Toil and Technology

Finance & Development, March 2015, Vol. 52, No. 1

Innovative technology is displacing workers to new jobs rather than replacing them entirely

At the Quiet Logistics distribution center north of Boston in the United States, a robot lifts a shelf and transports it through the warehouse to a workstation. There, an employee picks an item from the shelf and places it in a shipping box. Each robot in the distribution center does the work of one and a half humans.

Robots and other technologies are transforming supply chains, tracking items from source to consumer, minimizing shipping time and cost, automating clerical tasks, and more. But are they eliminating the need for human workers, leading to persistent technological unemployment?

Surprisingly, the managers of warehouses and other supply chain facilities report that they have difficulty hiring enough workers, at least enough with the skills needed to use the new technologies. Moreover, they see these skill shortages persisting for the next decade.

New “smart machines” are radically changing the nature of work, but the question is how. Powered by artificial intelligence, new technologies are taking over tasks not only from warehouse workers, but also from white-collar workers and professionals. Automated teller machines have taken over the tasks of bank tellers; accounting software has automated the work of bookkeepers. Now computers can diagnose breast cancer from X-rays and predict survival rates at least as well as the average radiologist.

What, exactly, does this mean for jobs and wages? Sometimes new technologies eliminate jobs overall, but sometimes they create demand for new capabilities and new jobs. In one case, the new machines replace workers overall; in the other, they just displace workers to different jobs that require new skills. In the past, it has sometimes taken decades to build the training institutions and labor markets needed to develop major new technical skills on a large scale.

Policymakers need to know which way technology is headed. If it replaces workers, they will need to cope with ever-growing unemployment and widening economic inequality. But if the primary problem is displacement, they will mainly have to develop a workforce with new specialized skills. The two problems call for very different solutions.

Despite fears of widespread technological unemployment, I argue that the data show technology today largely displacing workers to new jobs, not replacing them entirely. Of the major occupational groups, only manufacturing jobs are being eliminated persistently in developed economies—and these losses are offset by growth in other occupations.

Yet all is not well with the workforce. The average worker has seen stagnant wages, and employers report difficulty hiring workers with needed technical skills. As technology creates new opportunities, it creates new demands as well, and training institutions are slow to adapt. Although some economists deny that there are too few workers with needed skills, a careful look at the evidence below suggests we face a significant challenge building a workforce with the knowledge needed to use new technologies. Until training institutions and labor markets do catch up, the benefits of information technology will be limited and not widely shared.

Automation ≠ unemployment

I focus on information technology because this technology has brought dramatic change to a large portion of the workforce. Some people see computers automating work and conclude that technological unemployment is inevitable. A recent study (Frey and Osborne, 2013) looks at how computers can perform different job tasks. It concludes that 47 percent of U.S. employment is in occupations that are at high risk of being automated during the next decade or so. Does that mean nearly half of all jobs are about to be eliminated?

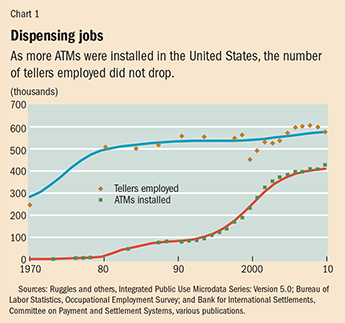

Not likely. Just because computers can perform some job tasks does not mean that jobs will be eliminated. Consider bank tellers. Automated teller machines (ATMs) were first installed in the United States and other developed economies in the 1970s. These machines handle some of the most common tasks bank tellers performed, such as dispensing cash and taking deposits. Starting in the mid-1990s, banks rapidly increased their use of ATMs; over 400,000 are installed in the United States alone today.

One might expect such automation to decimate the ranks of bank tellers, but in fact the number of bank teller jobs did not decrease as the ATMs were rolled out (see Chart 1). Instead, two factors combined to preserve teller jobs.

First, ATMs increased the demand for tellers because they reduced the cost of operating a bank branch. Thanks to the ATM, the number of tellers required to operate a branch office in the average urban market fell from 20 to 13 between 1988 and 2004. But banks responded by opening more branches to compete for greater market share. Bank branches in urban areas increased 43 percent. Fewer tellers were required for each branch, but more branches meant that teller jobs did not disappear.

Second, while ATMs automated some tasks, the remaining tasks that were not automated became more valuable. As banks pushed to increase their market shares, tellers became an important part of the “relationship banking team.” Many bank customers’ needs cannot be handled by machines—particularly small business customers’. Tellers who form a personal relationship with these customers can help sell them on high-margin financial services and products. The skills of the teller changed: cash handling became less important and human interaction more important.

In short, the economic response to automation of bank tellers’ work was much more dynamic than many people would expect. This is nothing new. Automation during the Industrial Revolution did not create massive technological unemployment. During the 19th century, for example, power looms automated 98 percent of the labor needed to weave a yard of cloth. Yet the number of factory weaving jobs increased over this period. Less labor cost per yard meant a lower price in competitive markets; a lower price meant sharply increased demand for cloth; and greater demand for cloth increased the demand for weavers despite the drop in labor needed per yard. Furthermore, while technology automated more and more weaving tasks, weavers’ remaining skills, such as those needed to coordinate work across multiple looms, became increasingly valuable. Weavers’ wages rose sharply compared with those of other workers during the late 19th century.

The economy responds dynamically in other ways as well. In some cases, new jobs are created in related occupations. Desktop publishing meant fewer typographers but more graphic designers; automated company phone systems meant fewer switchboard operators but more receptionists who took over the human interaction tasks switchboard operators previously performed. In each case, the new jobs required new and different skills. Sometimes new jobs appear in entirely unrelated sectors. For example, as agricultural jobs disappeared, new jobs arose in the manufacturing and service sectors.

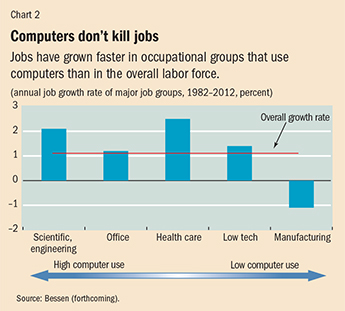

Thus computer automation does not necessarily imply imminent and massive technological unemployment; new technology can also increase the demand for workers with new skills. To measure the actual effect of computer technology on jobs overall, we must look at major occupational groups to capture the net effect when jobs switch to related occupations.

Chart 2 shows the annual growth rate of jobs in five major occupational groups, listed in order of declining computer use; over half the workers in each of the first three groups used computers at work as of 2001. In all three computer-intensive groups, jobs grew faster than the overall labor force. In other words, computers have caused job losses in some specific occupations, but the net effect on these broad occupational groups has not been technological unemployment. Only manufacturing has experienced a net loss in jobs—5 million jobs over three decades. Yet employment growth in the rest of the economy offset these losses.

In short, during the three decades since the advent of the personal computer, technology has not been replacing workers on the whole. But that might be about to change. Some people, such as science fiction writer Vernor Vinge—also a retired professor of mathematics and a computer scientist—argue that we are approaching the “technological singularity”: within a decade or so computers will become “smarter” than humans. When this happens, they say, technology really will replace human workers on a massive scale. Perhaps they are right, but many computer scientists remain skeptical.

New technology will surely take over more tasks that humans perform, but many human qualities will remain important in global commerce. Although computers can pick stock portfolios, financial advisors provide reassurance when markets are down. Although computers can recommend which products to buy, salespeople understand consumer needs and inspire confidence that unforeseen contingencies will be handled fairly. Although computers can make accurate medical prognoses, they don’t yet have the bedside manner to guide patients through difficult medical choices. And computer scientists don’t foresee computers acquiring such capabilities anytime soon.

So while technological unemployment might become a significant problem in the future, it is not a major problem today nor is it likely to become one in the immediate future. Policymakers should not focus on responding to an ill-defined and uncertain threat of future technological unemployment when information technology is causing some very real problems for both employees and employers right now.

New skills for new technology

Supply chain managers are not the only executives reporting difficulty finding workers who have the skills to use new technology. The U.S.-based company ManpowerGroup conducts an annual survey of 38,000 managers worldwide. Last year, 35 percent of managers reported difficulty hiring workers with needed skills. Other surveys have reported similar figures.

But some economists are deeply skeptical about employer complaints of a talent shortage. Some, such as economist Peter Cappelli, argue that the number of educated workers exceeds the number required for today’s jobs. However, the missing skills are too often technology related and learned through job experience, not in school, so employers can face skill shortages despite high levels of schooling.

Other economists argue that there must not be a skill shortage because average wages aren’t rising. The Brookings Institution’s Gary Burtless writes, “Unless managers have forgotten everything they learned in Econ 101, they should recognize that one way to fill a vacancy is to offer qualified job seekers a compelling reason to take the job” by offering better pay or benefits. Since the median wage is not increasing, Burtless concludes that there is no shortage of skilled workers.

Burtless is right that wages will be bid up for workers who have needed skills, but he apparently assumes that median workers already possess the skills employers want. That seems unlikely if they have difficulty learning the skills to handle the very latest technology. In that case, some workers will learn and enjoy rising wages, but others, including the median worker, will see their skills become obsolete and earn stagnant or even falling wages.

Developing skills to implement new technology is not a new problem. In the past, training institutions and labor markets sometimes took a long time to adapt to major new technologies. For example, during the Industrial Revolution, factory wages were stagnant for decades until technical skills and training were standardized; when that happened, factory wages rose sharply.

Something similar seems to be happening today. Consider, for instance, graphic designers. Until recently, graphic designers worked mainly in print media. With the Internet, demand grew for Web designers; with smartphones, demand for mobile designers increased. Designers had to keep up with new technologies and new standards that continually change.

In this environment, schools can’t keep up. Most graphic arts schools are still oriented toward print design, and much of what they teach quickly becomes obsolete. Instead, designers have to learn on the job, but employers don’t always provide strong incentives to do so. Employers are reluctant to invest in learning when employees leave and technology changes. Moreover, because new technology is often not standardized, skills learned at one job are not valuable to other employers, so they don’t bid up wages. And employees are reluctant to invest on their own without a robust labor market for their skills and a long-term career path.

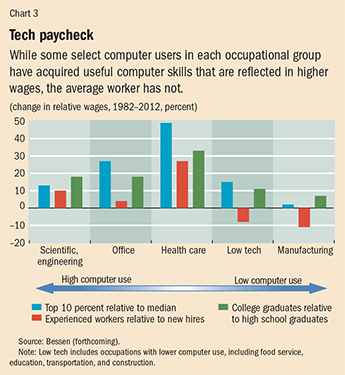

Yet the most talented designers teach themselves the new skills and establish reputations that help inform potential employers. The top 10 percent of designers command six-figure salaries in U.S. dollars or earn high hourly rates as freelancers. Meanwhile, the wages of the median designer have changed little; the median designer, after all, is still mainly a print designer. Employers will pay high salaries to designers with the right skills and reputation, but until training and labor market institutions catch up, the supply of those designers will be limited. And for 30 years the median designer’s wage has remained stagnant precisely because these institutions have not kept up with continually changing technology.

As a result there is growing economic inequality within the occupation: the difference between the wages of the top 10 percent of designers and those of the median designer has grown sharply. This pattern is seen in other occupations affected by computers.

Chart 3 shows evidence of rising demand for select workers within computer-intensive occupations. The blue bars show the growth in wages for the 90th percentile compared with the median worker within each occupational group. For office and health care occupations, wages have grown much more rapidly for the top 10 percent of workers, implying that these workers have valuable skills while the average worker in these groups does not. To the extent that these valuable skills are acquired through experience and education, wages have also risen more rapidly for experienced workers compared with new hires (red bars) and for workers with college degrees compared with high school graduates (green bars) in computer-intensive occupations.

These data show that employers do pay higher wages, but only to workers who have learned particular skills in computer-related occupations. Many of these workers teach themselves and learn through job experience. But the average worker finds it too difficult to acquire the necessary knowledge of new technologies.

Policy implications

New information technologies do pose a problem for the economy. To date, however, that problem is not massive technological unemployment. It is a problem of stagnant wages for ordinary workers and skill shortages for employers. Workers are being displaced to jobs requiring new skills rather than being replaced entirely. This problem, nevertheless, is quite real: technology has heightened economic inequality. But the skills problem can be mitigated somewhat by the right policy actions by firms, trade associations, and government.

For example, the U.S. materials handling association known as MHI runs a program to encourage specialized training programs at four-year colleges, community colleges, and even high schools. Industry associations jointly prepared a technology “roadmap” that calls for efforts to retrain workers from other occupations and attract demographically diverse workers to the field.

The roadmap recognizes that some key skills are not taught in schools but are learned through experience. To foster career paths for workers who learn on the job, the institute proposes a national center to certify such skills. The roadmap also proposes greater collaboration and information sharing between firms so that technology and skills can be standardized.

The information technology revolution may well be accelerating. Artificial intelligence software will give computers dramatic new capabilities over the coming years, potentially taking over job tasks in hundreds of occupations. But that progress is not cause for despair about the “end of work.” Instead, it is all the more reason to focus on policies that will help large numbers of workers acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to work with this new technology. ■

James Bessen is Lecturer in Law at the Boston University School of Law; this article draws on his forthcoming book, Learning by Doing: The Real Connection between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth.

Reference

Frey, Carl Benedikt, and Michael A. Osborne, 2013, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Oxford Martin Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology working paper (Oxford, United Kingdom).