Only Fair

Finance & Development, March 2013, Vol. 50, No. 1

Nada al-Nashif and Zafiris Tzannatos

Social justice must be at the foundation of Arab economic reforms

Rahma Refaat, an Egyptian trade unionist from Cairo, has fought for social justice for decades.

“The first time I was arrested was in 1977 while protesting the bread price increase under President Anwar Sadat,” she says. “I was detained for six months.”

Refaat has been arrested countless times since, most recently during the January 25, 2011, protests that ushered in Egypt’s first democratically elected government. “We went to Tahrir to reject the humiliation of unemployment and oppression,” she says.

One outcome of the mass protests was the formation of the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions, breaking a six-decade state monopoly on the trade union movement. Scores more independent trade unions have since emerged.

But the revolution is still not over for Refaat and other activists: not until workers, employers, and civil society are involved in the policymaking process.

“Restrictions on unions must be lifted and social dialogue seriously pursued if we are to make Egypt a place for all Egyptians,” she says. “Politics and economics must go together—that’s unavoidable.”

Ordinary people

The Arab Spring came with little warning. The consensus had been that Arab governments were on the right track economically, if not politically—focusing on “economic reforms now, political ones later.” They were driving through long-awaited pro-market reforms—spearheaded by Tunisia and Egypt—and economies were growing relatively quickly. Some even spoke of an “Arab renaissance.”

But this description failed to capture what really mattered to most people: decent work, fair access to education and health care, support in old age, accountable government, and a say in how the country is run. It glossed over two decades of skewed economic policies, a widening social protection deficit, and the absence of institutionalized social dialogue between governments, workers, employers, and other segments of society. Instead, it focused on a narrow set of pro-market indicators such as the rate of privatization, trade openness, debt and inflation reduction, and foreign direct investment.

And when policymakers did look at the right indicators, they often misinterpreted them. For example, the focus on high youth unemployment missed the point that adult unemployment in the region was the highest in the world. Large numbers of young workers in fact constitute a window of demographic opportunity that, if properly used, can add bonus points to the economic growth rate. The quality of education in the region has indeed been low, but more relevant is the unsophisticated nature of production, which continued to demand only low levels of education and skill.

Amid declining social protection and in the absence of social dialogue, the living standards improved for some, but most Arab citizens could not reap the rewards of economic liberalization. Development failed to help the vast majority of the population and could not meet the aspirations of the rising number of increasingly educated Arabs. Arab citizens—young and old—suffered from a heightened sense of alienation and insecurity.

Not that fast

Arab governments emerged from the region’s “lost decade” of the 1980s—which witnessed a regional slowdown due to tumbling oil prices—with a slew of reforms to tackle stagnant, or even declining, per capita GDP, rising fiscal burdens, slow productivity growth, and low competitiveness. But these measures threatened the prevailing social contract that bound Arab rulers to their citizens: an unspoken trade-off in which citizens forfeited political freedom for public sector jobs, public services, and state handouts.

Governments across the region introduced economic reforms at various times and differing intensities beginning in the early 1990s. They achieved some objectives, such as reducing debt and inflation. Arab economies began to grow more quickly after the turn of the century, averaging 5 percent between 2000 and 2010. These growth rates, though unprecedented, were still lower than those of any other region except Latin America.

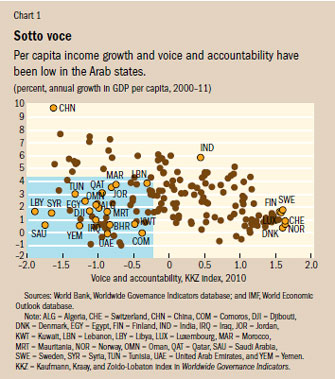

Even more disconcerting, the Arab region combined the lowest per capita income growth with the lowest rates of voice and accountability (see Chart 1). This meant that citizens had no say in policymaking. Governments remained oblivious to the social impact of economic reforms and ignored demands for accountable systems of governance.

Private sector woes

Increasing the role of the private sector was the centerpiece of economic reforms pursued by Arab states in the 1990s. Privatization, or more precisely denationalization, went hand in hand with opening up capital accounts and fiscal consolidation through expenditure cuts. The success of trade policies was measured in terms of “openness” instead of by how well they supported sustainable and inclusive growth. Contrary to expectations, the revitalized private sector didn’t produce sufficient gains to trickle down to middle-class and poor people.

Governments cut back on public investment on the assumption that it crowded out private investment. But total investment remained low in the Arab region. Moreover, it was directed to sectors that offered quick returns only to a few, such as finance, trade, and real estate. Foreign direct investment did increase but not as much as in other regions. In a globalizing world, what matters is not so much how fast one moves but how fast relative to others.

Successful privatization requires sound trade, financial, and foreign investment policies as well as transparency and sufficiently developed capital markets and accompanying institutional reforms. These have been largely absent in the Arab region. The rollback of the state was conducted without regard for the impact on the social sector of handing over public services to private operators.

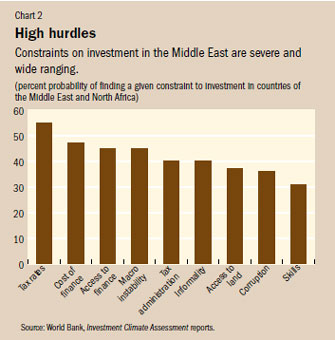

The private sector remained significantly constrained. Competition was subdued, and the region had the fewest—after Africa—competitors in local industry and the oldest median age of manufacturing firms (except in the high-income economies). It was not a low-skilled population that tied the hands of investors but taxes, corruption, and lack of access to finance and land (see Chart 2). Productivity in the region increased only slightly and remained below the world average.

Quantity versus quality

Arab unemployment has declined, especially among young people, since the 1990s thanks to job creation but also due to changing demographics. As the number of working-age people in the region stopped growing more than a decade ago, growth of the labor force began to decline, even though more women joined the labor force.

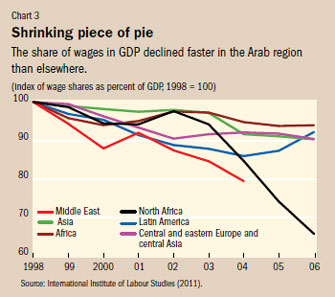

But jobs remained concentrated in low-productivity sectors such as agriculture and services and in the informal economy. As a result the Arab region was the only one where the reallocation of labor across sectors contributed negatively to productivity growth. The share of working poor declined over time but more slowly than in other regions, and the ratio of women’s share in low-quality jobs to men’s remained the highest in the world. What’s more, the share of wages in GDP declined faster than in the rest of the world (see Chart 3), suggesting that workers were getting an increasingly smaller slice of a growing pie.

The ratio of youths to adults has declined over time, a trend that began in North Africa in the 1980s and the Middle East in the mid-1990s. In the Gulf Cooperation Council countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—the youth-to-adult population ratio is already below the world average.

Rising school enrollment has helped reduce the share of young people in the labor force while increasing their employability. In fact, youth unemployment fell more than that of adult workers, in both the Middle East and North Africa. So the general explanation that the Arab Spring was the result of “too many unemployed youths” is not the full story. In fact, in the 1990s there were more young people and more of them were unemployed compared with adults than at the outset of the Arab Spring. Still, the high Arab unemployment rate is largely the result of very high unemployment among women, especially those who are young and educated.

While joblessness normally declines as household income increases, in the Arab region unemployment affects households from all income groups more or less uniformly. Educated job seekers have high unemployment rates and, when they are employed, the extra pay they receive for their education—known as the wage premium—is low. This can be partly attributed to the low quality of education or a mismatch between skills and the demands of the labor market. However, a more likely reason is the excess supply of adequately (in terms of local production requirements) educated job seekers following the impressive increase in education enrollment in the region, especially for women, since the 1960s. Finally, the region has one of the highest skilled emigration rates. Arab job seekers seem to be able to meet employment requirements in more sophisticated economies abroad but can find no decent work at home.

Skills constraints are among the least concerns of Arab employers (Chart 2). And the percentage of Arab firms offering training is the lowest in the world. This supports the view that the private sector is not competing through measures that would increase productivity but through extractive political methods.

Less help for the poor

By most measures, Arab poverty has not increased since the 1990s, and in some cases has declined, albeit more slowly than in the rest of the world. But the drop of the wage share in GDP (by 21 percent in the Middle East and 34 percent in North Africa; Chart 3) and perceptions of rising wealth inequality have reinforced a sense of exclusion created by elite privatization.

Social protection used to be administered through benefits linked to public sector employment, various subsidies, and access to expanding education and health services, albeit of low quality. This stretched public budgets, prompting economic reforms that reduced public services and the ability of the state to serve as employer of last resort.

Many of the reforms made sense. For example, universal subsidies for food or energy did not benefit the poor much, and benefits were earned predominantly through employment in the formal sector, especially the public sector. But expenditure cuts were too blunt—and were not cushioned by effective and sustainable social protection measures. The private sector stepped in selectively, and clubby business practices soon prevailed.

Pension reform was viewed less as a way to provide old-age security and more as a way to bolster capital markets. (Before 2008, the ills of unregulated financial markets had yet to be acknowledged). Formal sector employers continued to bear maternity benefit costs, which made hiring women less desirable. This ran contrary to the worldwide trend toward funding maternity benefits via social security so that all women are covered. And unemployment insurance was almost nonexistent before 2010—lowest in the world save in sub-Saharan Africa.

Toward a new social contract

In 2010, Arabs were more pessimistic about their prospects than at the start of the millennium. (See Figure 3.10 in ILO and UNDP, 2013) Despite the decline in unemployment, they harbored low expectations. Positive market indicators meant little to those struggling to make ends meet in low-quality, unrewarding jobs with little social protection and no access to social dialogue.

It was not the numbers of young people, their attitudes, or their education that prevented better labor market outcomes and faster output growth. Nor was it the increasing number of women in the labor force. Rather, skewed economic reforms failed to create a level playing field for the private sector, stymied productivity gains, cut access to social protection, and deprived most citizens of access to the benefits of growth. Though economic growth was not jobless, employment was unrewarding for many workers, which, coupled with a lack of social dialogue, prevented the collaborative development of inclusive growth and made citizens increasingly insecure and alienated.

In sum, pro-market reforms delivered some positive benefits and showed the potential of the private sector. But they failed to deliver the rates of economic growth and wealth creation that other regions have enjoyed in recent decades.

In the wake of the Arab Spring, Arab states must deliver more with less to assuage popular discontent and maintain social stability. This is why they need better targeted and more coherent policies developed in consultation with employers, workers, and civil society. We have seen the limitations of top-down politics.

In coming years, economic growth in the Arab region is expected to remain among the lowest worldwide, below even pre-2010 rates and too low to reduce unemployment. Future policies must avoid the mistakes of the past: applying untested theories, ignoring implementation constraints, and having social protection programs that lack clear economic and social criteria, with, for example, uncritical government spending cuts and failure to focus on the most needy.

What to do

Arabs need a new development model that is grounded in social justice: one that creates prosperity through equal opportunities, productivity gains, and decent work; expands social protection; and promotes social dialogue. Pro-market reforms are not synonymous with unregulated markets, and their social impact must be considered when deciding which reforms to implement and how. The role of governments in this respect is paramount. According to a World Bank report (Silva, Levin, and Morgandi, 2012), “at least eight in 10 adults in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia say their respective governments should bear the primary responsibility for helping the poor in their countries.”

Economic growth must be balanced and able to generate enough jobs and social services that allow men and women and their families to live in security and dignity. Employers and the self-employed need a level playing field to pursue legitimate profit-seeking activities, from micro and small-scale undertakings to full-scale investments, and move away from the kinds of investment with quick financial returns that benefited the establishment elite but excluded the majority of citizens. Future economic reforms should take full advantage of the private sector’s vast potential.

Economics first, politics later just won’t do for the Arab world anymore: politics and economics go hand in hand. Policymakers should ensure that the benefits of economic growth are shared fairly, by expanding social protection and making it more effective. Macroeconomic policies should be supported by well-designed active labor market programs and increased access to quality education and training for all income groups. And the region also urgently needs up-to-date and reliable information systems, better statistics tracking, and effective monitoring and evaluation of policies and programs.

Arab states must decisively cast off the remnants of an unraveling social and economic order to move toward inclusive economic growth. They must define a new social contract in a participatory way to meet the aspirations of millions of men and women—including Rahma Refaat—who refuse to settle for less. ■

Nada al-Nashif is Assistant Director General and Regional Director for the Arab States at the International Labour Organization. Zafiris Tzannatos is author of the joint International Labour Organization/United Nations Development Programme report “Rethinking Economic Growth: Towards Productive and Inclusive Arab Societies,” which is the basis for this article.

References

International Institute of Labour Studies, 2011, World of Work Report: Making Markets for Jobs (Geneva).

International Labour Organization (ILO) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2013, Rethinking Economic Growth: Towards Productive and Inclusive Arab Societies (Beirut).

Silva, Joana, Victoria Levin, and Matteo Morgandi, 2012, Inclusion and Resilience: The Way Forward for Social Safety Nets in The Middle East and North Africa (Washington: World Bank).

World Bank, Investment Climate Assessment reports (Washington, various years).