A Long Shadow over Growth

Finance & Development, March 2014, Vol. 51, No. 1

Helge Berger and Martin Schindler

Conquering unemployment and boosting growth is the number one priority in Europe today

Even if the European economy were sailing along at full capacity—and it clearly is not—some people would be looking for jobs. As new and innovative firms make their way into the marketplace and less productive firms retreat, employees are on the move as well, and finding a new job will always take some time. Some unemployment is therefore part and parcel of a healthy and growing economy.

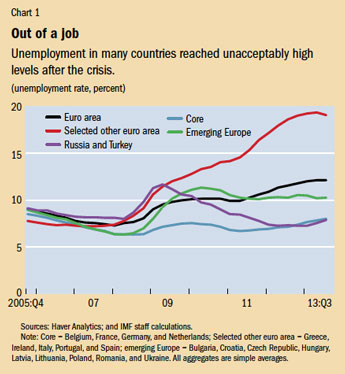

But these are not normal times: since the beginning of the European debt crisis, euro area unemployment has risen to nearly 20 million people. At the end of 2013, this meant about 12 percent of those looking for work remained without a job, about one and a half times the level before the crisis (see Chart 1). What is worse, an increasing share of those seeking employment have been out of work for more than one year. The latest available numbers suggest that nearly half of Europe’s unemployment is long term.

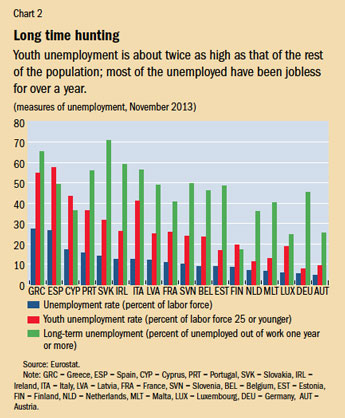

Unemployment on this scale is worrisome. The sacrifice and hardship that come with being out of work for a long time have affected many European families. To make matters worse, the unemployment crisis also threatens to cast a long shadow over Europe’s ability to grow in the future. Much of the rise in unemployment has been concentrated among vulnerable groups, including the less educated and the young: at the end of 2013, more than half of those below age 25 looking for work in Spain and Greece were without a job (see Chart 2). The comparable figure is over one-third in Italy and Portugal, about a quarter in Ireland, and nearly one-quarter on average in Europe. Numbers like these raise the specter of a lost generation.

The repercussions of being unemployed at a young age are severe. It means that those who are well trained cannot put their skills to work and, in an application of the “use it or lose it” principle, may lose those skills, while those with less education are missing out on crucial on-the-job training. All of these could have lasting consequences and set young people off on a permanently lower earnings path, risking entrenchment of already rising income inequality.

But the scarring effects of unemployment at a young age extend well beyond the economic sphere: many unemployed people adjust their life decisions accordingly, deferring marriage and child rearing or leaving home to seek employment abroad. While migration supports macroeconomic adjustment when other mechanisms fail, it can come at a cost for those who have to move: cultural change, the need to learn a new language, and a lack of recognition of degrees and training can mean that highly skilled workers are employed in low-skill jobs. The tale of highly trained foreign scientists driving cabs in Berlin or Stockholm is not far from reality.

A two-way street

There is clearly a need for action: unemployment is at tragic, unacceptable levels in many countries and threatens to hold back growth in the European economy for years to come. But while the call to policymakers is loud and clear, putting people back to work is far from simple. A new IMF book, Jobs and Growth: Supporting the European Recovery, based on extensive analysis by IMF staff members, provides a road map for policymakers on how to answer this call for action.

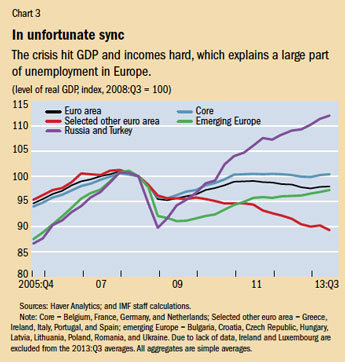

Getting economic growth going must be the priority. A harsh lesson reaffirmed by the crisis is that the relationship between jobs and growth is a two-way street. Mass unemployment often translates into weak consumption and fewer incentives to invest, so growth is depressed and firms have little incentive to hire. At the same time, securing higher levels of growth would create employment and support private demand. This link between unemployment and growth certainly applies to Europe today (see Chart 3). Thus, the first and most effective way to address unemployment is to get growth going again.

But how can countries get this done? There are no quick or easy fixes. Raising and sustaining growth is a complex and multifaceted challenge that requires action on many fronts and over different time horizons. Indeed, while there is a sense that the worst of the crisis may be behind us, growth rates and output levels remain below precrisis levels. Annual growth in Europe is projected to average just 1.6 percent between 2013 and 2017, barely half the 2.6 percent achieved in the five years before the crisis (IMF, 2014). Thus, in the near term, there is a need for continued monetary policy support and for fiscal consolidation to proceed gradually, where markets allow, to protect the recovery.

But just as urgent is steady progress in enhancing the euro area’s institutional framework, and putting in place the elements of a banking union would be an excellent place to start. The ability to undertake timely, effective, and low-cost resolution of ailing banks with access to common public resources—a common backstop—would help break the vicious cycle of mutually reinforcing distress in the banking and public sectors.

Progress on euro area institutions would also go a long way toward reducing the residual uncertainty of investors, who will have to trust that the crisis is finally over before they commit significant resources to the future. In addition, the medium-term work of strengthening public and private balance sheets has to start in earnest everywhere to reduce vulnerabilities. And there is little doubt that tackling long-standing weaknesses in labor and product markets is required to lay the foundation for lasting output and employment growth in Europe and to help realize the promise of the economic and monetary union for those in the euro area.

Crisis legacies

A lasting pickup in growth will remain out of reach, however, until the crisis’s balance sheet legacies are addressed. In many European countries, already high debt ratios among households and businesses worsened as a result of falling or negative income growth while property prices fell. Public sector debt also increased significantly during the recession. Given the slow pace of global demand, there is little hope that any of these sectors will simply grow out of their debt problems. The resulting pressure to deleverage—that is, to bring down debt by reducing household consumption, corporate investment, and government net spending—threatens to hamper the recovery.

That said, not all debt is created equal. Economists are still debating the link between debt and growth, but IMF research indicates that high levels of private sector debt may be particularly problematic. Indeed, while very high household and corporate debt tends to unambiguously lower growth—mostly because it creates vulnerabilities and reduces consumption and investment spending—there are indications that, where fiscal sustainability is not at risk, public sector debt on its own may be less detrimental. This suggests that by facilitating private sector deleveraging now, governments may be able to improve the conditions for self-sustained growth later on. Depending on country circumstances, policymakers may be able to do this by putting in place or reinforcing appropriate microstructures, such as effective insolvency frameworks—featuring, for example, fast and flexible personal and corporate bankruptcy proceedings—to help avoid lengthy periods of deleveraging and to protect growth.

Ultimately, of course, government debt will have to come down as well. History tells us that this is difficult, but not impossible to do even in a lower-growth environment. For example, in the early 1990s, Belgium, Denmark, and Iceland achieved debt reductions exceeding 30 percent of GDP, in spite of initially close to zero, or even negative, growth. Going forward, the trick is to reduce budget deficits gradually, where markets allow, with policies anchored by a durable commitment to sustaining fiscal consolidation over the medium term, and to make a strong effort to limit the impact of budget tightening on growth through smart design of revenue and expenditure measures. For example, cutting less productive spending, protecting public investment, and shifting the emphasis from direct to indirect taxes will help, and some countries may also have scope for additional privatization efforts. What is more, consolidation episodes can also provide a chance to implement growth-enhancing tax or subsidy reforms.

Laying the foundations

The opportunities for reforms that will help lift growth in the longer term are not limited to the fiscal realm. Country circumstances differ, but there are strong indications that truly ambitious structural reforms can make a significant difference for what economists call potential growth—countries’ capacity for sustainable income growth and employment—which, in turn will help households and firms strengthen their balance sheets. IMF research suggests that simultaneous reforms in product and labor markets carry the greatest promise for raising potential growth, although reform priorities and their optimal design will vary widely across countries. For example, measures to increase productivity in the German services sector, such as through strengthened competition and public investment in the energy and transportation industries, can help boost investment, incomes, and domestic demand, while further enhancing labor market flexibility in Spain can foster adjustment there. Elsewhere, many of the Balkan economies that are not members of the European Union (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia) need to address deep-rooted problems arising from a delayed transition process, poor investment climate, and the resulting low flows of foreign direct investment.

Comprehensive reform is a key to success—only partially addressing problems can actually make matters worse. The past two decades of piecemeal labor market reforms in many European economies illustrate this point. Although labor markets have become more flexible on average, reform efforts were in many cases partial and asymmetric—for example, reducing dismissal restrictions on temporary jobs but not on others. This often resulted, among other things, in split (or “dualized”) labor markets that work very differently for workers with permanent than for those with shorter-term contracts. Dual labor markets, combined with a lack of wage flexibility, especially at the lower end, can mean that firms under pressure to cut costs are forced to reduce employment if wages cannot adjust. Vulnerable groups, such as the low-skilled and the young, tend to be particularly affected by such outcomes, leading to fateful surges in youth unemployment in some European economies. As noted earlier, this can have grave social and economic consequences.

Taking advantage of changes

Addressing their structural weaknesses can also help countries benefit more from the export dynamics provided by global supply chains. Such links are gaining in importance as firms increasingly unbundle their production processes and take their activities where they find the right skills and factors of production. The examples of some eastern European economies, such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia, suggest that some of the same reform efforts that can help an economy grow will also advance its competitiveness and ability to attract foreign investment into higher-productivity export sectors, which in turn generates benefits for the economy as a whole. These dynamics may help explain the drop in Slovakia’s unemployment before the crisis. Among other things, increased supply-chain integration could also help address the widening divergences in intra–euro area current account balances that were observed prior to the crisis. Indeed, much of the recent reduction in current account deficits in the countries hit most by the crisis was triggered by the crisis itself—where jobs and growth are lacking, spending on domestic and imported goods and services tends to be weak. How much better it would be if these imbalances were resolved through faster export growth instead of shrinking imports and living standards.

Boosting jobs and growth in Europe is a difficult task. There are encouraging signs that the worst may finally be over, but the impact of the crisis will be felt for some time to come, and the challenges it has thrown at policymakers are immense. The good news is that there is a road map to chart the course to full recovery.

In the short term, policies to boost demand for goods and services, especially supportive monetary policy, can help protect the rebound, and completing the institutional infrastructure of the euro area—most pressingly toward a full banking union—will reduce uncertainty and the risk of future crises. There are also, where needed, options to address the crisis’s damage to household and corporate balance sheets, and a thorough reform effort can clear the structural obstacles to output and employment growth in the longer term.

Helge Berger is an Advisor, and Martin Schindler is a Senior Economist, both in the IMF’s European Department.

This article draws on research results summarized in a new book by the IMF’s European Department: Jobs and Growth: Supporting the European Recovery.

Reference

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2014, World Economic Outlook Update (Washington, January).