She Is The Answer

Finance & Development, March 2016, Vol. 53, No. 1

Yuko Kinoshita and Kalpana Kochhar

Women can help offset the problems of an aging population and a shrinking workforce

The aging of populations around the world has profound implications for economic growth. When the working-age population shrinks, in many cases so does the labor force, and the potential for economic growth diminishes. In many advanced and emerging market economies, the number of working-age people is falling, which puts pressure on government revenue just as the need for spending on pensions and health care is rising.

Women play a critical role in this demographic transition. They make up over half the world’s population. Because women generally outlive men, the share of women in the over-65 age group is notably higher. Yet the percentage of working-age women who actually participate in an economy’s workforce (known as the female labor force participation rate) has hovered around 50 percent over the past two decades. The global average masks significant cross-regional differences in levels and trends. Rates vary from 21 percent in the Middle East and North Africa to more than 60 percent in east Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the United States, and northern Europe. Although Latin America and the Caribbean have experienced strong increases of some 13 percentage points during this period, rates have been declining in south Asia. Despite the stagnation in female participation, the average gender participation gap—the difference between male and female labor force participation—has been declining since 1990, but only because male labor force participation has fallen more than women’s has risen.

A chasm remains

Although the gender gap in education is narrowing, a chasm remains when it comes to other opportunities, such as access to health care and financial services, wages, and legal rights. The ratio of female to male primary enrollment rates is up to 94 percent even in the least developed economies. In secondary education, the ratio of female to male enrollment averages 97 percent, and women are now more likely than men to be enrolled in tertiary studies (college or university). These are positive developments. However, with so many highly educated women, it is even more of a loss that such a large percentage are not in the labor force.

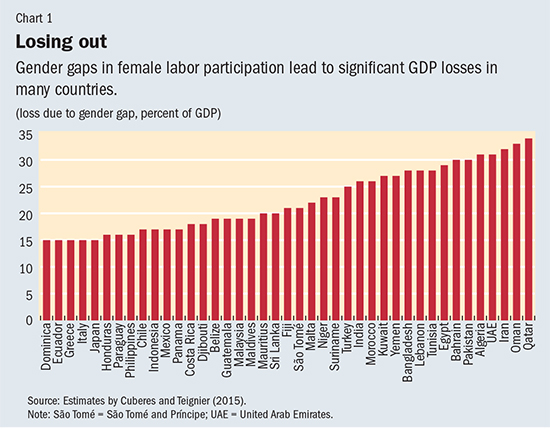

When women are able to develop their full labor market potential, significant macroeconomic gains are possible. For instance, Aguirre and others (2012) suggest that raising female labor force participation to country-specific male levels would boost GDP in the United States by 5 percent, in Japan by 9 percent, in the United Arab Emirates by 12 percent, and in Egypt by 34 percent. Cuberes and Teignier (forthcoming) estimate GDP per capita losses attributable to the gender gap in the labor market to average as high as 27 percent in certain regions (see Chart 1).

How do better opportunities for women to participate in the labor force contribute to higher incomes and growth? When women get a fair shake economic development overall can benefit. School enrollment may increase because women are more likely than men to spend their earnings on their children’s education. With equal access to inputs female-owned company productivity rises, and with fair hiring companies can make better use of the talent pool, with positive implications for potential growth. And in advanced and emerging markets with aging populations, boosting female labor force participation can mitigate the impact of a smaller workforce and spur growth.

To step up participation of women in the workforce, government and the private sector can play an important role. Government policies can target reduction in the gender gap in health, education, and infrastructure services as well as in access to financial services and can encourage provision of parental leave and child care facilities. Taxing individual incomes rather than family income has been shown to reduce the disincentive for the secondary income earner—typically the woman—to work. And in countries with gender-based legal restrictions such as constraints on female ownership of real estate or businesses, removing such limits can help lift female labor force participation (Gonzales and others, 2015). The private sector can play a role through flexibility in contracts and in the work environment and by adopting evaluation methods that reward performance rather than seniority or hours worked.

In addition to raising the number of female workers, improving the quality of jobs can boost productivity and economic growth. Women dominate nonregular and informal sector jobs. In most countries, these jobs offer fewer benefits and little job security relative to regular or full-time work. However, in Nordic countries and the Netherlands, for example, nonregular workers (including part-time workers) generally receive partial benefits and allowances. Such benefits can facilitate women’s labor participation, raise their productivity, and narrow the gender wage gap in the medium term (Kinoshita and Guo, 2015).

The view from Asia

In Asia, the role women can and should play depends on where their country is along the aging spectrum. South Asian countries such as Bangladesh and India are at the early stages of the transition, when mortality drops sharply while fertility rates remain high. East Asian countries (those in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) are in the middle stage, when birthrates begin to fall and population growth starts to level off. And advanced Asian economies such as Japan and Korea are at the later stage: birthrates have fallen below the replacement level, and the population has begun or will soon begin to shrink.

East Asia underwent a relatively rapid demographic transition between the 1960s and the 1990s, which contributed to its economic growth “miracle.” Improvements in public health reduced infant mortality and spawned a baby boom, followed by a decline in fertility. In the late 1960s, when the first of the post-World War II boomers reached working age, their entry into the workforce increased the ratio of workers to dependents. This transition was generally beneficial to women: better health and less time spent caring for children freed them up for activities such as education and employment. That virtuous cycle allowed women to both contribute to and benefit from economic growth.

In south Asian countries such as Bangladesh and India that are at the early stage of demographic transition, women are essential. To fully benefit from the potential demographic dividend, south Asia must focus on better education and skills for women, building physical infrastructure such as roads, transportation, and electricity to support all workers, and increasing labor market flexibility (Das and others, 2015). These countries must remove regulatory, institutional, and social barriers to make the best use of their talent pool and reap the highest possible dividend.

It is most critical to raise female labor force participation in advanced Asian economies such as Japan and Korea. In these countries, women hold the key to maintaining growth and offsetting the drag from aging and even declining populations. For example, in Japan, life expectancy is now 84 years, the highest in the world, while fertility rates remain low. As the baby-boom generation started to retire, the old-age dependency ratio climbed to the highest in the world.

As the working-age population declines, Japan’s GDP is likely to fall behind that of its neighbors unless output per worker rises faster than the decline in the labor force. The IMF has estimated that annual growth could rise by about ¼ percentage point if female labor force participation reached the G7 country average, resulting in a permanent rise in per capita GDP of 4 percent, compared with the baseline scenario. Higher female workforce participation would also mean a more skilled labor force, given women’s higher education levels (see “Can Women Save Japan (and Asia Too)?” F&D, October 2012).

Making better use of well-educated women is low-hanging fruit for Japan, as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe knows well—an important platform of the “Abenomics” strategy for revitalizing Japan is getting more women on the job. Since the launch of Abenomics in 2013, the number of childbearing-age women in the labor force has increased markedly thanks to expanded parental leave benefits and other policies. Although greater participation by women is crucial for countries regardless of where they fall along the path of demographic transition, for those whose population is rapidly aging the female labor supply is indispensable.

Work and fertility

A common concern is that with more women in the workforce, fertility rates will fall and exacerbate the decline in population. Indeed, for individual countries, there is evidence of a drop in the number of births as the number of women in the labor force goes up. For instance, Bloom and others (2009) find that each birth on average decreases women’s labor supply by almost two years during a woman’s reproductive life.

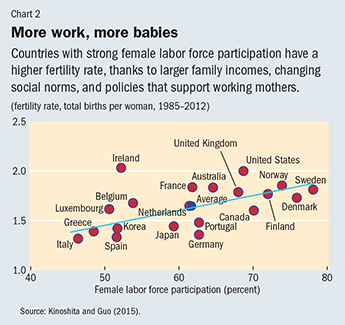

While there is a negative relationship between these variables at the individual country level, there is a positive relationship between fertility and female labor force participation at the cross-country level. Researchers have explained this apparent contradiction by looking at the contribution that men make to their households (De Laat and Sevilla-Sanz, 2011). They find that women in countries where men participate more in housework and child care are better able to combine motherhood and a job, which leads to greater participation in the labor force at relatively high fertility levels.

Moreover, the relationship between female labor participation and fertility seems to have shifted from negative to positive in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development advanced economies since 1985 (Brewster and Rindfuss, 2000). This shift implies that when more women work and bring home a paycheck households can support more children. This trend also reflects changes in social attitudes toward working mothers, fathers’ involvement in child care, and advances in technology that allow more workplace flexibility. Public policies such as more generous parental leave and greater availability of child care also helped (see Chart 2).

In the early phase of a demographic transition, women who join the labor force may choose to have fewer children. As the population shrinks, a further decline in fertility is no longer desirable or sustainable over the medium term, so policies and society at large must help support conditions that enable more women to balance work and family. ■

Yuko Kinoshita is a Deputy Division Chief and Kalpana Kochhar is a Deputy Director, both in the IMF's Asia and Pacific Department.

References

Aguirre, DeAnne, Leila Hoteit, Christine Rupp, and Karim Sabbagh, 2012, “ Empowering the Third Billion: Women and the World of Work in 2012,” Strategy & (formerly Booz and Company) report (Arlington, Virginia).

Bloom, David E., David Canning, Gunther Fink, and Jocelyn E. Finlay, 2009, “Fertility, Female Labor Force Participation, and the Demographic Dividend,” Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 79–101.

Brewster, Karin L., and Ronald R. Rindfuss, 2000, “Fertility and Women’s Employment in Industrialized Nations,” Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 26, pp. 271–96.

Cuberes, David, and Marc Teignier, forthcoming, “Aggregate Costs of Gender Gaps in the Labor Market: A Quantitative Estimate,” Journal of Human Capital.

Das, Sonali, Sonali Jain-Chandra, Kalpana Kochhar, and Naresh Kumar, 2015, “Women Workers in India: Why So Few among So Many?” IMF Working Paper 15/55 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

De Laat, Joost, and Almudena Sevilla-Sanz, 2011, “The Fertility and Women’s Labor Force Participation Puzzle in OECD Countries: The Role of Men’s Home Production,” Feminist Economics, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 87–119.

Gonzales, Christian, Sonali Jain-Chandra, Kalpana Kochhar, and Monique Newiak, 2015, “Fair Play: More Equal Laws Boost Female Labor Force Participation,” IMF Staff Discussion Note 15/02 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Kinoshita, Yuko, and Fang Guo, 2015, “What Can Boost Female Labor Force Participation in Asia?” IMF Working Paper 15/56 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).