Every Which Way We Can

Finance & Development, December 2012, Vol. 49, No. 4

PDF version

![]() Forbes Philanthropy Summit

Forbes Philanthropy Summit

Philanthropy and private investment are increasingly important in the global fight against poverty

Global poverty reduction was once a battle financed by well-off countries with the support of international organizations such as the United Nations and the World Bank. But times are changing.

Philanthropic contributions by the likes of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and George Soros’s Open Society Foundation, social enterprises such as the Grameen Bank, and the increasing flow of investment funds to developing countries are now taking on a higher profile in the fight against poverty.

Developing economies are attracting more direct investment. But they still need official aid and money from private donors to help correct market failures and catalyze solutions for the poor (see box).

Spectrum of aid

Financial flows to developing economies for poverty reduction run the gamut from grants to private sector investment.

Grants, of course, are 100 percent subsidies to a government or nongovernmental organization to provide some service or transfer. In the middle of the spectrum are investments that aim to generate a social return above and beyond their private return—in the form of loans to governments or equity or loans to private firms. Such social net benefits may arise through positive externalities such as a smaller carbon footprint or a reduction in contagious diseases.

At the other end of the spectrum is private investment that generates strictly private returns, benefiting the investor, the firm, and the clients of the firm. Falling nowhere on the spectrum are investments that cause negative externalities, with a social return lower than private returns.

Giving trends

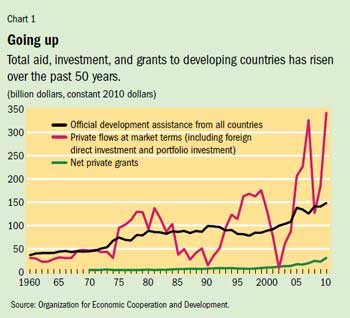

The total flow of financial resources to developing economies has been rising. The absolute level of global foreign aid (also known as official development assistance), private investment, and philanthropic grants to developing economies combined has increased since 1960 (see Chart 1). However, total bilateral and multilateral foreign aid has fallen as a percent of global GDP over the past half-century.

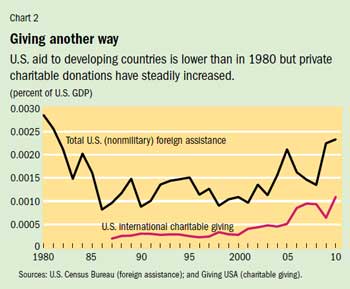

Consistent with global trends, foreign assistance from the United States, which is the largest single contributor worldwide in nominal terms (but not nearly the largest as a share of GDP) has fallen as a proportion of GDP over the past 50 years. Much of this decline was driven by a drop in assistance from 1980 to 2000—aid actually increased percentagewise from 2000 to 2010.

The U.S. government now contributes about 0.2 percent of its gross national income to foreign assistance; the Scandinavian countries Denmark, Norway, and Sweden all give close to 1 percent (United Nations Millennium Development Goals Indicators database). In absolute amounts, the United States contributed $31 billion in 2011, while France, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined—with two-thirds the population of the United States—contributed $58 billion. On a per capita basis, the United States contributed $99 in official aid, while these three European countries combined gave $280.

Some aid is direct budget support, whereas other aid takes on particular forms, such as technical assistance (e.g., Japan) or investment in infrastructure and industry (e.g., China). All these approaches ultimately aim to improve the quality of life in developing economies, while often also serving the donor country’s interests.

Shifts in public opinion

U.S. views on foreign aid can seem paradoxical. A 2010 survey showed that most people in the United States vastly overestimate how much federal spending goes to foreign aid, pegging it at 25 percent on average. The actual figure is less than 1 percent. Ironically, most Americans would like to “reduce” the foreign aid budget to 10 percent of overall spending—a sum that would actually represent a tenfold increase in aid (WorldPublicOpinion.org, 2010).

Attitudes toward aid are changing, however. In the United States, the share of people who would like to cut back on aid has declined steadily over the past 40 years, from a high of 79 percent in 1974 to a low of 60 percent in 2010, with a comparable increase in those who consider aid levels about right or even too low (General Social Survey, 2010). But even though they mistakenly believe that aid is quite high, Americans are on average more likely to say it should be higher still. They are also increasingly likely to commit their charitable dollars abroad: private donations to international causes began rising steadily as a percent of GDP beginning in the early 1980s (see Chart 2).

The growth of private philanthropy may be driven by Americans’ perception that nongovernmental assistance is more effective than government aid in promoting development (KFF, 2012). The accuracy of this perception is subject to debate, but new approaches, such as microcredit, led by nongovernmental organizations are certainly getting more media attention than reliable-yet-stodgy aid standbys like budget support.

Microcredit is in fact a particularly apt example of this phenomenon. A recipient of both private philanthropy and investment, it has risen to prominence on the back of tremendous fanfare, including a Nobel Peace Prize to the Grameen Bank and Muhammad Yunus in 2006. Web 2.0 services like Kiva also helped bring an already popular approach to a large retail audience, by promoting personal connectedness to aid recipients. Kiva allows donors to read the stories of individual clients and track their loan repayment, and it offers donors social recognition by featuring their stories and giving histories on its website. These are the Facebook generation’s equivalent of sponsor-a-child programs. New approaches, such as GiveDirectly, take the idea of direct connection to the next level and allow individual donations to flow directly to beneficiaries without an intermediary.

Thinking about sustainability

A major question for today’s philanthropists involves that alluring yet vaguely defined term “sustainability.” Charitable donations often play an important role in supporting the vulnerable in times of need when markets or governments can’t or won’t do so. But nonprofits’ dependence on donations makes them vulnerable to fluctuations in their funding, which can threaten their ability to achieve their goals—in other words, they’re not financially sustainable. Given the shortfalls of the nonprofit approach, some potential charitable donors have shifted from the grant-based end of the spectrum toward the middle—investments with social returns higher than private returns—and even off the spectrum, to investments with no social benefit beyond the private benefits.

The primary advantage for-profit firms have over nonprofits is that their revenues are tied directly to their products and services, providing financial feedback when the goods on offer are rejected by the market and ensuring financial sustainability when they’re in demand.

For donors concerned about financial sustainability, investment in developing countries offers the chance to better align revenues with beneficiaries’ outcomes and to create more financially sustainable organizations in the process, because demand from beneficiaries keeps successful programs afloat. Microcredit was one of the first major development industries to shift from a donation-dependent model to one that provides services at market rates to low-income clients.

In fact, it took some creativity to figure out how to lower market rates from moneylender levels to rates closer to those offered by commercial banks to wealthier individuals. For-profit microcredit banks have been criticized for valuing revenues over poverty alleviation, but often the product delivered to the client is more or less the same, and the few randomized trials to date do show more of an impact on poverty compared with the nonprofit model. Few programs have been tested rigorously, but the burden of proof is shifting, and proponents of the nonprofit model must show just how it is more effective than one driven by profit.

Of course, other factors may also influence investment levels. Donors likely turned their interest to financial sustainability because they were disillusioned by the ability of traditional aid to produce lasting change in developing economies. Although the impact of donor disenchantment is hard to gauge and perhaps plays a smaller role than other factors, it is likely no less real. Among the other influences on investment flows are technological innovation, trade barriers, international tax policy, U.S. monetary policy, and the policy environment in the recipient country.

Despite good reasons for enthusiasm about investment, a basic conundrum persists: many ideas indeed require and deserve a subsidy to make up for a market failure. And some level of redistribution makes good policy sense for reasons both positive (improved welfare of the poor helps society function better) and normative (ethics dictates some level of altruism and charity to those less fortunate). We cannot rely on investors to solve all the world’s problems.

An understanding of the structural shifts from aid and philanthropy to investment and a grasp of the appropriate levers for specific problems call for a good look at markets and when and why they work or fail. When market failures do exist, innovations can help solve them. Sometimes the answer lies in technology, such as cell phones or better bed nets to ward off disease-carrying mosquitoes, or in medicine. Sometimes it is about a business process, such as microcredit. When the problem is solvable without subsidy, market forces pull in investment.

The belief that the developing world’s problems are increasingly solvable without subsidies motivates many to focus on investment. Microcredit, for example, began as a nonprofit idea, blossomed, and is now dominated by for-profit investors seizing profit-making opportunities. This is akin to supporting basic growth theory: low-income countries should grow faster than their high-income counterparts because of expected higher marginal returns to capital, which is likely to attract investment.

Investment on the upswing

Investment in developing countries has been on a variable but generally upward path in the past half-century.

Such countries saw a large upswing during the global boom after World War II, an even larger drop during the political and economic turmoil of the 1980s, and a rebound from the 1990s to today (aside from temporary drops in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks in the United States and the 2008 financial crisis).

Two shifts in policy and the economic environment in developing economies deserve particular credit for higher investment: lower transaction costs and better information—concepts straight out of Economics 101. Market efficiency requires perfect information and zero transaction costs. The world may not work that way, but it is a good starting point for analysis and a way to figure out where things went wrong.

First, take “information,” which to economists has a particular meaning. Beyond mere data, information means the ability to complete transactions, to trust that a contract will be fulfilled, to ensure that all parties have symmetric information about the risks and rewards of a transaction. Improvements in institutional quality, in the spirit of Douglass North and, more recently, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson, are all about removing information asymmetries.

Improved information can lead to the creation and improvement of actual markets. For example, Robert Jensen’s seminal work on information and markets in Kerala, India, found that the introduction of cell phone towers allowed fishermen to call or text colleagues on shore about market prices before choosing a port. Access to this information led to a dramatic reduction in price differences across villages, higher incomes, more transactions, and less wasted fish (Jensen, 2007).

Transaction costs have fallen considerably over the past half-century. In the aftermath of the Cold War, as it became clear that state management of the economy was bad for growth, many developing economies adopted market-oriented economic policies with an eye toward removing information asymmetries for investors and reducing transaction costs.

To promote domestic investment, developing economies found it increasingly necessary to compete for international funds on the open market, which sparked additional rounds of reform to outdated tax codes and regulations for investor protection. Improved roads, less-restricted capital markets, lower trade barriers, faster and more reliable telecommunications, and of course the Internet have all helped lower the everyday cost of doing business. The result has been a steady reduction in the cost of starting a business. Data from the World Bank’s Doing Business index show a steady decline in the number of days it takes to start a business or register property in the average low-income country since 2005, when such data were first collected. And as institutions improve, investment flows.

Making an impact

What is investment’s impact on poverty reduction in the developing world? Where on the philanthropic spectrum does a given type of investment fall? And does it really matter?

“Impact investment” is a term many people use to describe investment in developing economies that carries considerable societal benefits, meaning that citizens in these countries are better off receiving “impact investment” funds than mere investment funds. But all investment should leave people better off than they were before, even in developing economies, as long as it doesn’t have negative consequences—“externalities” (and assuming away behavioral irrationalities that lead people to addictions, for example, to tobacco or alcohol, that they prefer not to have). Impact investment suggests causality, but rarely do the investors or firms produce rigorous research that convincingly demonstrates a program or investment produced a change in people’s lives that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

Economists agree that not all investments are equal. Investments that produce negative externalities—pollution, for example—may actually leave people worse off than before. And in some cases, an investment may merely shift wealth from one place to another. Investing in a firm that offers products already available in a community but whose advertising is more persuasive does not improve the lot of the poor; it simply shifts profits from one firm to another. But in the aggregate, any investment that improves competition and efficiency without causing negative externalities is likely to make people better off.

If impact investing is to be anything more than a marketing slogan, it must be more than an ordinary beneficial market transaction.

The question is, does the gain in societal welfare benefit third parties? In other words, are the social returns higher than the private returns? For example, a firm may come up with clean cookstove technology that uses less firewood than ordinary stoves. Customers save time and money when they need to collect less wood, other household members enjoy better indoor air quality, and the entire population benefits from reduced carbon dioxide emissions. Unfortunately, the rigorous evidence we have doesn’t support this picture perfect story for the cookstoves.

Similarly, the production of insecticide-treated bed nets doesn’t just protect customers from malaria, it also lowers the prevalence of the disease in the neighborhood. Investors who choose projects with the potential for both profits and positive externalities could claim to be more impact oriented than traditional investors.

Still, the belief that an investment will generate positive externalities doesn’t absolve firms from the ethical responsibility and pragmatic need to evaluate the actual benefits, just as charities must take a realistic look at the effects of their programs.

Impact investors can point to profit as an indication that their bed nets or cookstoves are in demand, but sales and participation rates alone do not prove that an investment has improved customers’ lives. After all, some of the most profitable products sold in the developing world are alcohol and tobacco (or local substitutes like khat), hardly known for their widespread societal benefits.

Microcredit is a case in point. For decades, microcredit practitioners made grand claims about poverty reduction based on assumptions rather than evidence and quantified their so-called success simply by tallying the number of participants. But stories appeared in the media that warned of overindebtedness, and people began to worry that microcredit was actually harming its participants. To make things more complicated, the negative stories suffered from as little analysis and data as the positive ones. Half a dozen recent randomized controlled trials have taught us that despite some positive impact from access to microcredit, it is not lifting millions out of poverty.

Philanthropist investors start out with a desire to generate broad social benefits, believing investment is the way to get there. But good cost-benefit analysis has a high price tag, and it is naïve to expect for-profit investors to pay for it if it doesn’t improve their bottom line. So who should pay? It needs to be a philanthropist who wants to measure whether the social returns exceed the private returns. This philanthropist could also be the investor. Not all investments (or aid projects for that matter) should be rigorously evaluated; that would be an unethically high allocation of resources to research. But we need more evidence than we have now.

Money flows will continue through foreign aid, private philanthropy, and investment. Each has its purpose, its merits, its drawbacks. But if our goal is to make a dent in societal problems, we owe it to our future selves and to future generations to make the time and effort to sort out what is good from what only sounds good. ■

Dean Karlan is Professor of Economics at Yale University and President and Founder of Innovations for Poverty Action.

References

General Social Survey, 2010 (May). www3.norc.org/GSS+Website

Jensen, Robert, 2007, “The Digital Provide: Information (Technology), Market Performance, and Welfare in the South Indian Fisheries Sector,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 122, No. 3, pp. 879–924.

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), 2012, “2012 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health.” www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/8304.cfm.

WorldPublicOpinion.org, 2010, “American Public Vastly Overestimates Amount of U.S. Foreign Aid.” www.worldpublicopinion.org/pipa/articles/brunitedstatescanadara/

670.php?lb=btda&pnt=670&nid=&id