Picture This

Sound Money

Finance & Development, September 2014, Vol. 51, No. 3

Live music’s debut as a big export earner

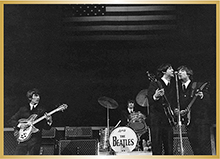

In February 2014 a musical celebration in a drab, cavernous warehouse in central Washington, D.C., marked the first U.S. concert played by British rock band The Beatles in the same building exactly 50 years earlier. But this year’s event was also the 50th anniversary of live music’s debut as a serious foreign exchange earner.

In 1964, major exchange rates were fixed under the Bretton Woods system introduced—along with the IMF and the World Bank—in 1944. The IMF was formed to help keep these exchange rates stable, and the major economies also used exchange controls to maintain their currencies’ value. These controls meant that corporations and private citizens had to have government permission to convert their domestic money to foreign currency and could do so only within legal limits.

Preserve that parity

Maintaining fixed exchange rates placed enormous importance on the major economies’ trade balances, since the hard currency earned by exports or spent on imports effectively set exchange rate levels. Britain’s pound sterling was under sustained downward pressure in the mid-1960s from a persistently adverse trade balance, and the U.K. government of the day was fighting to preserve the pound’s parity of $2.80 and avoid the ignominy of formal devaluation within the Bretton Woods system.

Magical minstrels

Along came The Beatles—mere minstrels to many, but to the U.K. government a magical machine for printing U.S. dollars. Major live popular musical acts in the mid-1960s typically earned only domestic currency. U.S. singer Elvis Presley, for example, never performed outside North America and Hawaii, and his concert earnings were all in U.S. dollars apart from four appearances in Canada.

Dollars, deutsche marks, yen

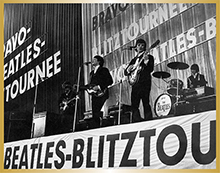

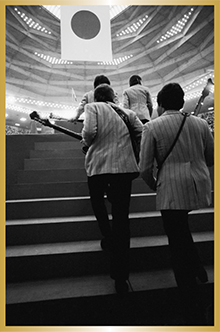

The Beatles by contrast posted world-record dollar-denominated concert receipts from appearances during U.S. tours in 1964, 1965, and 1966. Media reports said they earned a net $650 a second in today’s dollars performing live in 1965. Furthermore, in 1966 the band also embarked on concert tours of Germany and Japan that raked in massive performance fees denominated in deutsche marks and yen. At the very same time, sterling was under increasing pressure from a U.K. consumption boom that was boosting imports and a prolonged seamen’s strike that was blocking exports.

Tune power

By cashing in their hard-currency appearance fees, The Beatles joined an elite category of British “invisible” exporters: commercial enterprises that earned foreign currency not from the manufacture and transshipment of visible, physical goods, but from invisible credits and receipts. The U.K. current account in the mid-1960s would have been in constant deficit absent traditional British invisible exports at the time arising from financial services, insurance, patents, and copyrights. To this ledger The Beatles now added earnings from their own invisibles: ticket sales, appearance fees, music royalties, merchandise licensing, and performance rights.

Exporters award

Britain’s prime minister in the mid-1960s was an award-winning Oxford-educated economist, Harold Wilson, whose keen professional eye quickly noted The Beatles’ contribution to the balance of payments as his government struggled to defend sterling.  In November 1965 Wilson duly decorated the band as Members of the Order of the British Empire, a national honor usually accorded leading industrialists, entrepreneurs, and inventors.

In November 1965 Wilson duly decorated the band as Members of the Order of the British Empire, a national honor usually accorded leading industrialists, entrepreneurs, and inventors.

Sterling’s secret weapon

As attendance at Beatles concerts soared and venues grew increasingly chaotic, public order was threatened and the band stopped appearing live in concert altogether in August 1966. A year later, sterling was devalued to $2.40, and the United Kingdom requested loans from the IMF in 1967 and 1969. Today, key exchange rates float, and major governments no longer need to defend fixed parity with exchange controls or scramble for invisible exports to bolster sagging trade balances. But 50 years ago, The Beatles’ historic hard-currency earnings were Britain’s secret weapon in a three-year effort to fend off devaluation.