$30 a Barrel

Finance & Development, March 2016, Vol. 53, No. 1

Oil exporters in the Middle East and North Africa must adjust to low oil prices

In early 1986, following a decision by some members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to substantially increase the supply of oil, the price nose-dived from about $30 a barrel to roughly $10 a barrel. Already feeling the adverse effects of earlier price declines and oil production cuts, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region—home to 6 of the world’s 10 largest oil exporters—faced a pressing need to adjust their budget policies. A difficult decade followed: policymakers had to make tough choices, some of which, such as cuts in public investment, had a long-lasting impact on the region.

Almost 30 years later, oil-exporting countries in the MENA region and elsewhere face a similar plunge in oil prices—which declined from roughly $110 to about $30 a barrel owing to sluggish global growth, high OPEC production, and the surprising resilience of shale oil supplies. More important, no one expects a return to triple-digit oil prices for the foreseeable future, so oil exporters must adjust to a new reality rather than wait for these low prices to come to an end. At F&D press time, futures markets were pointing to an average oil price of about $35 a barrel this year and $40 a barrel in 2017. With many MENA countries also confronting violent conflict and a growing refugee crisis, getting policy responses right and avoiding a repeat of the poor performance of the 1980s is paramount.

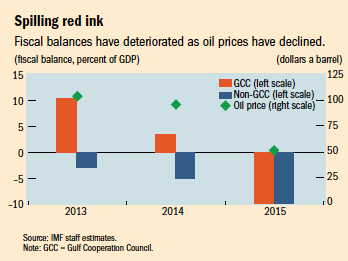

Last year, the oil price decline cost MENA oil exporters $360 billion—one-sixth of their total output. The losses are projected to deepen this year, with oil prices falling again in late 2015 and early 2016. So far, the oil exporters have, as a first line of defense, sensibly used their sizable financial savings to limit the impact of declining oil prices on growth, buying themselves time to devise adjustment plans. The clock, however, is ticking because most countries cannot sustain large budget deficits indefinitely. Half of MENA oil exporters posted double-digit deficits as a share of GDP in 2015, notably Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Libya, Oman, and Saudi Arabia (see chart).

Difficult choices

To balance their books, MENA oil exporters must make difficult choices: cutting expenditures by roughly one-third, substantially increasing non-oil revenues (multiple times in some countries), or, ideally, some combination of the two.

Most countries are making progress in addressing the challenge posed by low oil prices, and the recently announced budgets for 2016 outline cuts to spending and the introduction of new revenue sources. Saudi Arabia plans to reduce expenditures by a sizable 14 percent this year and has increased energy prices. Qatar intends to make deep cuts in nonwage current expenditures but protect funding for health, education, and major capital projects. The United Arab Emirates has eliminated fuel subsidies and curbed transfer payments, including to government-related entities. Countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—plan to inroduce a value-added tax (VAT) and raise other non-oil revenues. Non-GCC MENA oil exporters are adjusting policies as well: Algeria froze hiring and cut capital expenditures, and Iran increased the VAT and broadened its base and improved tax collection, among other measures.

These steps are an important down payment on the required fiscal adjustment. Given the large adjustment needs, the oil exporters will need to formulate medium-term plans that keep deficit reduction on track, spread measures over time to minimize the economic pain, and help prevent reform fatigue. The countries must also give careful consideration to the impact of deficit reduction on unemployment and inequality.

There is room for further reductions in operational expenditures, given the large run-up in wage, administrative, and security-related spending over the past decade. This trend has helped raise so-called budget break-even prices for oil well above current market prices—in some cases, these are near $100 a barrel. A number of governments are also trimming public investment, including by holding off on new projects. Given the previous sharp increase in government projects, there is undoubtedly room to cut waste. But, as countries learned in the 1980s, cutting investment indiscriminately could undermine future growth. In particular, some of the key outlays for health, education, and transportation infrastructure have high long-term value. Therefore, policymakers should also consider increasing the efficiency of public investment. IMF research suggests that, with the right modifications to public investment management, MENA governments could achieve the same results and spend 20 percent less.

Energy price reform can also produce significant savings, and several countries appear to be moving in this direction. The costs of keeping energy prices low across the region are significant—over $70 billion annually in the GCC countries in 2015 alone, most of which accrue to the well-off. Raising domestic energy prices, while protecting vulnerable people, would help reduce budget deficits and yield positive environmental benefits—an increasingly important consideration in light of the recent Paris accord on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Fortunately, countries are moving to address this issue. The price of gasoline in the United Arab Emirates is now close to the U.S. pretax price. Qatar recently hiked electricity and water charges and gasoline prices, and Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia have announced plans to further rein in their energy subsidies. Iran also significantly increased fuel prices last year.

In addition to spending cuts, governments must also find new sources of revenue. The current system in which more than three-quarters of all revenue typically comes from oil-related activities is untenable, and countries will have to tap more revenue from non-oil economic activity. Progress on introduction of a VAT in the GCC countries would be useful, since it is a relatively efficient, growth-friendly, and buoyant source of revenue. Meanwhile, Kuwait is preparing to introduce a business profit tax. Others should also consider broadening their corporate taxes, while revamping excise and property taxes.

New jobs

Finally, the challenge of maintaining fiscal resilience is exacerbated by the need to create jobs for a young national labor force that is expected to grow by some 10 million over the next five years. In the past, much of the non-oil growth in the region was fueled by redistribution of oil revenue through government coffers, in the form of public investment and other expenditures. Oil-rich states have become the employers of first resort, but in this environment of lower oil prices these governments cannot continue adding large numbers of new graduates to their payrolls.

Developing the private sector to create the jobs that governments can no longer provide will be challenging. It will require stronger incentives for nationals to enter the private sector, education and skills more aligned to market needs, and further improvements in the business environment. Meaningful opportunities and inclusive growth would help allay the fear of social pressure. For countries in conflict, stabilizing security conditions is an obvious prerequisite.

The transformation of oil-exporting economies is no easy task and will be a long-term project. It will require a sustained push for reforms and well-thought-out communications. Policymakers must also remain mindful of risks in other areas from lower oil prices—for example, the risk of lower asset quality and less liquidity in the financial system. The good news is that policymakers in most oil-exporting countries are increasingly determined to be proactive in addressing these challenges and to use them to transform and diversify their economies for a more sustainable economic future. ■