A Turn to Asia

Finance & Development, June 2014, Vol. 51, No. 2

To sustain its rapidly rising prosperity, Australia should seize on the changing export opportunities in its nearest neighbors

A STRONG increase in export prices and a boom in mining investment supported buoyant income growth and rising living standards in Australia over the past decade. Now, as mining investment begins to slow, Australia needs to generate higher productivity and broaden its export base to sustain that rapid improvement in prosperity.

Over the past decade a mining investment boom transformed Australia’s economy into one that is more resource intensive than before and increased its export links with Asia. Australia benefited from Asia’s rapid industrialization and urbanization, especially in China, which led to higher demand for products required for construction and other investment and led to sharply rising global commodity prices from the early 2000s through 2011.

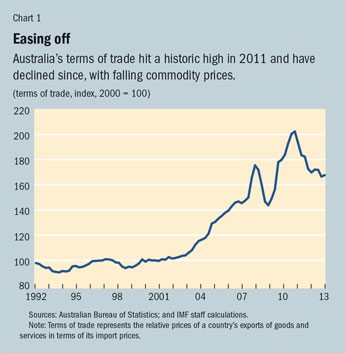

Increased exports of commodities, whose prices can be volatile, have also made the Australian economy more sensitive to changes in the terms of trade—that is, the relative price of exports in terms of imports (see Chart 1). Because of high export prices for coal and iron ore, which started rising in the early 2000s, Australia’s terms of trade reached a historic high in 2011. Since then, as the supply of commodities increased, prices have softened and Australia’s terms of trade weakened, lowering income and reducing tax revenues.

Meeting demand

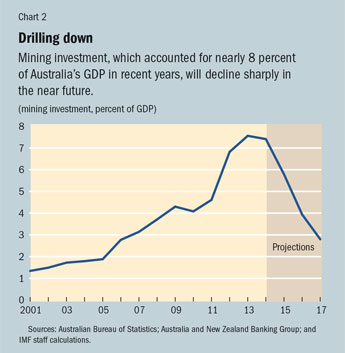

When commodity prices began to rise a decade ago, Australia, like other resource producers, ramped up mining investment and increased output. The country’s mining investment rose from about 2 percent of GDP in 2002 to about 8 percent in 2013 (Arsov, Shanahan, and Williams, 2013). Investment was mainly in coal and iron ore early on, but more recently, liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects have increased to meet rising global demand for energy.

The mining investment boom has helped Australia’s economy grow for 23 consecutive years—even during the recent global economic crisis. Between 2000 and 2012, real (after-inflation) incomes grew an average 2.5 percent a year per capita.

And mining will remain an important part of Australia’s economy. The country’s resources are diverse and plentiful and Australia is a low-cost and very competitive producer. In 2011 Australia had the world’s largest reserves of gold, iron ore, nickel, rutile, and zircon. It also has bountiful reserves of a number of other minerals, including black coal (Australian Government, 2013), and is the world’s third-largest LNG exporter (EIA, 2013).

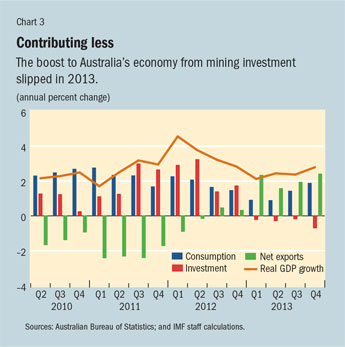

Still, the future is uncertain. Over the next five years the export volume of iron ore and coal will increase as investment projects come onstream (mining export volume could rise by more than 30 percent in the next five years). But their prices are likely to decline as the global supply of bulk commodities rises. At the same time the boost to the economy from mining investment will ebb (see Chart 2). Mining-related investment, which accounted for almost half of GDP growth in recent years, is expected to drop sharply in the near term (see Chart 3).

To maintain strong growth over the longer run, then, the economy will need a pickup in productivity, higher nonmining investment, and manufacturing and services exports. The question for Australia is how to move to broader-based growth. The answer may lie partly in Australia’s export links with Asia and whether its domestically oriented service sector—which accounts for 71 percent of its GDP and a large share of employment—can find and expand markets abroad.

Turning to Asia

Over the next decade Asia is expected to become an even more important engine of world growth than it is now. Its demand patterns are changing as the region’s middle class expands rapidly and consumption increases. According to the U.S. National Intelligence Council (2012), by 2030, two-thirds of the world’s middle class will live in Asia. Asia’s emerging markets are expected to increase their share of world GDP (measured at purchasing power parity) from 30 percent today to 41 percent in 2023. As their financial markets get bigger and offer more services, emerging Asia’s banks are expected to increase their share of global banking assets from 18 percent today to 31 percent in 2023.

The shift in global activity to Asia will ease the “tyranny of distance”—the high costs Australia traditionally faced as an exporter far from the major economies of Europe and North America. The share of world output within roughly 6,000 miles of Australia has more than doubled over the past 50 years to more than a third of global output and could rise to about half by 2025 (Australian Government, 2012). Because markets are closer, transportation and communication costs are lower, so Australia’s profitable export opportunities should expand. Moreover its potential markets should also grow because it trades with growing markets such as China, India, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

As Asia grows, industry and trade patterns are likely to shift. Many Asian economies are part of a multicountry production process called a value chain, in which final products are put together with inputs from various countries. As countries move up the value chain—that is, supply more technologically advanced inputs—they require a wider range of the kinds of sophisticated and niche products and services Australia can supply.

Moreover, Asia’s rapidly expanding middle class will have different tastes and demand will shift to a broader range of products and services. The demand for dairy products, for example, is already increasing. Demographic trends in Asia are also likely to be important. Some countries, such as China, Japan, and Korea, have rapidly aging populations, which will increase demand for age-related goods and services such as health care. Other countries with rapidly expanding workforces, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, have growing infrastructure needs, which could increase demand for Australia’s traditional export commodities.

Australia is already an Asia-oriented exporter. China, India, Japan, and other Asian neighbors account for more than 70 percent of Australia’s merchandise exports. The potential for growth lies in trade in services. Chinese and Indian markets for Australia’s service exports increased fivefold over the past decade. The recent introduction of direct trading of Australian dollars and Chinese renminbi should facilitate commerce between the two countries.

Seizing opportunities

Australia’s economy, with its growing and highly skilled workforce and large service sector, is well positioned to offer trade in services to the emerging Asian middle class. A number of service sectors are potentially major sources of foreign income and contributors to economic growth (Australian Government, 2013). These include:

Higher education: Australia has the world’s highest proportion of foreign students in its universities, is the third most popular destination for overseas students after the United States and the United Kingdom (OECD, 2013), and is already a leading and ever more popular destination for Asian students. As Asian prosperity rises, the number of students from Asia should increase as well.

Tourism: Asia is now Australia’s biggest single source of tourists, and people from that region represent about 40 percent of foreign visitors. Even so, Asian tourists are a far smaller share of Australia’s foreign visitors than in most Asian countries (BFA, 2012). More than 70 percent of arrivals in China, Hong Kong SAR, Japan, Malaysia, Korea, and Taiwan Province of China come from Asia.

Business services: Providers of professional services, engineering, design, and especially mining-related services are in a good position to sell their expertise to Asian markets.

Health care: Australia is well placed when it comes to pharmaceutical exports and well equipped to deliver professional training, including in the treatment of cancer and heart and liver disease (KPMG, 2012). Australian universities have developed medical research partnerships with a number of their Asian counterparts.

Financial services: Australia’s direct financial market ties with Asia have developed more slowly than other relationships. Australian banks do relatively little business with Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries—about 20 percent of their total foreign business—although ASEAN economies are now Australia’s largest trading partners. There is potential for further financial integration, given the trade links.

Australia’s prowess in the traditional areas of mining and mining support industries and agriculture and agribusiness will remain very important. The mining support industry often stimulates exports from other sectors, such as construction, manufacturing and mining services, and technology, which are needed to build production capacity. In agriculture, exports of specialized products have been growing—for example, wine sales to China are five times what they were half a decade ago. Agricultural innovation and technology and food security, already important areas in Australia, are of growing importance to Asian economies as well.

Because the country concentrates so much on resource exports, Australia’s terms of trade will deteriorate further as commodity prices decline. But its floating exchange rate can help buffer the effect of declining commodity prices because the Australian dollar should depreciate when the terms of trade deteriorate. That will effectively lower the price and increase the competitiveness of other tradable goods and services. If the exchange rate moves broadly in line with the terms of trade, as it has in the past, it would help Australia rebalance its economy.

But it may take more than a rise in noncommodity exports to keep living standards growing at the pace of the past decade. Australia needs to generate gains in overall productivity—a difficult task.

Because Australia undertook large-scale reform of product, labor, and capital markets during the 1980s and 1990s, there is little the government can do now that will result in quick gains. But the government is building on the earlier reforms, by encouraging investment in nonmining sectors and by developing highway and freight rail projects in urban and regional areas to remove infrastructure bottlenecks. The government is enlisting the private sector to find new ways to finance infrastructure development and aims to help cut business costs through deregulation and a thorough review of competition laws to identify areas for reform. A review of the financial services sector is already under way, and the government has committed to an examination of the tax system as

well. ■

References

Arsov, Ivailo, Ben Shanahan, and Thomas Williams, 2013, “Funding the Australian Resources Investment Boom,” Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin (March), pp. 51–61.

Australian Government, 2012, “Australia in the Asian Century,” White Paper (Canberra).

———, 2013, “Australia’s Identified Mineral Resources 2012,” Geoscience Australia Report (Canberra).

The Boao Forum for Asia (BFA) Progress of Asian Economic Integration, 2012, Annual Report (Beijing).

KPMG, 2012 “Australia in the Asian Century: Opportunities and Challenges” (Australia, various locations).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2013, “ Education at a Glance,” Australia Country Note (Paris).

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2013, “Australia” (Washington).

U.S. National Intelligence Council (NIC), 2012, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds (Washington).