An Achilles’ Heel

Finance & Development, December 2013, Vol. 50, No. 4

Ravi Balakrishnan, Chad Steinberg, and Murtaza Syed

Inequality threatens Asia’s growth miracle

Over the past 25 years, Asia has grown faster than any other region of the world, leading many to label the coming years the “Asian Century.” With the region’s successful integration into the global marketplace and its large middle class increasingly coming to the fore, there are good reasons to think that the world economy will increasingly shift toward Asia in the coming decades.

However, Asia’s fortunes are threatened by a surge in inequality that has accompanied that quarter century of growth. Paradoxically, the same growth that reduced absolute poverty has created a widening wedge between haves and have-nots. This polarization has not only tarnished the region’s economic achievements but, left unaddressed, could leave Asia’s promise unfulfilled. As a consequence, policymakers throughout the region are looking for ways to arrest rising inequality and make growth more inclusive.

We look at what lies behind this worsening income distribution, why it matters, and what can be done to make Asian economic growth more inclusive.

Inclusive growth matters

Society should be interested in confronting inequality of income and wealth not just for ethical reasons but because it also has more tangible implications.

For a given growth rate, rising inequality typically means less poverty reduction. A growing body of research also shows that income disparities are associated with worse economic outcomes, including lower growth and greater volatility. At a fundamental level, income inequality is now widely thought to retard growth and development, for such reasons as limiting the accumulation of human capital in a society (see “More or Less,” in the September 2011 F&D). Recent work by Berg and Ostry (2011) also argues that unequal societies are less likely to sustain growth over a long period.

The most commonly used summary measure of income distribution is the Gini index. It varies from zero, which signifies complete equality because everyone has the same income, to 100, where there is total inequality because just one person has all of it. The lower the Gini index, then, the more equitably income is distributed among the various members of society. Relatively egalitarian societies like Sweden and Canada have Gini indices between 25 and 35, whereas most developed economies are clustered around 40. Many developing economies have Gini indices that are even higher.

Changes over time in a country’s Gini index can help demonstrate whether economic growth has been “inclusive”—that is, whether its benefits are increasingly shared by people at all income levels. A falling Gini index would suggest that the distribution of income is becoming more even.

More narrowly, we could home in on the most vulnerable—say, for example, the bottom 20 percent of the population—and see how much of the fruits of growth accrue to them. For example, we could ask how a 1 percent increase in national income affects them. If their incomes rise by at least 1 percent, growth can be said to be inclusive. But if the incomes of the poor rise by less, growth is not inclusive, because it leaves them relatively worse off.

Asia’s blemished record

Over the past two and a half decades, growth in most Asian economies has been higher, on average, than in other emerging markets. This growth has enabled significant reductions in absolute poverty—the number of people living in extreme poverty (on less than $1.25 a day) was almost halved, from more than 1.5 billion in 1990 to a little over 850 million in 2008. Despite this impressive overall record in poverty reduction, Asia is still home to two-thirds of the world’s poor, with China and India together accounting for almost half (see box).

Poverty and inequality in India and China

Poverty in China and India has been considerably reduced since the two largest countries began their economic takeoffs—three decades ago in China, two in India.

China’s poverty fell fastest during the early 1980s and mid-1990s, spurred by rural economic reforms, low initial inequality, and access to health care and education opportunities. In 1981, China was one of the world’s poorest nations with 84 percent of the population living on less than $1.25 a day—then the fifth-largest poverty incidence in the world. By 2008, 13 percent were in poverty, well below the developing economy average. India has also reduced poverty, although at a slower rate than China. In 1981, 60 percent of Indians lived on less than $1.25 a day, fewer than in China. By 2010, the share fell to 33 percent, but was two and a half times higher than in China.

However, inequality has increased in both countries. According to official estimates, China’s Gini (where zero represents the most equal income distribution and 100 the most unequal) increased from 37 in the mid-1990s to 49 in 2008. India’s Gini ticked up from 33 in 1993 to 37 in 2010, according to the Asian Development Bank (2012). There is also significant inequality based on gender, caste, and access to social services.

Between one-third and two-thirds of overall inequality in China and India reflects a widening of disparities between rural and urban areas, as well as between regions.

Moreover, inequality has increased across Asia. This is a new phenomenon for the region and contrasts starkly with its dramatic period of economic takeoff in the three decades before 1990. “Growth with equity” was the mantra during this period, as Japan and the Asian tigers were able to combine fast growth with relatively low—and in many cases falling—inequality. Asia’s recent dismal record on inequality is therefore a stunning turnaround.

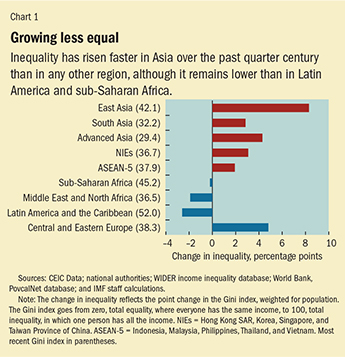

From an international perspective, inequality has risen faster in Asia over the past 25 years than in any other region (see Chart 1). The rise has been especially pronounced in China and east Asia, leaving Gini indices in many parts of the region between 35 and 45. That is still lower than in most sub-Saharan African and Latin American countries, which typically have Ginis in the range of 50. But countries in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa (as well as in the Middle East and North Africa) have on average bucked the global trend and reduced inequality in the past quarter century, shrinking the gap between them and Asia.

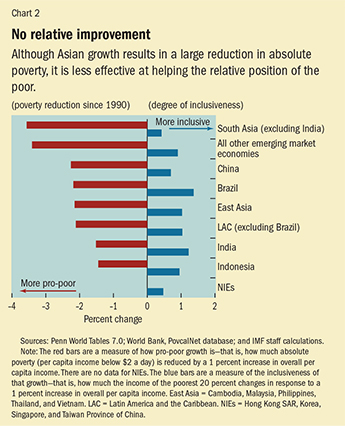

In particular, even as the purchasing power of Asia’s citizens has grown, the incomes of the bottom 20 percent have not risen as much as those of the rest of the population (see Chart 2). This is true both in relatively less developed economies, including China and much of south Asia, and in more advanced economies like Hong Kong SAR, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan Province of China. Asia’s experiences are a marked contrast to those of emerging market economies in other parts of the world, in particular in Latin America, where the incomes of the bottom 20 percent have risen by more than those of other sections of the population since 1990. So while Asia has undoubtedly led the globe in terms of rates of growth over the past 25 years, the nature of that growth has arguably been the least inclusive among all emerging regions.

Less inclusive

Rising inequality has been an almost global phenomenon over the past two and a half decades, with Gini indices generally ticking up across advanced and developing economies. Many analysts have attributed the rise at least in part to international forces beyond the control of any one country, such as globalization and technological change that favors skilled workers over unskilled ones.

The difference between the Asian experience and that of the rest of the world suggests that, in addition to global factors, there may be some specific features of Asia’s growth that have exacerbated the rise of inequality in the region. Addressing these factors—which our analysis suggests include fiscal policies, the structure of labor markets, and access to banking and other financial services—may hold the key to broadening the benefits of Asia’s growth, and hence sustaining it. In particular, increases in spending on education, years of schooling, and the labor share of income, as well as policies that expand access to financial services, significantly increase the inclusiveness of growth—that is, how much the income of the poorest rises when average incomes increase. Asia has fallen behind in many of these areas.

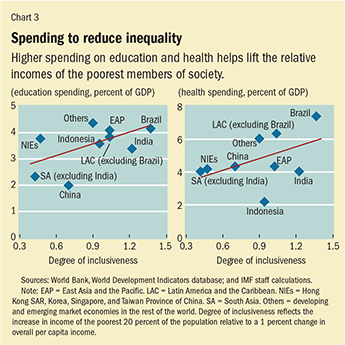

Public spending on the social sector is low, as a result of policy choices: The relatively low amount of public spending on health and education in Asia points to an important potential role for fiscal (tax and spending) policy in strengthening inclusiveness (see Chart 3). In advanced economies, taxes and transfer policies (such as those dealing with welfare and unemployment) have been estimated to reduce inequality on average by about one-quarter, based on Gini indices. In contrast, the redistributive impact of fiscal policy in Asia is severely restricted by lower tax-to-GDP ratios, which average half of those in advanced economies and are among the lowest in developing regions (Bastagli, Coady, and Gupta, 2012). The result is substantially lower levels of social spending. Greater reliance on less progressive tax and spending instruments also adds to inequality. In Asia, indirect taxes, such as those on consumption of goods and services, account for half of tax revenue, compared with less than one-third in advanced economies. Such taxes are paid disproportionately by the poor.

The labor share of income has shrunk considerably: In the past two decades across Asia there has been a significant decline in labor’s share of total income and an increase in the share that goes to capital, averaging about 15 percentage points, according to the Asian Development Bank (2012). This contributes to inequality because capital income tends to go to wealthier people, while poor people who work in the formal sector earn most of their income from wages. Technological change is part of the reason the capital share of national income has risen—and also part of the reason economic growth does not trigger as big an increase in demand for labor as it used to. But part of the changes in the capital-labor share of income may also be attributable to a deliberate bias toward industries that have a high capital-to-labor ratio in some parts of Asia. That tilt is reflected in their manufacturing and export-led policies, relatively low employment gains compared with their rapid growth rates, and the concentration of wealth in the hands of corporations rather than households. In addition, rising inequality is linked to the relatively weaker bargaining power of workers. Many workers in Asia toil in the mainly unregulated informal sector, which depresses wages. Moreover, even in the formal sector, lower-skilled workers have little to no bargaining power to raise relative wages.

Financial access is thin: Lack of access to finance is a major impediment in many parts of Asia, where more than half the population and a significant proportion of small and medium-sized enterprises have no connection to the formal financial system of banking, insurance, or securities. Research has demonstrated that financial development not only promotes economic growth but also helps apportion it more evenly. This is because lack of access to financial services and costs associated with transactions and contract enforcement take the biggest toll on poor people and small-scale entrepreneurs, who typically lack collateral, credit histories, and business connections. These deficiencies make it almost impossible for poor people to obtain financing, even if they have projects with high prospective returns. By fostering the development of financial markets and financial instruments—such as insurance products that make it easier for businesses and individuals to cope with shocks such as accidents or death—governments can both spur growth and help ensure that it is distributed more equitably.

Improving performance

So, on this basis, what types of policies might help Asian economies redress the recent period of less inclusive growth?

Fiscal policies: Asian governments must increase spending on education, health, and social protection, while maintaining fiscal prudence. Part of this could be achieved by raising tax-to-GDP ratios, particularly through a more progressive tax system or by broadening the base of direct taxes to boost the redistributive impact of fiscal policy. At the same time, targeted social expenditures aimed at vulnerable households could be increased. Conditional cash transfer programs—which require a specific socially desirable action from a household, such as increased school attendance or vaccinations—are on the rise in low-income emerging market economies. Brazil’s Bolsa Familia and Mexico’s Opportunidades are two of the largest such programs and are considered successful in raising the incomes of the poor.

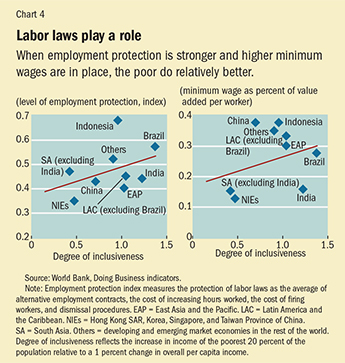

Labor market policies: Labor policies that enhance rural employment programs, increase the number of workers in the formal sector and reduce the size of the informal sector, remove impediments to labor mobility, and enhance worker training and skills could disproportionately help lower-skilled members of the labor force. In addition, the introduction of, or increases in, minimum wages has also been advocated in some countries to support the income of low-earning workers. For example, China’s announcement in February 2013 of a 35-point plan to tackle income inequality included a provision to raise minimum wages to at least 40 percent of average salaries across most regions by 2015. In general, we found that inclusiveness is positively associated with the degree of employment protection and minimum wage levels (see Chart 4).

Financial access: Recommendations based on international experience include expanding credit availability by promoting rural finance, extending microcredit (modest loans to small entrepreneurial operations), subsidizing lending to the poor, promoting credit information sharing, and developing venture capital markets for start-up businesses.

Follow through

If Asian countries pursue policy measures to broaden the benefits of growth, notably enhanced spending on health and primary and secondary education, stronger social safety nets, labor market interventions for lower-income workers, and financial inclusion, they could stem the tide of rising inequality.

Many of these policies have the added potential to reduce the bias toward capital and large corporate entities, broadening the benefits of growth for household incomes and consumption. In this way, they could also facilitate the needed change in Asia’s economic model from external to domestic demand that would prolong the region’s growth miracle and support global rebalancing. The stakes are high. Without action to redress inequality, Asia may find it difficult to sustain its rapid rates of growth and take a position at the center of the world economy in the years to come.

Ravi Balakrishnan is a Deputy Division Chief in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department; Chad Steinberg is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Strategy, Policy, and Review Department; and Murtaza Syed is the IMF’s Deputy Resident Representative in China.

This article is based on a 2013 IMF Working Paper, “The Elusive Quest for Inclusive Growth: Growth, Poverty, and Inequality in Asia.”

References

Asian Development Bank, 2012, “Outlook 2012: Confronting Rising Inequality in Asia” (Manila).

Bastagli, Francesca, David Coady, and Sanjeev Gupta, 2012, “Income Inequality and Fiscal Policy,” IMF Staff Discussion Note 12/08 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Berg, Andrew, and Jonathan Ostry, 2011, “Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” IMF Staff Discussion Note 11/08 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).