Going Local

Finance & Development, December 2014, Vol. 51, No. 4

Victoria Fan and Amanda Glassman

In emerging and developing economies, public health spending is moving from central governments to states and cities

Nothing is certain but death and taxes, or so the saying goes.

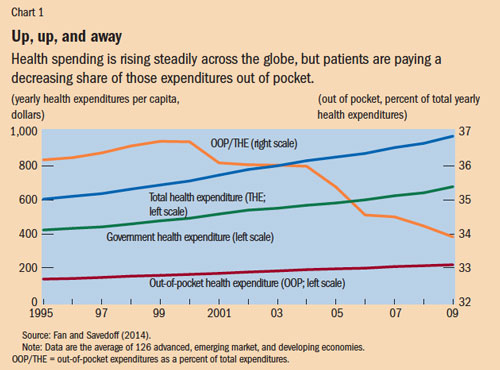

Economists might add a third certainty: health spending growth. As countries grow economically, two important trends converge as part of a health financing transition—health spending per person increases and out-of-pocket spending on health services decreases (see Chart 1).

But if increases in total health spending seem inevitable, declines in impoverishing health payments are not. Despite reduced out-of-pocket spending on average, many households are still devastated by medical bills, especially in low-income countries. Research suggests that government or public mobilization of resources for health—and with it policies that improve the efficiency of public money for national health systems—must grow if out-of-pocket spending is to continue to shrink.

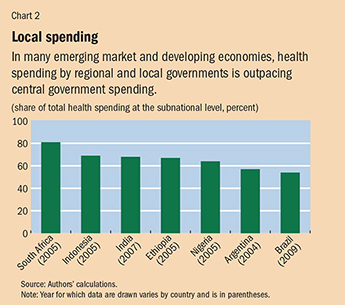

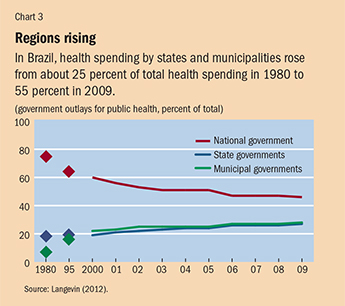

Yet much public spending for health does not take place at the national level—particularly in large federal countries with self-governing regional entities such as states and provinces (see Chart 2). Many tough decisions on how to allocate public health funds efficiently and effectively are made not in a capital city but by regional and local governments. In advanced economies this is nothing new. As incomes rise in emerging market and developing economies and as they continue to democratize, decentralize, and urbanize, spending by subnational governments will likely continue to grow. In Brazil, for example, subnational spending on health rose from 25 percent to 55 percent of total public health spending between 1980 and 2009 (see Chart 3).

Yet the effectiveness of regional and local government health systems spending on improving health outcomes and reducing medical impoverishment varies widely. Moreover, in too many cases, public health systems—which aim to protect well-being through prevention programs such as vaccination and surveillance and control of epidemics such as the recent Ebola outbreak—take a backseat to the more visible and prestigious medical functions that treat diseases, often in hospitals, with expensive technologies, achieving small health gains.

These trends warrant an examination of subnational spending on health—including successful local health reforms in emerging market and developing economies, and central government efforts to spur local innovation and performance.

Local moves

Many subnational entities have undertaken successful reforms in health, health care, and wellness, even as national reforms foundered. These include changes in financing and payment, organizational and regulatory actions, and even attempts to change individual behavior, by encouraging exercise or discouraging smoking.

Some of these changes have occurred in advanced economies. In the United States, for example, the state of Massachusetts undertook an expansion of health insurance coverage in 2006. It required uninsured people to buy private policies and subsidized the purchase of insurance by the poor. The experiment became the template for a controversial, sweeping national expansion of health insurance that took effect in 2014.

But many changes are also occurring in emerging market and developing economies:

China: Shanghai, the nation’s major commercial city, undertook multipronged health care reform to reduce out-of-pocket health expenditures and improve health at lower cost (Cheng, 2013). For example, Shanghai’s community health clinics were offering residents 1,000 drugs under an essential drugs list—even before China embarked on national health reform in 2009, which made 307 essential drugs available to everyone in the country. The city may have China’s most advanced and integrated health information technology system, with all hospitals and doctors linked to patients’ medical records. That helps regulators monitor physician behavior, control costs, and ultimately improve health outcomes. The city is also at the forefront of developing an integrated delivery system across primary, secondary, and tertiary care. China’s other provinces are watching Shanghai’s actions closely.

Colombia: In Medellin, the second largest city in the South American nation, the government started a unified health provision network intended to reduce disparity in health care quality across the city (Guerrero and others, 2014).

Pakistan: In Punjab province, the government enacted a performance-based resource allocation model designed to clearly link a district’s funding to its health needs. Under the model, each of Punjab’s districts automatically receives 70 percent of its base allocation. To claim the remaining 30 percent a district must improve performance according to defined indicators, such as the proportion of babies delivered at a health facility or by a skilled birth attendant and the proportion of fully immunized children ages 18 to 30 months. The performance-based approach gives Punjab’s districts a clear incentive to improve health outcomes.

Brazil: The city of São Paulo runs the Agita São Paulo program, which promotes an active lifestyle through its message that 30 minutes of physical activity a day is an achievable and pleasurable health goal. São Paulo also holds mega-events to encourage people to change their behavior and improve overall population wellness. The campaigns were replicated by many other Brazilian cities (PAHO, 2011).

The push from above

But even as spending and innovation devolve to regional governments, national governments play a critical role in overseeing and directing the subnational entities and leveraging the funds that central governments transfer to them to support their health activities. Central governments can decide how to transfer funds to regional governments or pay health care providers to spur better performance in states or provinces and at even lower levels, such as municipalities.

In Rwanda, for example, the national government initiated incentive payments to subnational public and nonprofit faith-based providers, among others. The payments were conditioned on improvements in the amount of services and the quality of care provided to HIV/AIDS patients and mothers and children. The payments were approved on the basis of independent and representative audits of performance reports. As a result of the program, child nutrition improved significantly and provision of health care services increased by 20 percent (Gertler and Vermeersch, 2013).

In Argentina, the federal government uses incentives to induce the nation’s provinces to improve birth outcomes. The national government bases the incentive on enrollment of uninsured families in its Plan Nacer program, reductions in newborn deaths, and provision of quality prenatal care. The program reimburses provinces $5 a month on a per capita basis for each person enrolled and an additional $3 a month for reaching targets such as improved birth weight and vaccination coverage. That is, 60 percent of the reward is based on the number of people enrolled in the program and 40 percent on improved health coverage and outcomes. The result was a 22 percent decline in neonatal mortality between 2004 and 2008 (Gertler, Giovagnoli, and Martinez, 2014).

India’s national health insurance program for the poor, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), set up incentives for the nation’s states to buy in to the program. In each state, private insurance companies compete annually, on a district-by-district basis. A designated agency in each state chooses the most competitive and best-value premium for each district. Then, for each person enrolled, the states pay 25 percent of the premium and the central government pays the rest. There is no payment for performance. The district-level insurers are motivated to enroll as many people as they wish to maximize revenue. The program, which began in 2007, now covers more than a 100 million people with a relatively generous package for hospitalization. Early results suggest that fewer people have been impoverished because of out-of-pocket health payments (La Forgia and Nagpal, 2012). RSBY is relatively inexpensive and accounts for just a fraction of all public spending for health in India.

The capacity conundrum

Still, despite the promise of decentralization, there are serious challenges to moving government functions and expenditure responsibilities to the subnational level. Even when regional governments have great decision-making power, the state or province may have trouble following through because of little administrative capacity or lack of accountability—often both.

In Mexico, for example, where most health spending occurs at the regional or local level, the federal government tried to measure the performance of the nation’s states against benchmarks on such health interventions as early breast cancer detection and treatment (Lozano and others, 2006). Yet in some cases, states discontinued their reporting and the federal government ceased publication after only one round of benchmarking.

In many settings, increasing subnational responsibility and spending is associated with large differences in the standard of care, equity, and outcomes between wealthier and poorer regions in a country. There are many reasons for these gaps: differences in population characteristics, such as age, income, and underlying general health, risks, and behavior; a different revenue base; and local investment priorities. These gaps occur in advanced economies too. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service’s 2011 NHS Atlas of Variation revealed large differences in health services according to where people live.

In India, lower-performing and poorer states in the north-central belt, such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, lack administrative capacity and have difficulty spending the funds allocated to them by the central government. The ability to spend centrally allocated health funds ranges from 42 percent (Uttar Pradesh) to 89 percent (Maharashtra).

The differences in regional provision of health services—the result of varying resources and priorities—means that without policies to ensure portability of health benefits from one state or province to another, families that move within a country can find themselves without health coverage. In China, people’s ability to receive health care is tied to the region in which their household is registered (Roberts, 2012).

In some cases, functions that should be performed at the national level have been delegated to regional bodies with deleterious effects. Taxes aimed at improving health, such as on tobacco or alcohol; disease surveillance; and emergency response and risk pooling for expensive and rare diseases often make more sense at the national level, for example. A single case of a high-cost, rare disease can quickly bankrupt a local health system barring appropriate financial risk-sharing mechanisms. A rapidly growing epidemic that requires an all-country control response—for example, the recent outbreak of the Ebola virus in parts of west Africa (where public spending for health already is extremely low) can easily overwhelm local authorities.

In general, public health functions—such as vaccination and preventive services that are not profitable due to lack of demand—get short shrift both nationally and subnationally. Regional and local governments in some countries have reorganized their health departments in ways that reinforce a bias toward medicine (the treatment of diseases and conditions) and neglect public health, which focuses on preventing disease and maintaining a healthy population. In India, only the state of Tamil Nadu did not merge its health department unit focused on public health with the medical department. Perhaps as a result of this focus on prevention, Tamil Nadu’s health outcomes are among the best among the Indian states, whereas it ranks among the lowest in health care spending.

Rarely are policy challenges simple to solve; instead multiple solutions and attempts are needed. Policymakers can benefit greatly by adopting an attitude that fosters experimentation and learning. But experimentation, innovation, and learning are technically difficult and resource intensive and often threaten long-held ideas and entrenched interests.

In some countries, experimentation and innovation are led by states and provinces, and some have sought to institutionalize experimentation. In the United States, the Innovation Center at the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services facilitates systematic development of solutions to address low value and high cost in the U.S. health system. By ensuring funding for a 10-year period and with independence from the payer, Medicare and Medicaid, the Innovation Center buffers the usual disincentives and risks of innovation. The center has piloted a range of new models and approaches, including accountable care organizations and medical homes that aim to share financial risks between insurers and providers to encourage better coordination of patient care while reducing costs. Medicaid, the federal-state program to provide health services to the poor, allows for considerable variation among U.S. states in terms of coverage. With the Innovation Center’s financial and technical support, states can experiment with models tailored to their needs.

China experiments

Institutional experimentation is not limited to the United States and other high-income countries. China has historically experimented, usually starting on a small scale, in a few of its roughly 2,800 counties. Its flagship rural health insurance program, the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), was tried in a few counties before it was expanded nationally in 2003. The NCMS essentially offered basic health insurance for rural residents, who were paying largely out of pocket for health care.

In South Africa, the federal government has encouraged pilot projects for health insurance in 11 of its 54 districts, with the intention of adopting a national health insurance scheme to complement the existing public system of health facilities. Yet the pilots showed lack of technical capacity in the districts and insufficient technical assistance from the central government. No major initiatives for national health insurance have been announced since the pilots.

International donors can play a role in fostering experimentation at the subnational level. For example, the World Bank and GIZ, the German government’s development agency, provided significant technical support to India’s RSBY. The World Bank lends to state and provincial governments—in 2008 ranging from 10 percent of its total country lending to Mexico to more than 60 percent in countries such as India and Pakistan (World Bank, 2009). But these operations require a sovereign guarantee, which may or may not facilitate innovation in the subnational entities that can service debt. Subnational governments are theoretically eligible but have only rarely been recipients of grant support from public-private partnerships such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and GAVI, The Vaccine Alliance, which seeks to foster public health by subsidizing vaccinations and immunizations. If global health funders pay more attention to subnational governments, more creative approaches may yield or leverage greater health gains.

Health systems are increasingly local, and that should mean a change in how national and international policymakers approach issues of financing, fiscal transfers, and payment and provision policies. At a minimum, there should be greater attention to the ways subnational governments spend on health and how incentives for performance can cascade from central governments to states.

The health promise of more local power can only be made real if policy is aligned at all levels for better health system performance. ■

Victoria Fan is an Assistant Professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and a Research Fellow at the Center for Global Development, and Amanda Glassman is Director of Global Health Policy at the Center for Global Development.

References

Cheng, Tsung-Mei, 2013, “Explaining Shanghai’s Health Care Reforms, Successes, and Challenges,” Health Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 12, pp. 2199–204.

Fan, Victoria, and William D. Savedoff, 2014, “The Health Financing Transition: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Evidence,” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 105 (March), pp. 112–21.

Gertler, Paul, and Christel Vermeersch, 2013, “Using Performance Incentives to Improve Medical Care Productivity and Health Outcomes,” NBER Working Paper No. 19046 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research).

Gertler, Paul, Paula Giovagnoli, and Sebastian Martinez, 2014, “Rewarding Provider Performance to Enable a Healthy Start to Life: Evidence from Argentina’s Plan Nacer,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6884 (Washington).

Guerrero, Ramiro, Sergio Prada, Dov Chernichovsky, and Juan Urriago, 2014, “La Doble DescentralizaciÓn en el Sector Salud: EvaluaciÓn y Alternativas de Pol?tica Pública,” PROESA Report” (Cali, Colombia: Icesi University).

La Forgia, Gerard, and Somil Nagpal, 2012, “Government-Sponsored Health Insurance in India: Are You Covered?” World Bank Policy Note 72238 (Washington).

Langevin, Mark S., 2012, Brazil’s Healthcare System: Towards Reform? (Washington: BrazilWorks).

Lozano, Rafael, and others, 2006, “Benchmarking of Performance of Mexican States with Effective Coverage,” The Lancet, Vol. 368, No. 9548, pp. 1729–41.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), 2011, “Non-Communicable Diseases in the Americas: Cost-Effective Interventions for Prevention and Control,” Issue Brief (Washington).

Roberts, Dexter, 2012, “China May Finally Let Its People Move More Freely,” Business Week, March 15.

World Bank, 2009, “World Bank Engagement at the State Level: The Cases of Brazil, India, Nigeria, and Russia,” Independent Evaluation Group Report (Washington).