Dragon among the Iguanas

Finance & Development, December 2014, Vol. 51, No. 4

China’s economic and financial relationship with Latin America is increasingly important to the region

During a visit to Latin America in July 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping described the relationship between his country and the region as a “community of shared destiny.” But China is the one that seems to be shaping that destiny.

With the opening of China’s economy following its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the country has rapidly assumed a leading role in trade and foreign direct investment in the global economy. In 2012, it became the largest trading nation in the world, and in 2013 it became the second largest recipient of foreign direct investment after the United States and the third largest source of outward investment after the United States and Japan.

As part of its enormous expansion in global trade and investment activity since the turn of the century, China has significantly increased its economic and financial ties with Latin America. These initiatives by China have not been unique to Latin America; they are part of China’s more general “going out” strategy to establish trade and financial links with a number of developing areas of the south—in Africa and central and southeast Asia, as well as in Latin America.

The importance of this growing South-South relationship for China and Brazil was also manifest during Xi’s 2014 visit, when new lending arrangements for developing economies by the BRICS alliance—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—were formalized in Fortaleza, Brazil.

Closer ties

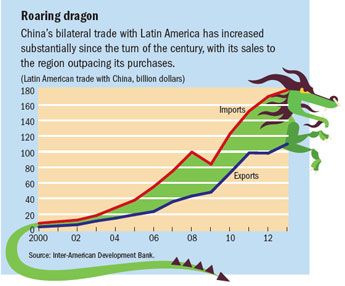

Bilateral trade between China and Latin America has grown exponentially since the early 2000s—from $12 billion in 2000 to $289 billion in 2013 (see chart). While there has been a growing imbalance between the two trading partners in favor of China over this period, this bilateral trade has also been asymmetrical in that China is a much more important trading partner for Latin America than the other way around. China is now the second largest source of Latin America’s imports (after the United States) and the third largest destination of its exports (after the United States and the European Union).

Latin America’s exports to China are almost entirely primary commodities (hydrocarbons, copper, iron ore, soybeans). China’s demand for these goods is one reason for the significant terms-of-trade gains Latin America enjoyed in the five years before the 2008–09 global financial crisis. These gains and the attendant growth in export volumes provided a significant boost to the region’s real GDP and income growth over that of the preceding decade.

China’s imports from Latin America reflect the country’s substantial demand for raw materials to support development. Its imports from the region are highly concentrated, coming primarily from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Venezuela. China has become a major export partner for these countries. However, China’s imports of raw materials and intermediate goods are well diversified. It also buys from African, Asian, and North American suppliers. An exception is copper, with 55 percent of its supply coming from the Latin American region (of which 30 percent is from Chile).

China’s exports to Latin America, in turn, have been mainly manufactured goods, mimicking the historical pattern of interindustrial trade between countries of the north and south. There have, however, been some notable exceptions to the traditional exchange of raw materials for manufactured goods, the most important example being the recent purchase by China of jet aircraft from Brazil’s Embraer Corporation.

More generally, however, China’s significant administrative barriers have inhibited Latin American exports of manufactured goods to China, as have the high transportation costs compared with markets in the Western Hemisphere. In addition, the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has noted concern in Argentina and Brazil about possible Chinese dumping of simple manufactured exports such as steel, textiles, and domestic appliances.

Lending and investment

Financial linkages between China and Latin America have also increased significantly since the middle of the past decade, although China’s lending and investment activity has been much smaller in absolute terms than its imports from the region. Since 2005, total loan commitments from the China Development Bank and the China Exim Bank to Latin America amount to nearly $100 billion, according to the Inter-American Dialogue, based in Washington, D.C.

Lending by China in 2010 was roughly equivalent to that by the World Bank, Inter-American Bank, and Export-Import Bank of the United States combined, but it has since declined. Unlike lending from these agencies, much of the financing from China was allocated to countries such as Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela with limited access to other official or private funding. Venezuela, which accounts for roughly half of the region’s total borrowing from China, expects to make a substantial share of its loan repayments in kind, through oil exports. China has placed few, if any, conditions on its lending to the region, which has been allocated to a variety of infrastructure projects.

During his recent tour of Latin America, Xi announced $35 billion in new lending facilities to finance additional infrastructure and development projects of interest to both China and recipient countries in Latin America. A new joint forum comprising China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), which was also announced during the Chinese president’s visit, will manage most of this funding. The forum is intended to promote cooperation between the two partners on a wider range of issues than economic and financial ties.

One important infrastructure project under discussion among China, Brazil, and Peru is the construction of a transcontinental railway in South America, which would be the first regional project of this kind. Discussions have also taken place between a private Chinese investor and the Nicaraguan government regarding a transoceanic canal through Nicaragua.

Foreign direct investment from China closely mirrors its pattern of imports and is heavily oriented toward the expansion of natural resource exploitation in Latin America (copper and iron ore mining, hydrocarbon exploration, soybean production). Argentina, Brazil, and Peru have been the largest recipients of China’s foreign direct investment, which amounted to about $32 billion during 2010–12. Chinese firms have a particularly strong pipeline of projects in Peru to develop that country’s copper mining resources, amounting to $20 billion. This exceeds investments by U.S. and Canadian firms combined, which until now have been the dominant investors in Peru’s copper sector.

A substantial share of China’s foreign direct investment to Latin America is channeled through the British Virgin and Cayman Islands, according to statistics from the UN Commission on Trade and Development. However, the eventual destination of these flows cannot be clearly identified. Excluding flows channeled through these offshore financial centers, foreign direct investment from China amounted to only about 5 to 6 percent of total inward investment to Latin America in recent years, though this share is expected to increase.

Not all good news

Latin America’s economic and financial relations with China have provided significant gains for the region in recent years in the form of export expansion and foreign capital inflows. But there might be negative repercussions over the longer term.

One problem relates to the so-called recommodification of the region’s exports. The share of raw materials in Latin America’s exports had fallen from about 52 percent in the early 1980s to a low of 27 percent in the late 1990s, but had risen to more than 50 percent just before the global financial crisis. Latin America’s historical dependence on natural resource–based exports has been a problem for the region, exposing it to terms-of-trade volatility and weakening the competitiveness of its manufacturing sector through exchange rate fluctuations.

The phenomenon of recommodification has been reinforced by the recent increase in Latin America’s imports of manufactured goods from China, many of which compete directly with manufacturing in the region, which is oriented toward both domestic and regional markets. This, in turn, could dampen demand for products of other manufacturing and nonmanufacturing sectors that are upstream suppliers for these industries. Issues of dumping, noted earlier, only heighten these concerns. Given the nature of China’s exports to the region, there is little or no gain from their contribution to the technological upgrading of the region’s production.

Manufacturing as a share of regional GDP declined from 25 percent in 1980 to 21 percent in 2000 and to 15 percent in 2010, according to data compiled by ECLAC. Over the same period, manufacturing within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations region and in China rose to about 40 percent of GDP. One recent study concluded that China’s exports of low-cost manufactures to Latin America and third markets have significantly eroded Latin America’s competitiveness in those markets, which has put a major brake on the expansion of the region’s industrial base (Gallagher and Porzecanski, 2010).

In addition to competition from China’s manufactured exports, Latin America is contending with recent softening in its external terms of trade and weaker global demand for its commodities, partly related to China’s rebalancing away from investment toward domestic consumption (see “Sino Shift” in the June 2014 issue of F&D). This development, in turn, has reexposed the region to the prospect of significantly lower growth, according to the IMF’s recent World Economic Outlook forecasts.

Against these headwinds, the region faces some of the same challenges for its long-term development that hindered sustained growth before its engagement with China. One hurdle is expansion and upgrading of its transportation, shipping, and power generation infrastructure beyond what is supported by China. In recent years, Latin America has underinvested in infrastructure, with public investment of about 2 percent of GDP a year over the past decade. This is less than half the annual rate spent by the high-growth economies of east Asia.

One important area of infrastructure development that has become a critical factor in export competitiveness is the quality of a country’s trade facilitation services—customs clearance and transit procedures, communication facilities, trade finance, and arrangements for new business registration. With the growing importance of global value chains in international trade, these services are becoming indispensable. South America participates little in global value chains—much less than east Asia, for example. The latter region has been called “factory Asia” thanks to the dense network of cross-border manufacturing linkages that underpins its export dynamism, in which China plays a key role.

A second critical area for Latin America’s future development is technological innovation, which is essential for the upgrading of its manufacturing base and improvements in labor productivity. Export diversification linked to an increase in the technological sophistication of manufactured goods is a key factor in promoting high rates of economic growth. International surveys by the World Economic Forum show that private enterprise in Latin America generally falls short—compared with east Asia—in business operations’ technological capability, as reflected in outlays for research and development, installed capacity for innovation, and the number of patents issued.

Along with these areas for improvement, Latin American governments should take advantage of the new joint China-CELAC Forum to seek ways to diversify the region’s export trade and increase its foreign direct investment with China. The rebalancing of China’s economy, noted earlier, should present opportunities for growth in the region’s manufactured exports given the anticipated strengthening of the renminbi and a rise in domestic wages and consumption. Over time, such efforts should enable Latin America to benefit further from its economic and financial links with China, which has become one of its key partners in the global economy.

President Xi’s 2014 visit to Latin America is tangible evidence that this development is of keen strategic interest to China as well. ■

Anthony Elson teaches at Duke and Johns Hopkins Universities and is the author of Globalization and Development: Why East Asia Surged Ahead and Latin America Fell Behind.

Reference

Gallagher, Kevin, and Roberto Porzecanski, 2010, Dragon in the Room: China and the Future of Latin American Industrialization (Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press).