Who Let the Gini Out?

Finance & Development, December 2013, Vol. 50, No. 4

Davide Furceri and Prakash Loungani

Capital account liberalization and fiscal consolidation confer benefits but also lead to increased inequality

Income inequality is at historic highs. The richest 10 percent took home half of U.S. income in 2012, a division of spoils not seen in that country since the 1920s. In countries that belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, inequality increased more in the 3 years up to 2010 than in the preceding 12. The recent increases come on top of growing inequality for more than two decades in many advanced economies.

What explains this rise? A number of factors are at play (Milanovic, 2011). Technological change in recent decades has conferred an advantage on those adept at working with computers and information technology. Global supply chains have moved low-skill tasks out of advanced economies. Thus the demand for highly skilled workers in advanced economies has increased, raising their incomes relative to those less skilled.

Our recent research uncovered two other contributors to increased inequality. The first is the opening up of capital markets to foreign entry and competition, referred to as capital account liberalization. The second source is policy actions by governments to lower their budget deficits. Such actions are referred to as fiscal consolidation in economists’ jargon and, by their critics, as “austerity” policies.

These results do not imply that countries should not undertake capital account liberalization or fiscal consolidation. After all, such policy actions are not taken on a whim, but reflect an assessment that they will benefit the economy. What the research suggests is that these benefits should be weighed against their distributional impact. In many cases governments may have the flexibility to design the policy actions in a way that mitigates the distributional impact. IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde (2012) urges a “fiscal policy that focuses not only on efficiency, but also on equity, particularly on fairness in sharing the burden of adjustment, and on protecting the weak and vulnerable.”

Open to inequity

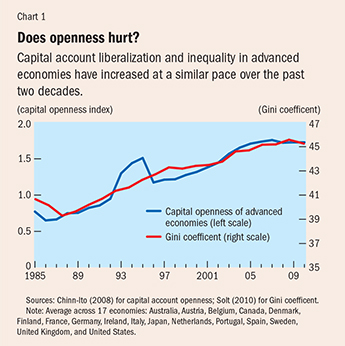

The past three decades have been associated with a steady decline in the number of restrictions that countries impose on cross-border financial transactions, as reported in the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions. An index of capital account openness constructed from these reports shows a solid increase—that is, restrictions on cross-border transactions have been steadily lifted. At the same time, there has been an increase in income inequality in advanced economies—as measured by the Gini coefficient, which takes the value zero if all income is equally shared within a country and 100 (or 1) if one person has all the income (see Chart 1).

To uncover whether there is a link between the two developments, we studied episodes of large changes in the index of capital account openness, which are likely to represent deliberate policy actions by governments to liberalize their financial sectors. Using this criterion, there were 58 episodes of large-scale capital account reform in 17 advanced economies.

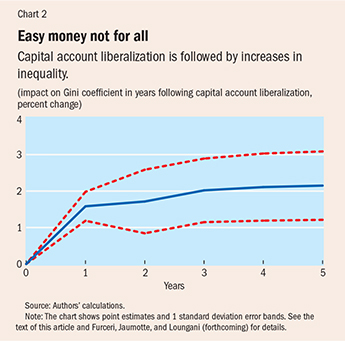

What happens to inequality in the aftermath of these episodes? The evidence is that, on average, capital account liberalization is followed by a significant and persistent increase in inequality. The Gini coefficient increases by about 1 percent a year after liberalization and by 2 percent after five years (see Chart 2).

The robustness of this result is documented extensively in our research (Furceri, Jaumotte, and Loungani, forthcoming). In particular, the impact of capital account liberalization on inequality holds even after the inclusion of myriad other determinants of inequality, such as output, openness to trade, changes in the size of government, changes in industrial structure, demographic changes, and regulation of product, labor, and credit markets.

There are many channels through which opening up the capital account can lead to higher inequality. For example, such liberalization allows financially constrained companies to borrow capital from abroad. If capital is more complementary to skilled workers, liberalization increases the relative demand for such workers, leading to higher inequality in incomes. Indeed, there is evidence that the impact of liberalization on wage inequality is greater in industries that are more dependent on external finance and where the complementarity between capital and skilled labor is higher (Larrain, 2013).

Who gets hurt?

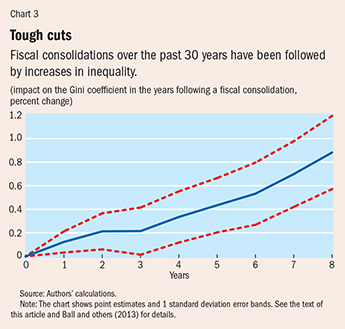

Fiscal consolidation—a combination of spending cuts and tax hikes to reduce the budget deficit—is a common feature of government actions. So history offers a good guide to studying the impact of these policies on inequality. Over the past 30 years, there were 173 episodes of fiscal consolidation in our sample of 17 advanced economies. On average across these episodes, policy actions reduced the budget deficit by about 1 percent of GDP.

There is clear evidence that the decline in budget deficits was followed by increases in inequality. The Gini coefficient increased by 0.2 percentage point two years following the fiscal consolidation and by nearly 1 percentage point after eight years (Chart 3).

One explanation for these results could be that while fiscal consolidations coincide with inequality, it is actually a third factor that is responsible for movements in both. For example, a recession or a slowdown could raise inequality and at the same time lead to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, thus raising the odds of a fiscal consolidation. However, the impact of fiscal consolidation on inequality holds even after controlling for the impacts of recessions and slowdowns. Other tests of the robustness of these results are reported in two recent IMF papers (Ball and others, 2013; Woo and others, 2013).

Fiscal consolidation can raise inequality through many channels. For instance, cuts in social benefits and in public sector wages and employment often associated with fiscal consolidation may disproportionately affect lower-income groups. The impact of fiscal consolidation on long-term unemployment is another possible channel, since long-term unemployment is likely to be associated with significant earnings losses (Morsy, 2011).

Policy lessons

Both capital account liberalization and fiscal consolidation confer benefits. The former allows domestic companies access to pools of foreign capital, and often—through foreign direct investment in particular—to the technology that comes with it. It also allows domestic savers to invest in assets outside their home country. If properly managed, this expansion of opportunities can be beneficial. Likewise, fiscal consolidation is generally undertaken with the aim of reducing government debt to safer levels. Lower debt in turn can help the economy by bringing down interest rates—and over time, with a lighter burden of interest payments on the debt, the government can also cut taxes.

However, at a time when rising inequality is a source of concern to many governments, weighing these benefits against the distributional effects is also important. Awareness of these effects might lead some governments to choose to design policy actions in a way that redresses the distributional impacts. For instance, greater resort to progressive taxes and the protection of social benefits for vulnerable groups can help counter some of the effect of fiscal consolidation on inequality. By promoting education and training for low- and middle-income workers, governments can also counter some of the forces behind the long-term rise in inequality. ■

Davide Furceri is an Economist and Prakash Loungani is an Advisor, both in the IMF’s Research Department.

References

Ball, Laurence, Davide Furceri, Daniel Leigh, and Prakash Loungani, 2013, “The Distributional Effects of Fiscal Consolidation,” IMF Working Paper 13/151 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Chinn, Menzie D., and Hiro Ito, 2008, “A New Measure of Financial Openness,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 309–22.

Furceri, Davide, Florence Jaumotte, and Prakash Loungani, forthcoming, “The Distributional Effects of Capital Account Liberalization,” IMF Working Paper (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Lagarde, Christine, 2012, op-ed, China Daily, December 28.

Larrain, Mauricio, 2013, “Capital Account Liberalization and Wage Inequality,” Columbia Business School Research Paper (New York: Columbia University).

Milanovic, Branko, 2011, “More or Less,” Finance & Development (September).

Morsy, Hanan, 2011, “Unemployed in Europe,” Finance & Development (September).

Solt, Frederick, 2010, Standardized World Income Inequality Database, Version 3.0.

Woo, Jaejoon, Elva Bova, Tidiane Kinda, and Y. Sophia Zhang, 2013, “Distributional Consequences of Fiscal Consolidation and the Role of Fiscal Policy: What Do the Data Say?” IMF Working Paper 13/195 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).