quality in traded goods. In the case of wine made in Argentina, that turned out to be the case.

Measuring quality is a challenge because there is no single and comparable indicator across different types of goods. But we found a way around that obstacle by focusing on the wine industry only, where well-known experts regularly assess the quality of the products. We rely on those ratings as a directly observable measure of quality and combine them with a unique data set of Argentine producers that includes information on firm-level, destination-specific export values and volumes of individual wines. We find strong evidence of a flight from quality goods. In addition, our results suggest that the change in the quality composition of exports can explain up to 9 percentage points of the decline in Argentine wine trade value during the crisis period.

Spectacular performance

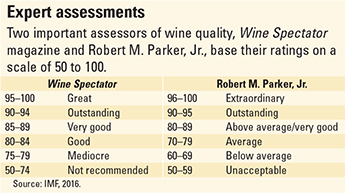

Since the early 1990s, the Argentine wine industry has grown spectacularly. By the mid-2000s, it was the fifth-biggest wine producer and eighth-largest wine exporter in the world. For the purposes of our analysis, we rely on Argentine customs data. For each export, we observe the name of the exporting firm, the country of destination, the date of shipment, the value (in dollars), and the volume (in liters) of wine exported. The data set is very rich because for each wine exported we also observe its name (the brand), its varietal grape (such as Chardonnay or Malbec), its type (white, red, or rosé), and the vintage year. To assess the quality of individual wines, we rely on ratings from two well-known expert sources, Wine Spectator magazine and wine critic Robert M. Parker, Jr. Both assign a quality score to each wine—on a scale of 50 to 100—with a higher score indicating higher quality (see table).

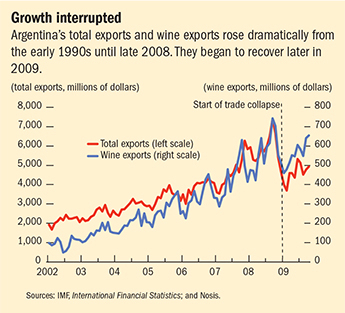

We date the episode of the trade collapse by comparing month by month both the value of Argentina’s total exports and of its wine exports (in nominal, or unadjusted for inflation, dollars). Both total exports and wine exports fell from their September 2008 peak until January 2009 and then began a slow recovery through the end of 2009. We date the start of the crisis period as October 2008 and the end a year later, in September 2009 (see chart).

We then investigate whether, during the crisis, higher-quality exports fell more dramatically than lower-quality exports. We find that before the crisis, exports of higher-quality wines grew faster than exports of lower-quality products, but the trend reversed during the crisis, when exports of higher-quality goods fell more dramatically than those of lower-quality wines. On average, for each one-unit increase on the quality scale there was a 2 percentage point decline in export growth during the downturn. We also find that the collapse in the nominal value of exports for higher-quality wines was essentially driven by a drop in quantities shipped, rather than by a cut in prices—which shows that the financial crisis affected predominantly the real side of the economy. We make allowance for all types of shocks that could affect supply and demand for the wine, from overall economic conditions that are common to all wine exports to firm-level issues (such as productivity and credit constraints). We also account for destination-specific factors such as GDP growth, protectionist measures, and bilateral exchange rates.

There are various explanations for the sharper decline in higher-quality exports. First, we find that the flight from quality was driven primarily by a crisis-induced fall in aggregate demand. The exports of higher-quality Argentine wines fell more in destination countries that were more severely hit by the crisis, including the United States and the United Kingdom. Second, we find evidence that the flight from quality was more acute in countries such as France and Italy, where households could substitute domestically produced wines for imported products. We also find that the flight from quality was stronger for the exports of smaller firms, which are typically niche producers of higher-quality wines and tend to be hit harder when household incomes fall.

Finally, we find that after the crisis export growth recovered more strongly for higher-quality wines once the world economy started to recover from the recession. This suggests that the trade effects of the crisis were only temporary.

Alternate scenarios

To assess how much quality explains wine-export behavior, we evaluate how Argentine wine exports would have performed during the crisis under two different scenarios. Under the first, we assume that the quality of all exported wines had increased during the crisis to the highest level in our data set (that is, a score of 96). Under the second, we consider the opposite extreme and assume that the ratings of all wines had instead fallen to the lowest level of quality in the sample (68). These two counterfactual alternatives provide upper- and lower-bound estimates of the hypothetical performance of trade during the crisis as a result of changes in the quality composition of exports.

We derive the predicted values of export growth for each wine shipped to each destination and compare them to the predicted values obtained under each of the two scenarios. Under the first scenario, which assumes that all wines scored 96, we estimate that total Argentine exports would have dropped by 38.94 percent, nearly 2.5 percentage points more than the actual 36.53 percent. By contrast, under the second scenario, exports would have dropped much less—by 30 percent. The two opposite scenarios therefore predict a difference in export performance of about 9 percentage points, which is not negligible. This suggests that the difference in export performance between countries that specialize in high- versus low-quality goods can be large.

Although we provide evidence of a flight from quality using firm-level data for traded goods, as in any empirical work, our analysis suffers from a number of limitations. First, because we focus only on Argentine wine exports, we are unable to address the possibility that consumers in crisis-hit countries shifted their consumption from more expensive old-world wines to less-expensive Argentine wines, which would have had ultimately kept Argentine exports from falling even more.

Second, because our analysis concentrates on a specific sector in a single country, we cannot be sure whether our findings apply more generally. But using different data sets and applying different methodologies, some studies (such as Bems and di Giovanni, forthcoming; and Burstein, Eichenbaum, and Rebelo, 2005) reach conclusions that are consistent with ours. This suggests that our findings are likely to apply to other industries and countries, in which case a number of macroeconomic implications can tentatively be drawn from our work.

First, by showing that the composition of trade shapes the way trade flows respond to economic downturns, our analysis can help policymakers and economists understand how various countries’ exports are likely to perform during recessions. In particular, because richer countries tend to produce higher-quality products, exports from these countries could suffer disproportionately during recessions (Berthou and Emlinger, 2010, show that countries specializing in higher-quality goods lose more trade during periods of global turmoil). Second, the crisis affected the volume of wine shipped more than the prices of the traded goods, which points to the large real effects of financial crises. Finally, our research has implications for understanding the distributional effects of crisis episodes: a flight from quality induced by a negative income shock can damage consumer welfare. More precisely, if consumers love variety, but also quality, a decline in the quality of products consumed reduces welfare. ■

Natalie Chen is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Warwick and has been a Visiting Scholar in the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development. Luciana Juvenal is an Economist in the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development.

This article is based on the authors’ 2016 IMF Working Paper, No. 16/30, “Quality and the Great Trade Collapse.”

References

Bems, Rudolfs, and Julian di Giovanni, forthcoming, “Income-Induced Expenditure Switching,” American Economic Review.

Berthou, Antoine, and Charlotte Emlinger, 2010, “Crises and the Collapse of World Trade: The Shift to Lower Quality,” CEPII Working Paper 2010–07 (Paris: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales).

Burstein, Ariel, Martin Eichenbaum, and Sergio Rebelo, 2005, “Large Devaluations and the Real Exchange Rate,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 113, No. 4, pp. 742–84.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.