Point of View

The Foremost Priority

Finance & Development, March 2015, Vol. 52, No. 1

It’s time for a recovery led by wages and public investment

The global employment deficit remains a glaring indictment of the failures of economic policies applied in the postcrisis period, more than six years after the start of the worst global financial crisis and recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

According to the International Labour Organization’s (ILO’s) World Employment and Social Outlook, the global unemployment rate in 2014 was 5.9 percent, representing more than 200 million people out of work, and considerably higher than the 2007 precrisis rate of 5.5 percent.

These figures do not take into account the hundreds of millions of workers who are underemployed, work in informal economy jobs, or do not earn enough to raise themselves and their dependents above the poverty line. The ILO notes that some 760 million workers, who represent 28 percent of the employed population in developing countries, are in the category of “working poor”—earning less than $2 a day.

Nor does the ILO’s jobless figure include those no longer engaged in fruitless job searches (so-called discouraged workers). This explains why labor force participation in 2014 was even lower than at the height of the recession in 2009. Because of the lower participation rate, the ILO projected a global employment-to-population ratio of 59.7 percent in 2014, the same as in 2009 and well below the 2007 precrisis figure of 60.7 percent.

Policy shortcomings

For the first two years after the start of the crisis, the international community, via the Group of 20 advanced and emerging market economies (G20) and international organizations, led a concerted effort to save the financial sector from collapse, stop the downward spiral of global economic activity, and help get the global labor force back to work. But once the first two objectives were achieved, with the financial sector stronger than ever and profits back to precrisis levels, the third objective was abandoned.

Bailouts of the financial sector and stimulus policies to end the recession gave way in 2010 to premature and frequently self-defeating efforts to reduce fiscal deficits, most often through cuts in social programs and other public expenditures and increases in regressive taxation.

These policies not only worsened the conditions of those most dependent on state support, but they cut short the fragile recovery in many countries, most particularly in the euro area, which by 2012 had fallen into a double-dip recession. The purported objective of the austerity policies to reduce public indebtedness was also an abject failure, as in country after country new recessions resulted in increased ratios of debt to GDP.

Lagging wages

A significant feature of the postcrisis period is the compression of aggregate demand resulting from persistently high unemployment as well as from the failure of wages to keep up with productivity. A report jointly prepared in September 2014 by the ILO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Bank (ILO, OECD, World Bank; 2014) notes this phenomenon and how it prevented a robust recovery and exacerbated inequality:

“Wage growth has significantly lagged behind labor productivity growth in most G20 countries. The decline in labor’s share of income observed in most G20 countries over recent decades has continued in some while in others the labor share has stagnated. Wage and income inequality has continued to widen within many G20 countries . . . Re-igniting economic growth . . . depends on recovery of demand, and this in turn requires stronger job creation and wage growth.”

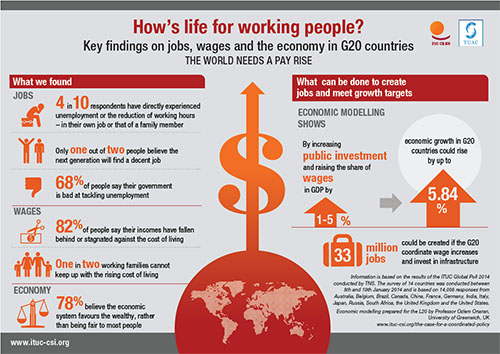

According to an International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) global poll of the general public in 14 countries, only half of respondents believe that the next generation will find a decent job. Eighty-two percent say their incomes have fallen behind the cost of living or are stagnant, and half of working families say they cannot keep up with the rising cost of living. Seventy-eight percent believe that the economic system favors the wealthy and is not fair for most people.

Global recovery strategy

The global trade union movement has sought to respond to the long-term economic stagnation and high unemployment and underemployment resulting from deficient demand. It has put forward a global recovery strategy that hinges on the restoration of wages and investment in public social and physical infrastructure.

An ITUC modeling exercise found that a policy mix of coordinated wage increases and public investment stimulus could lead to 5.8 percent higher growth in the G20 countries in the next five years (ITUC, 2014). A wage- and investment-led recovery strategy would also help attain the objectives of social, environmental, and fiscal sustainability and reduced inequality.

While the increased attention to the issue of inequality by the IMF and other international organizations is certainly welcome, most institutions have yet to develop consistent and coherent approaches that encompass and respond to all the causes of growing inequality, and most particularly to developments in labor market institutions and policies.

Along with policies such as austerity that depress aggregate demand, policies that decrease employment security and weaken minimum standards can reduce labor income and skew overall income distribution.

The ILO notes in its Global Wage Report 2014/15 that “inequality starts in the labor market.” In economies where inequality increased the most, the phenomenon can often be traced to loss of income as result of higher unemployment combined with increased wage inequality. The report found, however, that in emerging market countries where—contrary to global trends—inequality declined, “a more equitable distribution of wages and paid employment was a predominant factor.”

This highlights the importance of policies such as minimum living wages, protections against unjust dismissal, and robust collective bargaining institutions. Some international institutions have advocated weaker labor market regulations and institutions on an unfounded assumption that there is a strong and systematic negative relationship between the level of regulation and employment.

The World Bank, which devoted its flagship World Development Report 2013 to the theme of jobs, undertook an extensive review of recent economic literature on the impact of employment-protection legislation and minimum wages. The report found that “most estimates of the impacts [of labor regulations] on employment levels tend to be insignificant or modest.” It also found that “it is clear that unions and collective bargaining have an equalizing impact on earnings differentials.”

Policies that seek to deregulate labor markets and weaken collective bargaining have been an important feature of some of the adjustment programs supported by the IMF, most particularly in the recent post–global crisis period in southern and eastern Europe. Some countries have seen significant declines in real wages and a dramatic drop in collective bargaining coverage.

The immediate impact has been a sharp decline in domestic demand, intensifying the recessionary impact of austerity policies and contributing to unemployment levels of 25 percent or more in some countries. There are signs that inequality has increased in those countries and will get worse in the future. Organized labor has been the strongest constituency in favor of comprehensive social protection and progressive taxation—weakening its role will have consequences not only for wage levels but also for potentially far-reaching redistributive policies.

It is time to get the global agenda back on track, making job creation the foremost priority. Another six years of global employment stagnation, accompanied by outright depression in some countries, is unacceptable.

According to the ITUC global poll, people around the world want their governments to be more activist. They want governments to tame corporate power (62 percent) and to tackle climate change (73 percent).

The global labor movement has a clear view of the work that must be done: raise wages and social protection, tame corporate power and eliminate wage slavery, and secure climate justice and good economic governance. And back it all up with jobs, jobs, jobs. ■

References

International Labour Organization (ILO), 2014, Global Wage Report 2014/15: Wages and Income Inequality (Geneva).

International Labour Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and World Bank (ILO, OECD, World Bank), 2014, “ G20 Labour Markets: Outlook, Key Challenges and Policy Responses,” Report prepared for the G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Meeting, Melbourne, September 11.

International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), 2014, “The Case for a Coordinated Policy Mix of Wage-Led Recovery and Public Investment in the G20,” economic modeling results prepared for the L20 elected representatives of trade unions from G20 countries.