Jobless in Europe

Finance & Development, March 2015, Vol. 52, No. 1

A solution to unemployment in the euro area demands both growth and a more flexible labor market

No country, however rich, can afford the waste of its human resources. Demoralization caused by vast unemployment is our greatest extravagance. Morally, it is the greatest menace to our social order.—Franklin Delano Roosevelt, September 30, 1934

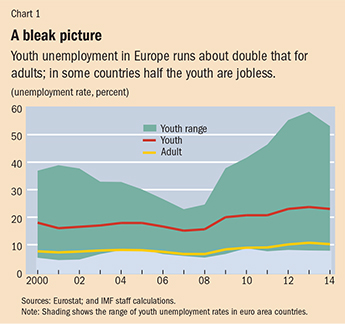

Eighteen million workers were unemployed in the euro area at the end of June 2014, more than the entire population of the Netherlands. Three million of those unemployed were between the ages of 15 and 24. But the absolute numbers don’t provide a full picture of youth unemployment (see Chart 1).

Scaling the number of unemployed workers by the labor force reveals a dire situation. The unemployment rate among young workers is at an all-time high in some countries in the euro area. The youth unemployment rate has always been higher than the adult rate because of the region’s rapidly aging population, which means that the 15- to 24-year-old workforce is smaller than the adult (older than 25) workforce. But the youth unemployment rate has increased faster than that for adults since the global financial crisis began in 2008, though there is wide divergence across countries. At the end of June 2014, more than 2 in 10 young workers were unemployed compared with 1 in 10 adult workers.

The young, the old, and the restless

U.S. President Harry S. Truman famously said, “It’s a recession when your neighbor loses his job; it’s a depression when you lose your own.” Some commentators have pointed to the differences in magnitude between adult and youth unemployment and wondered whether there is a need to focus specifically on unemployment among younger workers.

All workers contribute to an economy’s capacity to grow by providing vital labor resources. Therefore, all unemployment is cause for concern.

The longer workers stay unemployed, the less they are able to produce because their skills become less relevant over time. This limits the economy’s ability to grow its way out of a recession; recessions end up lasting longer because of a less productive workforce. So it is of great concern that more and more workers in the euro area have now been unemployed for a year or longer, joining the ranks of the so-called long-term unemployed. The share of long-term unemployment was 53 percent for all unemployed workers and 40 percent for young unemployed workers in June 2014.

While unemployment places a heavy burden on all workers, high youth unemployment deserves special attention.

The experience of early job loss can “scar” workers (see “Scarred Generation,” in the March 2012 F&D), lowering their chances of finding gainful employment at a decent wage in the future. Many researchers have found substantial evidence of such scarring. These effects can persist for longer than a decade, affecting generations of workers.

Moreover, one has only to glance at newspaper headlines to see how high youth unemployment can affect social cohesion, making progress with sorely needed difficult reforms even harder. Several studies have empirically documented this relationship. Studies also show that the experience of unemployment during one’s formative years can reduce confidence in socioeconomic and political institutions and lead to elevated crime rates.

Perhaps most noteworthy for adult workers who are employed, high unemployment among the younger age groups can make social safety nets less sustainable. Given the aging population, the dependency ratio—the number of workers needed to support each retiree—has been rising gradually over the years. The burden of supporting a growing number of retired workers is being spread across fewer and fewer younger workers. High and persistent youth unemployment adds to these concerns.

To be sure, the rising dependency ratio could be mitigated by inward migration of workers to replenish the workforce. But there are practical limits to how much immigration can solve the problem (see “A Long Commute,” in this issue of F&D). And the reality has been quite different, as the crisis has led to a net outflow of migrants from the vulnerable countries in the euro area. Furthermore, there is some evidence that high-skilled young workers are the ones heading for the exit, choosing to study and work abroad.

So it is in the interest of society as a whole to solve the youth unemployment problem in the euro area.

Common solutions

The good news is that addressing youth unemployment should not come at the expense of neglecting adult unemployment. The IMF recently published research (Banerji and others, 2014) that examines what is driving unemployment in a group of 22 advanced economies in Europe. The study finds that youth and adult unemployment have much in common: they are to a large extent driven by the same factors and can be addressed to different degrees by the same policies.

But some factors are “more equal than others,” as George Orwell might have said. Our study finds one of the most important drivers of unemployment in Europe is output growth. Changes in economic activity explain on average about 50 percent of the increase in youth unemployment since the crisis and about 60 percent of the increase in adult unemployment. The importance of growth varies across countries; one extreme example is Spain, where fluctuations in economic activity seem to account for 90 percent of the increase in the youth unemployment rate during the crisis.

These numbers are likely conservative estimates. Labor markets tend to have many quirks that are relevant for individual countries but are difficult to generalize or measure in a consistent manner for all countries. Many facets of the economy also influence how, and how soon, changes in policies and economic output affect labor market outcomes. For instance, during the crisis German firms chose to hold on to their workers given their prior experience with labor shortages. As a result, German workers worked fewer hours on average instead of being laid off.

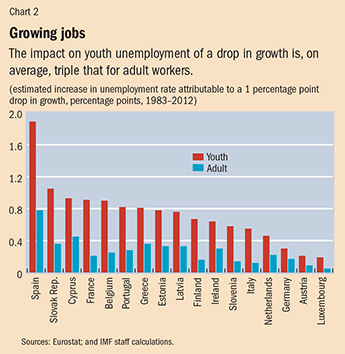

Clearly, policies that raise economic growth benefit all workers in all countries. But there are significant differences across countries in the degree to which changes in economic outcomes will lower unemployment (see Chart 2). The largest responses would occur in the most vulnerable euro area countries—for example, Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. In countries such as Germany with low unemployment rates the responses would be much smaller. Regardless of these variations, in all countries, the youth unemployment rate responds more strongly than the adult unemployment rate to output growth—about three times more strongly on average.

The large effect of growth on youth unemployment can be explained by the fact that employment conditions for young workers tend to be more fragile than for adult workers. Young workers are three times more likely to be hired on temporary contracts than adults in the euro area. They also work in sectors of the economy that are vulnerable to recessions. For example, one in four young workers in Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain was employed in the construction sector before the housing market bust. These employment conditions mean young workers are the last in but first out of jobs in a downturn.

More flexible markets

The IMF study also finds that inflexible labor markets can foster higher youth and adult unemployment and that some of these characteristics—such as employment protection under work contracts—are particularly relevant for young workers. Thus labor market reforms can help lower unemployment.

A prominent example of such beneficial reforms is taxes on labor. A smaller labor tax wedge—the difference between workers’ cost to employers and their net earnings—makes hiring less costly, increases the demand for workers, and benefits all unemployed workers regardless of age.

Young workers face an additional constraint. They are more likely than adults to earn the minimum wage since they are often low skilled. Because wages gradually adjusted downward in many euro area economies during the crisis, it is important to ensure that the minimum wage is not too high relative to average wages in an economy, which risks making young workers too expensive to hire relative to adult workers.

Lowering the opportunity cost of working—for example, by reducing overly generous unemployment benefits—can also reduce both adult and youth unemployment. This is because smaller financial incentives for staying unemployed can induce workers to seek and accept job offers they may not otherwise pursue.

Another reform that can help get people back to work is to ease employment protection requirements on work contracts. This can significantly reduce both youth and adult unemployment. But it has a bigger impact on youth rates because of the disproportionately high incidence of temporary contracts in the 15 to 24 age group. Large differences between protection afforded by temporary and permanent contracts (or “labor market duality”) risk locking young workers into a permanent underclass, with employers unwilling to make the necessary investments in their human capital.

One way to address this problem is by marrying temporary employment contracts with industry-led skill building. Improving vocational training systems would be particularly helpful for young workers. In vulnerable euro area countries, only one in four young workers on temporary job contracts is in a vocational training or apprenticeship program, unlike in countries such as Austria and Germany, where such training is almost the norm. Several countries in Europe have used such vocational training systems to great effect to limit scarring and ready workers for the workplace.

Gearing active labor market policies toward young workers can be helpful. These programs intervene in markets to reduce unemployment, but currently most such programs do not target young workers. Programs should be tailored to the institutional, economic, and social context of individual countries given evidence that there is no one-size-fits-all program that would work well in all countries. And the success of such programs is by no means assured unless they are well designed and implemented. The IMF study recommends increased focus on education and on-the-job training targeted at developing occupational skills.

Long road to full employment

High unemployment in the euro area today is a consequence of both the economic fallout from the global financial crisis and labor market rigidities that predate the crisis in many countries. It would be helpful for all workers if policies focused on fixing the weak economy and the malfunctioning labor market.

The top priority of policymakers should be to revive growth through a combination of supportive monetary policy, more public investment by countries with sufficient leeway in their budgets to do so, and measures to help banks resume lending. Without strong growth, it will be difficult to make a sizable dent in unemployment. It is also important to push forward on critical reforms that make it easier for firms to hire, ensure a level playing field for all workers, and allow workers to preserve and enhance their skills while they are between

jobs. ■

Reference

This article is based on the recently published IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/11, “Youth Unemployment in Advanced Economies in Europe: Searching for Solutions,” by Angana Banerji, Sergejs Saksonovs, Huidan Lin, and Rodolphe Blavy.