The Shrinking Middle

Finance & Development, March 2015, Vol. 52, No. 1

Labor market trends portend a paradise for some workers, but continued purgatory for most

Wage earners across the globe seem to be trapped in the doldrums. Global unemployment remains high, especially in some advanced economies, and every year many more workers enter the job market. More than 600 million jobs must be created over the coming decade to provide work opportunities for the more than 201 million people currently unemployed and those who will begin looking for work (ILO, 2015).

Even though some countries, such as the United States, have recently shown significant improvement in their unemployment rates, many more struggle to find new sources of jobs and incomes. And the large number of job seekers has held down wages even as productivity (output per worker) has grown, worsening inequality in many countries.

But things are changing. Longer-term shifts—such as declining middle-class jobs, a continued fallout from the global financial crisis, but also a shrinking global workforce—are shaping labor markets worldwide. Whereas the problem today seems to be a glut of workers, in coming years the global labor force will shrink. These shifts could constrain growth, but they should also help correct some of the current labor market imbalances that have prevented workers from sharing in productivity gains. The beneficiaries, however, will mainly be high-skilled workers. The prospects for lower-skilled workers are less hopeful, which is bad news not only for them, but for efforts to reduce inequality.

Inequality may worsen

Continued worsening in income inequality over the past three decades has attracted substantial attention and has been a focus of global policy debate since the publication in 2014 of Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Piketty). To be fair, the rising share of wealth and income going to the top 1 percent of the population and the fall in the labor income share had not previously gone unnoticed. But these developments were often attributed to a decline in unionization and the increased competition fostered by globalization—both of which were perceived as conducive to further and faster global growth and were expected to lift the boat for all (for example, Jaumotte and Tytell, 2007).

This view has been called into question, however, since the global financial crisis that began in 2008, because large deviations in income distribution from historical averages came at a time of highly volatile economic growth. That led some observers to argue that reducing income inequality would boost macroeconomic stability—adding an economic rationale to a purely moral imperative for a more equal distribution of riches. The current policy debate focuses on changes in taxation to address inequality but with little regard for the potential harm of increases in income or property taxes on job creation, innovation, and growth (see “Back to Basics: Taxes in Practice” in this issue of F&D). More important, this policy debate does not adequately take into account the longer-term forces shaping trends toward inequality.

A careful analysis of labor market trends reveals an ongoing shift in employment from traditional middle-class jobs in manufacturing and services toward both high- and low-skill occupations. This shift underlies much of the observed dynamics in inequality. Indeed, computers and robots seem to have finally taken center stage in the production process, eliminating many jobs that focus on routine tasks. This shift is no longer limited to manufacturing, where robots took over the conveyor belt some time ago. Even in many service sector occupations—such as accounting and health care—computers are taking over ever larger shares of the work—for example, by helping with tax preparation or providing diagnostic tools for medical doctors. For those who possess skills complementary to these “routine” tasks, computerization is creating new opportunities for productivity and wage gains (Autor, 2014).

But many more people, especially those who used to perform these tasks, are forced to compete for an ever smaller share of similar jobs or resign themselves to low-skill occupations, often accompanied by a significant loss in disposable income. On average, these trends do not preclude future rises in productivity and living standards, but so far the distribution of these gains seems to have “hollowed out” the middle class, leaving relatively more jobs at both the high- and low-skill end of the jobs scale.

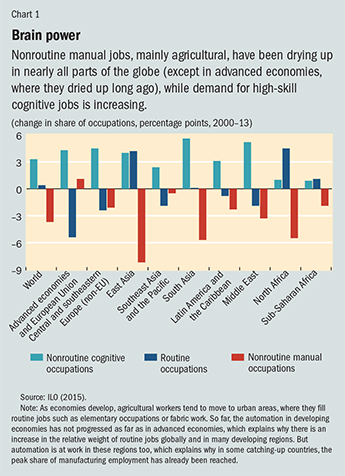

Changes largely in advanced economies

The shift in occupational employment triggered by these technological changes seems to affect mostly advanced economies (see Chart 1). In many developing economies, the more traditional shift from low- to medium- and high-skill occupations still dominates as people move from rural areas to urban centers to work in manufacturing or small-scale services. This has led to a substantial reduction in both poverty rates and vulnerable employment over the past two decades and to the emergence of a middle class in most of the developing world. The more prosperous developing economies have the potential to contribute to global growth through substantially enhanced spending power (ILO, 2013). But even in these economies, the early effects of technological changes that shift workers out of middle-class jobs are visible.

As Chart 1 demonstrates, in several middle-income regions, middle-class jobs are no longer expanding significantly, even though these jobs occupy a far smaller share of total employment than they do in advanced economies. This has led some observers to worry about premature deindustrialization: global technological dynamics in these economies, which have been viewed as catching up to advanced economies, could put middle-skill jobs under pressure much earlier in middle-income than in advanced economies and potentially reduce the growth prospects of these emerging markets significantly (Rodrik, 2013).

But as counterintuitive as it may seem in today’s high-unemployment environment, a significant threat to future global growth comes from another long-term trend: the gradual decline in the growth rate of the labor force. The number of new labor market entrants has already begun to shrink, mainly in advanced economies, but also in several emerging market economies, particularly in Asia. Currently, the youth labor force is contracting by about 4 million people a year globally. And in many countries with sustained increases in living standards, prime-age workers (those between 25 and 54) are also participating (that is working or looking for work) less actively than in the past. This partly reflects income gains—labor force participation is often high when households struggle with extreme poverty and volatile incomes, forcing all family members to seek employment, and tends to decline when conditions improve.

In addition, because the middle class has expanded in economies with higher living standards, people tend to stay in school longer, which raises the average skill level. In principle, that should help offset some of the adverse effects of a shrinking labor force on growth. The overall global labor force, however, is projected to grow much more slowly—at less than 1 percent a year in the 2020s, compared with 1.7 percent annually during the 1990s. The reduced labor force growth will shave roughly 0.4 percentage point off global growth. And the growth slowdown will be particularly acute in advanced economies, which have, on average, a more skilled workforce.

Effects of the global crisis

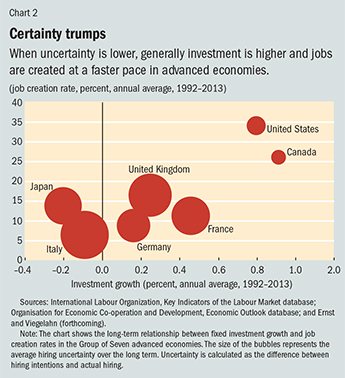

Global growth is suffering from more than inequality and a slowing increase in the labor supply. The long-term consequences of the global financial crisis continue to weigh on growth too. Investment rates remain significantly below precrisis levels, especially in some advanced economies. In addition, uncertainty among businesses remains high about the concrete policies that governments will put in place to address the consequences of the crisis, creating insecurity among businesses regarding future sources of demand for their goods and services. This depresses investment and job creation (see Chart 2). International Labour Organization estimates show that for some countries, up to 30 percent of the differential between current and precrisis unemployment stems from this high level of uncertainty in the business sector. The lack of dynamism that followed the failure of the Wall Street investment firm Lehman Brothers in September 2008 has lifted overall trend unemployment rates significantly, in some countries by up to 4 to 5 percentage points (ILO, 2014).

Moreover, weak job prospects have led to slower labor market turnover—that is, the number of employees who leave companies to take up employment opportunities elsewhere. This impedes businesses’ productivity gains because much of those gains comes in the form of new equipment and reorganization of workers both within and across companies. Interestingly, labor market turnover (also called churning) played a bigger role in productivity growth than other factors immediately after the crisis. But as the overall rate of labor market churning then declined, so did productivity growth (ILO, 2015).

A combination of high unemployment, slow growth in output, and unequal distribution of productivity gains has further eroded the income share of workers in the global economy. Only during the crisis year—largely because real wages were resistant to decline in advanced economies—did wage earners benefit from income gains that exceeded then-shrinking labor productivity. In subsequent years, however, wages once again trailed productivity growth, continuing the trend in the decades before the crisis. Although in the current environment it may be hard to see what could change that trend, in fact the declining global labor supply described above will help push wages above productivity growth—in some countries very soon.

Slowing labor force growth will help current jobseekers find new employment more easily. Especially in countries where unemployment is very high, joblessness is expected to fall significantly over the coming years. This phenomenon is reflected only imperfectly in the global unemployment rate because countries that are shifting to a more industrialized economy will experience rising unemployment. But those rising unemployment rates will often be accompanied by an increase in job quality and working conditions as people move from poorly paid, rural, and informal jobs to urban, better-paid, and formal occupations. Together, these trends should remove some of the pressure that now keeps wage growth low.

Faster wage growth

The rise in trend unemployment rates following the overall sluggish expansion of growth and investment has lifted the unemployment rate at which wages tend to accelerate during a labor market recovery. The protracted nature of the recovery will lead to faster wage growth, even if unemployment rates remain much higher than they were prior to the crisis. In countries with adequate data, this effect is evident in the fact that people out of a job for 12 months or longer do not exercise strong downward pressure on wages.

People unemployed for a long time have a hard time finding a job, and even those who are willing to accept much lower wages are not necessarily able to return to work quickly. Companies are reluctant to hire long-unemployed job seekers, who they fear lack skills and motivation. As a consequence, the long-term jobless play a relatively limited role in influencing wage dynamics. But it is exactly this group and the average duration of unemployment that increased during the crisis, so that wages react only to fluctuations in the much smaller group of those unemployed short term (Gordon, 2013).

The shift in labor demand to high-skill occupations is also poised to affect wages. As the global war for talent continues, people with the right skills not only will have plenty of job opportunities, they will also be able to garner a larger share of the productivity gains they generate. Some observers estimate that in advanced economies such as Germany and the United States demand for talent could outstrip supply as early as 2015. This demand could generate ever more pressure to attract the most talented employees with improved working conditions, profit-sharing arrangements, and higher base salaries (Conference Board, 2014). This will mean faster overall wage growth, but perhaps only for the lucky few and not for the average wage earner.

Few benefit

The dynamics of the labor income share and of income inequality will diverge. Wages are set to grow faster than productivity, at least over the medium term, given the changes in the global labor supply (see table), but the bulk of that increase will accrue only to a small group of skilled workers, no more than 20 percent of the global workforce. Hence, in contrast to the trends recorded over the past three decades, income inequality between workers and the labor income share—that is, the distribution of income between workers and capital owners—will evolve in different directions, further complicating the work of policymakers.

Not only will the distribution of productivity gains benefit only those with the right skills, the overall growth rate of the world economy will remain under pressure, in particular since labor supply is set to decelerate globally. In fact, the likely acceleration of wage growth will put a dent in profits available for future investment, further depressing companies’ appetite and willingness to expand their capacity. This means that the current slow rate of potential growth will likely continue over the medium term, which will hurt emerging market economies and keep them from catching up with advanced economies and further reducing poverty. All this suggests a possible worker paradise on the horizon, with lower unemployment, better working conditions, and higher salaries. But the only ones likely to be admitted into that paradise are those with the right skills—and at the cost of slower improvement in living standards and poverty reduction across the globe. ■

Ekkehard Ernst is Chief of the Job-friendly Macroeconomic Policy Team at the International Labour Organization.

References

Autor, David H., 2014, “Polanyi’s Paradox and the Shape of Employment Growth,” paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, August 22.

The Conference Board, 2014, From Not Enough Jobs to Not Enough Workers: What Retiring Baby Boomers and the Coming Labor Shortage Mean for Your Company (New York).

Ernst, Ekkehard, and Christian Viegelahn, forthcoming, “Hiring Uncertainty: A New Labour Market Indicator” (Geneva: International Labour Organization).

Gordon, Robert J., 2013, “The Phillips Curve Is Alive and Well: Inflation and the NAIRU during the Slow Recovery,” NBER Working Paper No. 19390 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research).

International Labour Organization (ILO), 2013, Global Employment Trends 2013 (Geneva).

———, 2014, Global Employment Trends 2014: The Risk of a Jobless Recovery (Geneva).

———, 2015, World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2015 (Geneva).

Jaumotte, Florence, and Irina Tytell, 2007, “How Has the Globalization of Labor Affected the Labor Income Share in Advanced Countries?” IMF Working Paper 07/298 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Picketty, Thomas, 2014, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press).

Rodrik, Dani, 2013, “The Perils of Premature Deindustrialization,” Project Syndicate, October 11.